For decades, writer and editor Christopher Priest has worked steadily for virtually every major comic book publisher. After a prolific career, Priest took some time away from the comic book medium to work on other professional endeavors. Since his return some years ago, he's added an acclaimed run on Deathstroke to kick off the DC Rebirth era and a bestselling relaunch of Vampirella to his long list of accomplishments.

In an exclusive interview with CBR, Priest reflects on his career, why he took a break from writing comic books and his determination to be recognized as a writer without qualifications.

CBR: Priest, you're the first Black writer-editor of mainstream comics in the United States, starting in 1979 with Crazy Magazine. How was it making that transition from intern to editor to writer at Marvel?

Christopher Priest: To be honest, it was mostly about hanging around. In those days, if you hung around Marvel long enough, somebody was bound to hire you. Unfortunately, the business has grown far too corporate to allow for that sort of thing anymore.

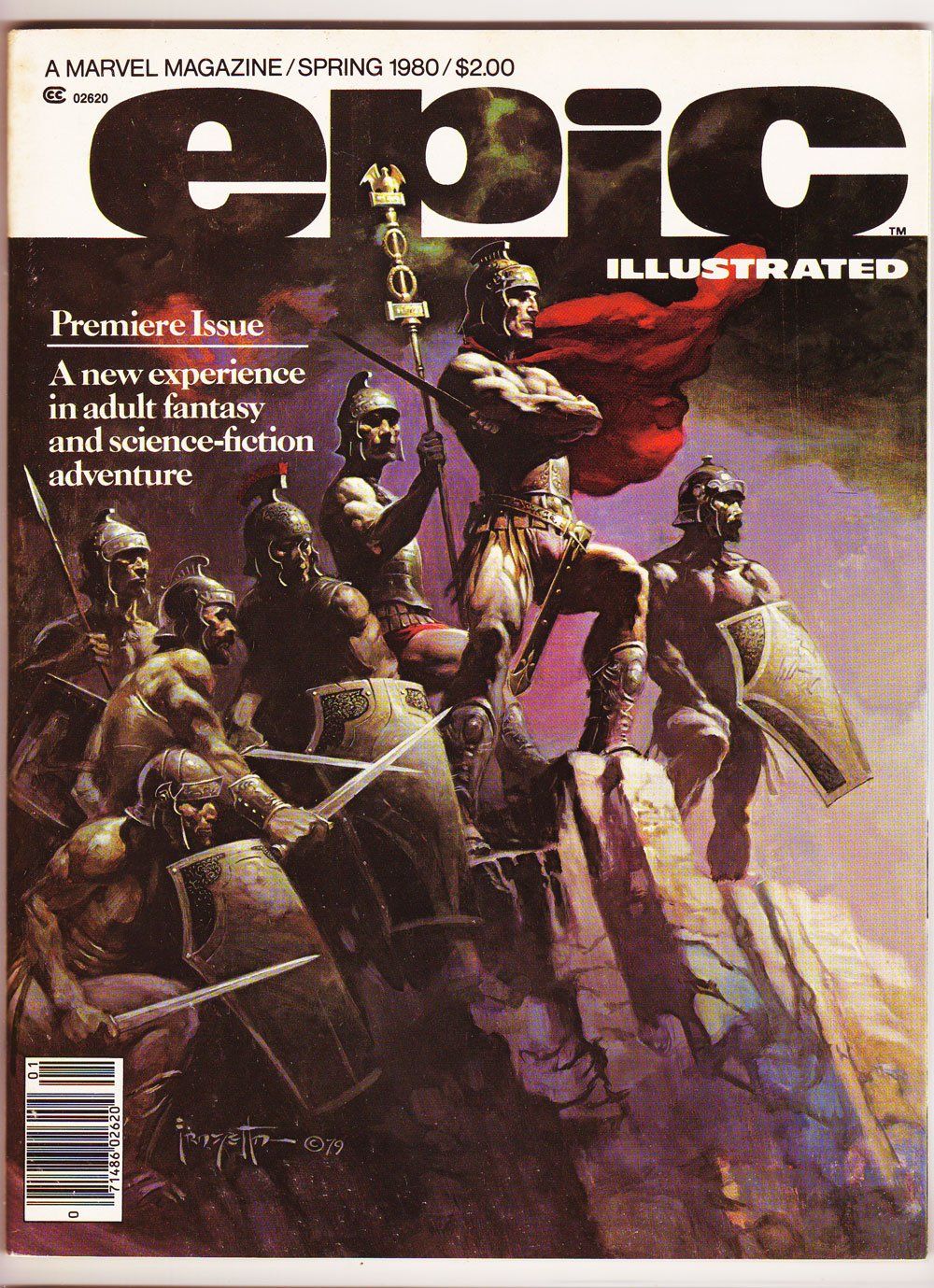

I had no sense of my being the first “Black” anything. I was just a kid who was ecstatic to have been selected by Marvel Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter to join the circus, working in an extremely kinetic creative environment and surrounded by some of the greatest artisans to ever work in the business. Shooter handed me over to EPIC Illustrated editors Rick Marschall and Ralph Macchio, who may well have been the funniest human beings I’d ever met.

I honestly don’t remember how or even why Crazy Magazine editor Paul Laiken hired me, but I transitioned from being an unpaid intern (starting in fall of 1978), to doing some freelance proofreading for editor Nelson Yomtov, to being an extremely poorly-paid gopher for Paul. Paul credited me as “assistant editor,” which I suppose I was, but I was mostly a kid trying to keep his office organized and trafficking art boards to and from Marvel’s production bullpen and ultimately out to the printer. Paul was eventually succeeded by Larry Hama and Shooter asked Larry to keep me on as a favor to him. Larry agreed, but insisted I be paid an actual salary... He felt I’d been interning under Paul for practically nothing.

As a result, I was offered a “real” job at Marvel with paperwork and everything. The money was a little better but still pitiful. I honestly didn’t care. Larry was amazing to work with. As both a writer and an artist I was blessed to learn from him, largely through the osmosis of watching Larry repeatedly sit with the talent and go over story and art.

After Crazy was cancelled, Larry was reassigned to head up the Robert E. Howard Conan franchise and we were both absorbed into the mainstream of Marvel editorial.

In striving to be recognized as a writer, without distinction of race, did that lead to a reluctance to write titles like Falcon, Power Man & Iron Fist, and Black Panther?

Priest: Well, you have to understand there was a huge gap between Power Man & Iron Fist and Black Panther. I was a kid without a portfolio when Jim Shooter marched me down the hall and forced me on the late Denny O’Neil, which Denny wasn’t happy about. In a situation like that, you just take the gig and keep your head down.

At no point did it even occur to me that my being Black played any role whatsoever in my landing the internship. It certainly played no role in Nelson or Paul’s hiring me, and I can absolutely guarantee my skin color played no role in Larry choosing to mentor me. I honestly didn’t notice any significance to my being a “first” anything and only learned about that later.

As for Power Man & Iron Fist, I’d like to believe Shooter forced me on Denny because it was an open book and a relatively low- profile place for me to get some real experience. Did Luke Cage’s ethnicity play some role? I don’t know.

Shooter had assigned me to Iron Man stories, Spider-Man stories, a Captain America graphic novel he made me rewrite 15 times. A Daredevil script which became Dan Jurgens’ first published Marvel work, a Thor GN I scripted over his plot. Ralph assigned me a Rampaging Hulk fill-in. A Doctor Strange. I was doing a lot; I was working those training wheels. I wrote a Falcon story which Shooter later evolved into a miniseries and I’m sure I must have written a Power Man & Iron Fist filler.

It just never occurred to me to make any connection between my skin color and landing my first ongoing comic book series.

And to be honest, if it had, I would not have cared.

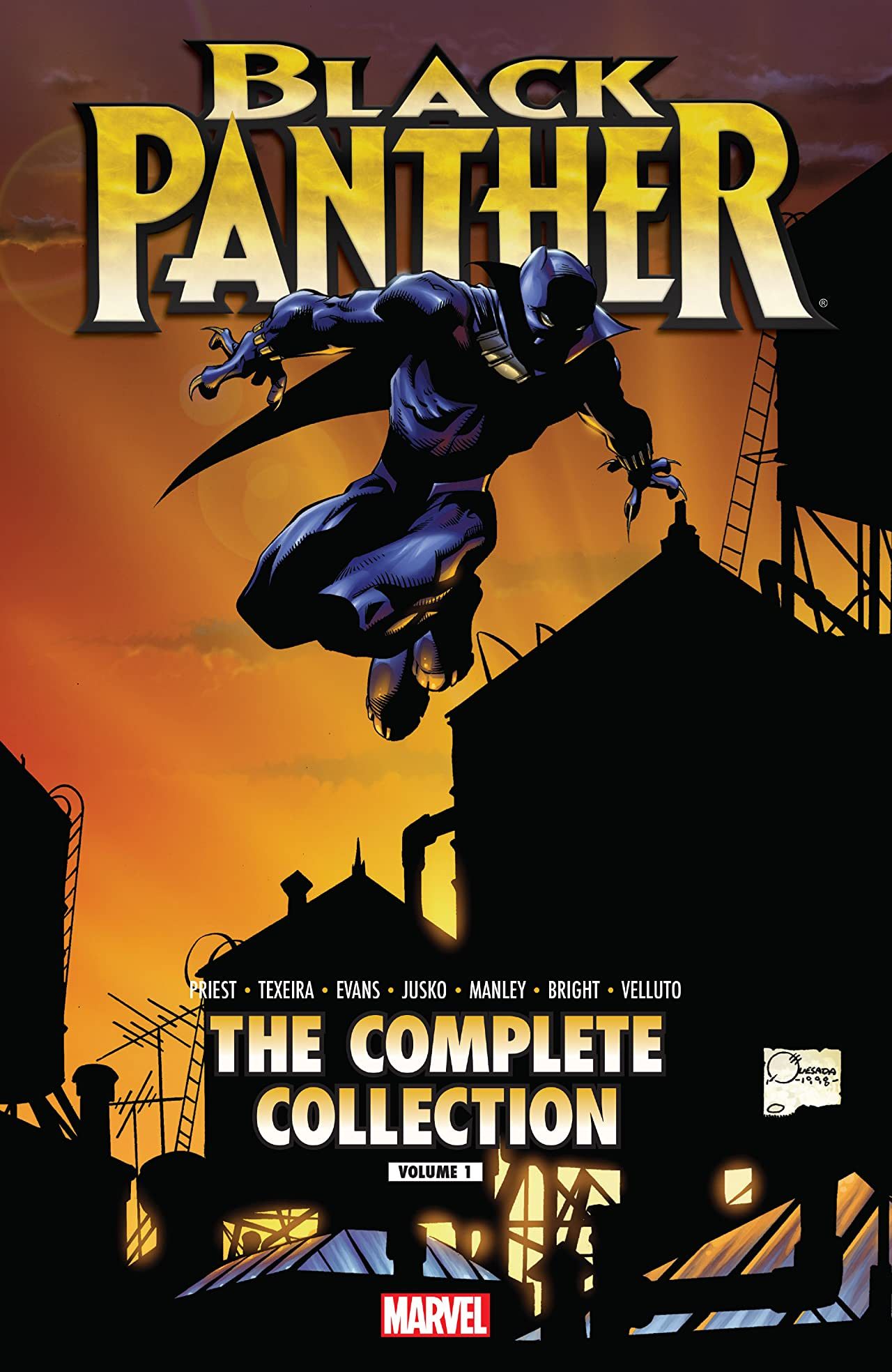

Now, by the time Marvel Knights launched Black Panther, I was an established pro and I initially turned the book down -- not so much because I was Black, but because I thought Panther was boring and I didn’t want to be locked into another low-selling book struggling to keep it alive. Superhero comics have traditionally been created by white males for white males, so writing a Black lead character has and still is an uphill push and I was really tired of working beneath the Sword of Damocles.

Mark Waid and former DC Group Editor Brian Augustyn, of all people, talked me into reconsidering, along with subsequent discussions with Marvel Knights chiefs Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti. Panther had languished for years as a generic character lost somewhere in the Avengers lineup. I assumed this was what Marvel wanted and that didn’t interest me.

But that was the last thing Quesada and Palmiotti wanted from any of their titles. Marvel Knights was, so far as I can recall, a point where Marvel began to pivot away from the traditional structure, which demanded that each writer maintain a consistent voice with those who had come before.

When I took over Power Man & Iron Fist, I was trying to keep the characters consistent to the wonderful and definitive run by Jo Duffy and Kerry Gammill. For the most part, those voices remained consistent, although I was chastised for -- as one Marvel editor put it -- “writing the worst Black dialogue,” because I no longer had Cage or Sam Wilson “speaking jive” all the time.

With Marvel Knights, Joe and Jimmy were handed Marvel’s castoffs to do with as they pleased, which meant we had a completely free hand to redefine norms. Now, when you’re used to being in a cage all your life and somebody comes along and opens the cage door, you’re still pretty hesitant. It took me some time to warm up to or even understand what Joe was saying to me. “What do you mean, I can do whatever I want?” That made no sense.

My reluctance toward the Panther project owed less to my being Black as it did to my not being Roy Thomas. With much respect and love to the venerable writer who trailblazed for all of us, I’m not that guy. Luckily, neither Joe nor Jimmy wanted me to be.

I did (and still do), however, want a shot at Daredevil, if only because Frank Miller is such an amazing and awesome writer, a guy who came into the biz and leapfrogged not only me but even celestials like Denny in terms of his sheer, raw talent. I won’t ever compare my writing to Frank’s, but boy did I want to get my hands on DD. Marvel, if you’re listening, I’m not dead yet.

You took a lengthy hiatus from comics. Why did you want to step away and what brought you back?

Priest: Well, Sam, it’s The Black Thing (TM). I am soooo sick of it. So tired of the pronoun. Maybe because, back in the Mad Men 1980s, Marvel was incredibly racist. But, let’s be fair: Marvel was also incredibly sexist. Incredibly Anti-Semitic. I’d never encountered anything like it: The sexist jokes, the Jewish jokes, yes, the racist jokes. At first, I was really kind of put off, until I realized no one was safe. Wait, that’s not true -- most staffers shied away from Polish jokes, because the boss was Polish.

One of my dearly beloved friends was the ancient wise man Morrie Kuramoto, who never let a day go by without lashing out at White America, celebrating Pearl Harbor day annually and so forth. Ralph Macchio utterly despised Heavyweight Champion Larry Holmes and hated Leon Sphinx even more, which earned Macchio a reputation as a racist. But, in his private moments, Ralph was exceptionally kind to me, spending hours teaching, shooting the breeze and -- yes -- lending me money.

Hama taught me I needed to have both patience and thick skin if I wanted to achieve anything in life. I could have taken offense and stormed out, or Shooter could have imposed strict Political Correctness guidelines. But Marvel was what it was in those days: Kill or be killed.

I hasten to add that, in the 40+ years I knew him, I never once heard Stan Lee make any racist, sexist, or homophobic jokes. I never saw him lose his temper or yell at anybody (though I have to imagine he must have at some point; I just never saw it). To my personal experience, Stan was exactly, to the letter, who and what you thought he was: A genuinely kind, creative genius. I was so honored to know him and thrilled, absolutely, every time I’d pass him in the hall and he’d pipe up, “Hiya, Jim!” Wow... Stan Lee knew my name... Of course, how many Black kids worked there?

But, yes, The Black Thing (TM) just became tiresome. I’ve mentioned this a lot in interviews, but long story short: Somehow, bizarrely, as a result of my writing Black Panther -- a comic book about the cultural awakening of a white man named Ross -- I stopped being a writer and somehow became a Black writer, offered only writing assignments for characters of color.

This snowballed into fan reaction to my Panther follow-up, The Crew, being -- as one fan put it -- “I’m so ghettoed out,” dismissing a really solid and innovative book. [It was] Marvel’s superhero version of The Wire, just because it featured minority characters. The Crew was cancelled before the first issue hit the stands, which angered me because Marvel VP Tom Brevoort, artist Joe Bennett and I had, collectively, opened up veins and bled all over that project. It was a labor of love and the bean counters outside of editorial just saw it as red ink on a P&L sheet, largely because both fans and retailers were openly hostile toward “ghetto” stuff, I suppose.

So I was ready to call it a night right there, but Tom called and said the magic words: Captain America. With Captain America & the Falcon, I felt welcomed back to the Marvel mainstream. Now I was a writer again, and not dismissed as a Black such and such. But when Marvel Knights ended their own Captain America run, Marvel chose to shrink the franchise to a single Cap book. I felt strongly that Bennett and I had paid our dues and earned a shot at the main title, but Marvel chose (for obvious marketing and sales reasons) to go with the stronger “name” value of Ed Brubaker.

Rather than cancel Bennett’s and my book, the decision was made to take Cap out of the book and relaunch it as The Falcon. I took it really hard. It felt like a demotion, like Marvel was saying I couldn’t cut it with their marquee characters anymore.

Meanwhile DC had offered me a trio of Green Lantern prose novels which I was waaaay late on, so I turned my attention toward those. Writing prose was so freeing and so much more fun than the constant struggle to grow a shrinking comic book audience, that I actually lost most of my fervor for the business altogether and instead turned my attention toward prose fiction and Christian ministry.

What made Deathstroke such an appealing title to make your return to DC Comics?

Priest: Oh, that’s easy: He wasn’t Black. After starting my Deathstroke run, I kept reading all of these posts about “Priest Is Back!” I never left. After building a career writing Green Lantern, Batman, Wonder Woman, Spider-Man and running that entire franchise, after selling a gazillion copies of Spider-Man vs. Wolverine and long runs on the Conan books and Power Man & Iron Fist -- somehow I became relegated to being a Black writer. Apparently, Black writers are less valued and ineligible to compete with “regular” writers. For years, I was offered only characters of color from Marvel and DC, which I politely declined.

And then DC Executive Editor Marie Javins called me.

Deathstroke, Marv Wolfman and George Perez’s scenery-chewing Teen Titans nemesis, had somehow become many DC writers’ go-to punching bag and -- just as often -- mindless brute steroid case. But, hey, he wasn’t Black, so I was in. DC’s Rebirth initiative provided wide latitude for me to reimagine the character as a deeply dysfunctional father primarily motivated by his love for his children. Slade Wilson is a man who loves and wants to be loved, but is capable of neither. He is, at the end of the day, self-sabotaging and emotionally stunted; House M.D. with a machine gun.

Editor Alex Antone and I were largely left alone to chart Deathstroke’s course, which provided amazing opportunities to explore this character and build out a rich new legacy for him, one I hope DC will continue and the DCEU won’t destroy, reverting him back to a mustache-twirling cipher. Thankfully, Esai Morales, limited as he is by the show’s budget, is really working the suit and wringing every possible bit of depth out of his Titans scene-stealing character -- and rumors continue to abound about a possible Deathstroke Joe Manganiello feature (maybe?).

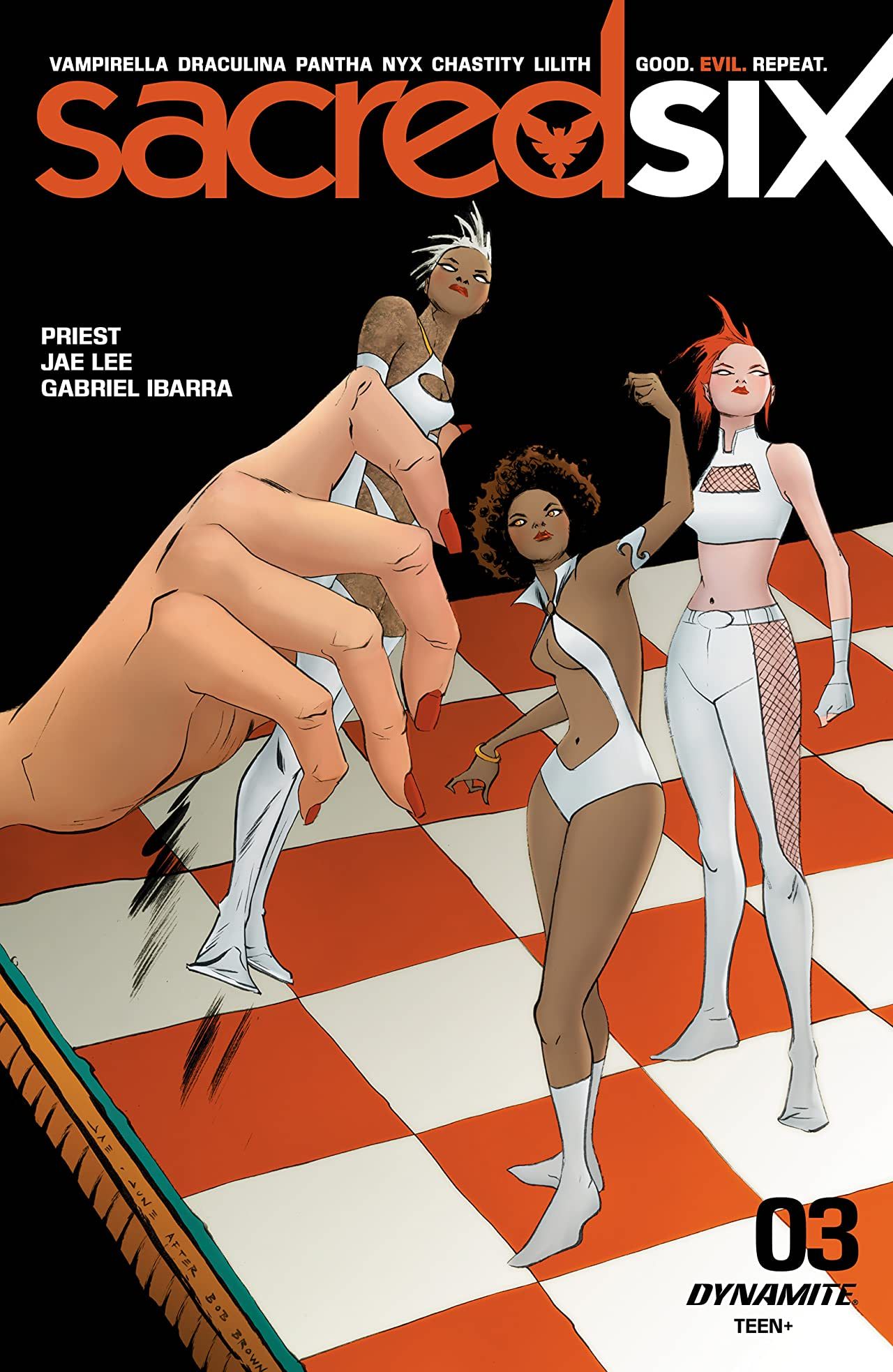

You've been helming Dynamite's relaunch of Vampirella and, the last time we spoke, you said you've developed a great deal of empathy for the character. I was wondering if you could elaborate on that and what keeps the character interesting to you as a storyteller.

Priest: Well, of course, it begins and ends with the costume. I get asked, a lot, how an ordained minister could take on a series about a half-naked, bloodthirsty space vampire. It’s a fair question. But, I have to say, Vampirella’s costume is not nearly as shocking or even titillating as it was during the Warren era of the 1970s. These days I see far more revealing outfits on the barely legal background dancers in rap videos.

I told Dynamite Entertainment Publisher Nick Barrucci the only way I could write about the devil is if I could also write about God, which I assumed would be a dealbreaker. To his credit, Barrucci bravely acquiesced so you will find a lot, lot, lot of high-minded theology threading through this series: Existential questions of existence and creation. The moral center of the book is a male witch.

I remember a local pastor spotting me in a bar with some friends and giving me some rhythm later on about appearances and such. What he didn’t know, because he just walked past without stopping by the bar to greet me, was I and another believer were witnessing to this man who was going through a terrible time. We prayed there at the bar and I went to my car and got my good bible, my good bonded leather one with the soft binding so you can shake it at sinners like Jimmy Swaggart used to, and gave it to this man because he was a trucker just passing through, so I didn’t have time to go to the church and pick up a generic pew bible.

While I expect my evangelical brothers and sisters to condemn me to hell, because condemning people is what Church Folk are good at, I gently remind them that after His crucifixion Jesus is alleged to have preached to lost souls in Hell. A preacher preaches; you preach wherever a door opens [1 Corinthians 16:9].

Beyond that, art is art. Christians should not be forced to choose between their art (for example, pop music) and their beliefs. Vampirella does not define me, but I strive to create truthful observations of the human condition, unfiltered by my personal moral convictions.

Vampirella is like any other young woman in the big city. YouTube is chock full of these scary videos made by terribly young women launching out for the Big City with their hopes in the backseat and barely a month’s rent in their wallet. Forget Vampirella, those videos are the real horror: These precious young lives driving off to be fleeced and taken advantage of because the Big City is often an extremely cruel place.

Like everyone else, Vampirella wants what we all want: Acceptance, purpose. We want to love and to be loved. But, much like myself and many reading this, Vampirella is often denied those things simply because she is different. People presume things -- typically, negative things -- about her based on a cursory observation. She’s half naked; she drinks blood.

To me, she’s Casper, the deceased child wandering the Earth trying to make friends, only to scare them all away. She is easy to identify with. Thankfully, Barrucci, much like Quesada, has invited me into this world not to perpetrate an existing voice but to bring a unique evolution for the character, which encouraged me to launch out and explore.

I was wondering if you could speak to your experiences helping launch Milestone Media in 1993.

Priest: Wow, that’s a really big subject and I’m already 3,000 words in! Okay, let’s try this: You’ve heard the name Pete Best, original drummer for The Beatles? That’s me. I was part of the original partnership that developed the Dakota Universe and which later became known as Milestone Media. There’s a whole essay about this (and a lot of other things) on my website.

Is there any message you'd like to leave readers with during this time?

Priest: I realize my race has some relevance and importance in terms of encouraging future generations or, perhaps, shaming past ones, but I’m a human being. If I ripped my face off and John Smith White Guy ripped his face off, we’d look exactly the same: A bloody skull. Which makes this whole skin color thing astonishingly ignorant and stupid.

I look forward to the future, where we’ll all be bald and wearing reflective chrome jumpsuits, as Jerry Seinfeld described it. No offense intended, but I’m just exhausted answering race-related comics industry questions because, for me, it marginalizes so much of who I am and relegates me to a footnote. I’ve done a lot of good work. I’ve written a bunch of bad stories. I’ve helped launch a lot of careers and I’ve pissed off a lot of people (sorry). I came, I edited, I wrote, I loved. I am so much more than Black.