One of the key figures in modern comics is Chris Claremont. After the epic period of creativity that came out of the Golden and Silver Ages of comics, Claremont emerged as one of the preeminent storytellers in the Bronze Age. Claremont became a defining voice for modern superhero comics through his work on Uncanny X-Men and related titles, and although he didn't create the concept, he's the one who made it work--and made it flourish.

After doing a number of peripheral X-Men titles and other work in recent years, the writer stepped away from mutants--and comics at large. The final issues of X-Men Forever 2, New Mutants Forever and Chaos War: X-Men came out in early 2011 but were written by the New York-based writer in late 2010. For over a year now, Chris Claremont hasn't written a single page of comics script.

Although he's turned his focus to prose novels for the time being, Claremont remains in tune with developments in the comic industry that he worked in for so many years. In a far-ranging discussion with the London-born writer, we talked about the modern comics movie blockbuster, digital comics, the seduction of work-for-hire and news about his own creator-owned comics.

Chris Arrant: 2011 was a different kind of year for you and for fans of your work, Chris. What are you planning for 2012?

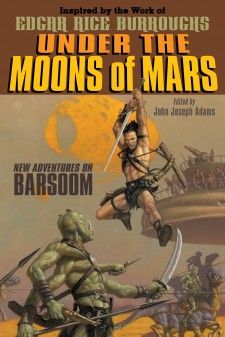

Chris Claremont: Well, I’ve got a prose novel making the rounds to potential publishers, and a short story in Simon & Schuster’s Under The Moons of Mars: New Adventures of Barsoom anthology. I’m working on another novel that’ll hopefully be in a position to start sharing with publishers soon as well. This year’s the first time I’ve been able to do things that are all totally mine and all totally different.

Chris Arrant: Are these sequels to your Willow novels or perhaps the First Flight novels you did a few years back?

Chris Claremont: No, the Willow books are George Lucas’; the fate of that is up to him. And these aren’t connected to First Flight either. They’re all in different genres with different emphasis. The novel making the rounds now is a young-adult adventure, and the novel on my desk right now that I’m stitching together for my agent is much more of a mystery/suspense.

Chris Arrant: Even if you’re working outside of comics currently, you’ll always be associated with the medium. Given that you have a little distance from the day-to-day of working in comics, what are your thoughts about the comics industry and medium as a whole?

Chris Claremont: This is the first time in 40 years that I haven’t written a line of comics work in a year. That is part of what’s enabled me to do a lot more prose. It’s a totally different experience, and I’m getting used to being on the outside looking in and on the inside looking out.

As far as the industry is concerned, it’s clearly in a period of evolution. I think that DC’s revamping of their entire line conceptually has brought them a measure of strong success this year. I think Marvel is taking whatever steps it feels appropriate to respond.

Over in the X-Men line of titles, I see that there seems to be a structural redefinition of the canon that will substantially change readers’ relationships with the characters, in the sense that some characters who you felt were on one side of the line in behavior now seem to be turning into anti-heroes, as I understand. Wolverine’s become head of the school, and Cyclops has been positioned as a Magneto equivalent, a good soul taking a violently pro-active stance toward mutants’ perceived antagonists in the world. It’ll be interesting to see how that all relates to the readership.

Last I looked at the Fantastic Four, Johnny Storm was dead, so that puts that title in a period of evolution as well. I don’t know if that death will be one that’s permitted to last, especially if Fox generates a new film arc. But meanwhile, it opens up a whole plethora of possibilities for writers to try new wrinkles on the classic theme of the book.

The Avengers, I assume, will be more increasingly geared toward presentation in line with the upcoming film. I know that we all have incredibly high hopes for that to work, so we’ll just have to wait and see. I mentioned Fox earlier, and I don’t know if they’ve firmed up plans to continue with the First Class concept and if they’ll attempt to reintroduce the Fantastic Four.

Chris Arrant: Since we’re talking about movies, what do you think of the showdown that’s shaping up this year for movies? You have The Avengers, Amazing Spider-Man, The Dark Knight Rises and a few others all coming out close to one another.

Chris Claremont: Summer is going to get real crazy--much like it’s been recently with the holiday releases. There have been so many huge films opening that I’d argue who’s had time to watch them all. None of the December films are anything approaching mega-hits, which I think is partly because public schools like the ones here in New York City didn’t have a long Christmas break. So it’ll be interesting to see if the winter films make any money.

Getting back to your question, the summer film season is going to be a very “no holds barred,” “whack-a-mole” kind of situation. Again it’s interesting to look at it from the outside to see how the pieces get shuffled around and who comes out on top. You’ve got to assume The Dark Knight Rises is going to have the most momentum because Christopher Nolan’s last Batman movie made $1 billion and change, and Inception was a financial and critical triumph. This new one is a wrap-up of his trilogy and from the trailer alone--that football scene alone--it’s bound to intrigue the living daylights out of people. Thinking about that more in depth, looking at the structure of the trailer, I’m wondering if Bane could perhaps be what was left of Ra’s al Ghul in disguise.

Chris Arrant: That’s an interesting theory.

Chris Claremont: At the same token, Sony’s got a huge stake in making Amazing Spider-Man successful. Raimi’s trilogy was successful in their own right, and if this one doesn’t hit that level right off the top then they’re in trouble. And Marvel and Disney have a huge stake riding on The Avengers. All of these films have a lot riding on them. The irony is that there’s so much emphasis and raw money on the films that the source material, the comics, are a little bitty piece off to the side now. From the studios’ point-of-view, the comics aren’t as relevant as we like to think, which is intriguing and sad. You then have to wonder how the publishers are going to respond, or anticipate whatever happens in a way that’ll make the comics reach out to a wider, more enthusiastic and long-lasting audience.

The next level in the equation is the evolution of the marketplace itself. The three-dimensional comic store is not the only way of presenting comics to an audience, with every comic having the potential digital download product to your iPad or whatever. That opens a whole new level of possibilities for a wider, global audience instantaneously. Not to mention the money publishers could save on print runs as they lean more digitally in distribution. Imagine if one of the primary publishing houses started doing in-house translations of new work for foreign-language audiences. Imagine if, as Avengers vs. X-Men was being lettered, there was also an in-house translation team doing the same for Europe, South America and other places for simultaneous day-and-date global release. That would in turn open up a whole new vast spectrum of audience, much like movies did.

If you go back 15 years, the domestic movie box office was the primary and near-exclusive revenue source for studios. Now the domestic American box office, strong or weak, is a minor fraction of the global take. Remember me mentioning how the last Batman movie did $1 billion and some change? $400 million of that came from U.S. movie-goers, but the other $700 came from outside our borders. Look at Avatar: the foreign ticket sales were over twice the domestic returns. The mind boggles at those kinds of numbers, but that’s what you get when you effectively reach out to a global audience. If that kind of thing came to comics, it would undoubtedly change how people perceive the mainstream industry.

If you look at that kind of thing coming in the horizon, you then think, “Do you write books exclusively for English-language audiences, or do you try to find ways to appeal elsewhere?” That was, in my own mind, the base subtext of GeNext when I was doing it a few years ago. One of the reasons all the stories in the second arc were set in India was because I wanted to see if it was possible to reach out and perhaps appeal to the sub-continental audience. If we’d gone to a third series, that would have been set in China; an intentionally global concept if it went forward as an ongoing.

Think about it: you have a whole host of X-Men locked up in North America; enough already, let’s see if we can entice a more international clientele. In a way, this kind of thinking goes back to where we started: Stan Lee, Roy Thomas, Dave Cockrum, Len Wein in 1975’s Giant-Size X-Men--with the intentionally international team. It worked then, and it could work now.

Again, following the paradigm of cinema, in the old days releasing movies overseas was an afterthought but now it’s integral to the movie business. In some films it wouldn’t be surprising to see the United States envisioned as a significant but not primary dominant marketplace, and treated accordingly. But in comics, that’s for the governing minds at each of the companies and corporations to find out for themselves. Whether or not any of it comes to pass or whether or not the management teams at Marvel and DC are all that interested, or capable, of doing it is open for debate. I’m not interested or qualified enough to make that call.

Chris Arrant: You’ve put a lot of thought on the shape of the comics medium even though you haven’t written comics in a year. Do you feel any excitement for anything currently on the comics shelf?

Chris Claremont: Embarrassing as it sounds, I don’t. I’m not that interested. My basic response is that I’m not the intended audience anymore. But I have a certain vision for certain characters, and Marvel, for example, is taking their books in a direction that is not simpatico with that vision, so for me it’s easier to focus on other things that are definitely more enjoyable. I enjoy the memories, and enjoy the work that’s been done when I come across it, and then I move on to other things.

Chris Arrant: Earlier this year you donated your writing archive to Columbia University to act as the basis for a comics research center. How’d that come about?

Chris Claremont: They called. [laughs]

It was incredibly flattering and a significant honor that they would be so taken with the work I’ve done that they would wish to archive it in this way. It’s over 40 years of material, and there isn’t a writer around who’s been working for a lifetime that doesn’t have a room/basement/house full of crap, [laughs], that their spouse has been passionately suggesting to get rid of. Not because they don’t like the stuff, but because it’s clutter. For me, the longer it stays in the basement the more risk there will be that it’ll be lost. I’ve had enough basement floods in my life that it would be a shame to lose all my articles. I’ve lost most of my comics before, and manuscripts as well, so I’m glad as much survived as it has.

The collection really bridges the distance between when we worked on typewriters to the digital age. So while I may have 25 years worth of computer files or print-outs, I also have a dozen years of typewritten original manuscripts and drafts. It’s the original pages where Jean became Phoenix, and even John Byrne and my early work on Iron Fist leading into Uncanny X-Men. All of that stuff was done on a Selectrix typewriter. There may be bad Xeroxes of some of this stuff out there, but this archive are the originals. There are handwritten notes for ideas that worked, and ideas that didn’t work. Sketches of novels, musings, you name it, it’s in there. It’ll be interesting to see what it involves into once they fully access and collate the material. Hopefully it’ll prove of value to students and scholars in the future.

Chris Arrant: Since you mentioned rarities, it gives me an opening to talk about some unfinished projects you’ve done, namely the plans for the creator-owned Huntsman series. The characters debuted in an arc of Jim Lee’s Wildcats, but nothing ever came of that. Will that material be in the archive?

Chris Claremont: I still have all the raw material for the Huntsman, but it’s staying with me because it’s still an active concept. There’s a lot of stuff not going to the archive because it’s still being worked on. Although Image/Wildstorm couldn’t find a way to make it fit with their plans, it’s just a matter of finding a new venue to present it. Whether that’s in comics, prose or a screenplay, I don’t know.

Since you’ve showed interest in Huntsman, I’ll tell you something: the irony of that project was that it was planned to go into its own series shortly after its debut in Wildcats, but the artist involved had other ideas and wanted to do a series of his own. We couldn’t find anybody to take his place, and things moved out of sync and the opportunity evaporated. It happens all the time; everybody pitches scads of ideas that don’t make it. The first challenge that every writer or creator of material faces is getting through the crowd so that the person you’re trying to sell it to hears the pitch and is able to respond to it. If you get a positive response, then you have to produce.

I have two comics projects that I started in Europe, one science fiction and one fantasy. The fantasy series, titled Wanderers, got one issue published, a second issue fully complete and a third one plotted out before the artist left to work for Marvel. That’s no fault of the artist, but the book was published as a dual-publishing arrangement between a French and Italian publisher that came to blows. I think the French publisher was hoping for better sales of the first volume, and lost interest afterwards. But now because of that, I’ve got a hundred pages of story sitting on my desk. The other series, the science fiction one, went to the publisher and an artist drew 20 odd pages before the company collapsed. The other publishers I’ve shown it to were interested, but said that either the artist or the story wasn’t quite right for them. Again, there are many cases of concepts that look golden to creators but hit speed bumps along the way and never make it to fruition. That’s the business.

Chris Arrant: But from the way you’re talking, we might eventually see them released in one form or another.

Chris Claremont: Right, but it also provides reasoning from a writer’s perspective why many prefer prose over comics. At least with prose, the only person you have to worry about is oneself. You don’t have to worry about the artist. I’ve got concepts galore, but in the modern formula for getting comics made you have to find an artist, produce samples, then pitch and sell it. The pressures of the marketplace make it extremely challenging for those pieces to come together in an effective way. Finding an artist to take the time and risk, and paradoxically for a writer to take the time and risk. Teaming together, producing the work, flogging the work, finding the right marketplace in terms of a publisher and the right marketplace in terms of readers.

But if it was easy, everybody would do it. That’s why work-for-hire is so seductive; you don’t have to worry about any of that. You just do your job, stay friends with the editors, cash your check and move on.

Chris Arrant: Since we’re on the subject of creator-owned work, I have to ask; is any of your previous work like Sovereign Seven or Black Dragon up for re-release?

Chris Claremont: Funny you mention it, but Black Dragon is coming back via Titan Publishing this year, along with Marada, The She-Wolf.

Speaking more broadly and coming back around to our discussion of digital publishing, that is an avenue I’m increasingly looking towards for more. I’ve got a lot of material that is now out of print; the First Flight prose novel trilogy is going to be released digitally. With the collapse of Borders, people need a place to sell books and digital looks to be just that.

The one problem there, the potential disadvantage of digital versus 3-D is the ability to browse. When wandering through a bookstore, you look for a good cover or an interesting genre to see what catches your eye. It’s tangible. There’s much, much less of that to me onscreen with digital books. For digital, you go to a specific place and search for a specific book and can’t see what’s proverbially standing right beside it. My wife had a professor at NYU whose way of doing research when beginning a project carried on with this thinking. He’d find a basic reference book and then go to the library and look it up in the Dewey Decimal System down to the decimal point and see what surrounded it on the shelves. He’d wander up and down the stacks all afternoon to see what caught his eye. If anything caught his eye, he’d read the first page and if it looked promising he’d keep going. Every so often he’d get a serendipitous moment that would spark him off in a whole new, different direction.

The problem with digital bookstores is that it’s an A-to-B link. You want a book by a certain author, you get the book. Readers have no idea what’s right next door; no way of exploring and being taken by surprise and discovery. So how that affects the industry--and the audience--will be an interesting thing to watch over the next few years and decades as we get used to it.

On one hand the convenience of digital distribution is unparalleled, but on the other hand there’s no opportunity to discover… and bluntly, that’s a problem comics have right now. With everything increasingly geared toward central flagship concepts and mass crossovers, you have stores being asked to buy all the Avengers-oriented titles, for example, then books that don’t have those connections, whether it’s at Marvel, DC or outside, that have a rougher time. Before you even think about getting readers invested in a title, you have to figure out how to get the retailers invested. If retailers are put in a position where they have to throw 80 to 90% of their available budget to get all of the mainstream titles from DC and Marvel and then dependable peripheral books from Dark Horse and others, the one little itty bitty book with no link to anything might get just get an order of one or two copies, optimistically. With another round of event comics coming down the pike this year, it’s a far more challenging and brutal environment for new material, unexpected material, non-canonical material. And on the flipside unfortunately, publishers have less incentive to push what’s considered non-canonical work because those non-canonical work diminishes canonical work which they need to sell.

Chris Arrant: It makes you think that if Watchmen debuted today if it would’ve been able to capture audiences like it did when it was originally released.

Chris Claremont: DC would still publish Watchmen; they’d sell it to the comic stories and maybe sell 30,000, and that would be it. Back in the '80s, it took a mainstream publisher coming to DC and saying, “You guys are idiots! Let us have the book, we’ll market it and show you how it’s done.” The next thing you know, Alan and Dave are all over the bestseller lists. Even if the movie was self-destructive, the book still endures.

Comics publishers are used to looking in a very, very narrow focused prism. It’s like when I started writing X-Men. Our “meat and potatoes” money was made of newsstand sales, while anything that came through the Direct Market was considered gravy. In everything we did in those early years up through the '80s, everything we sold to the Direct Market was pure profit because we’d already paid for the printing with our newsstand sales; we were just cranking out money.

But on the flipside, when DC made the decision to go exclusively to the Direct Market, it made life much easier because they’d have the orders in before they set the print runs and would just print a marginal amount of extra copies. That way you didn’t have to worry about 200,000 excess copies unsold by the newsstand, for example. But the negative to being exclusively aimed at the Direct Market is that you’re selling to a committed audience and not bringing any new kids in the door. When Marvel followed DC’s route for the Direct Market, they were going for guaranteed profit and minimal risk, but newsstands had a much bigger potential for sales and induction of new readers.

Once local comic shops began going away in the '90s, it put a lot of those readers out because not many people are willing to drive 40 or 50 miles for comics; they’ll simply move on to other things. The fiscal decision in the '90s to maximize profit at the expense of investment was like cutting our own throats. But on the other hand, the guys making those decisions are now billionaires.