Welcome to the CBR SUNDAY CONVERSATION, a weekly feature where we speak in-depth -- and at-length -- with some of the most interesting members of the comic book community. These discussions run the gamut in terms of topics, from current projects to classic stories, talking trends, tastes and wherever else the conversations lead.

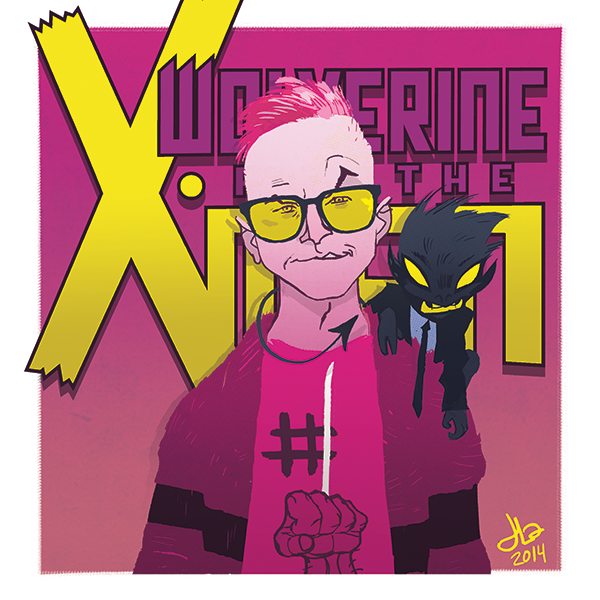

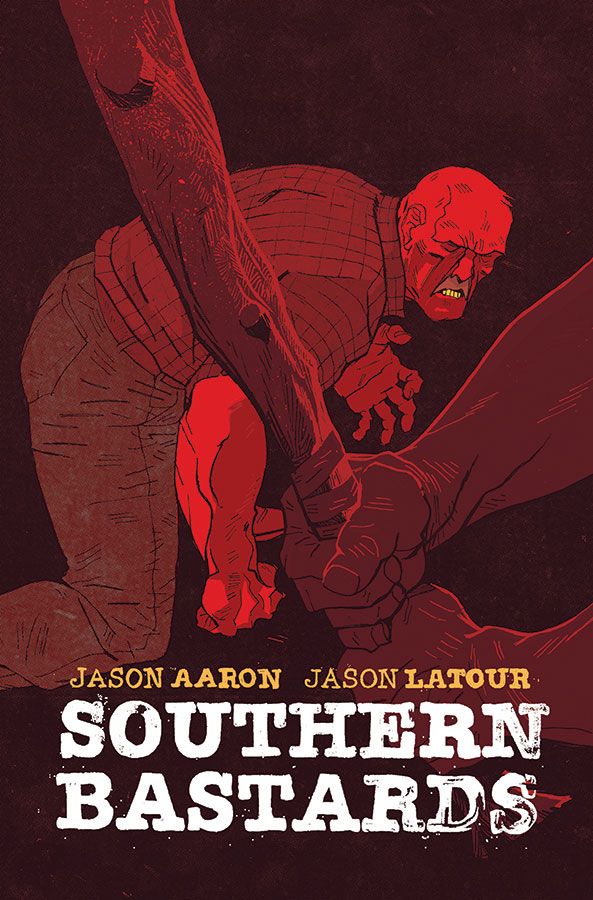

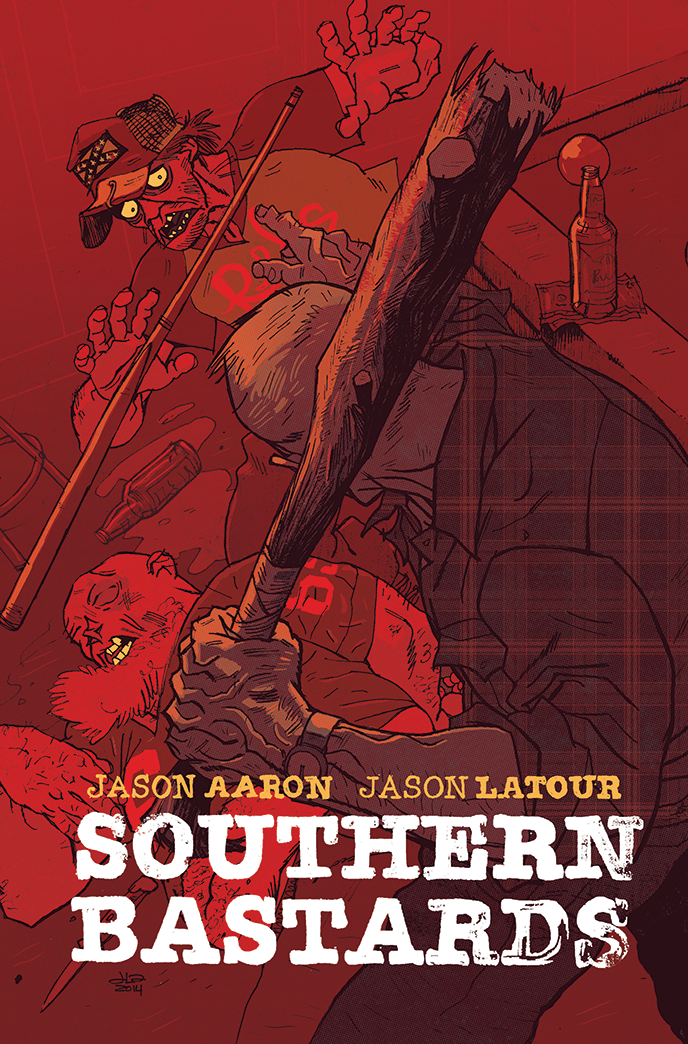

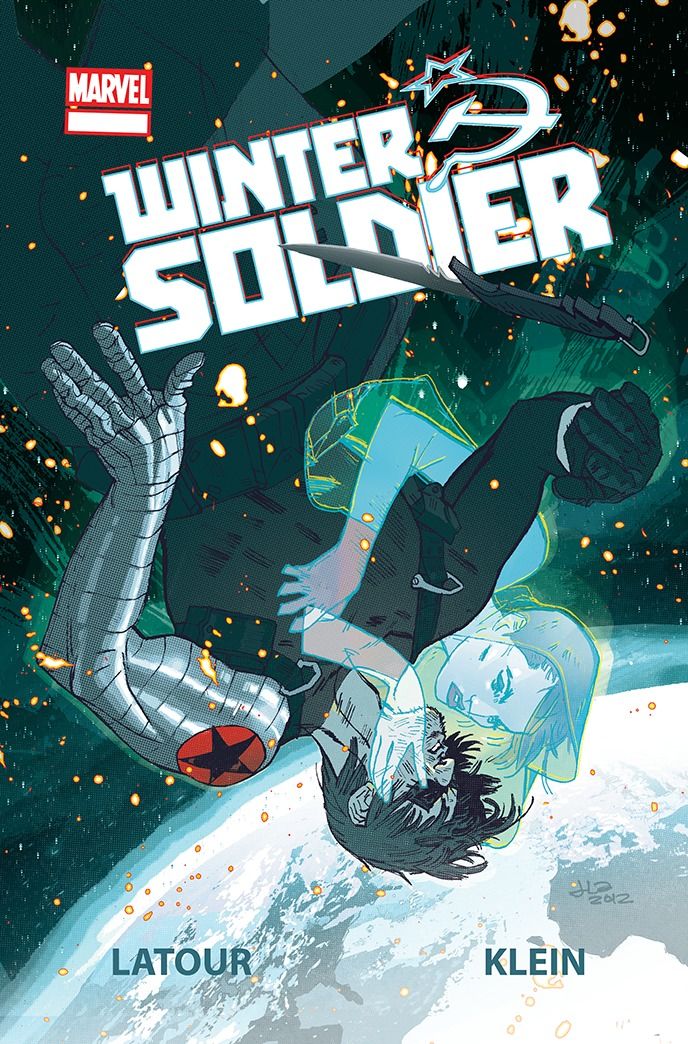

Writer/artist Jason Latour grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina, and though he spent time away from the south, the desire to reconcile his complex relationship with the region's culture drew him back to his hometown as an adult. In addition to scripting Marvel Comics' "Wolverine and the X-Men," he currently draws upon childhood memory and current frustration in his art for "Southern Bastards," a collaboration with Jason Aaron for Image Comics. Latour wrote of his relationship with southern culture in an essay at the back of the series' first issue.

CBR News reached out to learn more about Latour's roots, what he misses, and how it haunts his art.

CBR News: I'm sure I'm not alone in that I was quite taken with those personal essays you and Jason Aaron wrote in the back of "Southern Bastards" #1 as to your complicated relationship with the south. I thought, if you'd be comfortable revisiting that, we might expand on it.

Jason Latour: Yeah, sure. I don't know how much I can add very succinctly. I can try.

Where do you come from?

I was born and raised in Charlotte, North Carolina, which is where I happen to live again now. I moved here about four years ago. It was a very different place then than it is now though. A lot of the things that bother me about the south that I got at in my essay are things that I'm a little wistful for now because they seem to be disappearing. For better or worse, you know?

In the way the region is portrayed in fiction -- there are those negative portrayals, but there's also this concept of a mystical south.

Oh yeah.

X-POSITION: Latour Channels the Phoenix in "Wolverine and the X-Men"

You mentioned being wistful, and I think a lot of people who haven't spent much time in the Carolinas might conjure up an image of Mayberry. There's something a bit fantastical about that sleepy, romanticized town. Does that come close to the place you're nostalgic for?

Mayberry is pretty near and dear to my heart, being that that's all from North Carolina. I have an almost familial connection to Andy Griffith, even though I've never really watched a ton of it. When I do catch it, it takes me to a place. I always imagine those episodes going to much darker places though. [Laughs] The plots are all like dark noirs waiting to happen. All it takes is Barney firing his gun for once.

Like Andy forgets to confiscate that one bullet out of Barney's breast pocket.

The whole show would come down around Andy's ears.

And Otis is a pretty dark idea, having this town drunk with such a routine that he locks himself up in the pokey every other night.

Well, Andy Griffith is kind of a dark dude. If you've ever seen "A Face in the Crowd."

For sure.

I guess he got so method there that he decided never to take another role like that. It took him to some pretty scary places. In the better episodes of "The Andy Griffith Show" there's a dark underbelly to that stuff. My relationship with this place is further compounded by two other things. One, my mother's from rural North Carolina. I'd spend a lot of weekends on a farm with nothing to do but draw and read. Then I'd come home and live most of the rest of the week in what was considered a big city. Much like in "Southern Bastards" when the people are like, "Oh, you live in Birmingham? That's a big town." It was that kind of thing. Also, my dad's parents moved down here from Detroit in the '50s, so I have a whole side of my family from Michigan.

What do you miss? What makes you wistful?

What do I miss? You know, a lot of it's just nostalgia. It's not like it was exactly better, but I think there was sort of a Mom 'n Pop-ness to the way things used to be. Especially this town now. There's so much money here. Whatever sense of history that we had is rapidly being repurposed or torn away. Things like restaurants or little landmarks. Places that people used to own and run by themselves. It's not a problem that's specific to just the south, but I think you see it more and more in this region because there's such an influx of people moving in. It's a banking center now. You've got a microcosm of what's going on in the rest of the country. It's hard to put it into words. It's one of the big reasons I was attracted to doing "Southern Bastards," just trying to find a way to articulate these things. They say a picture's worth a thousand words. On some level it's my attempt to do that.

Have you encountered those people you're drawing?

Oh yeah. [Laughs] I either grew up with them, or -- there's a lot of cousins and aunts and uncles there in those faces and those behaviors. I also played high school football, so the further we get into it, there's a lot more of that experience.

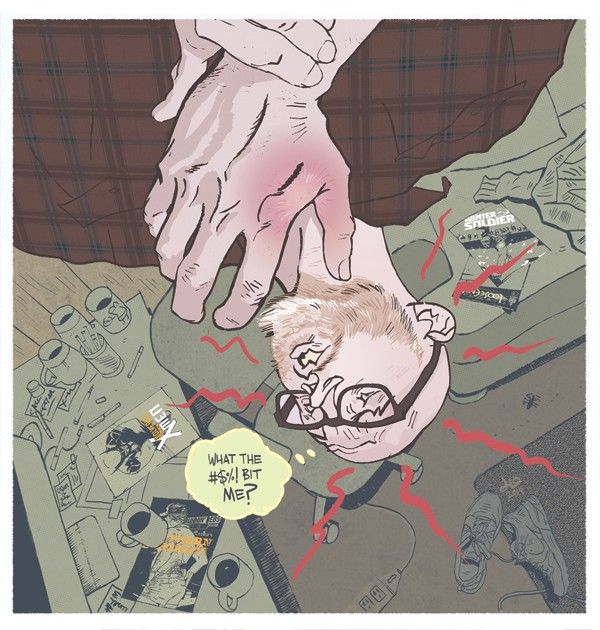

With issue #2 I was really impressed with that two-page panel looking at the lineup on the field. It's not an angle I think I'd ever seen in a comic before. It's not a recreation of a trading card or a "Sports Illustrated" spread. It's more intimate than that. You're drawing on personal experience.

I am, and a love for the sport, too. For all its warts. I still watch NFL pretty religiously, but it's pretty much the only football I can watch anymore. College sports, the setup, just bothers me, morally.

How so?

I think, in a lot of ways, they really use these kids. More than that, it's some of the things we're getting at in the book, the misplaced pride, the way people use it as an excuse to hate their neighbors rather than actually enjoy the game. [Laughs]. Here, it was more basketball. But I also went to an SEC college, so I've seen a lot of it. I've been in a lot of arguments myself where it was apparent that we weren't really arguing about the teams. We were arguing about our differences. Or somebody's trying to pridefully -- they just need something to make themselves feel better. It's not really about the game. At least with the pro sports, with all the warts and problems have with it being about money, at least these are guys that have to get up and play every day. They're already rich. A lot of them are really still playing for -- maybe not purer reasons, but personal reasons. But as to the way I portrayed it in the book, it used to upset me as a kid to see artists glaze over those scenes. But on the other side of it, there's not a lot of sports fiction that's engaging as a narrative. It's just hard to do something that doesn't fall into biopic territory.

A lot of times when you see it in comics, and this goes for most team sports, it just looks like a foosball table. It's all regimented, players all in lines, and it feels more like a manual than something that captures the experience of a live game. You picked some great angles.

Thanks. It was just about finding the right vehicle for that. I think one thing that helps is that there's kind of a cartoon gag element to all of it because they're still high school kids. It doesn't have to be the epitome of physical perfection or football at its highest level.

And it's not a huge stadium with a ton of audience and architecture to get bogged down in. It's an appropriate scale to the high school level and to the area.

Which lends itself to the intimacy of the comics page.

Every collaboration comes about differently, so I was curious whether or not this was all a happy accident. Was Aaron aware of your background, and was that part of the reason this came together?

No, it wasn't an accident. I've known Jason since before the beard. [Laughs]

[Laughs]

RELATED: Aaron Serves Up a 'Morally Ambiguous' Tale in "Southern Bastards"

That should be his band. No, I knew him before he even did "Scalped," when he was still working on "The Other Side." I knew some of the guys that lived in Kansas City, near him. People were always saying we'd get along. I don't know if they based that on the fact that we liked football or were both southern and liked comics, but they were right. We started hanging out and talking more. I think the first time we hung out we talked about "Apocalypse Now" for three hours. I knew right away that even though I had aspirations to write and draw my own stuff, I knew I wanted to do something longer form with this guy at some point. And then it just happened that his career took off and that helped put us in a place where we could do something like this and people would pay attention to it. I was getting more and more work in different capacities, and it just felt like if we didn't do something now, we'd probably never get to it, ya know? We'd been discussing doing a crime fiction thing for a long time because we both have a deep love for that, but we wanted it to be personal if it was gonna be an indie book. We'd been circling this idea of doing a Dixie mafia style book for a long time, and Jason had this idea for a football coach crime boss, that I liked. There's a lot of levels to that, especially if you understand the culture down here. If you take it the wrong way it could seem a little broad, but I think knowing it as intimately as we do, we can add nuance, or use it as a window into some things. And after years of kicking it around, there was this confluence of events -- our careers being in the right place, Image having this resurgence and interest in a book from us. Especially him. We'd sit beside each other at shows and over the course of a weekend we came up with this whole story. Something pretty funny that happened in my personal life sort of inspired the whole thing with the tree being hit by lightning.

Did you pull a mystical club from out of the scorched remains of a tree, or--?

[Laughs] I'm probably going to write this story in the back of an issue, but teasing it isn't such a bad idea.

Cool. You mentioned that affinity for southern noir. Are there any stories in particular that you think get it right?

I don't want to bash "Justified" because I do think there's a lot of good stuff in the show. But some of the shortcomings of that series were actually an inspiration for us. Some of the Hollywoodness of it that we wanted to avoid. I'm a big fan of [Elmore] Leonard's original short story ["Fire in the Hole"]. If I remember correctly, or at least it was my impression of it at the time, Raylan was a much older man. That was always in the discussion. Jason and I always thought, from the moment it was introduced, that it should be an older man. That was always in the discussion. So there are all these things that were a tangential influence. But in therms of a genre, I think it's more like literature than genre-oriented fiction. We both like Faulkner. I haven't read a ton of Faulkner, but I've read the big stuff.

You have a favorite?

Yeah, I go back to "The Sound and the Fury" a lot. I know that's a pretty easy answer, but there are so many crazy ideas in that.

It's an easy answer for a reason though.

Yeah. That book is way ahead of its time, just in terms of like, perception of human consciousness on some level. All the broken time stuff. The way that's linked to a very human regret or misplaced sense of duty. And again, that book has mysticism in it to a degree. I guess that's the answer for that. Cormac McCarthy, too. Far and away my favorite author.

Right on.

We talked a lot about that. Like the tree with the lightning. There's a scene in, I think, "Blood Meridian" where the kid sees a tree hit by lightning. That's always been in my head. It's hard to put my finger on anything as direct influences. A lot of music though. Some of the best crime-tinged fiction, at least southern crime, is from Drive by Truckers. Even bands like Handsome Family. A lot of country western stuff is not quite crime fiction, but essentially the same in an emotive sense. Outlaw country is steeped in that stuff. I think that's fitting, because the deep south is really a base for a lot of where American music comes from.

RELATED: Lowe, Hine & Latour Takes Readers to the "Edge of Spider-Verse"

You said you went away from the south for a while and then came back. What brought you back.

Oh, a lot of things. [Laughs] One, I just felt it was time. I'd been in New York for a while and I really loved New York, but I really wanted to make a go of comics, and at the time I didn't really have the means to do anything in New York but work. And that's pretty much the M.O. of comics anyway. You're going to have to work around the clock. It'd just become untenable for the goals I had. I could've stayed and had a good time and scraped by, or I could've hunkered down somewhere and tried to really make a run of doing comics. The second part of that decision was that I always had a really love/hate relationship with where I'm from. I felt like, as an adult, if I was gonna be happy to some degree -- however you can quantify happiness -- I felt like I was going to have to reckon with where I came from. That's not to say -- I have a very loving and close family -- it's the context that I grew up in. I needed to come back and at least come to peace with it.

Were there any one or two things in particular that you needed to resolve?

Yeah. It's hard to articulate. I think it's very difficult to be an artist in America, in general. I think particularly in the area I came from. It was just a very rare thing to have aspirations to want to do it. That's a thing that permeates across the board. There's a sense that -- southerners, right or wrong, feel like they're right about their view of the world. If you have a different view of the world, it's very hard to get people to understand that even if they want to. It's engrained. That was largely it. There's a lot of great people here, and there's a lot of great people who have that view point, too. What bothered me the most about growing up here is that I'm a lot like those people. I needed to reckon with that, to put myself to the test and see if I was capable of being more open-minded and more forgiving and more easy-going about things without losing my sense of self and my ambition.

Did you get a hard time about wanting to be an artist?

No, I just felt misunderstood. It wasn't like I got beat up for it. It's particularly hard to explain to people. It's hard in society in general because art is not easily quantifiable in western culture. You can't mark it on a ledger and show what it's worth. For most people, art is entertainment. That's a larger, systemic problem. That doesn't have anything to do with individuals so much as it does the lack of education. Here, it's probably as bad as it is anywhere. Maybe it's changing a little around here, but growing up, there was no art funding. I was lucky I just had a comic book shop. That's really where and why I became an artist. I had access to comic books. Without that in my life, maybe I would've found another path, but I don't know. Maybe I wouldn't have. For whatever reason, I think a lot of artists are incapable of dealing with their emotions, and art is how they hopefully learn how to do that, teach themselves how to deal. I think that's why dudes pick up guitars. When you live in an environment where people don't think that's a normal thing to do, it's kind of a pressure cooker. I feel like it's made me a better artist in the long run, but there are probably a lot of those feelings that I would trade for being -- maybe if I had the option, I'm not sure that I would take the same path. I've tried other things and failed miserably. Art was always just -- I don't know if I would call it a calling, but definitely the only outlet I felt was really available, or really real.

Stay tuned to CBR News for more on Jason Latour's upcoming projects and follow him on Twitter at @jasonlatour.