Welcome to the CBR SUNDAY CONVERSATION, a weekly feature where we speak in-depth -- and at-length -- with some of the most interesting members of the comic book community. These discussions run the gamut in terms of topics, from current projects to classic stories, talking trends, tastes and wherever else the conversations lead.

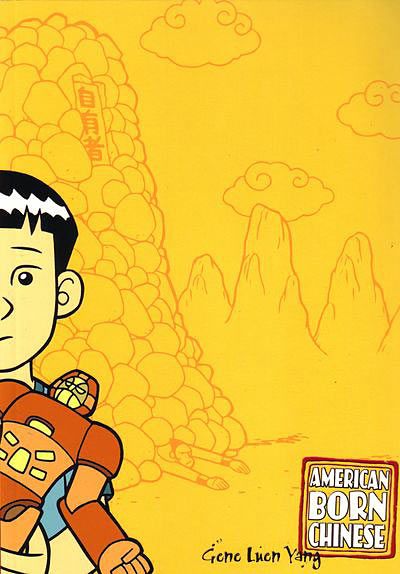

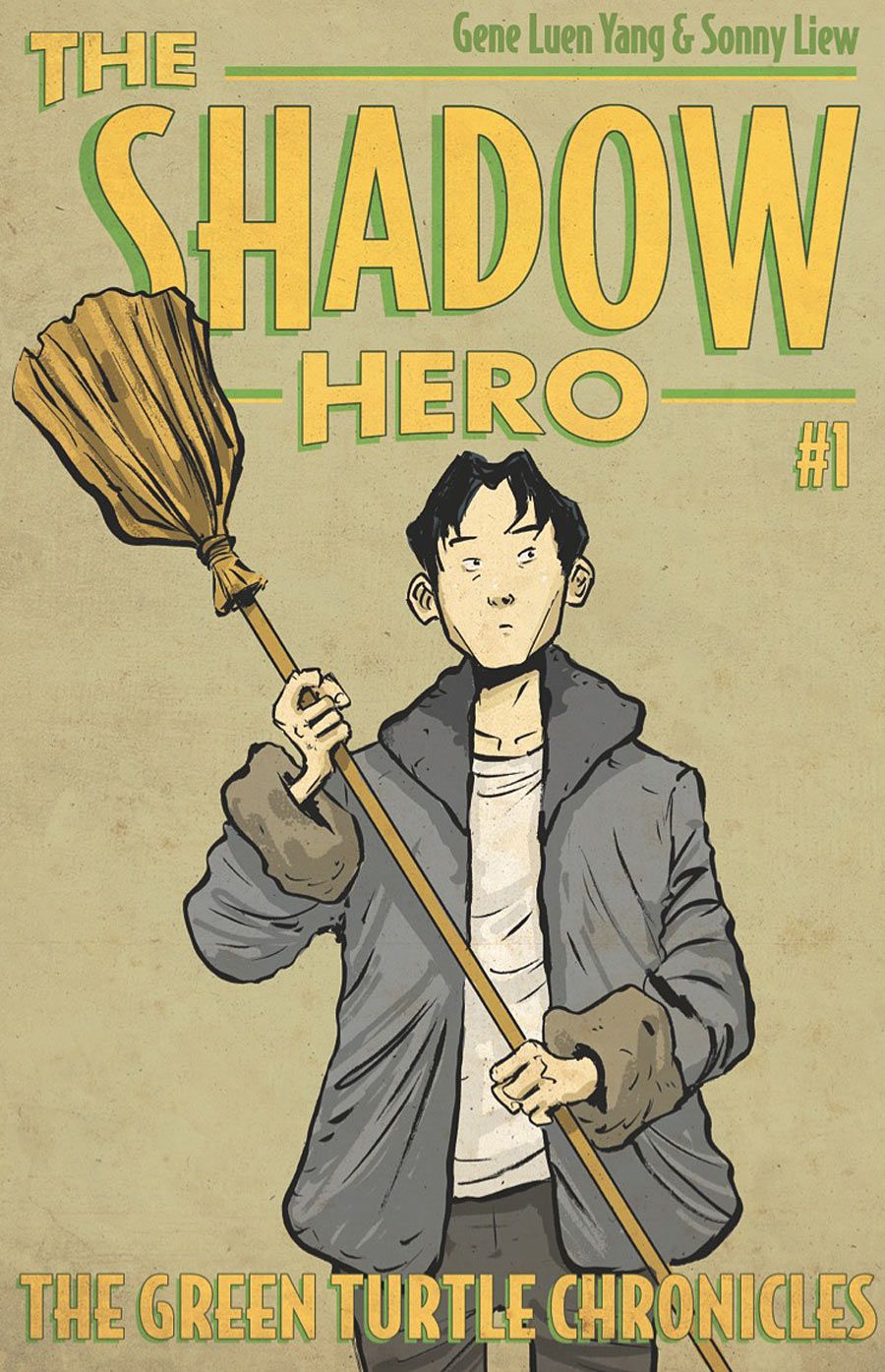

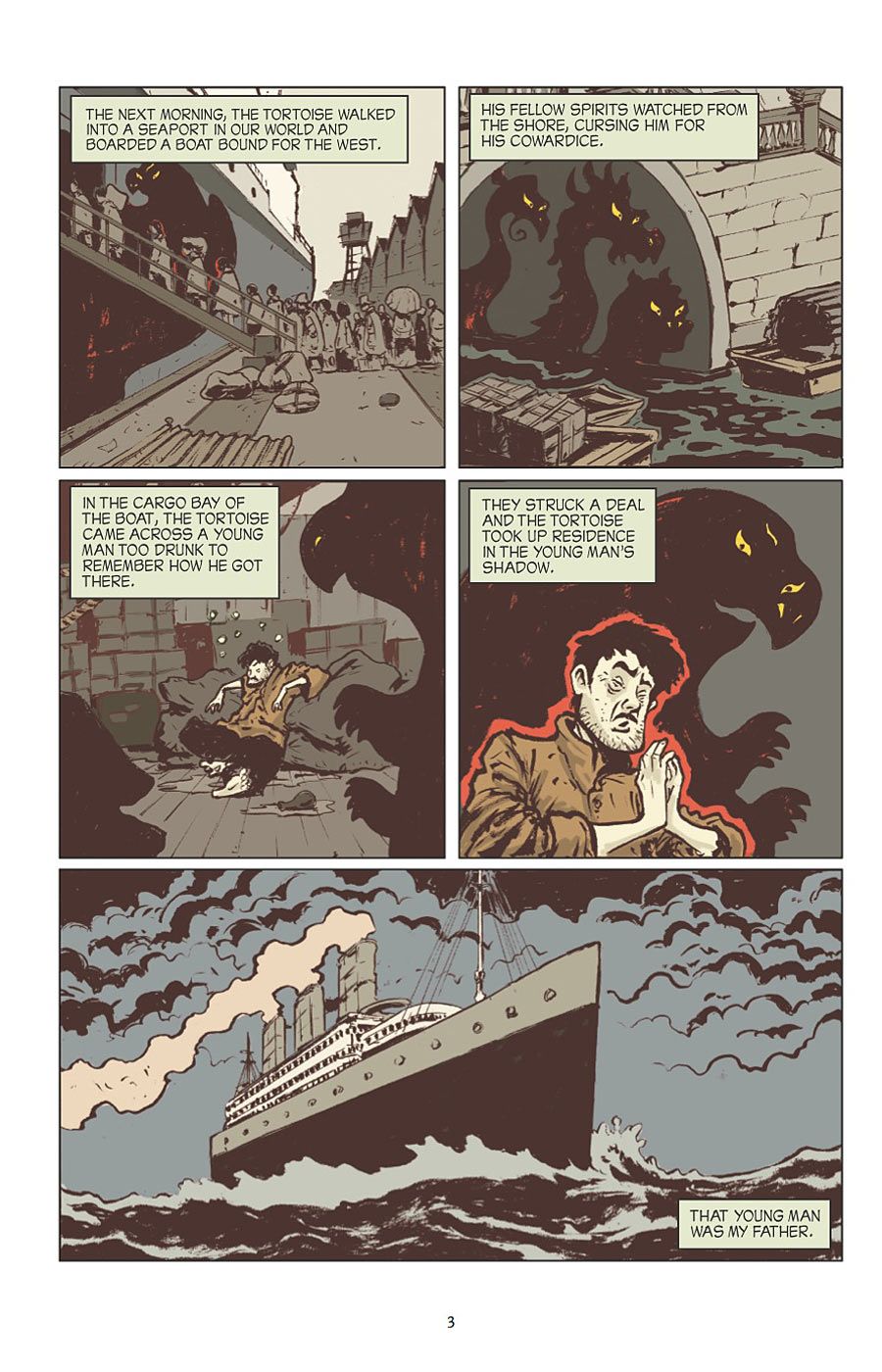

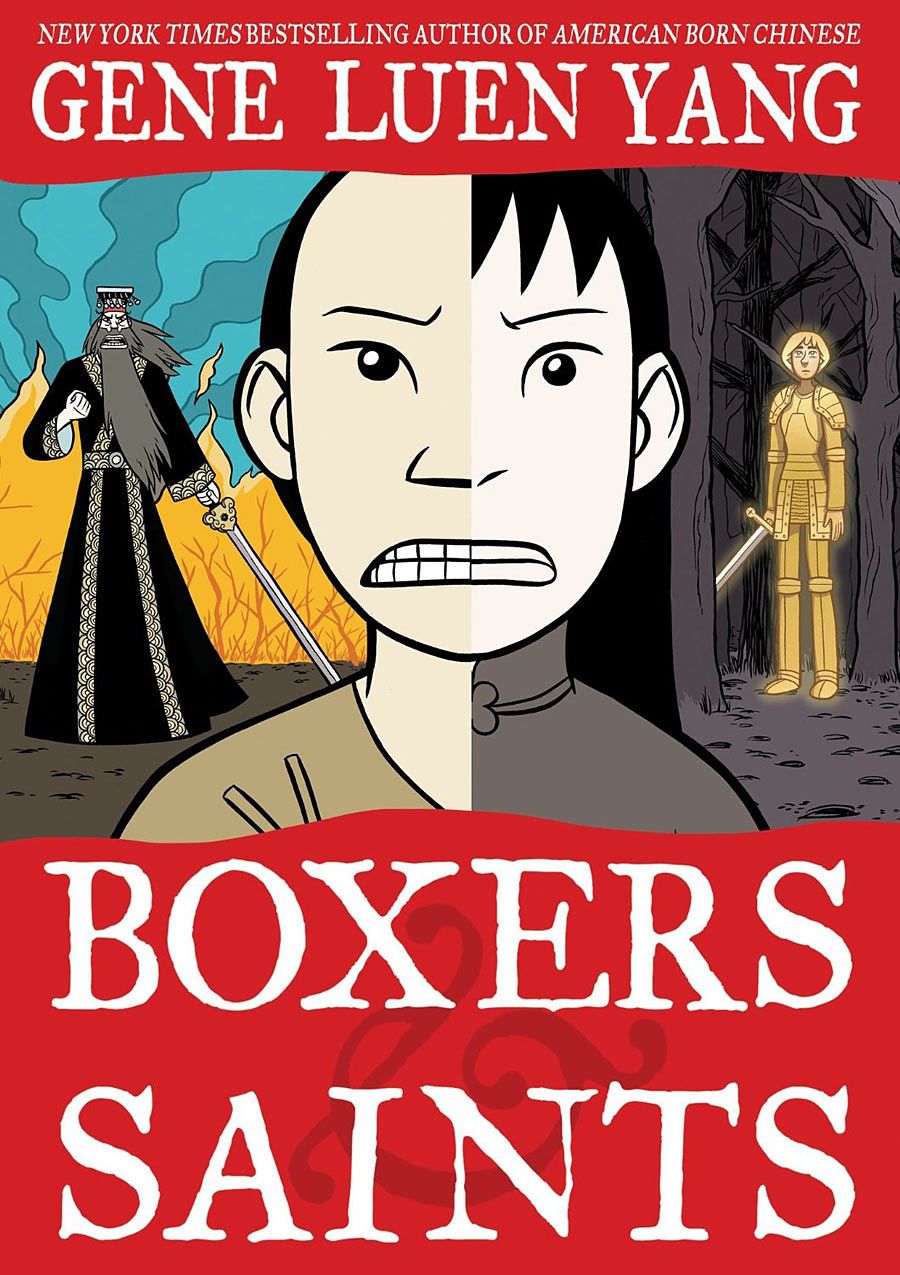

Gene Luen Yang draws upon his experience as a child of Chinese immigrants in original graphic novels like "American Born Chinese" and the "Boxers & Saints" collection from First Second Books. Though he often depicts Chinese culture specifically, his chief concern is the broader examination of the immigrant experience. In "The Shadow Hero," a collaboration with artist Sonny Liew, Yang brings new life to the Green Turtle, a Golden Age character that might represent the first Asian-American superhero. Though never explicitly rendered as a Chinese-American in his original adventures, Yang and Lieu offer a lighthearted reintroduction firmly establishing Hank Chu as the son of Chinese immigrants in a fictionalized Chinatown. The full story arrives on shelves in July, but First Second is also releasing issues digitally on multiple platforms, with the third issue debuting Monday April 14.

CBR News spoke to Gene Luen Yang about the Green Turtle's secret origins as well as the pivotal role that collective immigrant narrative plays in the mythology of superheroes.

CBR News: When did you first hear about Chu Hing and his creation, The Green Turtle?

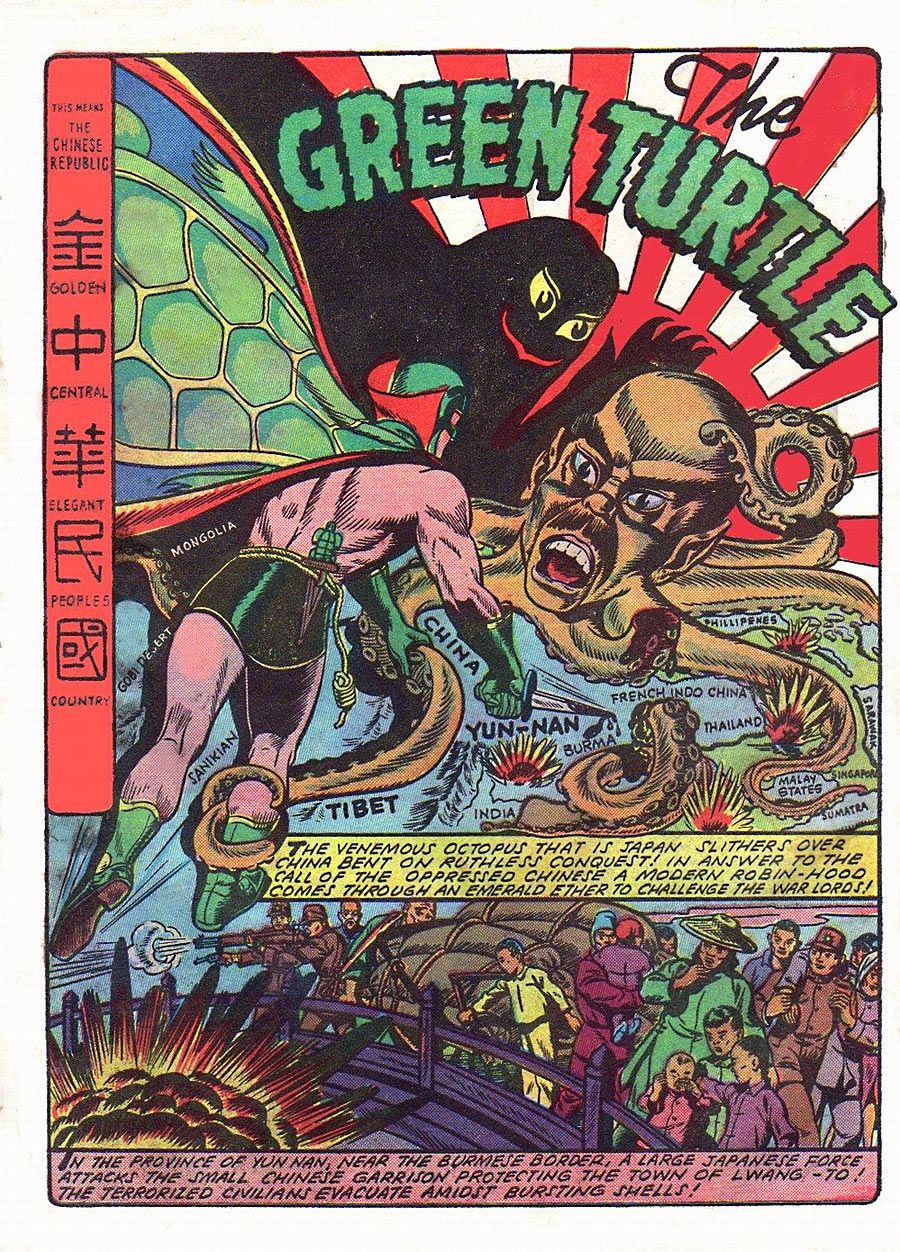

Gene Luen Yang: It was actually through a blog, Pappy's Golden Age Comics Blogzine. It's a blog that features pages and characters from Golden Age comics. One of his entries on the Green Turtle was actually featured on Comics Reporter. My friend Derek Kirk Kim saw it and forwarded it to me. I read it and was just fascinated with the character. I thought it was so crazy. It's kind of awesome now that you can just go online and there are these resources like the Digital Comics Museum where you can download full Golden Age issues, because many of them are now public domain. So I went and downloaded all of the comics that feature the Green Turtle and read them all.

And it's just the five of them, right?

Yeah.

Gene Luen Yang Explores Chinese History with "Boxers & Saints"

Which, in the grand scheme, is not that bad a run for that period. Some didn't make it out of their first appearance. Was he part of an anthology?

He was originally in this series called "Blazing Comics" published by this company, Rural Home. Back then tons of little companies came up out of nowhere, and they would put out some comics and disappear. They were one of those companies.

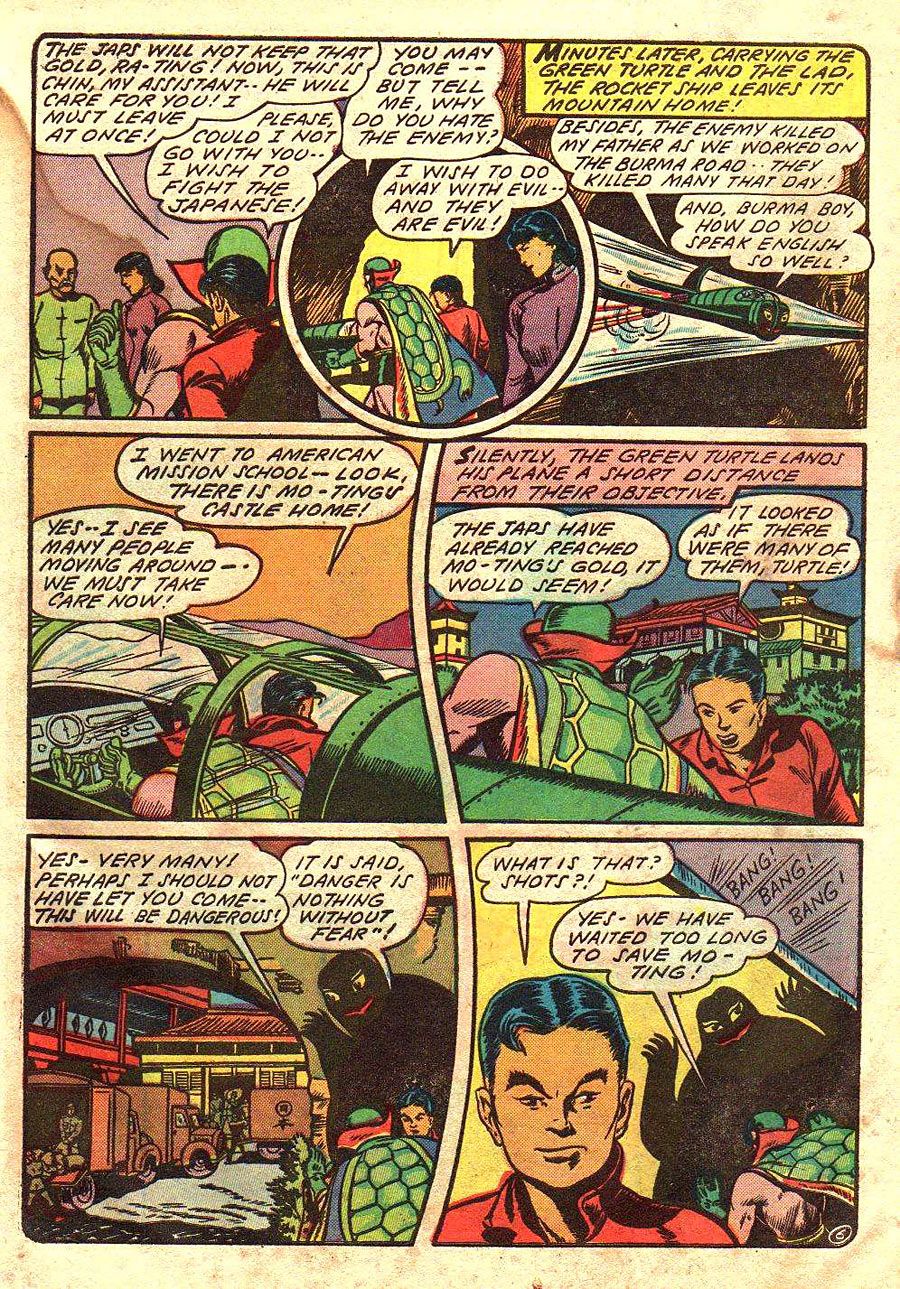

In that video produced to pitch the "Shadow Hero" project, you make a strong case for the validity of an urban legend. It seems pretty clear that Chu Hing came up with some creative ways to depict a Chinese-American hero, going out of his way to avoid showing the character's face. In his mind and in the minds of young readers, Green Turtle could be of a different heritage than all the other heroes on the shelves because he never supplied evidence to the contrary. Have you since discovered whether or not that was his intention?

No, so far it's still a rumor. I asked around to some Golden Age collectors and people who know a little more about that period that I do, and nobody can verify it. That's just the rumor swirling around the industry. Most people don't even remember him. Chu Hing is a pretty obscure guy. He did some work for Marvel Comics back when it was Timely, toward the end of his career, but that's about it.

You make a strong case though. From what I've seen, he was really bending over backward to conceal that face. It's almost like that that scene in the first "Austin Powers" where characters are nude, but pieces of fruit in the foreground block out all the naughty bits. It's not all that subtle.

Yeah. There is one exception though. On the cover of the second issue of "Blazing Comics" you see his face. Chu has him posing next to his sidekick, a kid called Burma Boy. Their facial features are pretty similar. Burma Boy is identified within the comic as Chinese. And in this one portrait of the Green Turtle it does seem like he meant for him to be Chinese. But nobody knows for sure.

Did you have an interest in the Golden Age prior to all this?

I've loved superheroes since I was a kid. I've loved comics since I was a kid. I grew up in the '80s and '90s when, in America, if you were into comics that meant you were into superheroes. There was very little of anything else around. I grew up reading Marvel and DC Comics -- mostly Marvel because I thought DC was kind of stupid. [Laughs] That lasted all the way through late high school, and I started getting into indie stuff. The Hernandez brothers, and I think "Bone" was just starting up at that time, so I really got into Jeff Smith. But I do have this lifelong love of superheroes that predates logic. I have a visceral connection with them. If you love superheroes long enough, you'll eventually investigate that Golden Age material. I'm no Golden Age expert, but when I look at them I have a feeling of nostalgia even though I was not around when they were first published.

How long did it take to realize that this forwarded blog post about an obscure Golden Age hero was more than just an item of novelty, but something you wanted to pursue in your own work?

After I read that blog post I just couldn't stop thinking about it. I couldn't stop thinking about the way the pages were composed. I couldn't stop thinking about the rumors surrounding this character's creation, and whether they were true. Green Turtle wasn't popular, so he only lasted five issues. It was cancelled before we ever find out this character's secret origin or his full identity. Chu Hing never confirms for us. I kept thinking, "Man, it would be awesome if somebody would figure that out." I thought that was really inspiring. Even beyond that, the more I thought about it, the more I saw a connection between the immigration experience and superheroes. Most of the superheroes we know today, most of the popular ones, were created by immigrants' kids. Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Bob Kane, Bill Finger -- they were all the children of immigrants. Consciously or not, they embedded their experience within their comics, within their heroes. So every superhero has these two different identities. They operate in two different worlds, under two different sets of expectations. I think that mirrors the experience of a lot of us immigrant kids. A lot of us speak one language at home and another one at school. We often grow up with two different names, a "foreign name" at home and an "American" one at school. We grow up with two different sets of expectations. Navigating between two worlds and two identities -- that's mirrored in those comics. I don't think it's a coincidence that the creators of Superman and Batman, all these characters that negotiate two identities, that their creators were children of immigrants. The more I thought about the Green Turtle, the more I saw it as an opportunity to explore that connection.

Yang Takes "Avatar: The Last Airbender" to "The Rift"

My mind immediately went to Superman as a cosmic Moses, but it really does extend to so many of those characters.

Absolutely. He's cosmic Moses. Superman is the prototypical superhero, but he's also the prototypical immigrant. His parents basically sent him to America for a better life, right?

But you're adding a new dimension to that, I think. At least with western superhero comics, we're looking at the Judeo-Christian allegories as understood, often forgotten subtext, while anything Asian -- culturally or philosophically -- is, by default, exotic and strange. So it seems like there's definitely room for revisiting that metaphor through the experience of Chinese immigrants and some of the specific nuances not included as part of that Superman catch-all.

Yeah, I think in general, most American superheroes are white, and I don't think there's anything malicious behind that. It's just a product of how the genre developed. Superheroes were born in America when America was a very different place. Now we're seeing this push toward diversity, within all media but especially within superhero comics. Online there's this very vocal contingent that really wants to see diversity within superheroes. That really makes sense to me. As a Chinese-American, as an Asian-American, in the rare instances when I encounter an Asian-American superhero, there's something about superheroes that embody the ideals of what it means to be an American. When I encounter an Asian-American superhero, it's almost like a visual reminder that I'm a part of this place, that I'm a part of this society. Even if in different points in my life I've felt like an outsider. I think that's what's driving a lot of this push towards diversity. We want to see a visual representation that anybody can be a part of America.

I was revisiting "American Born Chinese" this weekend, and that metaphor of Jin wanting to be a Transformer when he grew up got me thinking about the current "Ms. Marvel" series. Here you have this young Muslim girl, a wallflower, with shape-changing powers. She transforms, sometimes into her idol, who happens to be a statuesque blonde. At the time, it struck me as a great metaphor for coming of age, but it also must speak to the immigrant experience. Do you suppose that's a universal anxiety, that desire to transform?

I think so. I think that's true for anyone who finds themselves a minority within a majority setting. I haven't read that "Ms. Marvel" book but I really need to. I keep hearing awesome things about it. But for "American Born Chinese" I just thought that with Transformers there's also that dynamic, right? It's a very physical embodiment of this idea of negotiating two identities. Every Transformer has a robot form and a vehicle form, and they go back and forth. That's why I wanted to include that as a way of talking about the experience of an immigrant's kid. I think it's a pretty common thing though. A lot of people live in between cultures, live in between worlds. At some point in their lives they go through a period where they wish they were just part of the majority, that they didn't have to negotiate identities, didn't have to switch codes when they went from home to school. At the same time, it's definitely not unique to Asian-Americans. It's not even unique to the children of immigrants. I just think America's such a diverse place that we're kind of a collection of subcultures. Whenever you go from one to another, you're going to feel some of that tension.

On your blog you talk about some of the process for "The Shadow Hero" and summoning all of the written Chinese you can remember from Chinese School to fill in one banner as placeholder text for a thumbnail drawing.

[Laughs] That's right.

For anyone who didn't grow up with that experience, what was Chinese school like?

So, I grew up going to Chinese school every Saturday. I was very bitter about it as a kid because I'd have to miss all the cartoons. When I first started, there was no such thing as a VCR. There was no way I could record these cartoons. I was so bitter about it. Then we finally got a VCR, and it wasn't like an iPhone; I found it so hard to program. I would always miss recording "Spider-Man and His Amazing Friends." That's the one I really wanted to watch. That and "Dungeons & Dragons." That might have been why I didn't pay a lot of attention. I wasn't as diligent about my Chinese school homework as I was about my regular school homework. Then eventually when I got to junior high and high school, even though I didn't take the work seriously, I actually felt more at ease there, on some subconscious level. There were these girls at Chinese school, and they'd be the same girls from regular school, right? But at regular school I was too intimidated to talk to them. At Chinese school I could, for some reason. I never figured out why. Looking back as an adult, I think that came from the freedom of suddenly being part of the majority, especially when you're a junior high kid and self-conscious about everything. My ethnic heritage, in regular school, was something I was super self-conscious of. That was off the table at Chinese school. So, I got this confidence with the ladies. [Laughs] Not that it did me any good because I couldn't get a girlfriend, but I could at least talk to them, you know?

Considering all of the projects you've been working on, and those links to China and its history, do you wish you'd pursued that language longer, even more studiously?

I think my parents were right. My parents told me as a kid, 'If you don't learn this, you're going to regret it as an adult.' And I didn't learn it. At least, I didn't learn it as well as I should have. I do regret it. I feel like there's a piece of me or of my past that's incomplete. One of my friends -- Jeff Yang, who writes a column for the "Wall Street Journal" -- he explains culture as a bucket of water passed from one generation to the next. Every time you pass it, you lose some of the water, right? Chinese school and learning the language is one way of trying to keep as much of that water in the bucket as you can. That's what I'm doing with my kids. I dropped the water when it was passed to me, and now I want to put some of that water back with my own kids.

CBR TV: Gene Yang Talks "Avatar: The Last Airbender"

Do you think that's why you tell the stories that you do?

Yeah, because I feel guilty that I didn't pay attention in Chinese school? Maybe. [Laughs] Maybe. I do think that the advice they give to write from your life is a cliche, but it's also true.

As I've gone through my cartooning career I've seen how important research is to any story that you tell, no matter how fantastical. Even licensed stuff. When you're writing from your own life, a chunk of that research is already done. You already have your memories. That's why I gravitate toward stories of cultural heritage.

Stay tuned to CBR News for more on Gene Luen Yang and follow him on Twitter at @geneluenyang.