Welcome to the CBR SUNDAY CONVERSATION, a weekly feature where we speak in-depth -- and at-length -- with some of the most interesting members of the comic book community. These discussions run the gamut in terms of topics, from current projects to classic stories, talking trends, tastes and wherever else the conversations lead.

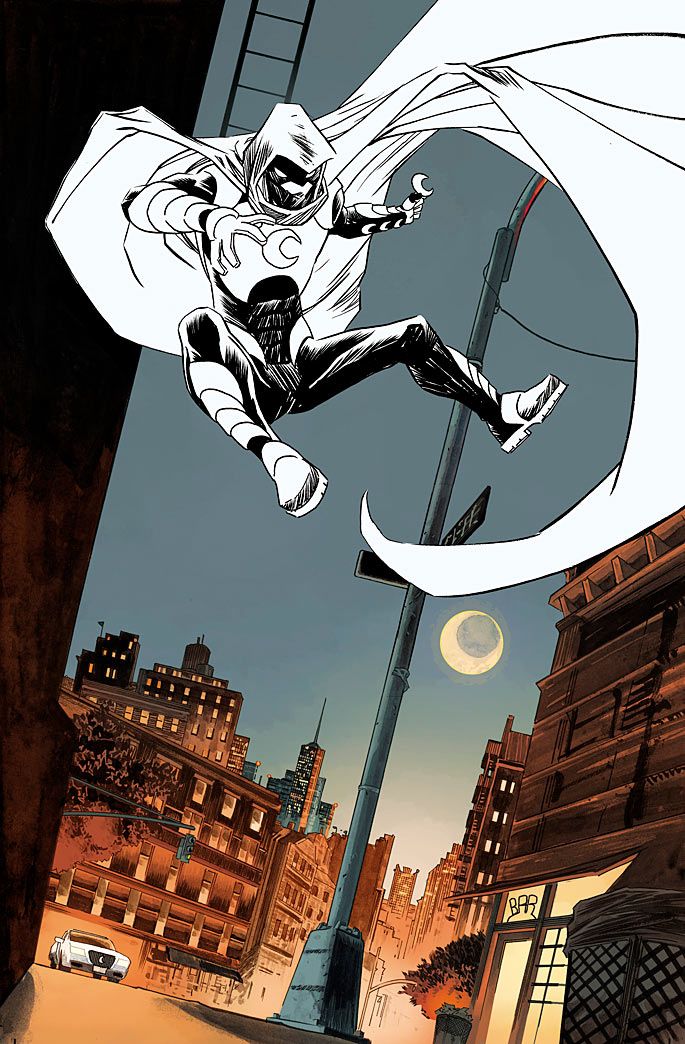

Irish artist Declan Shalvey readies Marvel's all-new "Moon Knight" series for a March debut. Though writer Warren Ellis keeps him on his toes with compelling scripts, Shalvey continually seeks out additional ways to set the book apart visually, and to challenge himself as a storyteller. Perhaps the most striking decision he's devised with colorist Jordie Bellaire is the subtraction of color, even mere accents, from the main character. It lends the mystic vigilante an ethereal quality, and serves as just one example of Shalvey's ever-thoughtful presentation.

This week, CBR News catches up with the artist to discuss interests from without that continue to drive his growth as a storyteller. As it turns out, hard labor and some homespun Vulcan philosophy play a significant role.

CBR News: The only downside, talking now, is that you haven't seen Spike Jonze's "Her" yet. From past conversations, I know that's likely quite high on your list. Tell the people about your interest in science fiction, specifically that topic of artificial intelligence.

Declan Shalvey: For those who don't know, I was telling Paul about a thesis I wrote in my final year at art college, on artificial life in science fiction. Basically because I was a huge "Star Trek" nerd. Art college was really good for me because it got me reading stuff I might not have read otherwise, books on ethics and morality. Feminism. I didn't know there were books I could read on those subjects. I got into reading a lot of philosophy, many of them looking at science fiction. You know what, actually? Every bloody book regarding ethics, morality, artificial life -- it was all "Blade Runner." Every bloody one. Well, there's a lot more to science fiction than "Blade Runner." It's kind of a frustration of mine. Remember when that movie "The Butterfly Effect" came out? "Ah, this movie is brilliant! 'The Butterfly Effect!' There's all these different realities!" I'm like, look, "Star Trek" did that years ago, okay? So it's bugging me a little bit, with what I know about "Her," that "Star Trek" did that years ago as well.

Ellis, Shalvey & Bellaire Put a New Face on "Moon Knight"

[Laughs] The Geordi episode, with the hologram?

Yeah!

I love that one. Well, both of them. It's not a two-parter, but it's told over two episodes with some space between, right? First he falls for the hologram--

The Enterprise is stuck in this thing and he has to create a mock-up of the Utopia Planetia Fleet Yards, and what was it, Dr. Brahms? A program based on the woman who designed the ship's warp drive system.

And Geordi being Geordi, he falls for this program, which is essentially based on records and interviews with the real person.

Then later on he meets the real Dr. Brahms, and she finds out about it. Clearly I know this stuff way too much.

You got me with "Utopia Planetia Fleet Yards." That's a great storyline though.

And especially prophetic when you consider internet personas now, how we can have a relationship with the idea of somebody, without actually having an in-person relationship. There are plenty of people I met on Twitter. I met Jordie [Bellaire] through Twitter. [Laughs] That relationship changed. I'm going to Emerald City Comic Con this year and meeting Evan Shaner and Mitch Gerads for the first time, even though I've interacted with those guys for years. Considering that story is well over twenty years old, that's really prophetic.

It's almost like knowing a draft of a person, especially with a casual friendship on Twitter. There are many exceptions, but often we're only familiar with one facet of a person's life through some mutual interest or two. But it's still easy to mistake that for something deeper. Then, that's true of countless real-world relationships as well.

When I met Chris Samnee and his wife, after a while she said, "I thought you'd be dirtier."

[Laughs] What?

Like a hobo or something? "No, no! Your sense of humor." I've probably dialed it down since I started going out with Jordie. I certainly have that sense of humor, but I'll often edit myself. Jordie and I were talking about internet personas, and how annoying they are. There's people who carry themselves in a very specific way online. Maybe that's safer. Maybe that's a method of being more private. It is interesting, though, that some really seem to expend a lot of time and effort on honing that character. That persona.

That's also no different than life off the internet, right? Whether it's for the office or navigating between different groups of friends.

Well, I guess we all end up putting on trousers. None of us want to, right? Thinking about any jobs I had before becoming an artist, they were all sort of labor-based, so I wasn't in that office environment. Like, I used to deliver coal, so I'd have to knock on doors and say hello to people, but beyond that--

That seems like an especially Irish thing to do, delivering coal door-to-door.

[Laughs] It was a little like "Angela's Ashes." No, that's why I'm always on time with my pages. I remember those jobs and I don't want to have them again.

Everybody pick up "Moon Knight" so they don't send Declan back down to the mines.

I also worked at a kitchen in a castle.

A castle?

There was an 800-year-old castle next to my house. Tourists would come in and we'd throw banquets for them. The staff would dress up in medieval outfits and do songs. But I worked in the kitchen where we didn't have to do any of that. And it was -- they were all filthy in there. There's no such thing as professional conduct in that castle's kitchen. It was all sex jokes. Sex jokes all of the time. So, I never was in a work environment where I'd report to a manager.

I feel like it's important that we revisit your "Downton Abbey" by-way-of Anthony Bourdain experience at some point in the near future, but let's return to the pressing subject of robots and their civil liberties. Why do you find those stories so attractive?

I think it's a quote of Warren Ellis' I saw, about science fiction being social fiction. That's part of my argument regarding "Star Trek" functioning as science fiction while "Star Wars" does not. "Star Trek" was able to talk about issues of race before you could talk about race. It was able to talk about transgender before that was really done on TV. The modern "Battlestar Galactica" was doing its critique on the war in Iraq. You can talk about things, discuss things, explore things, dramatically. There's that episode in the second season of "Star Trek: The Next Generation" where a Starfleet scientist wants to take Data apart and see how he works. It's potentially a really boring episode because it's essentially a courtroom scene.

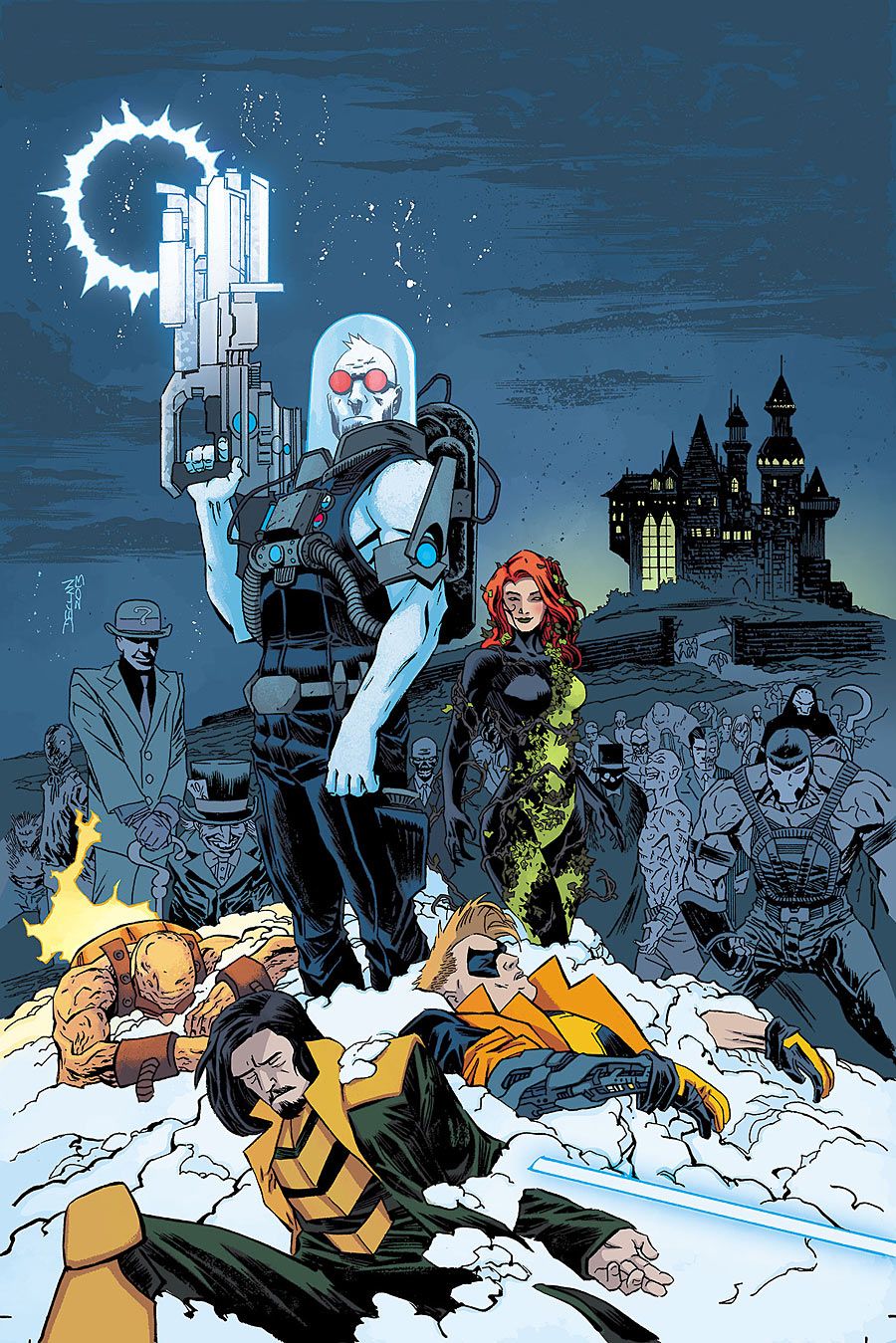

Duggan & Shalvey Bring Out "The Good, the Bad & the Ugly" in "Deadpool"

But they heighten it with that science fiction element.

And also by the fact that you love Data. Anybody watching that show at that time loved that character. Visually, it's not a terribly interesting episode because they're just in that room. But put Brent Spiner and Patrick Stewart in that room and you've got gold.

I think it's also that wrinkle of Riker forced to serve as the lead prosecutor. Because we empathize with that character, too. Just speaking as a bearded man myself, Will Riker is one of the pioneers.

And he delivers a very convincing argument, you know? So, I used that episode, "Measure of a Man," and "I, Borg" -- that's a great one in that it shows Picard's clear prejudice against the Borg. It's almost tough to watch because he's been built up as this nearly infallible father figure. It's a real slap in the face to see him so conflicted. That one also goes back to that utilitarian argument about the greater good. "The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few."

"Or the one."

I love moral arguments, especially gray areas. That's one of the reasons I always liked superheroes. Not because of the gray areas, but because of right and wrong. I was always into moral fables, which is what superheroes really are. As I got older, I got more interested in the gray areas. Great science fiction is capable of making you rethink your point of view. If you're watching a story about aliens being forced out from their home, most will go, "That's not right!" Then you apply it to something like Northern Ireland or the Middle East, and all of a sudden there's these question marks over an issue you once felt resolute about. If I raise a political argument, take a stance on something, it can very quickly devolve into a more heated debate, because they get their back up. Divorced from current politics, there's a chance at reaching a more objective perspective on that very same issue. That's something fiction's very good at; presenting the world without the blinders you've put on in life. So, while those "Star Trek" episodes are about artificial life and the ethics of A.I., and that has more of precedent in the real world now, they're more generally about morality. Look at the episode with Data's daughter, which is telling a broader point about parental responsibility. They're using science fiction to talk about something else entirely. For "Measure of a Man," it's about personhood. Human rights. Then there's the movie "A.I." itself.

That's a... hat's a difficult movie.

It's certainly not perfect. It's got its problems. It's two different movies trying to be one. It was flawed from the beginning, but there's a good movie in there. It was kind of like trying to revive a corpse. Some things worked and some things were never going to work.

From two very different filmmakers.

Very different. Very Spielbergian things and very Kubrickian things. Not perfect, but definitely worth seeing, in that it was interesting.

Interesting might be more important than bad or even decent, especially if the end goal is conversation.

They fell flat on their face, but they tried. I'm fine with that.

What would you say to someone who said that science fiction served its purpose in sneaking what were once subversive fables about social justice past the censors, but that these days it doesn't seem so bold to hide behind bat'leths and ridged foreheads, that moral arguments should be posed more directly?

Well, I would say to that person, Paul--

[Laughs] I'm not saying that.

It's not necessarily that you have to hide it, but a lot of people continue to form baseless opinions on things. When you present things in a narrative they've already accepted, you bypass the barriers they've thrown up out of baseless conditioning.

You also put a human face, for lack of a better term, on an issue that, up until that point, audiences might only have considered in the faceless abstract. We like Data. We like Picard and Riker. The questions means something more now.

That's probably the best one because you're hinging on an emotional argument there. It also helps that Riker offers a very logical argument which he himself doesn't agree with on an emotional level. But I'm mostly thinking about prejudice and sexism. Especially in America, there seem to be very hardcore groups whose heels are completely dug in on certain issues. It's very easy for us to hear something and form an opinion on something without giving it much thought beyond that initial emotion. Take "The Wire." I had no idea any of that was going on. On the news, I might be so jaded as to shrug it off, "Oh, okay." What fiction can do is bring you into that world in a very immersive way, show you things you hadn't thought about or felt, putting that face on these issues, from poverty to substance abuse to race to political corruption. Fiction can change your mind. It doesn't have to, but it can set those things in motion.

Parker & Shalvey Re-Assemble Marvel's "Dark Avengers"

A lubricant for change.

A lubricant for change. Whereas science fiction can work on an additional level beyond that. I mention "The Wire," but if I were a racist, I might not want to watch a series about black people. For that level of prejudice there's alien white people on "Star Trek" with freckles on their forehead, you can tell some of the same kinds of stories.

Devil's advocate: It's also been argued that science fiction can, in fact, harbor racism, even on a subconscious level. While there are many progressive, well-meaning writers using science fiction in the way we've been describing, there are those who might exercise their bigotry by casting a Klingon or an orc as some other race, as the savage, as the "other."

Definitely. That's a perfectly fair argument. I would say though that science fiction can use the more positive model in ways that other fiction cant, while traditional fiction is also capable of that negative model as well. I don't think it's specific to science fiction. You can hide anything -- good or ill -- in science fiction, but that's ultimately a valuable tool to have.

You said that you appreciate the gray area of moral arguments. For some, those exercises in fiction can be taxing, especially when it's so open-ended. Is there still satisfaction to be wrought from an argument that isn't resolved in the end?

I do personally like it when the answer isn't right there. Reading books about philosophy in college, I remember that feeling of confusing. I was looking for answers. I'm not religious, despite being raised Catholic. So, what's the answer? I came across this quote saying, the answer isn't the thing. To ask questions is the point. Not knowing answers is fine, but the fact that you're asking questions is, in itself, a worthwhile experience.

For more on Declan Shalvey follow him on twitter at @declanshalvey