Sarah Glidden made a splash in the comics industry when Vertigo released her debut graphic novel “How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less" in 2011. In the years since then, she’s released a number of short comics that run the gamut of relating stories about her life in Argentina, to a profile of Green Party Presidential candidate Jill Stein.

She was also working on her followup long-form project, "Rolling Blackouts," which is out this month from Drawn and Quarterly. The book details a trip Glidden took in 2010 to Turkey, Iraq and Syria with a group of journalists reporting on Iraqi refugees. In a conversation with CBR just ahead of the book's release, Glidden spoke about how she works, the ways the Middle East has changed in the intervening years since her trip, and how she thinks about journalism.

CBR: “Rolling Blackouts” is your account of a trip you took shadowing a few journalists in late 2010, a long time ago in the Middle East when things were very different.

Sarah Glidden: Things were very different. Going into it, I was like, no one’s going to be interested in a book about Syria. This was a country that we didn’t pay any attention to before this war broke out. It was one of the most tourist-frequented Middle Eastern cities because Damascus is beautiful and has so much history and people are really friendly. It was an interesting mix of Christian and Muslim and then had a real international crowd. I could never have seen in a million years that this would have happened, but of course what did we really know about what was going on there? It was a long time ago in terms of what has happened since then.

As I explain in the book, I have known these journalists that I went with on this trip for about 15 years now. We became friends in our early twenties, and they started making journalism together around the same time that I started making comics. I thought it would be really interesting to go with them on one of these trips and do a comic about how they work, how journalism works. By the time I was finished working on the Israel book, they were about to go on this trip to Northern Iraq and Syria to report on Iraqi refugees. If the timing had worked out differently, I might have gone with them to Pakistan where they went a year earlier, reporting on education issues. If I’d gone a year later, it would have been to Ukraine and some of the other former Soviet states where they were looking at youth culture.

Your goal at the beginning was to document what they did and how they work.

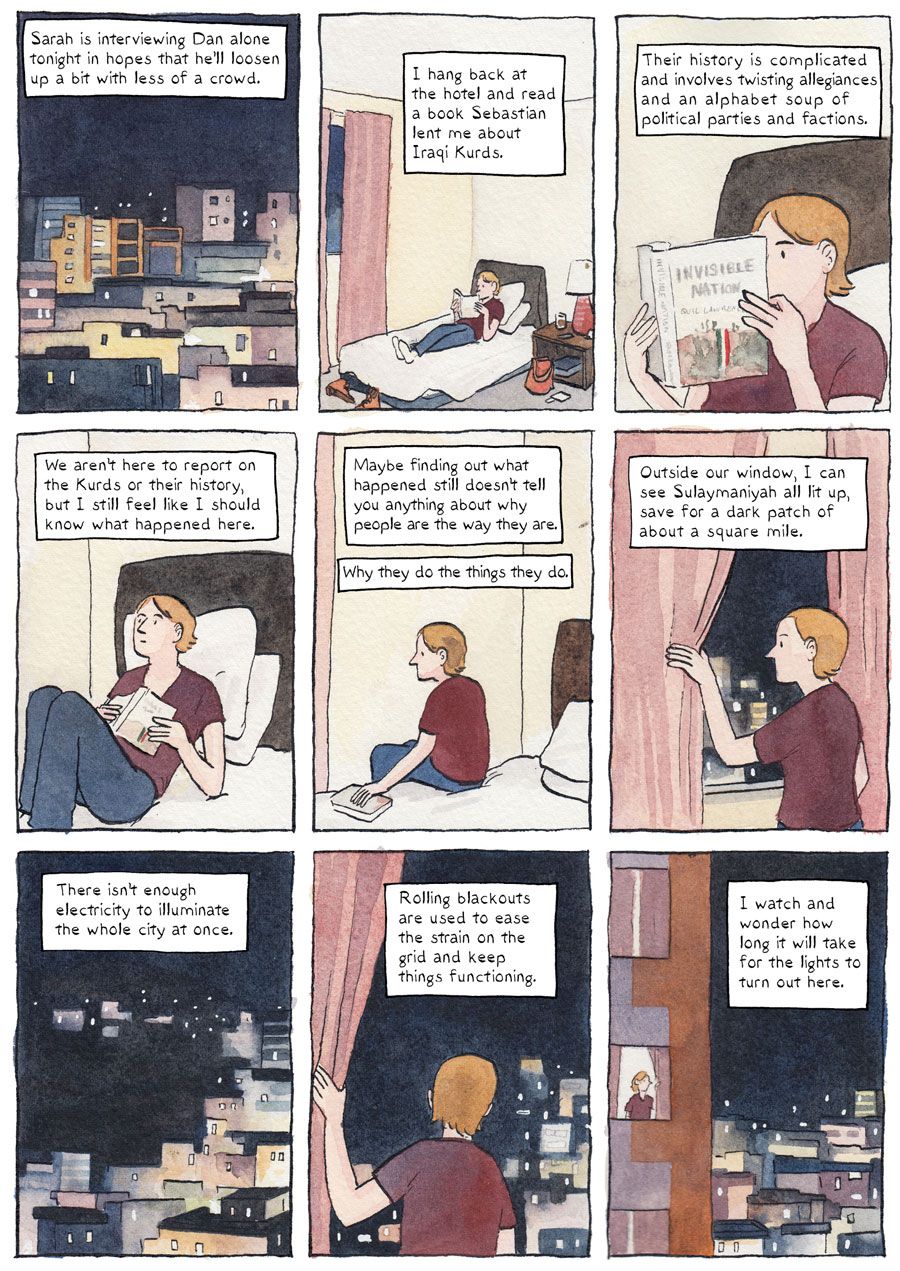

Journalism was something I almost took for granted. I was a big New York Times reader, ever since I started paying attention to journalism. and it was easy for me to think the New York Times is objective. It’s the best newspaper. After 9/11 happened -- I was 21 when it happened -- I realized there was a lot of stuff I wasn’t aware of and I wasn’t paying attention to. Then, when I went to Israel for the first book, I realized how little is reported outside of the drumbeat of that conflict. I wanted to look more into, how is the sausage made and how do reporters choose who they talk to and choose what to report on and how much is an editor involved with bringing those stories into the open? If journalists could chose, there would probably be a lot more and different stories out than there are. Basically the whole point of the trip was to get a look behind the curtain to see how this functions. It ended up of course being a lot more layered than that, but that was the original idea. I thought it was going to be pretty simple open and shut project. [Laughs] It was not. Probably for the better.

Sarah and Alex were very open about how they work, and also how they think about their work.

Yeah they were very open to the idea. I think a lot of people, when they’re talking to a journalist, either don’t realize that they might not come out of it smelling like roses, and they also might think that the journalist is trying to help them. Sarah and Alex always knew that they were putting themselves in a spotlight and they might not come across looking very pretty. I think, especially for Sarah, it was very important to experience the other side of things. She’s made this career out of talking to people, telling their stories, and sometimes having to portray her subjects in a less than flattering light. She wanted the mirror to be turned on her and to see what it feels like to have someone else report on her. They were very open and I think it was really important to them–more than how they come across–how journalism is shown to people in a more transparent way. It’s something that they care about a lot. They know that there’s a lot of misconceptions about journalists and how they work.

Both of them make it clear that they’re aware of the challenges and ethical dilemmas all journalists face, but they also talk with you about how they need to think about marketing because they’re trying to sell it to an outlet and they have to think about readers. That something or someone is an interesting story just isn’t enough.

It’s a side of journalism that doesn’t look too good when you’re talking about it. Journalism is not just for fun. It seems like it would be great to just be able to go around asking people questions to satisfy your own curiosity, but that’s not the job. The job is to take these stories and hopefully pass them along. They really do have to think about those issues and sometimes the stories don’t get told. There are a bunch of people we talked to on this trip that either their story couldn’t become a feature or someone we talked to for three hours became a couple sentences in a bigger article. It was interesting seeing that. It was a part of journalism I didn’t really think much about, the marketing side of things, but it is really important. I think journalism is an important profession and I think we need more of it, not less.

Going into the book and then later, did you have ground rules about how you were going to work?

I knew that I didn’t want this to be another memoir. I wanted to really step back from being part of the story, but I also included myself because it gives the reader someone to bumble along with. As far as rules, in the first chapter my character gets overexcited and tries jumping in on an interview. Sarah the journalist–I know it’s confusing that there’s two Sarahs but I think people can handle it–gently was like, hey, let’s be careful about boundaries.

It was a weird trip in that I was their friend reporting on them. Sarah is friends with this ex-marine and she’s reporting on him. A lot of the boundaries that are usually part of journalism–that journalistic distance that you’re expected to have with your subject–weren’t there. I knew that I really wanted the dialogue to be real dialogue. I didn’t want to recreate conversations the way I had to do with the Israel book. All of the conversations in the Israel book were true to the spirit of what happened and were true to the subject matter, but I was forced to make things up, and I definitely didn’t want to do that with this book. Almost everything is taken from actual recordings. Those were the rules that I started with, to record and observe as much as possible and then try to figure out how to make it into a book that wasn’t 900 pages. [Laughs]

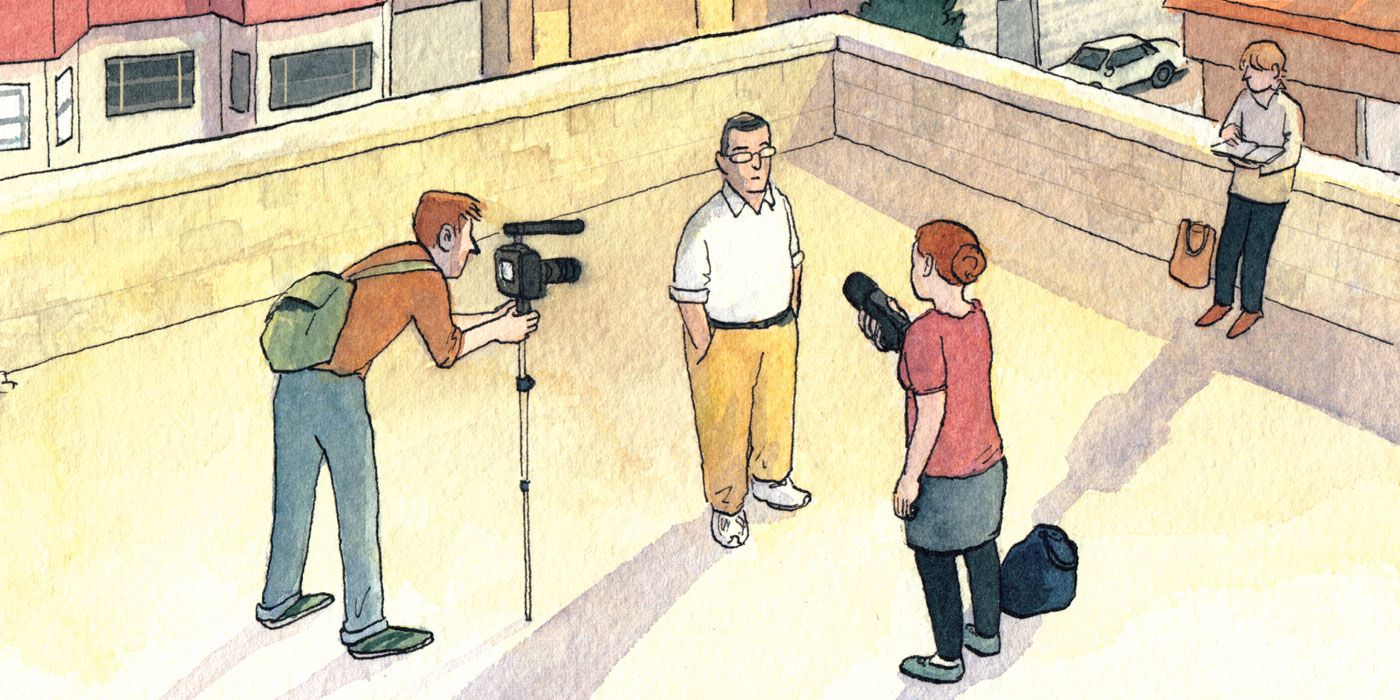

Because of the focus of this book was on storytelling and on the actual interviews, I tried to stay away from depicting the stories that were being told. That part of comics journalism is something that I stay away from just because at this stage I’m still a little uncomfortable trying to re-imagine someone else’s life. It’s something that I think is sometimes necessary to tell a good compelling and clear story. Joe Sacco does it really well. He really researches what clothes people would be wearing, what would a house look like, he gets photo references, he asks people, where were you sitting in the room? It’s not something that I want to avoid completely forever, but for this particular project I wanted to keep that kind of recreation to a minimum and do as much as I could of what these interviews looked like. What is the body language someone uses when they tell their story. How are people sitting when they’re doing interviews.

There are moments of that, to be sure. I think my approach to journalism is being a little bit flexible with things like that. As long as you’re being truthful. My responsibility, like the journalists, is to make people read the book and can follow along and learn something about journalism. If having hard and fast rules like that would make it more difficult for them to be immersed in this story or for them to be connected to the characters, then I don’t think that would be doing a service to the story that is being told. I tried to be a little bit flexible with that.

When you had those transcripts, how did you decide what people to highlight, which conversations to include?

I transcribed pretty much everything. When I first started this project, I was a beginner and over the past six years that I’ve been working on it, I’ve done more projects on my own. It was a really messy process. I would print stuff up, cut things up, highlight passages that I thought would be good. I would think a lot about what am I trying to convey with this scene? Who are the main characters of the scene and what doesn’t need to be there? It’s hard because everything’s important to you and everything everybody says is interesting, but you have to edit and I revise a lot. I would write a scene one way and then throw it out and do it over. I always started with those transcripts that took a really long time to do and I hated doing. It was a mysterious process that didn’t always make sense. Maybe this happens to other people, but you somehow write a chapter and you don’t remember doing it. Probably because you don’t want to remember how agonizing it was to figure out what to cut and what to include. You just keeping doing it until your gut tells you that it’s done, I guess.

You also color the book, and the watercolors look beautiful, but I imagine it’s very time-consuming and complicated.

It is, but the painting side of things is kind of like my reward. For me the reporting is the fun part, the writing is the hardest part, the transcribing and writing and editing is the really hard part, penciling is technically difficult but fun, and inking and painting for me are the icing. That’s when I can listen to podcasts and listen to TV shows in the background and focus on how the colors look. Painting has always been really enjoyable to me. I would usually pencil and ink two pages on one day and then watercolor those two pages the next day. The watercolor days were my favorite days. I’m pretty fast because I have a pretty loose style–which sometimes I call sloppy and then people say, no, it’s loose–but it’s the writing part that takes the longest for me. I think if I could be a faster writer and edit a little bit less I could knock out projects faster.

A lot of people read your profile of Jill Stein that you made for The Nib a little while back. Can you talk a little about that comic and how you approached it?

It was an assignment. The week I was doing the final touches on “Rolling Blackouts,” Matt Bors came to me and asked me if I wanted to do a magazine style profile on Jill Stein. I had barely heard of her, but I was so excited to get an assignment. I love assignments because it’s something that I might not have thought of on my own. It was challenging because I’d never done a profile before.

It was great because there’s a certain depression that hits when you’re done with a big project that you’ve been working on for years. Like, what is my life now that this thing is gone? So it was awesome because I finished "Rolling Blackouts" and started doing research for that piece. I took about a month of reporting and then a month of writing and drawing and painting it.The Nib contacted her campaign very early on. She hadn’t been getting a lot of press, so we got amazing access to her that if we had contacted her now when things are so much busier we might not have gotten. Matt Bors was very smart to think about doing that then and I’m really glad that he asked me to do it.

After “Rolling Blackout,” was there something you took away from that where you were able to walk into something like the Jill Stein piece and go, okay, I have to do this?

I think journalism is a learning process. Over time you learn more. It was definitely a luxury to be shadowing these two more experienced journalists–and three when Jessica arrived in Syria. Just being able to sit there and watch them do their job was like journalism school for me. I did lots of reading, but being able to watch them work and to ask them any question that I wanted. Like after an interview, why did you ask this, why did you phrase it that way, or what do you think about how it went. I learned so much from them on that trip that I’ve been using since then.

For the Jill Stein piece, a politician is trained to give you the answers that they want you to get. They want to repeat their message so it’s hard to get them to talk off script. That was the first time I had to figure out when to ask her if I could come to her house and how much to push to make that happen. I was able to get her to open up more. You pick up tips here and there. Some other journalist talked about trying to get to your subjects either where they live or work, and if it’s at their home, interview them in the kitchen because that’s where people feel most themselves and spend a lot of their time. “Rolling Blackouts” was the foundation for me learning about a wide variety of interviews. There’s a difference talking to a representative from the United Nations or from an NGO than when you’re talking to someone from a vulnerable population like refugees. You have a different way of talking to them and different amounts of pushing them to get the information you need.

Have you started thinking about your next project or are you working on something now?

At the moment I’m going on this trip for the book. I can’t really do a lot while I’m on the road. This next year I plan on doing a lot more shorter pieces like the Jill Stein piece. I’ve started thinking about the next large project. I’m really still interested in immigration and refugee issues, but not anything that I’m ready to talk about yet.