Mike Carey and Peter Gross have literally and figuratively rewritten classic stories that have been told and retold for centuries in their Vertigo-published series "The Unwritten," repurposing them as exciting new adventures with a boy-turned-wizard-turned-man planted smack dab in the middle of them all.

As the Eisner Award-nominated creative team brings Tom Taylor's five-year journey to a close in 2014 with "The Unwritten: Apocalypse," answers are coming in each issue not only for Taylor, but for the supporting cast that has spawned exponentially over the years, including fan favorite character Pauly Bruckner.

COMMENTARY TRACK: Carey & Gross on "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" #1

Following the release of the latest -- and quite possibly last -- Pauly one-shot in "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" #5, CBR News connected with Carey and Gross to learn more about the final seven issues, including a three-part arc titled "The Fisher King" which kicks off this week.

The long time friends and collaborators discuss Wilson Taylor's parenting skills, the power of social media and how it affects storytelling, how playing both sides is an advantage in "The Unwritten" and whether they have any regrets ending the series after such a well-received run.

CBR News: Over the years, we've discussed the terrible things Wilson has done to Tom, but we've never really discussed the father-son dynamic and whether it's really any different from a dad having high expectations for his boy to play shortstop for the Yankees or striker for Arsenal? Or even a very strict 'tiger mother' driving her children to greatness?

Mike Carey: Comparing Wilson to a tiger mother is a charitable view. [Laughs] The crucial difference is that all those tiger mothers really want is success for their kids. They're driving and pressing all the way because they want their kids to get to the top of the heap. What Wilson has always wanted from Tom is that he will finish his unfinished business. It's much more coldly instrumental.

Peter Gross: And the coldness lies in the fact that he made Tom for this purpose, so from the start, he decided to have no feelings for him. He wants to see Tom as a tool or as a weapon. It reminds me of what Mike did with "Lucifer," which also has a lot of father-son issues.

Carey: I'm obsessed with parents and children. I don't know why.

To your point, in "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" #2, Savoy says, "Wilson made us a savior before we even needed one. He made this shit happen." But do we really know why?

Carey: We have some answers to that question and the whole of Wilson's plan coming up.

Gross: We better have. [Laughs]

Carey: Yes, we are going to have some more answers in the issues to come. Issue #9 is going to be fairly crucial.

I love this idea that the young of Leviathan aren't feeding off the stories of mankind, but rather the places where stories would normally touch the human mind. Has family dysfunction and an inability to connect with our loved ones without the use of iPhones and social media causing this void in our own lives, and not just the fictional ones of the characters featured in "The Unwritten: Apocalypse?"

Gross: I would say that we have just as much capacity for sharing and needing stories as ever; it's just how that capacity gets filled. Maybe it just gets filled in a more isolated way now. Or maybe it's the kind of fiction that gets fed to us that isn't as captivating. One of the running themes that we've dealt with since the start of this is the idea that if our stories aren't strong enough to entertain our fictional needs, then there is a place in us that can get exploited. In our story, those places get used by the Cabal. And in real-life, I always use the neo-cons building up the Iraq war. We all want to fall for a story. For me, what "The Unwritten" is about is that we should be falling for stories that we know are stories, instead of half-truths and lies.

Carey: I would agree with that, but I think as a species, we've always been at the mercy of our tools. Anything that you pick up and use uses you, as well. There is a fair amount of evidence that the changes to our morphology -- our opposable thumbs, our upright stance -- predated the expansion of our brains and facilitated it. To some extent, the first groping we did outside of ourselves to pick up tools properly created the evolution that led to the expansion of the brain. I think we've reached a point in our development where the Internet is a tool that we've created, but it's actually causing cognitive changes in us. It's changing the way we talk about ourselves and the way that we think about ourselves and the way that we relate to ourselves and others. That's something that we've always been nibbling at in "The Unwritten," mostly because of Peter. He's fascinated by technology and the way technology has changed stories, and through that changing, has changed us.

Gross: Stories were a tool that humans created, so story has changed us too. It's like the chicken and the egg. Once we have stories, everything changes.

Carey: I've been reading China Mieville's "Railsea," and he proposes that the name for our species should be homo narrans, or 'story-telling man.'

I like that. I was going to ask you about Pauly Bruckner later, but since you mentioned opposable thumbs, I always love when Pauly rears his ugly head. Do you love that character as much as I do? Or, I guess, love to hate him as much as I do?

Carey: What I love about Pauly is that he is terrible. [Laughs] He's a revolting human being. But he's also a tragic character. He's been on both sides of the divide. He's been real, he's been fictional, he's ricocheted backwards and forwards, he's been alive and dead -- and he's never, never happy. He's never found a situation where he can be happy. And now, very, very belatedly, he's realized that he was in paradise and he has expelled himself. It's like he was living in the Garden of Eden, and he kicked himself out. There is something about his story that speaks to me. Plus, I just love writing his dialogue. [Laughs]

And I love reading it. I keep thinking that I can share "The Unwritten" with my children, and then a Pauly issue comes out and I have to hide them on the top shelf.

Gross: [Laughs] Exactly. And I'd like to add that for all of the times that Pauly has mentioned his lack of opposable thumbs, he actually has opposable thumbs.

Carey: [Laughs] See? He never knows when he has it good.

Another character that has walked both sides of the divide is Madame Rausch, and recently, she asked Tom if he believes "everything must be wholly real or wholly imagined." That's definitely something that we've talked about -- in fact, the very first time we spoke about this series, you told me you considered calling it "Faction" as a nod to the bridge between fact and fiction. Are you in agreement with Madame Rausch that nothing is wholly real or wholly imagined?

Carey: I don't think anything is wholly real. Wallace Stevens has this line, "The spouse, the bride / Is never naked." And it's because she wears a robe of eyes. What he means is that reality is never naked. You never see reality. You only see your perceptions. You can never get through to the thing itself. We live in our minds. We live in ideas rather than in places, and stories are essential to how we shape our environment. They are the ultimate human tools.

Gross: I agree whole-heartedly with Mike. We see it everyday in life, when you try and relate something factual that you might have remembered. And I have sensed this more since working on "The Unwritten." You stray from the narrative. You try to convince someone of something, and you think you are being factual, but you're adding to it. You can't help but keep weaving the story, 24 hours a day.

Carey: In "Thinking, Fast and Slow," Daniel Kahneman talks about the default settings of our minds. In the psychology experiments that he describes, you get judges and magistrates, you give them the details of a case, and he asks them what sentence they would give to the offender and how many months, but he makes them roll two dice beforehand. The dice are rigged so that they will either roll a '3' or an '11,' and basically, the sentence is correlated to the dice roll. Even though the dice roll was completely random, the judges who rolled a higher number gave higher sentences. We are so out of touch with the real world. We are so lost, and it's actually quite terrifying.

Gross: More and more, researchers are saying that the conscious mind is a part of you that just makes up a story to explain all the things that other parts of you are deciding and trying to figure out.

Carey: "It is a child that sings itself to sleep / The mind, among the creatures that it makes."

Gross: Did you just make that up? [Laughs]

Carey: No, no. It's more Stevens. [Laughs]

Like Pauly, Rausch is a character that you've used throughout the series at critical junctures of the story, but unlike Pauly's tragic/comic relief, Rausch has almost ruled "The Unwritten" as Lady Justice -- doling our reward and punishment as she sees fit. Is she friend or foe?

Carey: Like Pauly, she's a character that we allow to drop in and drop out of the picture, but she's different because she's much more like Wilson and Pullman in that she's a manipulator. She's someone that sees the big picture and has her own agenda. She thinks that she can improve on God, improve on creation. There's no particular point in saving the world when you can create your own version of it. That's the freedom that the young Leviathan offer, potentially. I like writing her because she's a very ambivalent character. Where Pullman is almost entirely evil, certainly in the way that he interacts with the other characters, Rausch -- as far as she is concerned -- is doing the right thing. She has no interest in whether anyone else survives or not.

Gross: When we're all done with this, we should have a conversation about who is really the villain. [Laughs] Because I'm not 100 percent certain who it's going to be! [Laughs] When Mike says Pullman is almost entirely evil, in other ways, I see him as 100 percent victim. But we'll have more to say on that when we're all done.

Carey: The two things are not incompatible.

Gross: The biggest villain might be Rausch or Wilson.

Carey: They're certainly all candidates.

Or maybe it's Tom. He was pretty quick to give Rausch his own blood to bring her wooden children to life, as long as he moved his own story along.

Carey: Yes. That was a very sort of Faustian bargain. We will be returning to that story in #6. There is a lot more to be told about that deal.

I love Tom, Savoy and Lizzie, but the characters I really love are Pauly, Rausch and Pullman. I'm not sure what that says about me, that I love all of these enfants terrible. In "Apocalypse," Pullman is poisoning entire genres, which is creating a masterful monster mash-up of everything from Shakespearean drama to "The War of the Worlds." Let's play Pullman. If you could kill one genre of fiction, which would you kill?

Carey: [Laughs] I would have to go for romance.

Gross: I don't know. I guess books like the "Twilight" series can disappear.

This next arc is subtitled "The Fisher King," after a character from Arthurian legend who is charged with protecting the Holy Grail. What role has religion played in "The Unwritten?"

Gross: I think religion is a big deal for us. But I'm not sure how much I can say about its role just yet.

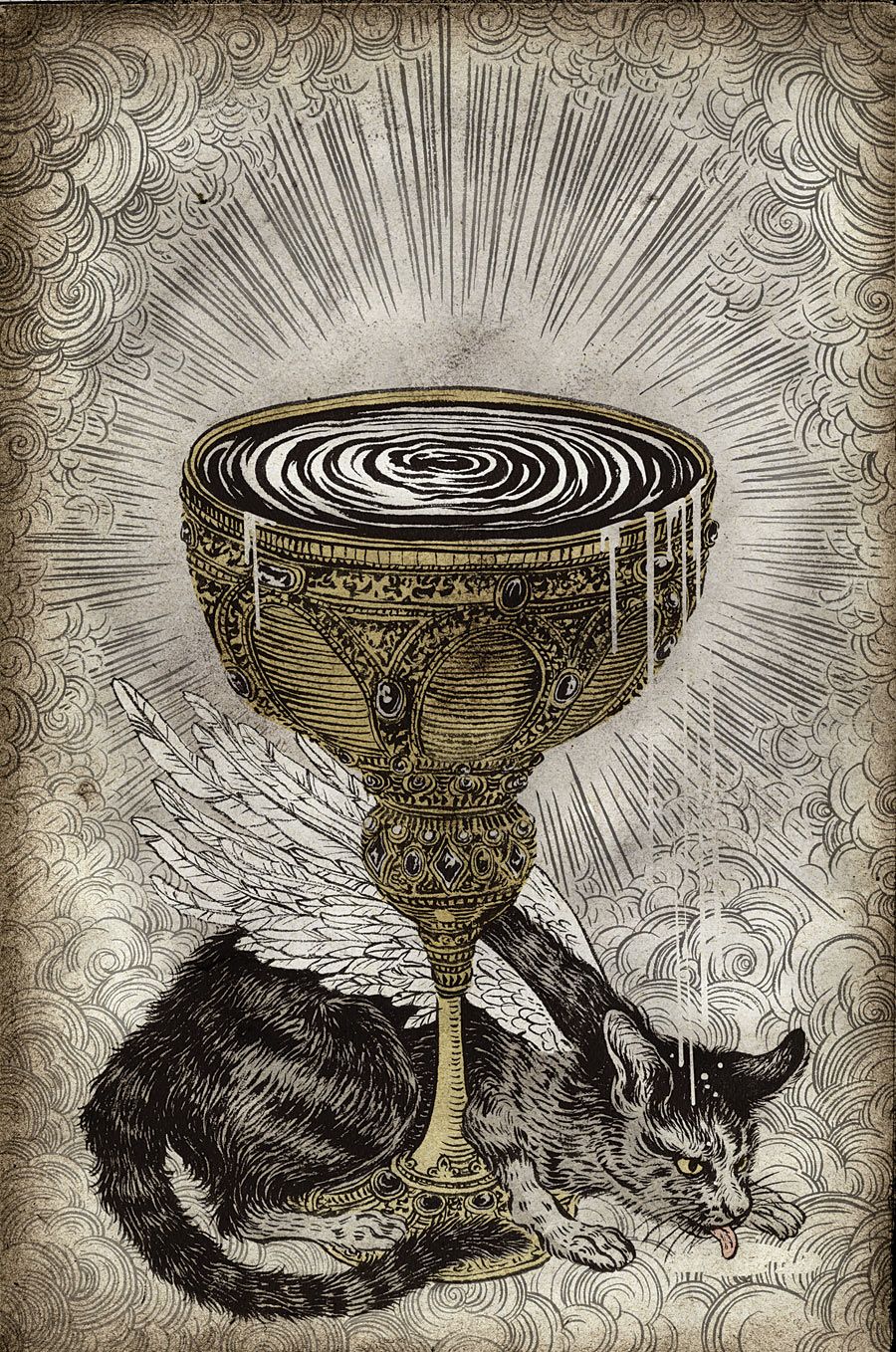

Carey: In the Holy Grail arc, we are bringing together Christian iconography with much earlier iconography from the very first human civilizations like Sumeria, and what we're basically suggesting is that belief is a force that has shaped the human spirit and shaped our perception in very lasting ways. The Grail is one of the side effects of that, because the Grail is not just the Grail. The Grail is other things too -- at least two other things.

Gross: And maybe more. [Laughs] The Grail reminds me of the way we used whales in the "Leviathan" arc. I equate the two. The Grail is an objectification of Leviathan.

The solicitation for "The Unwritten: Apocalypse" #8 teases Tom's hunt for a maanim. Is that the Holy Grail?

Carey: The Grail and the maanim are two aspects of the same thing, and there are other aspects that we'll also be playing with. All of this gets explicitly explained in #6, but there are some surprises, as well, after that.

Might those surprises include Armitage, as he's a character that we've seen very little lately? I sense he still has more story to tell.

Carey: I think you can very legitimately compare Armitage with Pauly, because he's a character that's been played with, manipulated and moved around like a counter. He played an important role in the "Wound" arc, and the thing that sent him to Australia in the first place was a message in a book. He picks up a book after the "War of Words" arc, and there is a personal image for him that just says "Brisbane, Australia," which he follows and goes out there and a lot of things happen to him. There are consequences, but we don't know yet who or what is manipulating him; we're about to find out in the next arc.

Does "The Fisher King" roll right into the final arc?

Carey: There is going to be one more stand-alone, which is #9, and then we get the final arc.

And then you're done. Working on these last few issues, do you have any regrets that you stopped too soon?

Gross: We've still got some stories on the table that we could have told, but it's like that with any series you do. But there is always the possibility that we can come back with more Tommy Taylor graphic novels too.

Carey: It's funny because given the title of the book is "The Unwritten," I always feel like that when you get past the midpoint of the story and you're closing in on the climax, every single issue you write is un-writing two or three other issues. There are pathways that you don't take, there are stories that you don't tell and sometimes it's almost like a phantom limb syndrome. You're very aware of those stories that never were.

"The Unwritten: Apocalypse" #6 by Mike Carey and Peter Gross is on sale now.