Writer Mark Gruenwald's theories about superhero rogues galleries helped transform Captain America's villains for decades to come.

Knowledge Waits is a feature where I just share some bit of comic book history that interests me.

REMARKS FROM MARK

Well before he was ever working as a comic book professional editor and writer, Mark Gruenwald was already one of the most thoughtful and observant writer in the world of comic book fanzines. Gruenwald edited, designed and did much of the writing for his own fanzine, Omniverse, which was dedicated to the exploration of continuity in comic books.

Gruenwald also wrote a series of articles for DC's in-house magazine, The Amazing World of DC Comics. As you can see from the Omnivese introduction, Gruenwald was not just a thoughtful, interesting guy, but he was a thoughtful, interesting guy who had pretty hard and fast opinions about things and how things should be done.

That attitude followed him to Marvel Comics as he became an assistant editor in the late 1970s and soon moved on to becoming a full-time editor, while working as a writer for Marvel, as well. Eventually, Gruenwald became the ongoing writer for Captain America while being the editor on Iron Man, Avengers and West Coast Avengers. Gruenwald then launched a monthly column that would appear in each of the titles that he edited titled "Mark's Remarks," where he would expound on various theories he had about comic books.

One of these theories he clearly implemented himself in the pages of Captain America and it had a lasting impact on the series.

THE ONE-VILLAIN-A-MONTH THEORY

In comic books cover-dated November 1986 (Avengers #273, West Coast Avengers #14 and Iron Man #212), Gruenwald's column delved into one of his theories about superheroes, specifically that they exist in comparison to their villains, and thus every superhero needs a good rogues gallery. He further explains how many regular villains each hero should have in a perfect world...

You don't get to be an editor for almost five years (and an assistant ed for four before that) without developing some sort of editorial philosophy about what you're doing. Much of what we're doing here at Marvel is heroic fiction. So here's my philosophy (or at least part of it) about heroes. A hero is heroic in direct proportion to the villainy of villains s/he confronts and triumphs against. Sounds simple and obvious enough, doesn't it? Who wouldn't pit his/her hero or heroes against as powerful and as evil a villain as possible in order to test the hero's mettle? Yet, certain heroes have managed to acquire "better" regular opponents to clash with than others. A "good" villain should a) have a clear motivation for his/her villainy, b) a credible background to foster that motivation, c) an effective superhuman power or gimmick to help him/her accomplish his/her goals, d) a good name and costume. A "great" villain should have all of the above plus a) a complex (not complicated) personality, and b) a good track record of how many times s/he succeeded in accomplishing his/her goals, or at least how difficult it was for a hero to thwart them.

So how many "good" and "great" villains can you think of? Does ever hero who has his/her own series have at least twelve of them? If not, says this editor, the writer will have to repeat him/herself a lot-- or resort to "bad" villains (those who don't fit the above criteria). That's why I'm on a campaign to get my writers to come up with new villains, at least every third storyline or so. That way, there will be new blood to replenish the tired old blood of villains who have lost one too many times to be taken seriously.

A hero who has it easy cannot prove his heroism. On the other hand, a villain who has it easy can prove his villainy. Villains need victims not heroes. A hero may only be as good as the toughest opponent s/he has faced. To make our heroes better, we've got to have better villains.

Captain America, when Gruenwald took over the series, mostly had, in terms of recurring villains, the Red Skull, of course, then maybe Viper/Madame Hydra and Baron Zemo, to a certain extent. Very soon into his run, Gruenwald introduced Madcap, who was a bit less of a villain and more of a wild card period, but he was at least an antagonist. Gruenwald also introduced the comedic villain, the Armadillo.

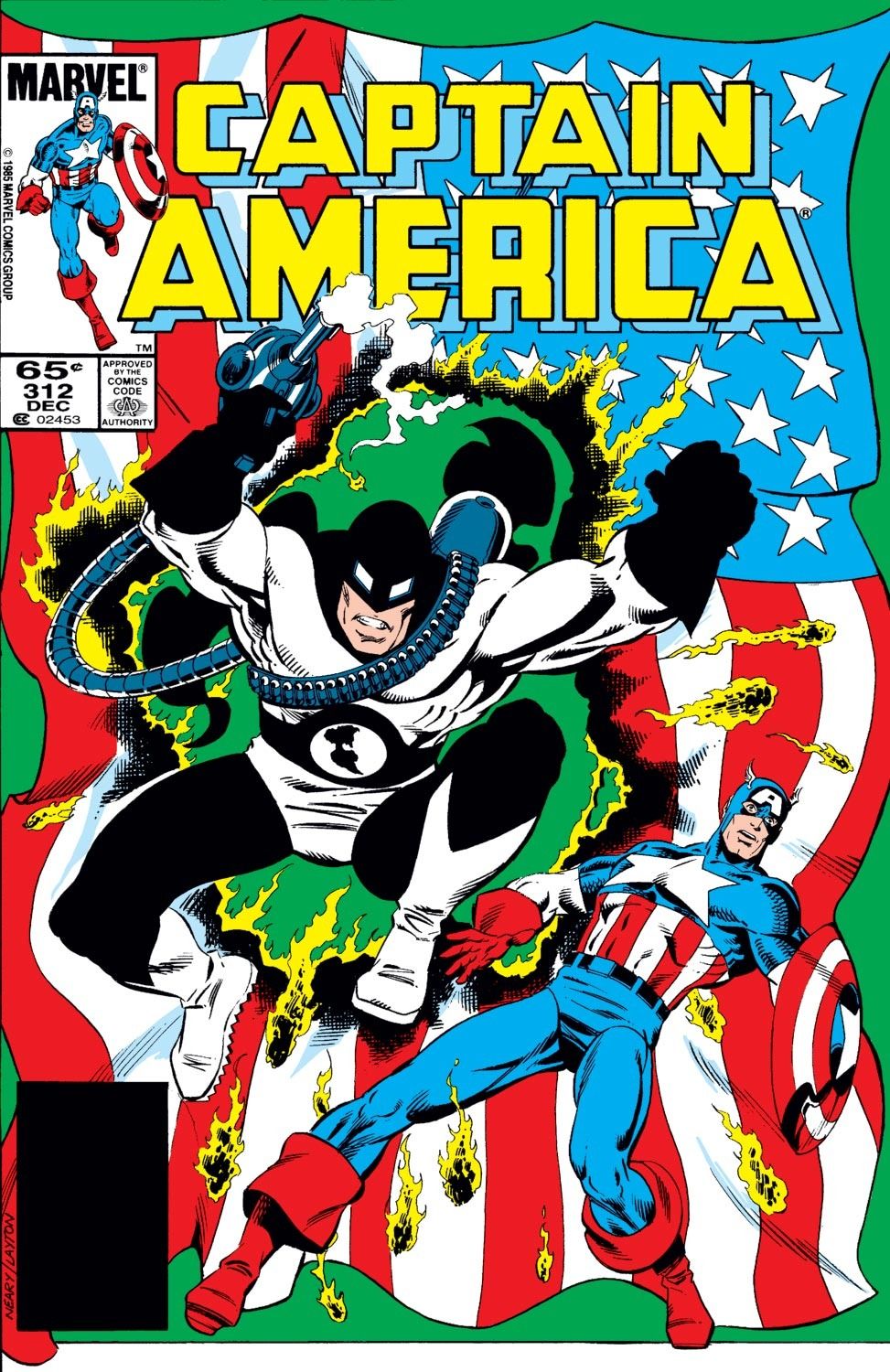

Then Gruenwald introduced the anarchist villain, the Flag-Smasher, who has had an impactful legacy...

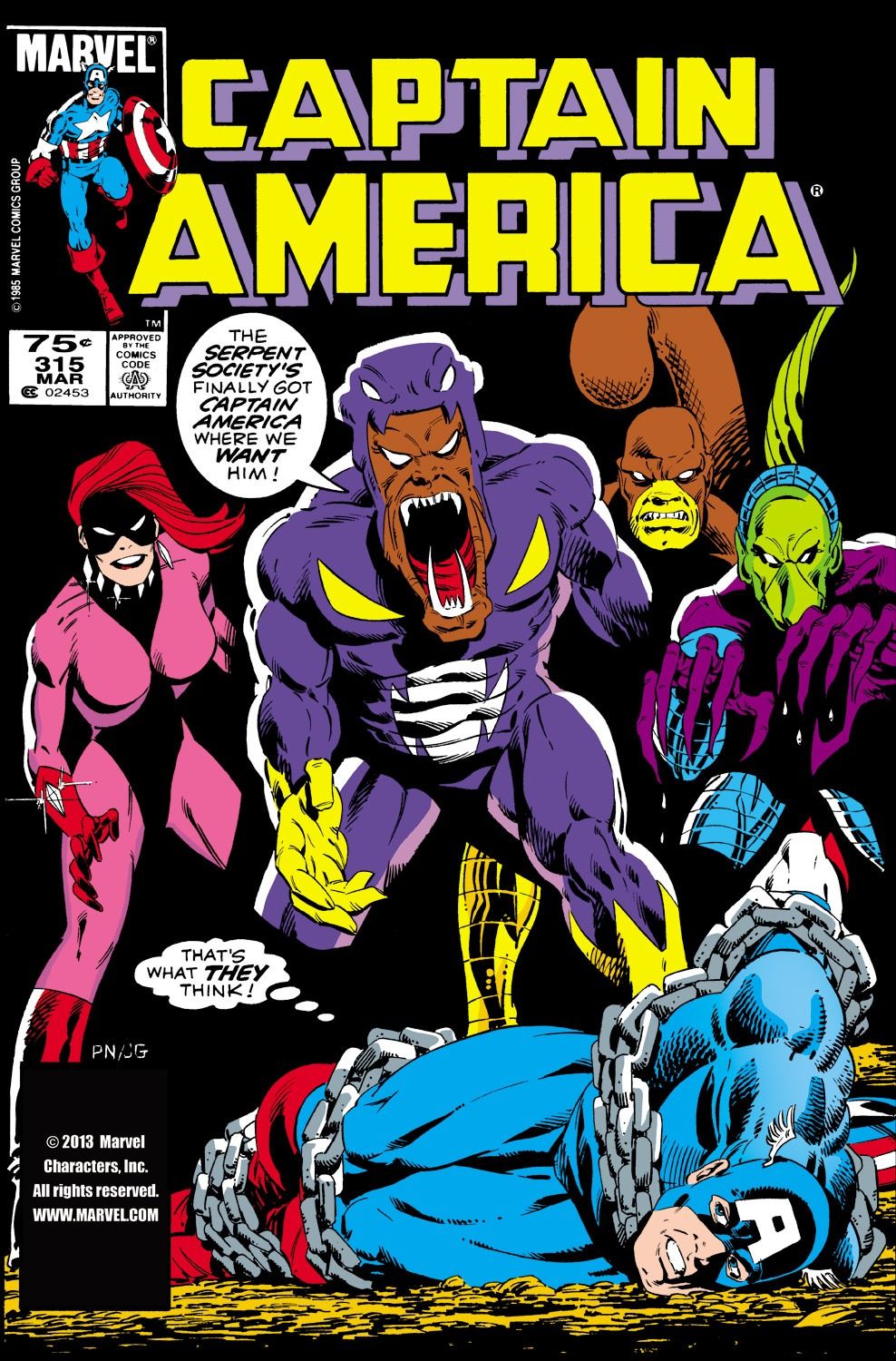

That was quickly followed by the Serpent Society, who played a major role in Gruenwald's run, especially as one of the members of the team, Diamondback, eventually fell in love with Captain America and decided to reform and become a superhero (her attempts at reformation did not exactly go smoothly)....

Gruenwald then introduced the Super-Patriot, John Walker, who would famously later take over as Captain America when Steve Rogers lost the title of Captain America as part of a confrontation with the government. When Steve returned to the title, Walker continued as a new hero known as U.S. Agent.

Other new antagonists introduced during this period varied from relatively successful (the Scourge) and fairly forgettable (the Slug).

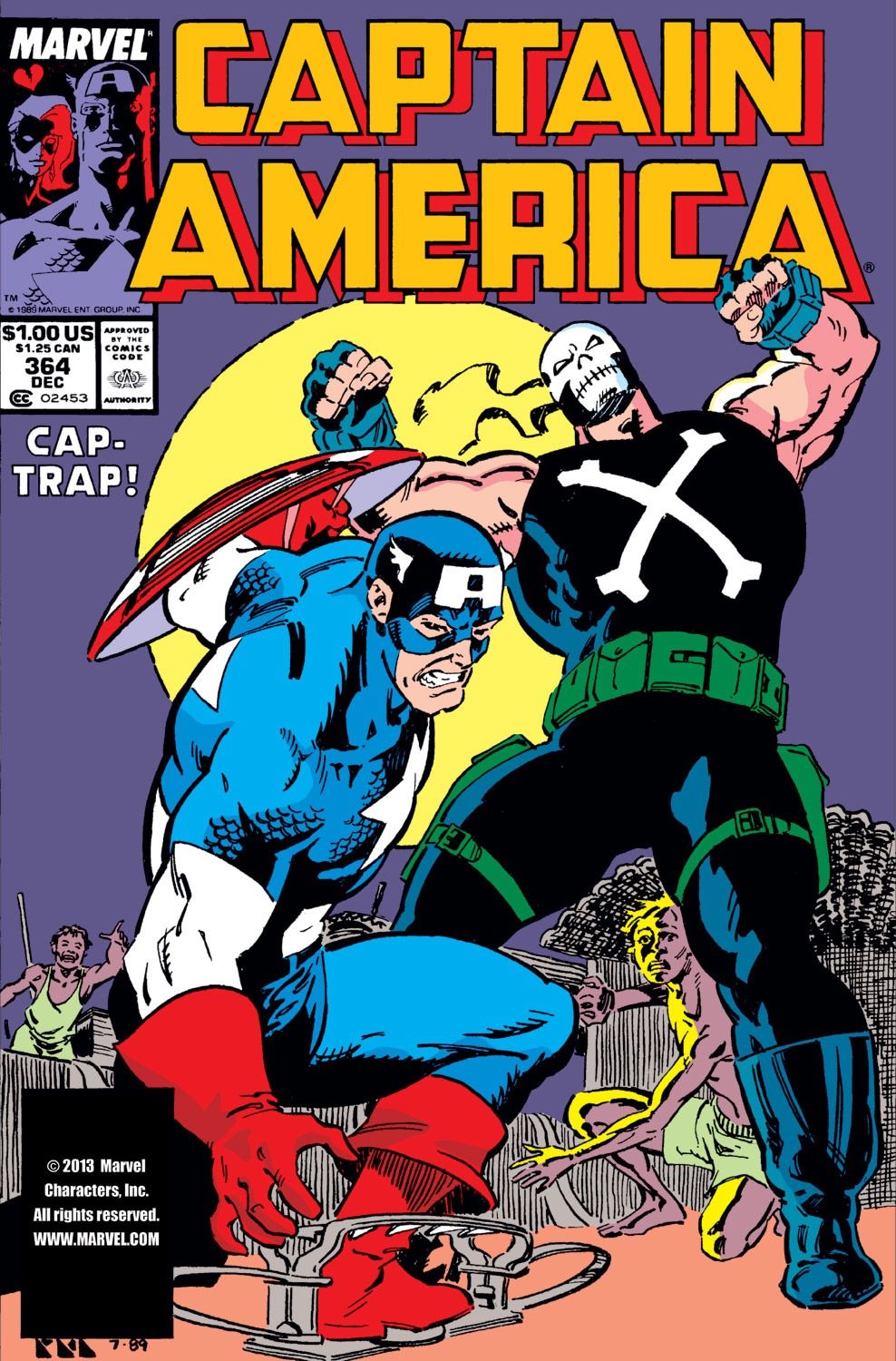

After Steve returned to the Captain America title, Gruenwald introduced one of the most successful additions to Cap's Rogues Gallery at the time, which was the Red Skull associate known as Crossbones...

Gruenwald kept creating new characters for as long as he was on the series, but his later creation had much less of an impact, like Superia, obsessed with creating a world ruled by women.

While Gruenwald perhaps did not quite get as far as to give Captain America a great villain every month, he certainly left Cap with a lot more strong villains than Cap had when Gruenwald started on the series.

If anyone has an idea for an interesting piece of comic book history, drop me a line at brianc@cbr.com!