Calling in the Firemen on Deadline

They're the firemen, the deadline savers. They're the artists who are called in to help out on a book that fallen behind deadline for one reason or another. You see their work all the time, because frankly the deadline grind on monthly comics is brutal on artists. There are very few artists who are built to keep up with the rigors of a contemporary issue, month in and month out. Maintaining a monthly schedule often requires an artist to come in and bail when the Good Ship Deadline is taking on water, and in danger of sinking.

It's a necessary job, and to be sure, most artists are glad for the work. But it also can lead to an artist being typecast as a fireman, someone who rarely gets asked for their best work, but far more often for their fastest work. Which in turn can lead to the impression of the artist being... well, just okay. Readers ultimately don't know the deadline demands under which an artist works, they only see the finished product, and make judgments based on that.

I saw it happen to artist Igor Kordey, who worked with me on the "Batman-Tarzan" crossover. Igor eventually found himself working on "X-Men," trying to pull the title out of habitual deadline doom. He often had to pencil and ink issues in two weeks. He told me he once penciled and inked an entire 22-page issue in about a week, because that's what was asked of him. Audience reaction was mixed at best. When the "X-Men" assignment ended, Igor found his artistic reputation had suffered due to what were perceived as slapdash issues. Disillusioned to be thought of as damaged goods, he returned to the European market, where he's done the vast majority of his work ever since.

Much the same happened to my "Silver Surfer" partner Ron Lim, the first artist I ever worked with. The sales boom of the 1990s meant publishers were scrambling to put as many titles as possible on the stands. A guy like Ron, who was fast and supremely dependable, got pulled into a myriad of assignments beyond "Surfer" and "Captain America," including all the "Infinity" books, "X-Men 2099," "Spider-Man Unlimited," "Venom" and a lot more.

I remember having a conversation with Ron during which he told me that he didn't want to be doing that much work, he'd rather just draw "Surfer" and the "Infinity" issues when they came up. He didn't want to be working so fast that he wasn't happy with the pages. But when editors would call, asking for deadline help, he didn't want to disappoint them. He was the guy who couldn't say no, so he blasted out the work as fast as he could to meet the schedule demands.

When the boom was over, Ron found his assignments dried up, in large part, because many editors viewed him as a guy who hacked out his work. Catch-22, anyone?

Another artist who was seen as a fireman was Welsh artist Anthony Williams. I worked with "Ant" a few times on "Green Lantern" issues, always when we needed a deadline assist. Ant drew damn near everything in the mid- to late '90s, but eventually walked away from the industry. I talked to Ant about his experiences as a fireman, and how it affected him and his career.

Full disclosure: Ant and I, along with Andy Lanning, are working together on projects for a company called Magic Leap. Exactly what Magic Leap is... well, we can't really talk about that yet. But I personally can tell you it's the most exciting venture in which I've ever been involved.

Ron Marz: You and I worked together on a few things, like "Green Lantern," but give me a sense of the rest of your credits.

Anthony Williams: I started in the UK, drawing titles such as "Ghostbusters." After a couple of years, I moved onto "Judge Dredd" and a number of series for "2000 AD," and like many other UK-based artists, this helped to open the door to the US (along with lobbying from my good friend Andy Lanning). After a few single-issue jobs I moved onto series for both Marvel and DC including "Hokum and Hex," "Fate," "Scare Tactics" and "Marvel Action Hour." These books gave me an opportunity to polish my craft some more, and I began to steadily work up the chain, moving onto fill-in opportunities on books like "Impulse" and "Iron Man." I had a really satisfying three-issue story arc in "Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight" during this period. From there I progressed to single and double issues of big-name books such as "Superman" and various X-books. The problems then began, because I was always jumping onto a late book. A big-name book for sure, but late nonetheless, and with a deadline to match.

Obviously that's a diverse array of credits, without a real "signature" credit. Do you feel like that contributed to you bouncing from project to project?

With hindsight I realize there was a moment when I was hot and in demand by editors from both Marvel and DC. If I had the wisdom then that I have now, I would have had the courage and common sense to turn work down, lobby for a decent run on a big-name book, and deliver what I knew I was capable of.

I feel like you were absolutely seen as a "deadline-saver" guy -- someone an editor could turn to in a pinch to pull their asses out the fire when a book was late. Sometimes a whole issue, sometimes part of an issue, but always under the deadline gun. Work is work, but obviously that's not ideal. Did you have that sense while it was happening?

Initially, I was flattered by the fact I was in demand and I assumed that if I helped out "editor X," then I would get an opportunity to shine later. However, the reality was I bounced from one rush job to another with barely time to think. At its peak, I was drawing three books a month. I well remember I drew a four-issue Batman mini that the original artist had bailed on. It was hideously late, and I had to pencil the whole thing in a little over three weeks. And if memory serves, I had another book I was committed to as well. That was my lowest ebb. I recall standing in a theme park in the middle of this deadline nightmare, having promised this trip to my long-suffering wife and three young children many weeks before, and all I could feel was guilt and rising panic that I wasn't working on the book.

Not much chance to do your best work under those conditions, huh?

I always tried, but inevitably I would often have to just sit down, switch on the auto pilot, and draw, draw, draw. I'm pretty quick naturally, and I could comfortably pencil a couple of pages a day with no distractions. But there were times when I was penciling four pages a day, seven days a week.

The unfairness of it, to me at least, was that you and other "firemen" were not often rewarded with a higher-profile or regular gig. In part, I think, because if you were on regular gig, you wouldn't be available to pull someone's ass out of the deadline fire.

I didn't consider that at the time. I lurched from job to job, and barely had a chance to stand back and realize what was going on. With hindsight, I think you may be right to a degree. I think it's also worth stressing that I was as much to blame as anyone for being in that position. I am grateful to the editors who gave me the opportunity to work on a number of high-profile books, and I regret sometimes not giving my best because I was over-committed and too eager to please.

You eventually turned away from making comics your complete vocation. Why did you make that decision?

I was burned out. My work suffered as a result. I lost the love of the job. I could feel my worth and value as an artist had drained away to the point where I was having to make uncomfortable phone calls to ask for work, seldom with positive results. I managed to pick up a little work on licensed comics such as "Johnny Bravo" and "The Flintstones," and then a little more and then a little more. The superhero work, the stuff I wanted to do all my life, was gone. Effectively I was old news at the age of 36.

Do you feel like you made the right move to step away?

I'm very lucky in that I've always had a burning ambition to do more than be just a jobbing artist. I realized that I was not likely to rise to the top of the comic world, not only because I had misjudged how to play my career, but also because the comic world has some astonishing talent working in it, and I was lacking that last ten percent at the time.

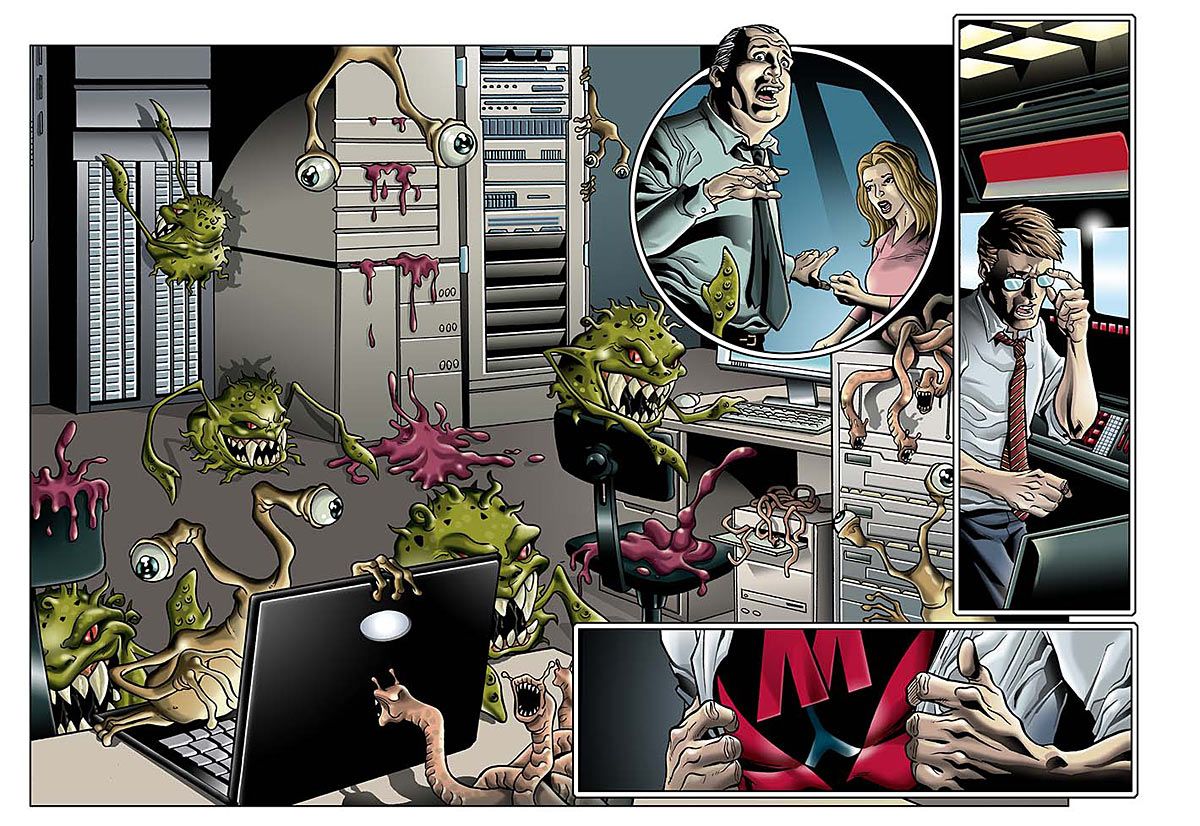

I did and still do have a facility to draw in many styles, and I parlayed this into setting up a studio, Comic Stripper Ltd, that looked for all intents and purposes to have a number of illustrators on its books. In reality... just me. I looked for work drawing comics and comic-style illustration for the bigger world. The work could sometimes be mind-numbingly dull. For example, a comic book to help sales people flog insurance. But slowly I built a reputation and the work got more prestigious. I built up an international client list, and reached the point where I was swamped with work and took on my first illustrator, and then another, and the business just kept growing. The studio has created artwork for huge international clients, and we've had the opportunity to create whole advertising and marketing campaigns from the ground up.

I know you've never lost your affection for comics, and that you're working on a comics project right now... though we can't say what it is yet. Having seen some of the pages, I think it's the best work you've done, just beautiful stuff. Do you feel like you're finally getting a chance to put your best foot forward?

Well, as you know, Ron, in the last couple of years my working life has taken a dramatic and incredibly exciting turn. I wish I could talk more about what I'm involved in, and the opportunities that I now have. What I can say is, as part of a much bigger project, I'm drawing a comic book. And best of all, I have the time to enjoy it.

I'm a bit rusty, and it's a necessarily tortuous experience at times trying to pull the best out of myself, but I'm getting there. I'm looking forward to having a comic book on the shelves again in the near future.

Ron Marz has been writing comics for two decades, and thinks it's pretty much the best job ever. His current work includes "Witchblade" and the graphic novel series "Ravine" for Top Cow, "The Protectors" for Athlitacomics, his creator-owned title, "Shinku," for Image, and Sunday-style strips "The Mucker" and "Korak" for Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. Follow him on Twitter (@ronmarz) and his website, www.ronmarz.com.