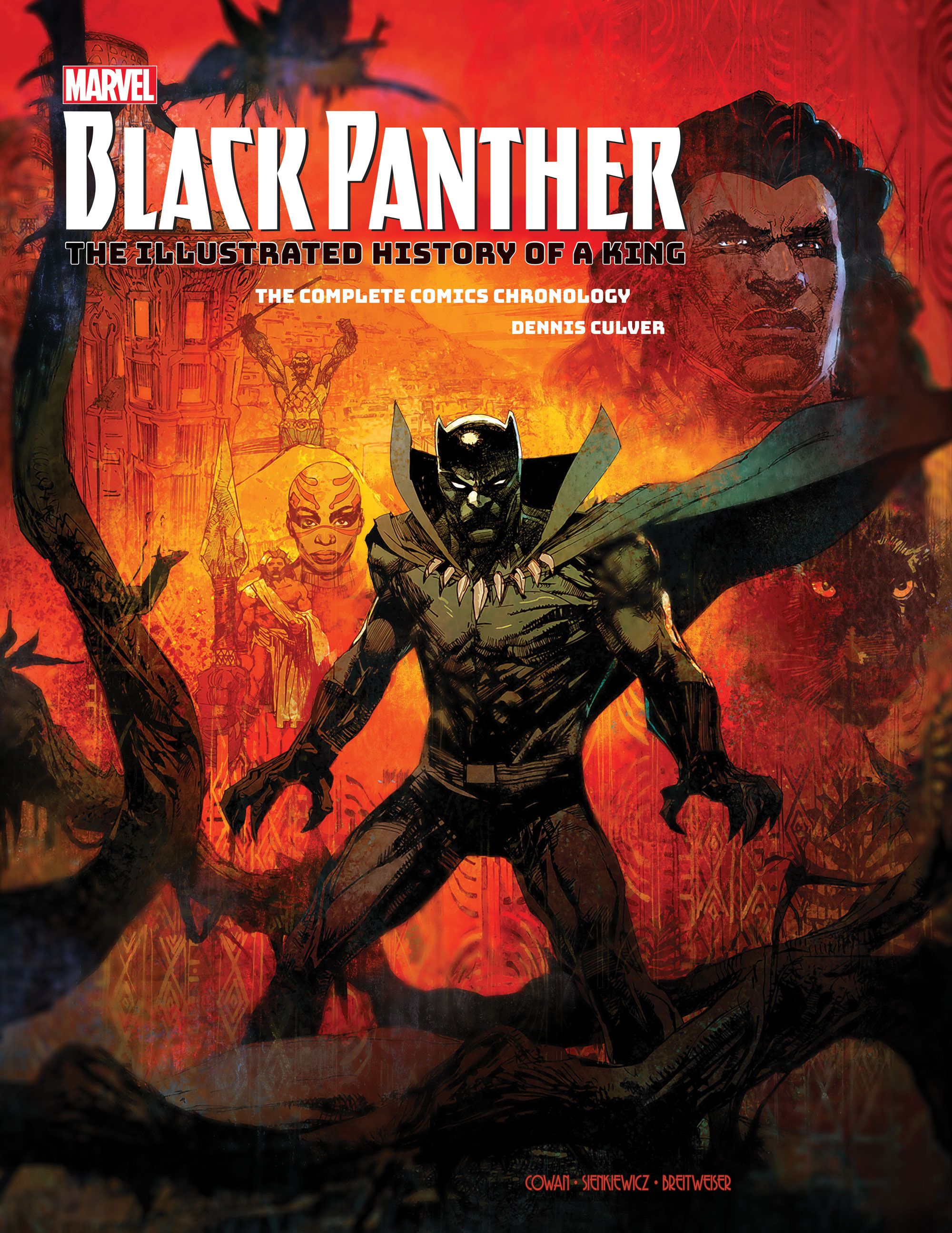

Marvel’s Black Panther: The Illustrated History of a King

- WRITER

- Dennis Culver

- Artist

- Various

- Cover Artist

- Bill Sienkiewicz, Denys Cowan

- Publisher

- Insight Editions

- Price

- 45.00

- Release Date

- 2018-01-09

CBR presents a special look at Insight Editions' hardcover book Marvel’s Black Panther: The Illustrated History of a King, written by Dennis Culver and available now. The section previewed below spotlights the Marvel Knights era of Black Panther, when writer Christopher Priest and artist Mark Texeira launched an acclaimed take on the character in 1998. Text from the section follows.

Solicitation text:

From his first appearance in Fantastic Four #52 (1966) to his current New York Times-bestselling solo series, the King of Wakanda has been a force to be reckoned with on the page and now, on the silver screen. A veteran Avenger and a member of the Illuminati, T'Challa's evolution from being a Jack Kirby and Stan Lee creation, to inspiring his own character-led film for Marvel Studios, to serving as a literal voice of the people and the state of race relations in twenty-first-century America has been legendary. As the first black superhero in mainstream American comics, debuting years before other industry heavy hitters like the Falcon, Luke Cage, and John Stewart (Green Lantern), Black Panther is a seminal note in pop culture history. This deluxe hardcover book not only covers the history and creation of the character but also features exclusive concept art, layout and sketch art, and interviews with key artists and writers from Black Panther's robust archives.

RELATED: Rise of the Black Panther Picks Up on A Marvel Legacy #1 Plot Point

Marvel’s The Black Panther: The Illustrated History of a King

Chapter 5: Marvel Knight

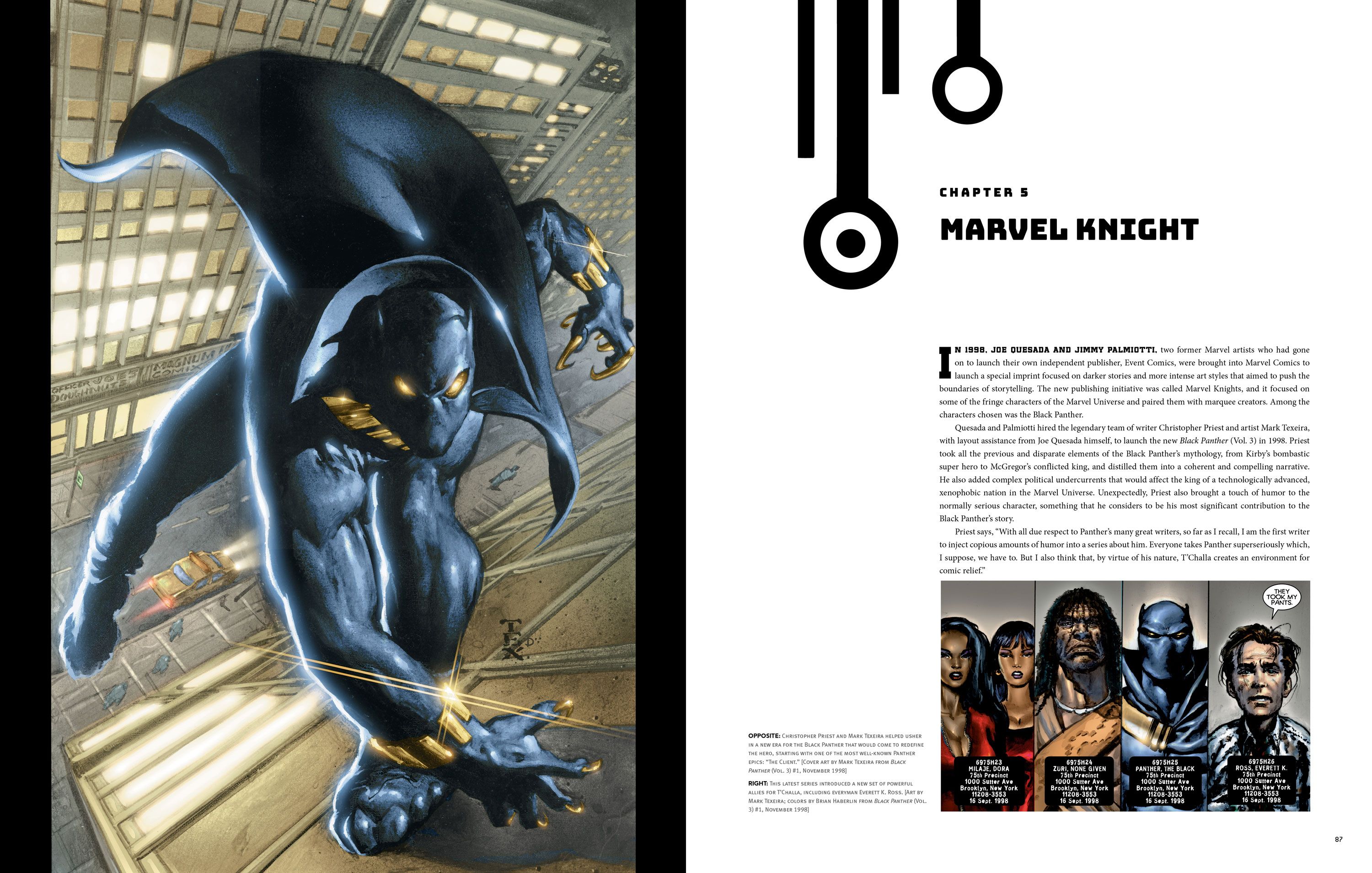

IN 1998, JOE QUESADA AND JIMMY PALMIOTTI, two former Marvel artists who had gone on to launch their own independent publisher, Event Comics, were brought into Marvel Comics to launch a special imprint focused on darker stories and more intense art styles that aimed to push the boundaries of storytelling. The new publishing initiative was called Marvel Knights, and it focused on some of the fringe characters of the Marvel Universe and paired them with marquee creators. Among the characters chosen was the Black Panther.

Quesada and Palmiotti hired the legendary team of writer Christopher Priest and artist Mark Texeira, with layout assistance from Joe Quesada himself, to launch the new Black Panther (Vol. 3) in 1998. Priest took all the previous and disparate elements of the Black Panther’s mythology, from Kirby’s bombastic super hero to McGregor’s conflicted king, and distilled them into a coherent and compelling narrative. He also added complex political undercurrents that would affect the king of a technologically advanced, xenophobic nation in the Marvel Universe. Unexpectedly, Priest also brought a touch of humor to the normally serious character, something that he considers to be his most significant contribution to the Black Panther’s story.

Priest says, “With all due respect to Panther’s many great writers, so far as I recall, I am the first writer to inject copious amounts of humor into a series about him. Everyone takes Panther superseriously which, I suppose, we have to. But I also think that, by virtue of his nature, T’Challa creates an environment for comic relief.”

Texeira’s lush painted art set the tone for the rest of the series, creating a distinct look and design for the Black Panther that would inspire the artists of subsequent arcs. The Black Panther, normally a character clad completely in black, now was adorned with golden Vibranium highlights on his costume as well as golden claws, which made him both more regal and more fearsome.

The first arc of the series, called “The Client,” introduces us to Everett K. Ross, a State Department employee tasked with escorting King T’Challa and his entourage while the monarch is in the United States. Priest says, “I believe my other major contribution was my interjecting an everyman—Everett K. Ross—into the series as the audience’s point-of-view character. Super hero comics have traditionally been created by white males for white males, which can be a difficult audience to whom to sell a black character. Joe Quesada, Jimmy Palmiotti’s, and my strategy was to overcome market resistance by having a character lend a voice to the typical fan resistance to black characters, exploding those stereotypes and presumptions through humor.”

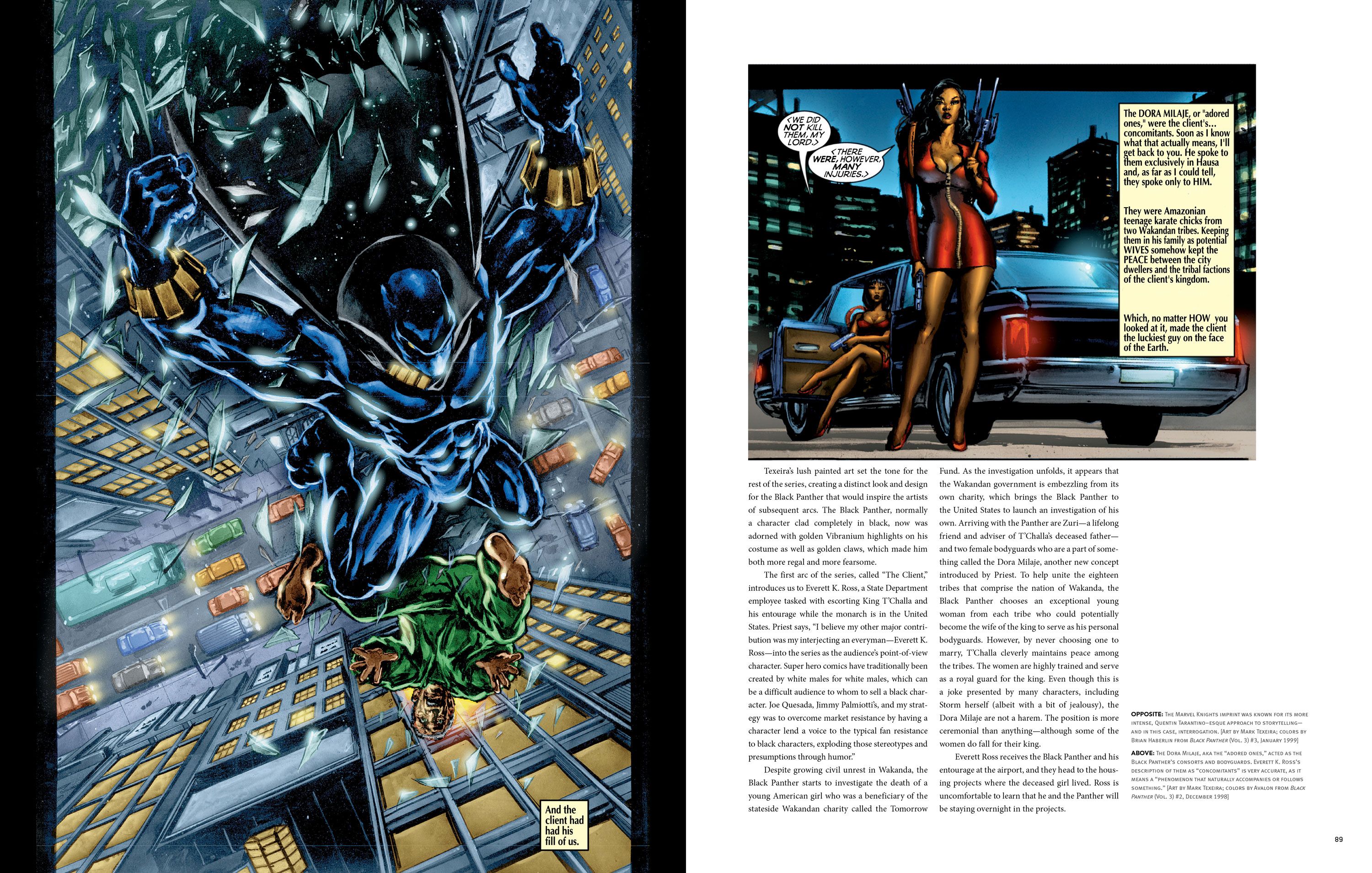

Despite growing civil unrest in Wakanda, the Black Panther starts to investigate the death of a young American girl who was a beneficiary of the stateside Wakandan charity called the Tomorrow Fund. As the investigation unfolds, it appears that the Wakandan government is embezzling from its own charity, which brings the Black Panther to the United States to launch an investigation of his own. Arriving with the Panther are Zuri—a lifelong friend and adviser of T’Challa’s deceased father—and two female bodyguards who are a part of something called the Dora Milaje, another new concept introduced by Priest. To help unite the eighteen tribes that comprise the nation of Wakanda, the Black Panther chooses an exceptional young woman from each tribe who could potentially become the wife of the king to serve as his personal bodyguards. However, by never choosing one to marry, T’Challa cleverly maintains peace among the tribes. The women are highly trained and serve as a royal guard for the king. Even though this is a joke presented by many characters, including Storm herself (albeit with a bit of jealousy), the Dora Milaje are not a harem. The position is more ceremonial than anything—although some of the women do fall for their king.

Everett Ross receives the Black Panther and his entourage at the airport, and they head to the housing projects where the deceased girl lived. Ross is uncomfortable to learn that he and the Panther will be staying overnight in the projects.

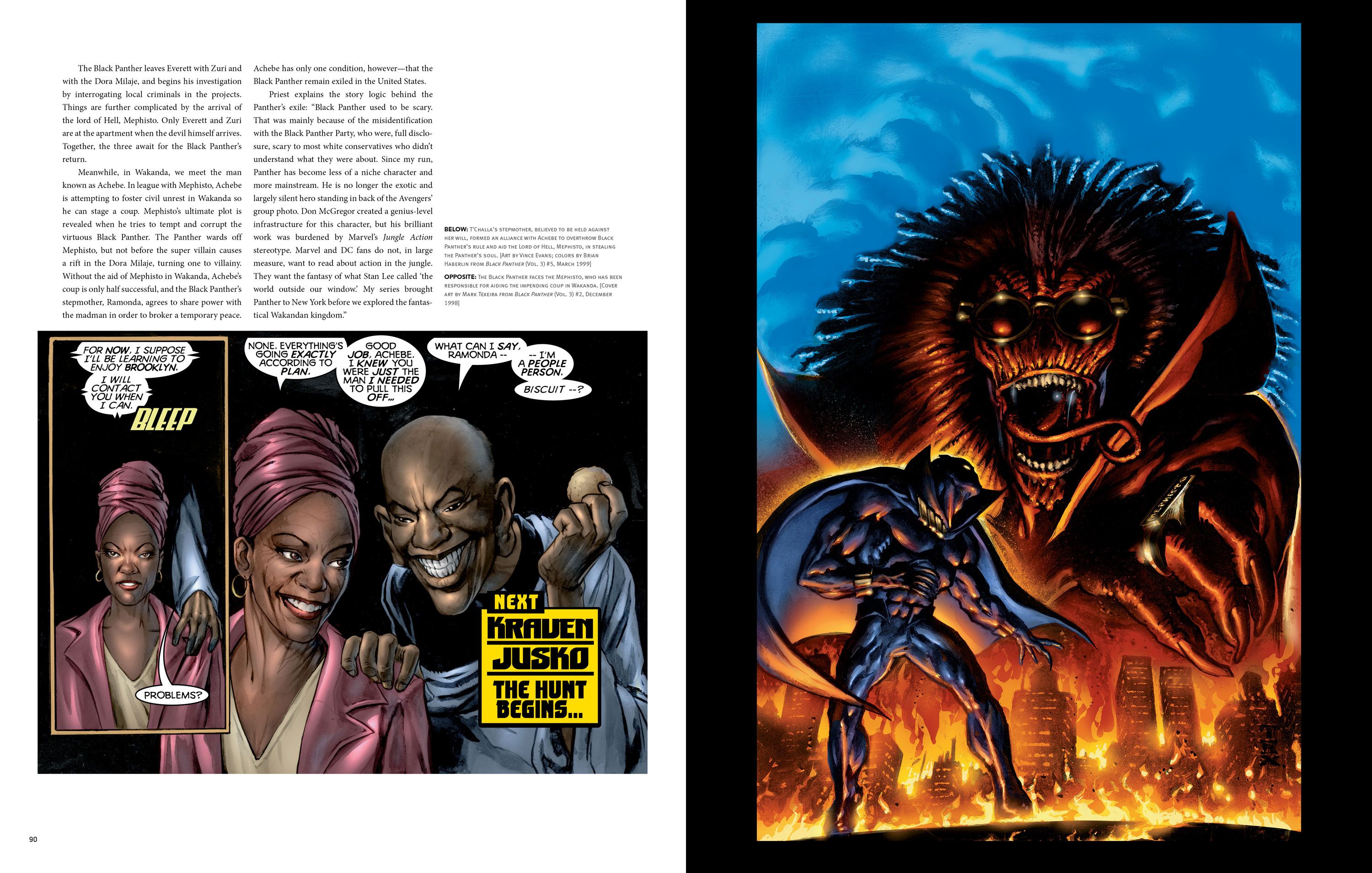

The Black Panther leaves Everett with Zuri and with the Dora Milaje, and begins his investigation by interrogating local criminals in the projects. Things are further complicated by the arrival of the lord of Hell, Mephisto. Only Everett and Zuri are at the apartment when the devil himself arrives. Together, the three await for the Black Panther’s return.

Meanwhile, in Wakanda, we meet the man known as Achebe. In league with Mephisto, Achebe is attempting to foster civil unrest in Wakanda so he can stage a coup. Mephisto’s ultimate plot is revealed when he tries to tempt and corrupt the virtuous Black Panther. The Panther wards off Mephisto, but not before the super villain causes a rift in the Dora Milaje, turning one to villainy. Without the aid of Mephisto in Wakanda, Achebe’s coup is only half successful, and the Black Panther’s stepmother, Ramonda, agrees to share power with the madman in order to broker a temporary peace. Achebe has only one condition, however—that the Black Panther remain exiled in the United States.

Priest explains the story logic behind the Panther’s exile: “Black Panther used to be scary. That was mainly because of the misidentification with the Black Panther Party, who were, full disclosure, scary to most white conservatives who didn’t understand what they were about. Since my run, Panther has become less of a niche character and more mainstream. He is no longer the exotic and largely silent hero standing in back of the Avengers’ group photo. Don McGregor created a genius-level infrastructure for this character, but his brilliant work was burdened by Marvel’s Jungle Action stereotype. Marvel and DC fans do not, in large measure, want to read about action in the jungle. They want the fantasy of what Stan Lee called ‘the world outside our window.’ My series brought Panther to New York before we explored the fantastical Wakandan kingdom.