In which Bill remembers his WordPress password…

I still buy an unhealthy amount of comics. By unhealthy, I mean it would be hazardous to my health if the pile of comics were to topple onto me. The problem is compounded by the fact that while I may be buying plenty of comics, I'm not reading very many of them. To wit, here is but a small sample of my "To Be Read" pile:

In an effort to make you, the reader, complicit in my illness, let's talk about a couple recent acquisitions.

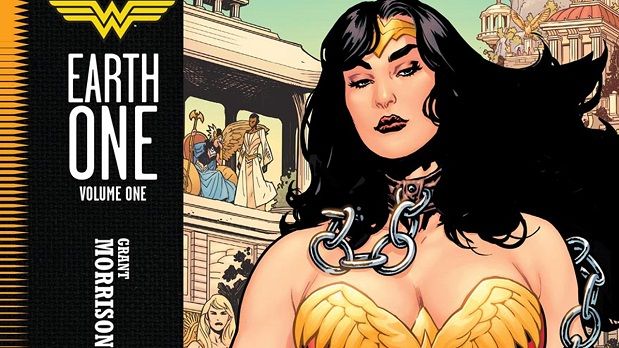

Wonder Woman: Earth One Art Art by Yanick Paquette, Story Art by Grant Morrison, Color Art by Nathan Fairbairn, Letter Art by Todd Klein.

When I was a little shaver, I would always play superhero. Batman, Spider-Man, Superman, the Hulk, probably ROM Spaceknight. And one day, I asked my mom permission to play Wonder Woman. Wonder Woman was a girl, girls were the other, and I needed to know it was okay to pretend, only for an afternoon, that I had an invisible jet and could deflect bullets with my wrists. There may have been some spinning around—Lynda Carter reruns were still on the air, after all.

There is, sadly, no spinning in Wonder Woman: Earth One. For a graphic novel made exclusively by white men, however, it makes a point to find an antithesis to the male action hero, and rebuild the character gynocentrically, embracing the very thing that made me so nervous as a kid. Prologue aside, maybe one or two panels could pass for “fight scenes,” but the majority of the time, Diana of the Amazons defuses the fights before they can begin, and refuses to play into the plot mechanics that normally lead to violence. The climax of the plot is resolved the same way as on the best show on television, Jane the Virgin—with honesty. Wonder Woman’s lasso of truth factors into both the character and story’s focus on this emotional honesty, and also thematically ties into Grant Morrison’s fascination with the sexual under—or over—tones of the very first Wonder Woman stories.

No “definitive” version of Wonder Woman has truly existed throughout the character’s 75-year history, and in recent years those fresh takes and revamps have only accelerated. Morrison returns the character to her Golden Age roots, embracing the kink of the original William Moulton Marston stories. The version of the character I was most previously familiar with was the virginal warrior demigoddess of the Post-Crisis era, but Morrison’s version takes the sexual subtext of the original stories and renders it as explicit text, with an LGBTQ and BDSM Diana who has a girlfriend and believes in submission as an act of love and strength.

With allies Beth (not Etta) Candy, a character who is fully comfortable with her plus-sized figure, but who unfortunately suffers a few too many fat jokes or jibes in the script, and Steve Trevor, who is now a black man familiar with the oppression our society is too readily capable of, Wonder Woman rebels against both the militant, isolationist feminists of Paradise Island and the militant, invasive forces of Man’s World.

I hate shortchanging the art, which is up to Yanick Paquette’s usual impeccable standards. His lays out pages and panels in inventive ways—much has already been said about his Grecian urn panels borders and the giant phallus that shows up when Steve Trevor washes ashore on Paradise Island. Panels take an orb or circular shape, as times the panel borders literally becoming the loops of the lasso of truth, or bending like the curves of the Wonder Woman logo (or bustier). Wonder Woman’s invisible jet resembles a Georgia O’Keefe sketch. The body language of the characters is important here—Beth’s confidence, Steve’s awe and bewilderment at various points, and most importantly, Diana’s strength even in submission.

There are several layers to this onion, and I haven’t touched on some of the more problematic elements, much of which stems from the changes to Wonder Woman’s origin and the opening rape/revenge scene which features Hercules’ violent domination of Hippolyta, followed by her retribution. It lends itself to the characterization set up for Diana’s mother, and acts as a hard contrast to the later rejection of violence we see from Diana, but it goes on a little too long and feels harsher than necessary for the overall tone of the book. The sequence lends credence to some of the harsher reactions the story has received, compounded by the fact that it immediate follows the cover shot of Wonder Woman in bondage.

Reviews of this one have been mixed, with writers often citing the same scenes/elements as positives or negatives. I fall somewhere in the middle. It's clear Morrison has done his research, and I believe the creators are very purposefully utilizing uncomfortable imagery and elements as a way to both empower the character and undermine the traditional male gaze of superhero storytelling. At the same time, they push back against Marston's concept of the "perfect world" of the Amazons, trying to use Diana as a representation of middle ground between the two opposing viewpoints. Subversion is the point, and I think the audience, no matter where they fall politically, is meant to be pushed out of their comfort zone. It's a fine line to walk, though, and it's totally understandable why opinions vary greatly here.

The Wonder Woman of this graphic novel bridges the gap between her respective worlds and shows us that assimilation is a two-way street: the one entering a new society adapts to its surroundings, but the surroundings also adapt to the immigrant over time. This Wonder Woman is a strong, peaceful, curious, adventurous, inclusive figure who transcends worlds, societies, sexualities. I’m not convinced DC published this book—I think it escaped.

So yes, Virgil, there is a Wonder Woman, and you can be her if you want.

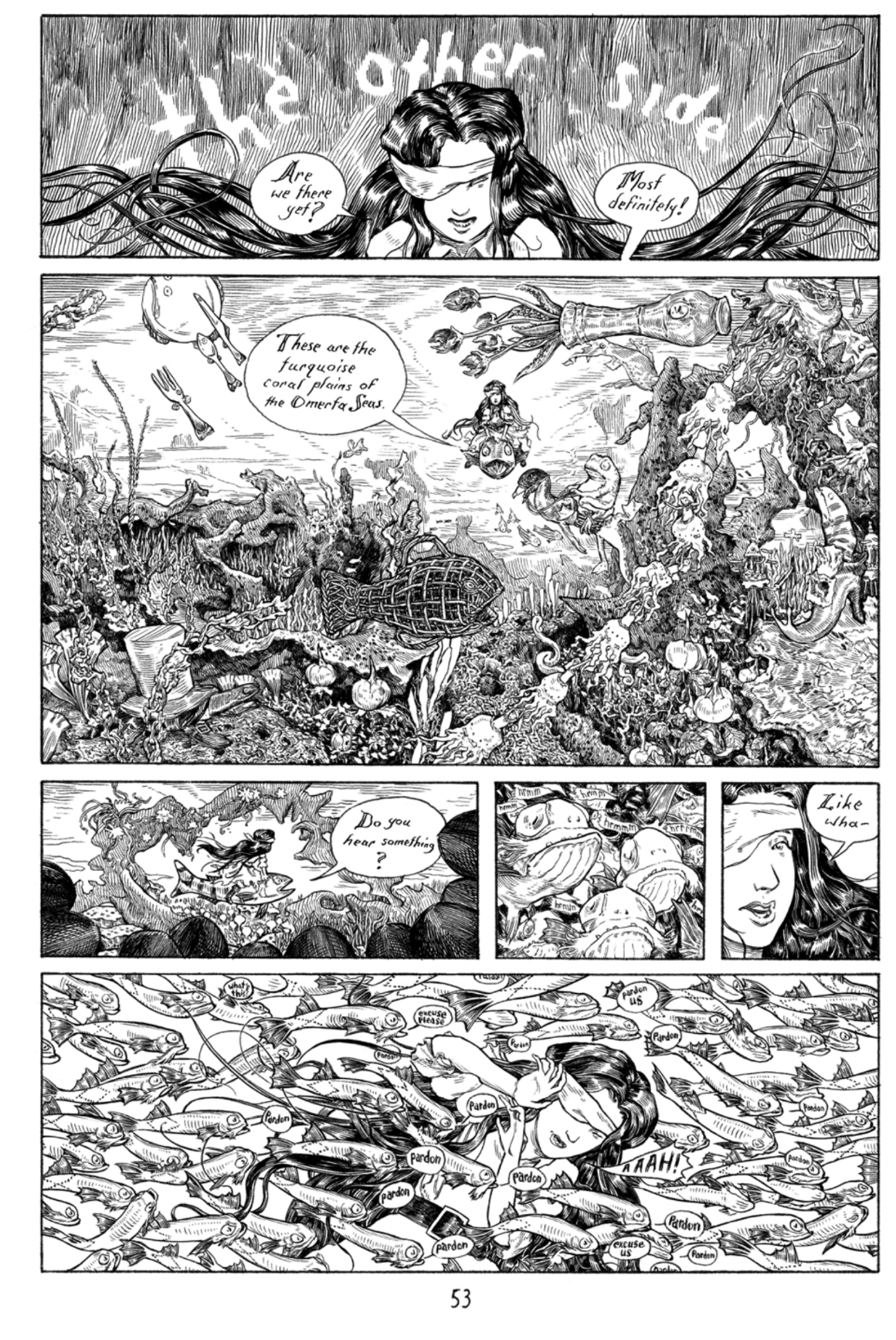

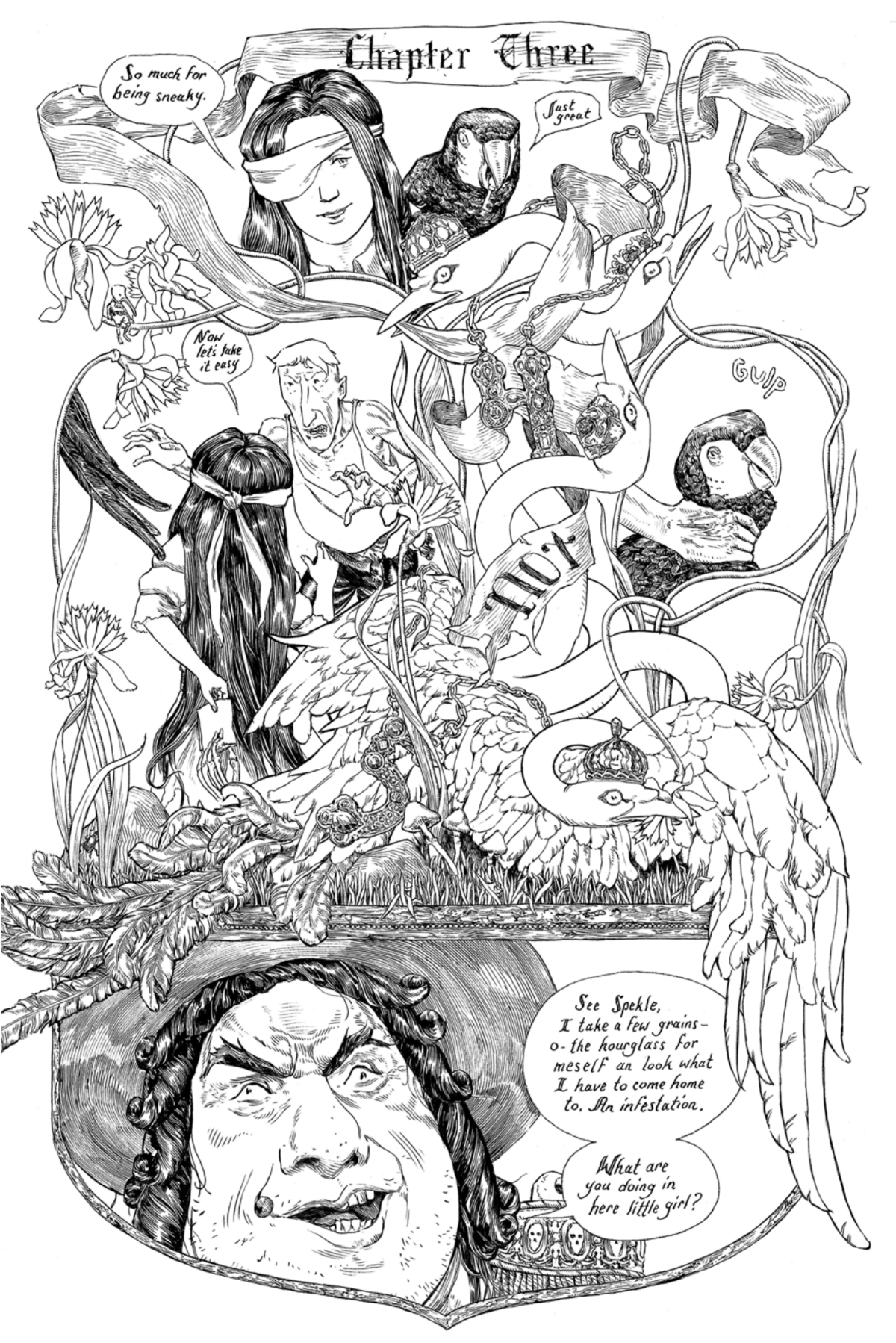

Cursed Pirate Girl Literally everything by Jeremy Bastian, published by Archaia/Boom!

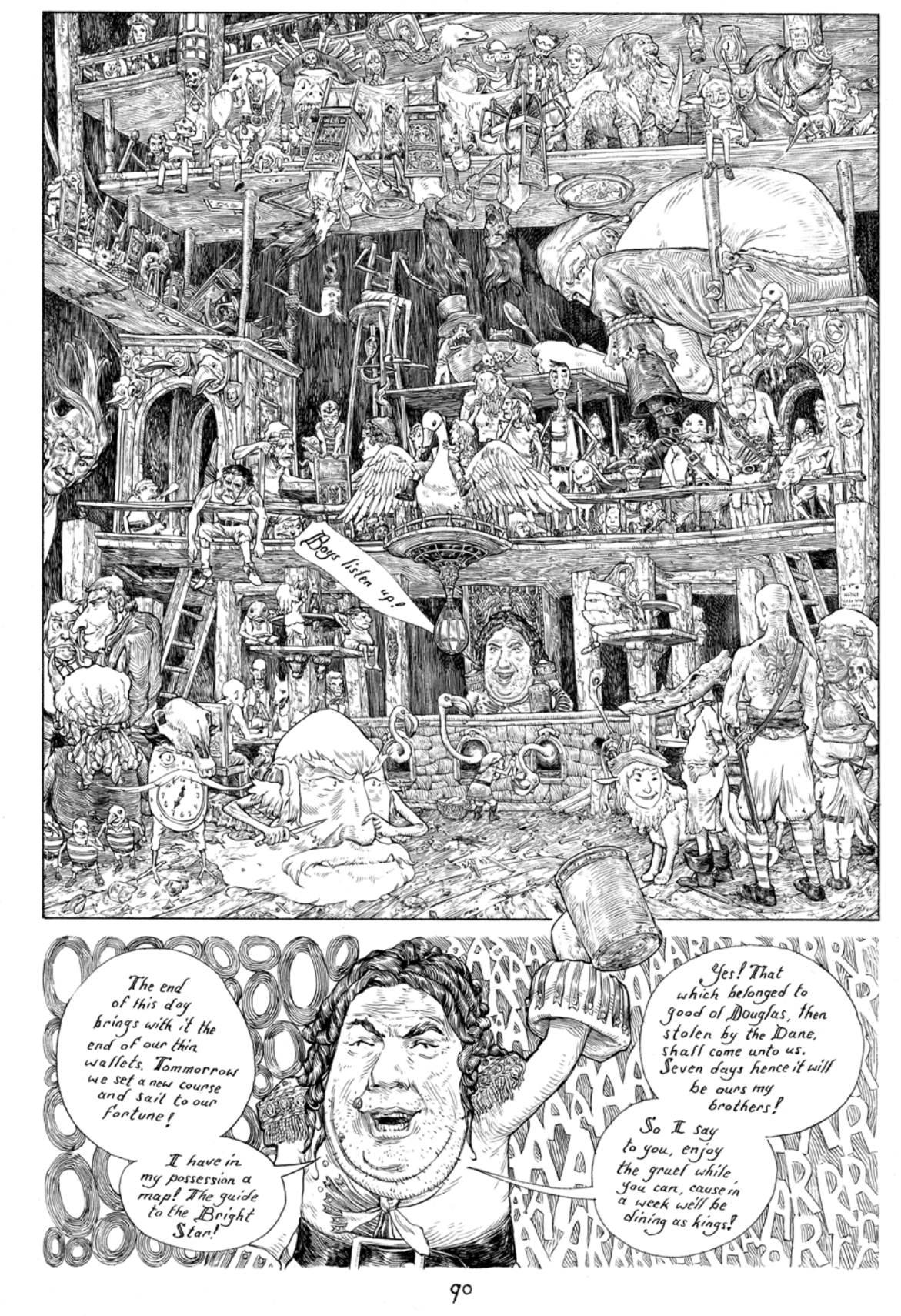

Cursed Pirate Girl, newly (I think) in paperback, is more committed to its aesthetic than any other comic you shall read, this or any year. Jeremy Bastian's art style, a chimera of 18th and 19th century political cartoons, Winsor McCay's Little Nemo in Slumberland, and the intricate doodles that fill the back covers of school notebooks nationwide, turns every page of this book into a veritable feast for the eyes. Every panel looks like it took a week to get just right, which might explain why the series produces roughly one issue per year. It would not surprise me to learn Bastian did not draw, but etch, each page on a plate made from reclaimed pieces of actual pirate ships, then printed it onto paper he made himself from scratch. This is dedicated, artisan work.

The examples shown above barely represent the level of detail present on each page. Thank God the book is in black and white, probably because it would drive any colorist to either the madhouse or an early grave. Indeed, the sheer density of each page, and the nigh-calligraphic letting, can cause the reader to tire. I had to take the book small chunks at a time so as to not strain my already weak eyeballs. Doing so allowed me to savor the splendor of each sequence.

The amount of detail crammed into each panel, though, does not lend the art a clinical atmosphere one bit, nor does it hamper the storytelling. Look at those immaculate panel borders, artistic achievements of their very own. Marvel at each individual character or figure, who may only appear in the background for a brief moment or two, but who are each suffused with a unique and whimsical nature to each their own.

The story, concerns the eponymous Cursed Pirate Girl, who has set out on the Omerta Seas to locate her missing pirate captain father. This leads her, one after another, to the various other pirate ships and captains sailing the deadly waters. Her charm and nonchalant bravery also adheres several supporting characters to her side, like Pepper Dice, the talking parrot whose every feather Bastian renders with exquisite precision, panel after panel. Sometimes he hides in a fish, ostensibly to travel the oceanscapes, but also probably to spare hand cramps for the artist. My favorite characters, though, are the ridiculous Swordfish Brothers, vaguely human-shaped undersea knights with giant fish breaks protruding from their chestplates, who can barely stop fighting amongst themselves to lend our heroine aid.

I am reminded most heavily of the numerous Oz books I read as a youngster, where each chapter brought a new fantastical setting and cast of characters. The spirit of Winsor McCary haunts the plot as well as the art, each development producing a new flight of fancy.

So yeah, you should buy it if you haven't already. Future volumes are forthcoming, and worth the wait.

Next: If I can figure out what the hell I just read, I might write about Grant Morrison and Chris Burnham's Nameless.

Further cries for help can be found @billreads on the Twitter.