Over the past decade, Nick Bertozzi has spent his career working on one critically acclaimed project after another, from "Jerusalem" (written by Boaz Yakin) to "Houdini: The Handcuff King" (written by Jason Lutes) to "Stuffed!" (written by Glenn Eichler). In addition to working as part of a creative team, Bertozzi has also written and illustrated a number of books on his own, including "The Salon," webcomic "Persimmon Cup" and a series of graphic novels about famous explorers.

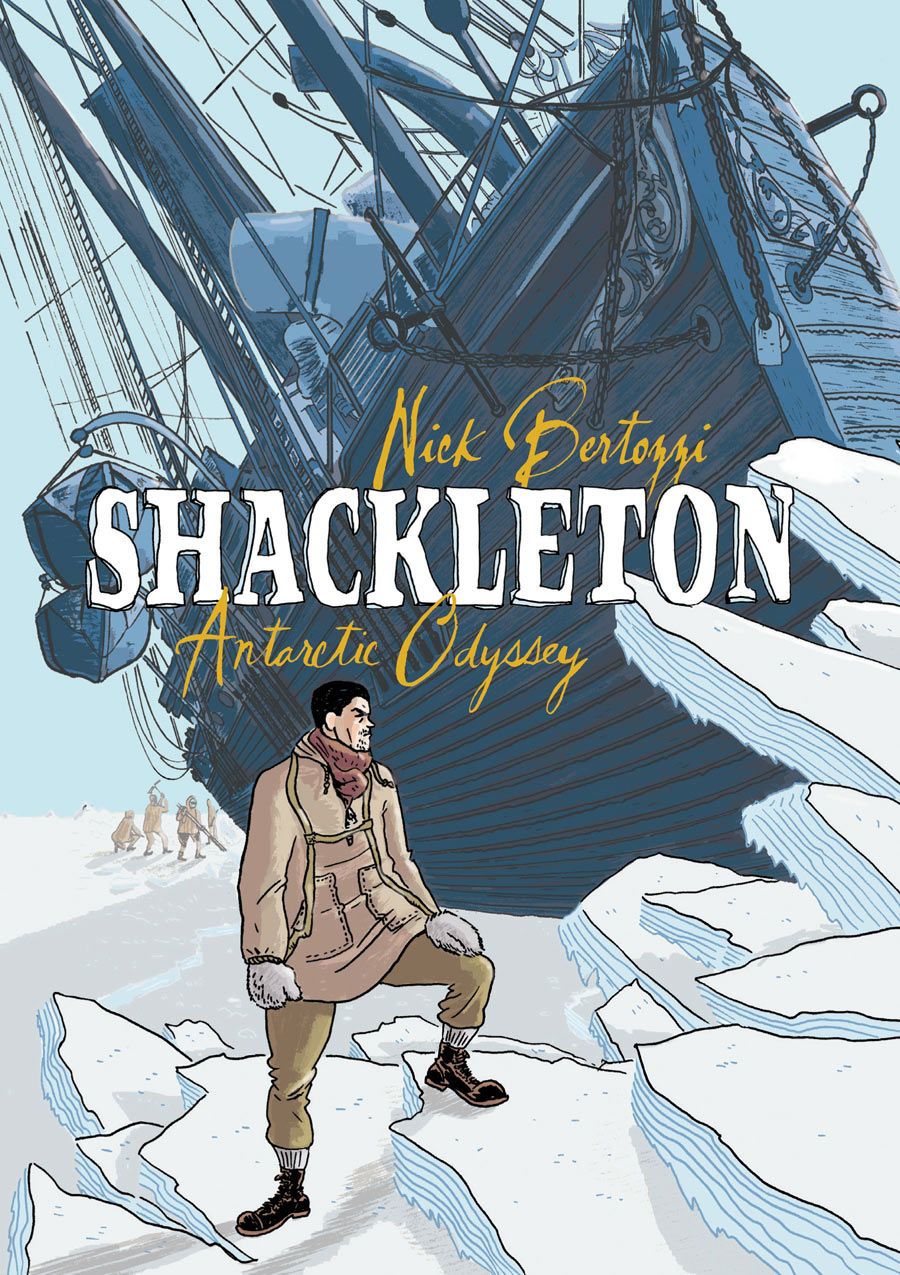

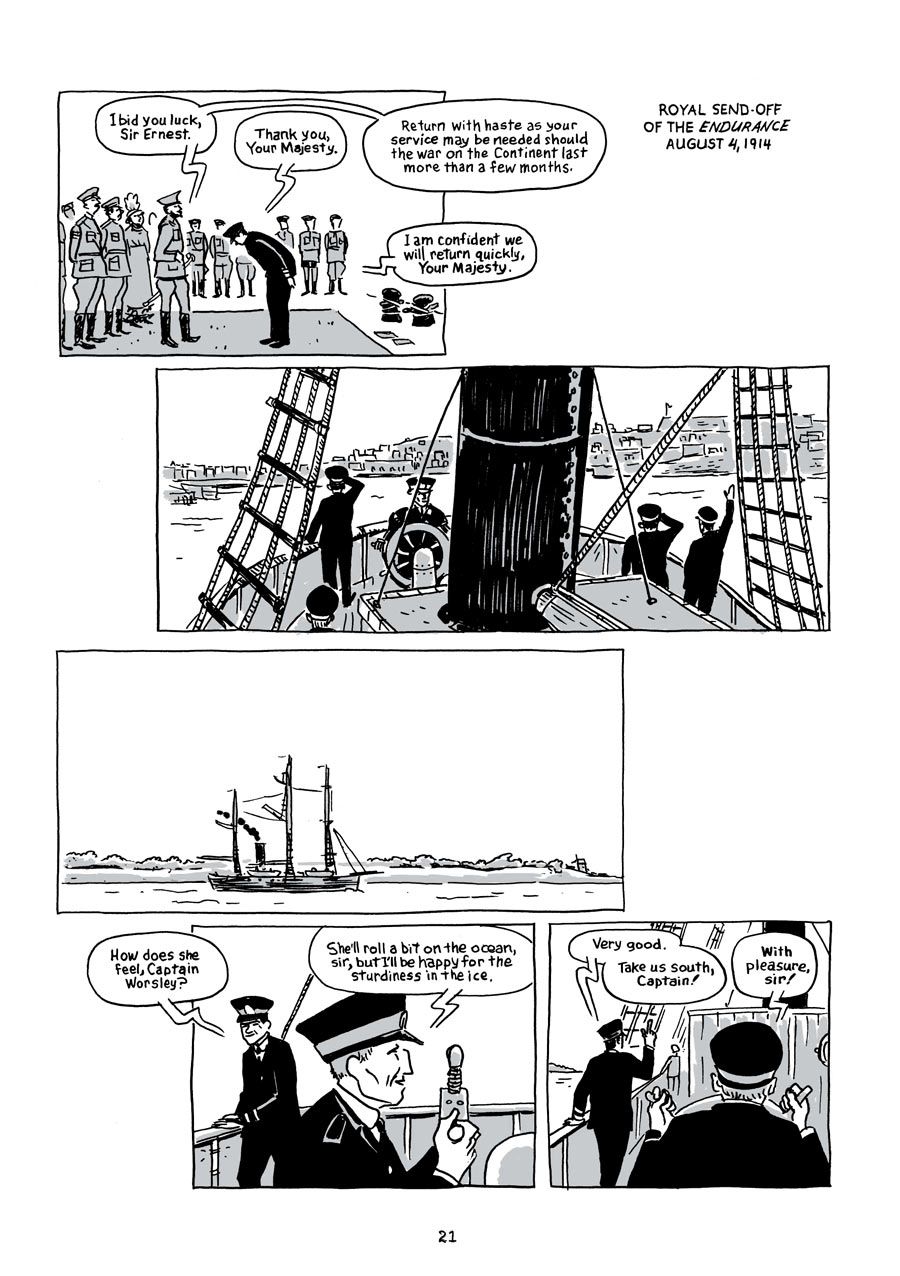

In 2011, Bertozzi released "Lewis & Clark," an incredible book about the journey across the American continent to the Pacific Ocean. Three years later, the cartoonist continues this series with a new book, "Shackleton," available now via First Second Books. It tells the story of the famous Antarctic expedition by Sir Ernest Shackleton, who planned one of the most ambitious expeditions of his time -- and the almost unreal adventure that followed.

CBR News: Realistically, you're likely only going to end up making one book about Antarctic exploration. Why "Shackleton?"

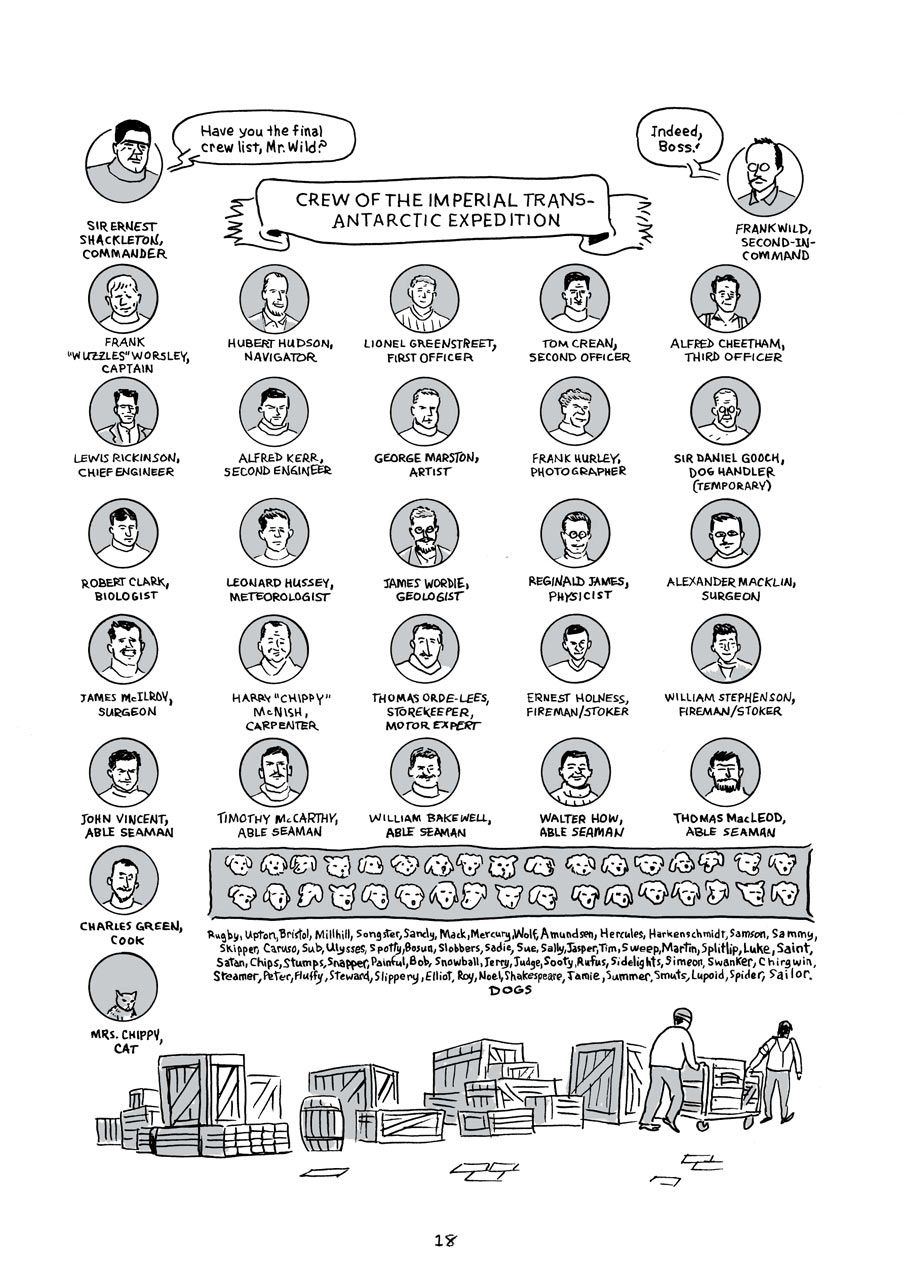

Nick Bertozzi: Shackleton's story is the best story. Not only is it the best story of Antarctic exploration, but the best story ever. The events follow the narrative arc perfectly; the consequences are always death; and everyone lives at the end. I love to tell this story to people who've never heard it -- they don't believe it's true.

This is a tale that's maybe not incredibly well known, though it is an often told story. Documentaries, books including the one Shackleton himself wrote, films, plays -- how did you approach it and find a way to tell it that's yours?

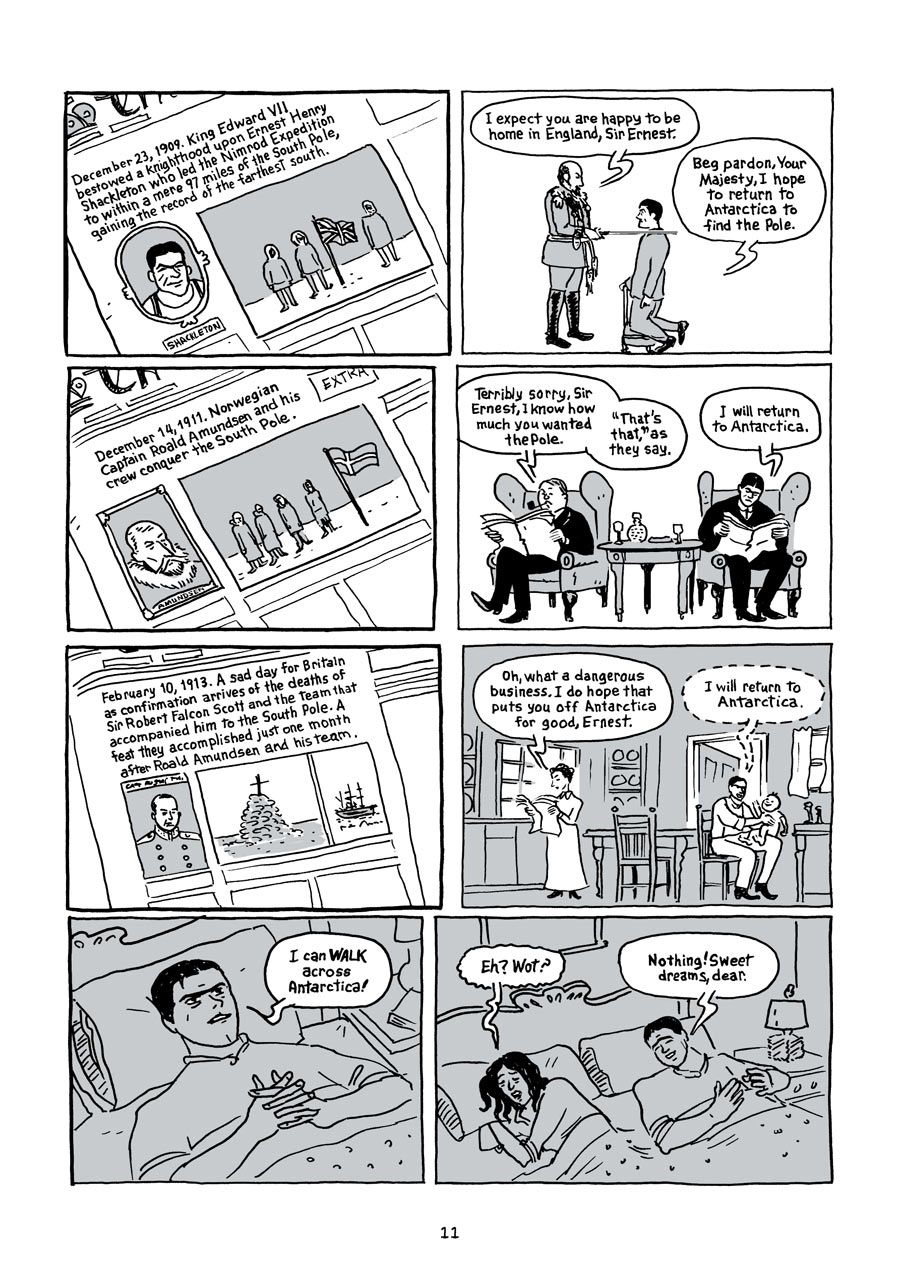

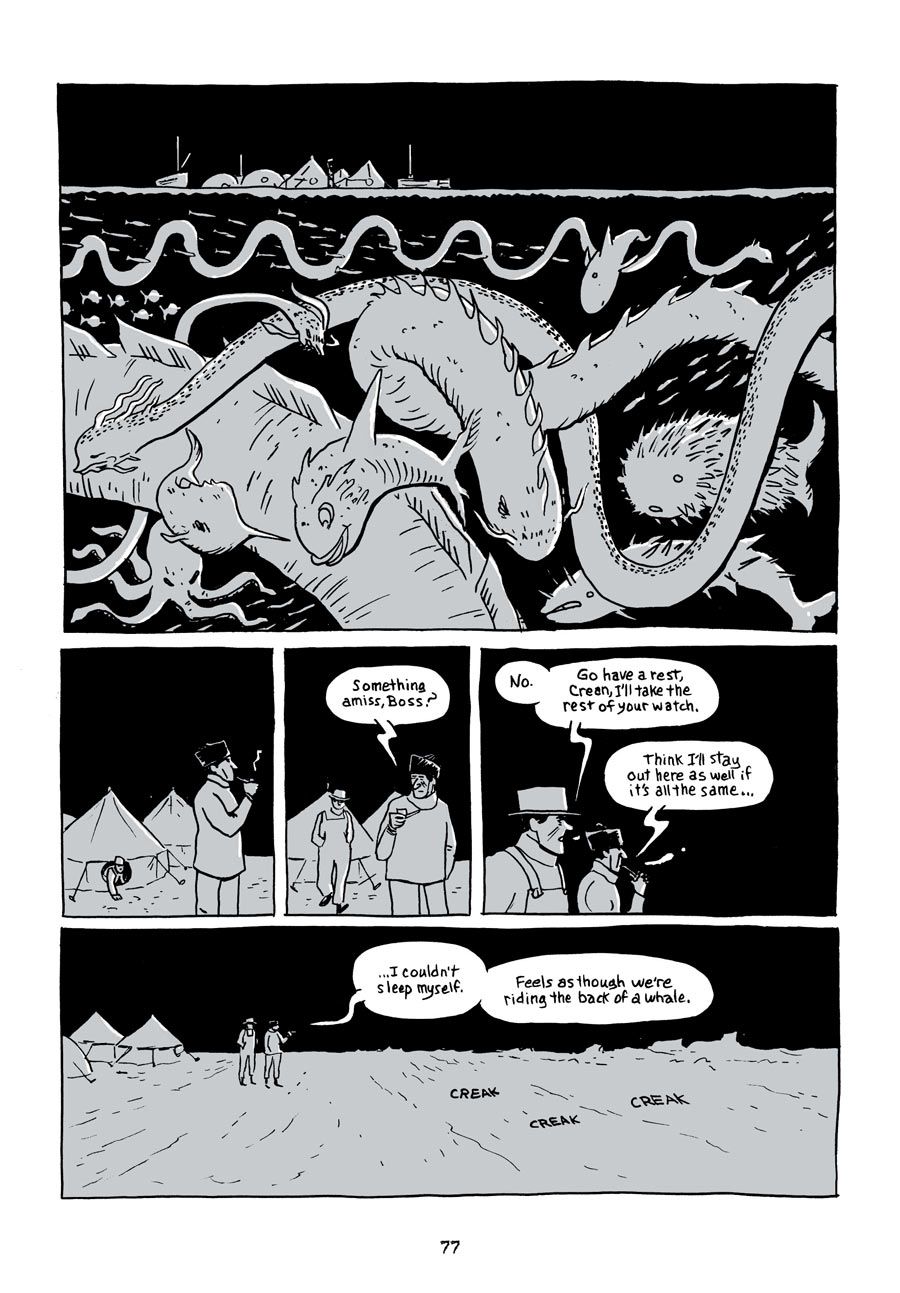

I always try to dispense with barriers between the characters and the readers. I limit the narration as much as possible -- and am frequently advised to add at least a little. I try to compose the illustrations in a way that doesn't give the characters a heroic or better-than-you feel (besides the cover), and I try to elaborate the moments of a history between the names, places and dates. There are so many stories that tell you that the character is in pain; I wanted to show the blisters on their hands and asses.

When we spoke a few years ago about "Lewis & Clark," you mentioned that one of the appeals of their journey for you is that you're a walker. Shackleton's was a walking journey, as well; was this a way into it for you?

It wasn't walking this time that led me into the book. It was sailing. I'd learned how to sail as a young kid at a YMCA camp and spent a good part of my summer vacations on the schooner that my grandfather owned. He'd charter tourists around the Isles of Shoals on the New Hampshire/Maine border. Sailing and sleeping on the water for days at a time is a unique experience, so when I heard about Shackleton's open-boat journey, I had a glimmering of how challenging that must have been.

I will admit, I was a touch heartbroken that "Shackleton" is not in the oversize format that "Lewis & Clark" appeared in. Did you know that from the beginning? Did that change how you drew it and approached the book?

I prefer the larger format, but I was willing to change to see if more libraries and stores would carry the more-popular 6" x 9" size. So far, the answer is, yes, they will. The major differences in approach are gray tone instead of hatching (my chicken scratch would become mud at the small size) and more room on the page given to lettering, which meant that I cut a good chunk of dialogue. Though, that's for the best.

How much research was involved? I'm working under the assumption that you didn't travel to Antarctica.

I read the books, watched the film and looked at the photos, but I didn't get to Antarctica. I have stood on ice. It was pond ice, but that's gotta count for something.

In the book, you balance these vast, epic vistas, this wide open space and how small they are in this landscape, but then there's also this claustrophobic sense.

I'm glad that came across. They were the only people around for hundreds of miles, but when they slept, they had to lie down in tight clumps or they were cramped into tiny boats. And when they were in the boats, there was the constant danger they'd be crushed by closing ice floe lanes.

Did your thinking about Shackleton change over the course of making the book?

Yes. One can read Shackleton literature and easily gloss over that he was a bit of a glory-hound. He could've called off the expedition when he first encountered the unusually-tight Weddell Sea ice-pack. But I suppose that's the same instinct that saved his men in the end -- "We're here, let's make the best of it."

What did you have to leave out that you really wish you could have drawn?

The opening sequence in the book is a series of four-panel gag strips that give the introduction to the story. I repeated this for Shackleton's rescue of the men on Elephant Island at the end of the book, but the tone was too jokey for the drama that had just occurred. I should put those pages online. If I can find them.

What's next for you? Do you have plans for another explorers volume?

Definitely more explorers, though not a man this time. I hope. Maybe I'll try my hand at another artist bio, too. I'm also working on another issue of my "Rubber Necker" series and finishing pages for my webcomic, "Persimmon Cup."

You recently self-published a collection of "Persimmon Cup." How has the response to it been?

It's been thrilling to know that there's an audience for my own idiosyncratic work. It's not an enormous readership, but they made a hardcover book possible. I can't wait for them to see the next chapters. Also, it's a lot easier to draw things out of my head than it is to draw from reference.

For all the people who read this and become Shackleton fans and obsessives, what should they read next?

They've just read the best story ever. They can stare at Frank Hurley's photos.

Nick Bertozzi's "Shackleton: Antarctic Odyssey" is available now.