Cartoonist Ben Katchor is known for his series of acclaimed and beloved graphic novels, including "The Jew of New York," "The Cardboard Valise" and "Hand-Drying in America." The recipient of a MacArthur Genius Grant and a Guggenheim Fellowship, Katchor has also written musical theater and opera, and was a contributor to the legendary "Raw" magazine. He's taught at Parsons School of Design for many years and runs the weekly New York Comics and Picture-story Symposium.

Still, he remains perhaps best known and loved for his comic strip "Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer," which began in the pages of the "New York Press" nearly thirty years ago. The first collection of the strip, "Cheap Novelties," was recently reissued by Drawn and Quarterly in a hardcover 25th Anniversary edition, an event which led to the cartoonist speaking with CBR, pushing back against the idea that the strip is nostalgic, and fighting against the monoculture.

CBR: This is the 25th anniversary edition of your first book, "Cheap Novelties," but I wondered if you could talk a little about how you first started contributing to "The New York Press," where the Julius Knipl comics first appeared.

Ben Katchor: Russ Smith was publisher of the Baltimore City Paper. He sold that, and moved to New York with the intention of starting a weekly in New York. Rather than run the weekly strips that were available -- like Matt Groening, and Lynda Barry -- he decided that he would commission original strips. He got in touch with me and some other cartoonists. It was not something I ever aspired to do. I wasn't reading newspaper strips. The Voice had a few interesting strips but it was not where interesting work was happening.

I tried it and I originally thought it might be a continuing story. I think the night before the first strip was due I realized that no one would follow a continuing story. It had to be self-contained stories. It was pretty all-consuming thing to try to do. It was all I thought about. How to come up with new ideas every week. Although at the beginning it was relatively easy. All of these things that I had seen in New York seemed like a perfect subject matter and it seemed inexhaustible at the time.

You grew up in New York, so you grew up surrounded by this subject matter.

I grew up in Brooklyn, mainly in Crown Heights, and it was kind of this idyllic urban childhood. We still played stickball in the street and I lived just up the block from the Botanical Gardens and a few blocks form the Brooklyn Museum. Even as a small child I had some freedom to walk around the neighborhood. Every corner seemed to have a candy store that sold comics.

As a kid, were you more interested in comic books versus comic strips?

I saw comic strips in the Journal-American and the Daily News and The Mirror. I think a book was a more immersive experience. I remember someone put out these comic book collections of Dick Tracy strips -- Harvey or Dell, I can't quite remember. I remember the chance to read a daily strip in that quantity was a big experience. I can't tell if I was following the continuity of strips at that point; I was looking at them, though. When I was in second grade, I think, Golden Books put out a batch of Tintin albums. They did American translations as opposed to those British ones. I'd never seen anything like that. It was a combination of comic books, newspaper strips and these strange objects like an Edward Gorey book I remember stumbling on as a small child.

I read that your parents spoke Yiddish.

They both could. My mother was born in this country, so it wasn't her primary language, but for my father it was. He came from Warsaw before the war, and he was deeply into this Yiddish speaking culture in New York.

Did you grow up speaking it?

No. He didn't push me to. I think he was more of an internationalist and knew I would be functioning mainly in English. I mean, occasionally we'd speak it, and I'd overhear a lot of conversations in Yiddish, but no, he was acquiring his English and trying to be an English speaker. There were people who sent their children to Yiddish language schools, but I learned to read it much later, by myself. I inherited a lot of his books and I figured I should figure out how to decipher them. As a child, I wasn't expected to learn Yiddish -- or, for that matter, any other language.

I bring it up because New York had this very vibrant Yiddish culture that faded away.

It's still around. The Hasidim still use it in New York. There's a big New York Yiddish conference coming up in the fall. I don't know what the numbers are, how many people are still thinking about it or writing in it or speaking it. A lot of the energy, I think, is historically directed, looking back at the culture.

A lot of people talk about your work and the Knipl strip in particular as nostalgic, which I don't think is quite right.

The Knipl strip was very much talking about the city as I discovered it as a child. It was cataloging everything I saw around me and trying to figure out what it all meant. I mean I don't want the past to come back. I'm not homesick for the past. There were pretty bad things going on in every period of history. It was just about the city. Most mainstream culture was about the moment and not looking back at the history of a city. Maybe those kind of details seem antiquated to people, but it's an old city. The past coexists with the future and the present in New York. It's always there.

I mean, I'm sitting in a room from 1905. Some of the walls have been repaired a bit but the original molding is there, the original floor is there. I don't see talking about the old things in New York that still exist as nostalgia. Maybe now 25 years later it may appear more nostalgic. It's not even about New York City. It's about an imaginary city like New York. I don't know if you can be nostalgic about an imaginary city. Usually you're nostalgic for something you knew and that's gone or you read about it and it no longer exists but this is a piece of fiction.

I think that the strip inspires nostalgia in people because it's about the city changing and places being lost and forgotten and today even more than 25-30 years ago, New York and every city is becoming increasingly homogenized. I mean how many Duane Reade stores are in New York?

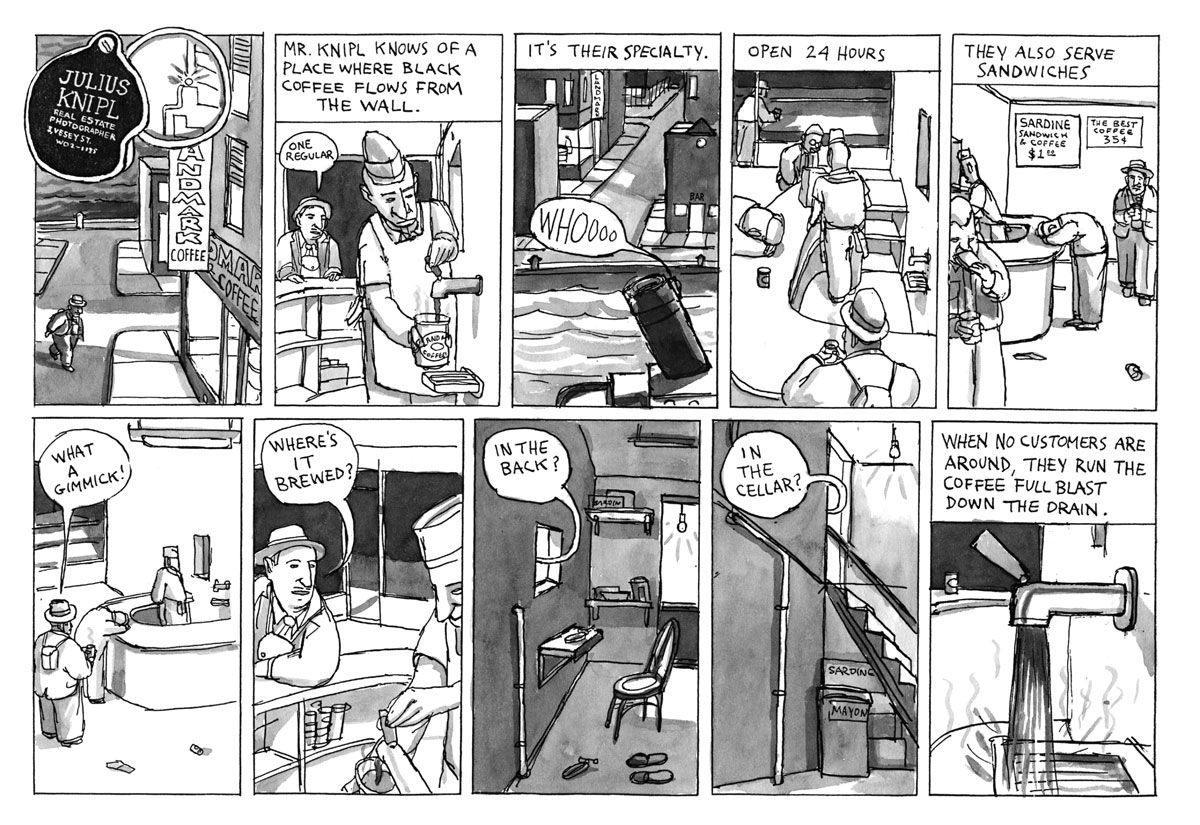

I remember when there was one -- between Duane and Reade Streets on Broadway. [Laughs] That was the original one. A lot of the strips were also about mechanisms within the city, how city life works -- there's a lot to say about how things work. The streetscape has become much more boring, I think you could argue that. I mean since those Knipl strips started the city has moved further towards being a complete mall. There's a lot of chain development and a really deadening urban design. Do I look back and say there was a more livable city, a more interesting street life? I miss that.

People visiting can say, these are the same stores I see in my local shopping mall. Why did I come to New York? It's this kind of incredible poverty of imagination of big companies and the people who okay things in those companies. The ruining of the environment, the ruining of the streetscape of cities -- these were decisions made by people with pretty limited goals, to take the money and run and not think about what their actions mean. No big picture. It's boring. The streetscape is is almost the least of our problems now, but it's all interconnected.

At one point reading "Cheap Novelties" I was reminded of Bill Griffith's "Zippy." He loves to incorporate real signs and roadside attractions and unique places -- you may not use real places, but you both have this interest in the unique, in the personal, in the handmade.

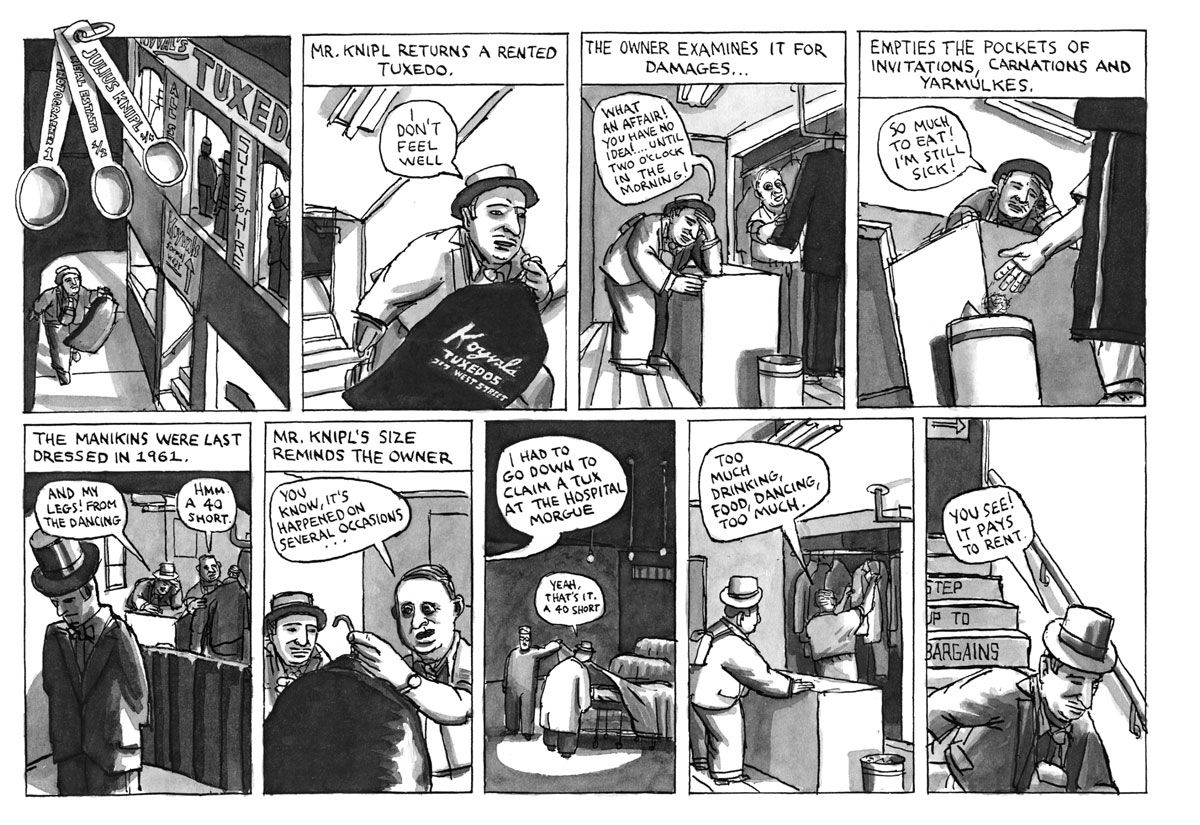

I purposely didn't want to write about the real world and real things that exist in New York. I also kind of tried to avoid anything that might be considered picturesque about a city. I think a lot of these Knipl strips are about these tremendous limitations placed on people. Like the strip, I think it's in "Cheap Novelties," about this repetition of certain kinds of people who open up pizza places. There's this model they have. Even on a small business level people feel hemmed in and invention becomes pretty complicated. Or just difficult to say I'm going to sell a soft drink but nobody knows about it nobody wants it, how am I going to sell that?

That's what's so interesting when people say that the strip is nostalgic. You're not saying things used to be great. They used to be different and more unique, maybe, but they weren't easier.

No, definitely not easier. Most small business people were struggling. It's much easier to get a job sitting in an office of a big corporate headquarters and look at the internet all day. There's no need for any invention. It's all boiled down to: here's what Starbucks looks like and don't think about reinventing it in any meaningful way. Here's a new sandwich or piece of cake this year. It's all driven by some accountant figuring out how to squeeze the most money out of this big operation. It's kind of sad. I think that kind of thing probably always went on among businessmen, but not on such a big scale. The desperation was on a smaller scale. And its effect wasn't as devastating.

It may as well be a state run coffee shop! But I don't think even a government agency would do it in such a boring way. There should be regional variations. The idea that it should be the same across the country with pretty minor variations.

Post offices look different in each town.

Sure, when the federal government did it they tried to reflect regional differences and regional tastes. I don't know. Accountants are only inventive about how not to pay taxes. [Laughs] They're not inventive on other levels.

I miss the idea that there was competition among businesses. In New York there would be four bakeries in the neighborhood. Each one would come up with their own specialties so you could only get this here and you couldn't get it at the other three. But this is how these where the economic system we live under leads to. There are only these two political parties that get any visibility from the mass media. It's the same in politics and coffee shops and cheap clothing. [Laughs] That's why I said it's all interconnected. I think that the world has to be revitalized on all those levels -- not just on the level of streetscapes and consumer options, but on every level.

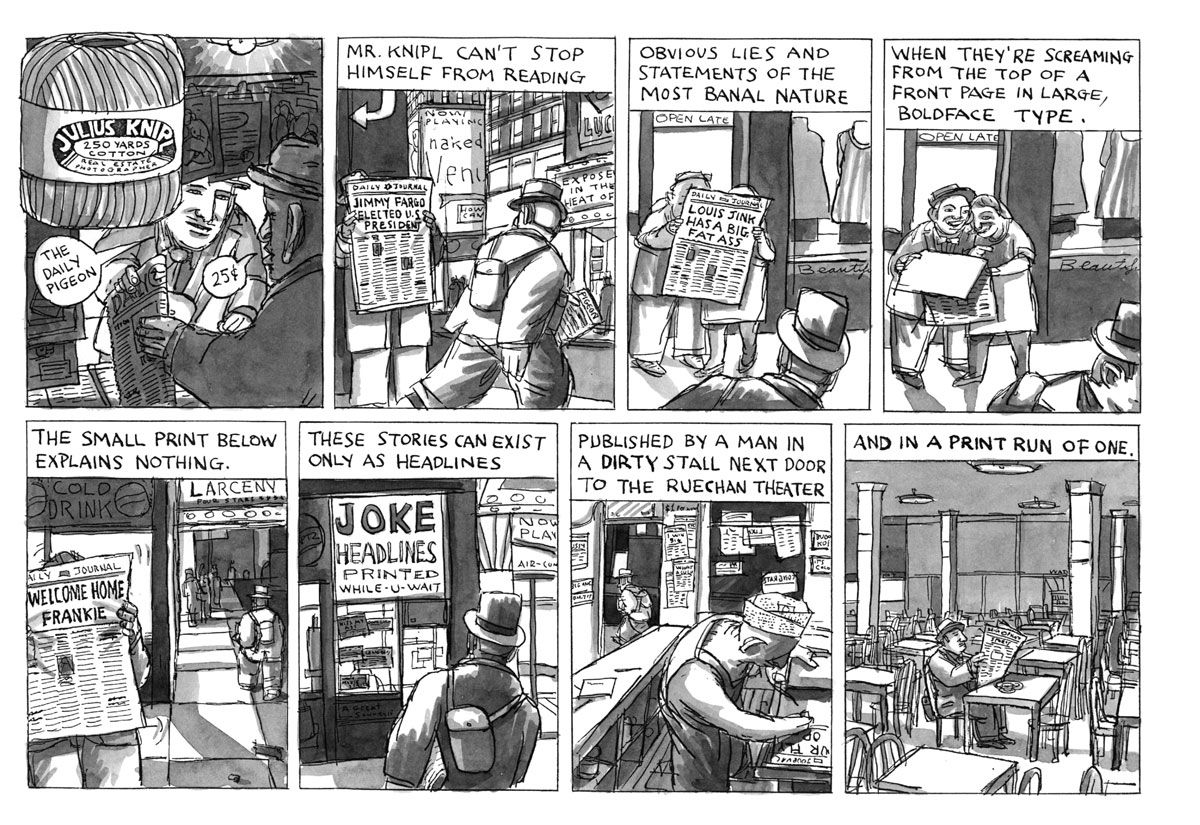

Included in this new edition of "Cheap Novelties" is "The Daily Pigeon" which is a four page sample newspaper. Where did this come from?

In that imaginary city that Knipl operated in I invented several newspapers. The Daily Pigeon was one of them. For an exhibition that I had I said I'll make a four page sample of this newspaper. Those illustrated newspapers that were the counter to the New York Times or the heavy text based newspapers had all the strange features and the layout was completely insane diagram of every human appetite and every mad ad mixed in with strange syndicated columns. I remember seeing those as a kid and some of them had pretty odd comic strips. These were less wholesome looking strips. [Laughs] I just wanted to make a newspaper, an actual artifact form the world of Knipl's city.

So you made an artifact of a fictional city from a comic strip that inspires nostalgia in readers for a city that may or may not have ever existed?

[Laughs] I don't know. I've always lived in cities. Everywhere Knipl ran -- Providence or Chicago or wherever -- people said, I know what this city is. It's based on my city. I just wanted to invent my own city. Forget about inventing a coffeeshop, I wanted to invent everything and in a comic strip you can do that.

You could fight against this kind of homogenization, if you dare to. To make a comic strip like Knipl was going completely against the grain of what a comic strip should feel like. It shouldn't need half tone printing and deal with what people thought was very obscure subject matter. That's not what the industry wanted. I didn't really care about that. I wanted to make a kind of strip that needed to be made. Somebody at King Features once looked at it and said to me, we can't sell a strip like this. It doesn't deliver what we think a comic strip should be. If I had listened to them, we wouldn't be talking about this. [Laughs] It would be another boring, failed comic strip.

So we have to go against the grain. Especially in art. In politics they say the lesser of two evils. No. In art you pick the best thing you can do. And if it's around long enough it will have an impact on the culture. You don't say, these are the two best selling comic strips which one should I imitate? That's not a good approach. I think you should constantly try to correct the culture through your work. There should be a critique of comics as they exist. It got published because it was in this alternative weekly world where there was some latitude. The editors weren't that stupid to say this is not what people want. They said, we don't know what people want, what do you think they want? Then something interesting comes about. My whole approach wanting to make comics was to correct the comics I grew up with. I just thought they weren't good enough. I think people doing alternative comics, people questioning comics like Crumb questioning what you could do in a comic strip in the sixties, changed the world. It did have an effect. I don't think it did at the moment he did it, but the impact of that decision opened up the culture.