After 75-plus years, Batman has accumulated more than his share of landmark creative teams. Bob Kane, Bill Finger, Jerry Robinson, and (occasionally) Gardner Fox laid the foundation for the likes of David V. Reed and Dick Sprang, John Broome and Carmine Infantino, Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams, Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers, and Frank Miller and David Mazzucchelli. By the 1980s, the Bat-books were becoming a virtual cottage industry, weaving storylines between "Batman" and "Detective Comics" and tag-teaming artists like Don Newton, Gene Colan, and Tom Mandrake with writers Gerry Conway and Doug Moench.

In the '90s the line exploded with spinoffs for various Bat-associates, which in turn produced mega-arcs designed to employ them all. Add the anthologies ("Legends of the Dark Knight" and "Batman Confidential"), the occasional "Outsiders" revival, and miniseries galore and the level of Bat-product went through the roof. Although there were a number of standout creative teams, such a crowded field made it hard for any particular one to dominate, not just in the '90s but well into the 2000s.

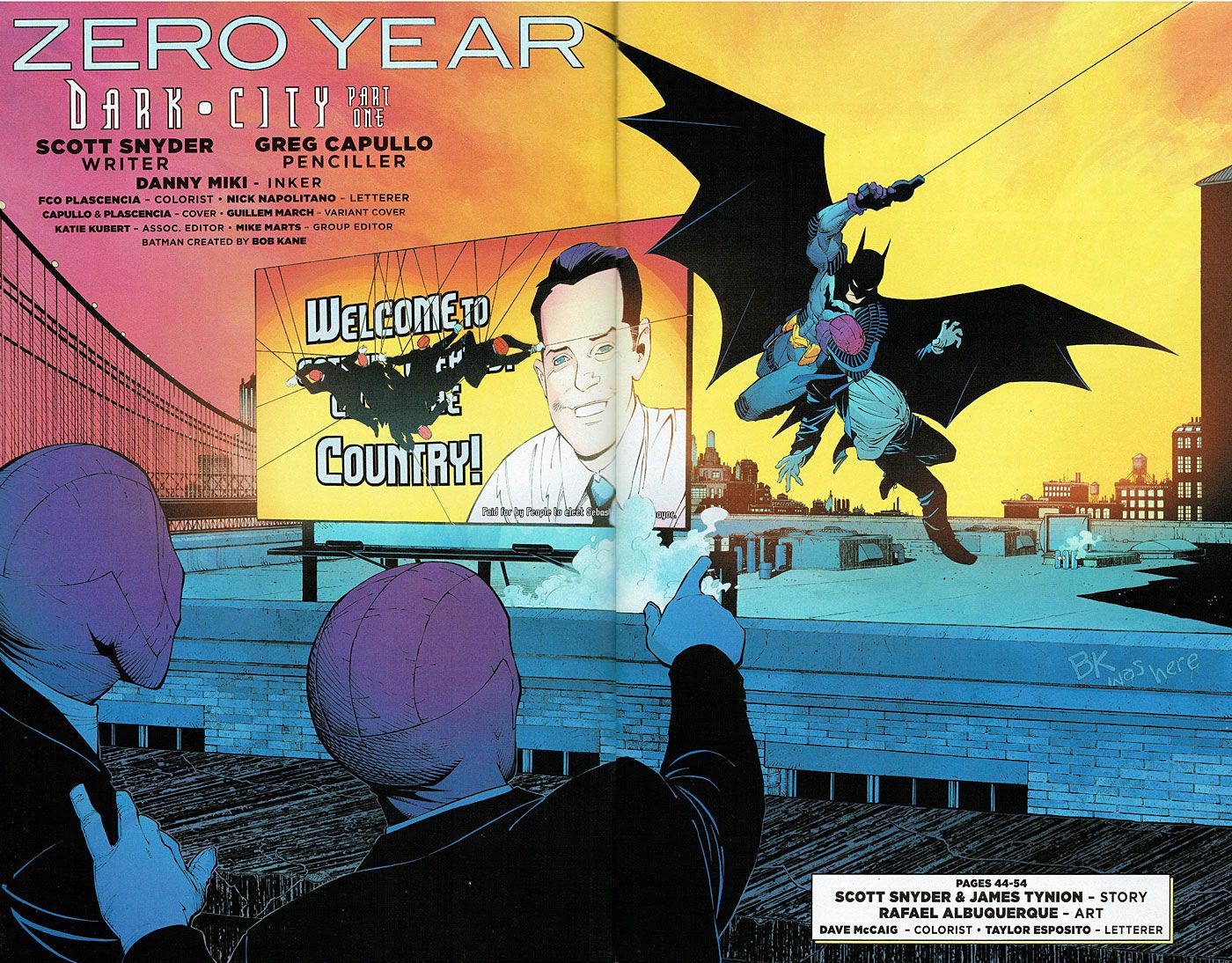

That was the status quo in 2010 when writer Scott Snyder started penning the adventures of Dick Grayson's Batman in "Detective Comics." Writer Grant Morrison (alongside various artists) had been shepherding one Bat-book or another since 2006, eventually making Bruce Wayne into a globetrotter for "Batman Incorporated." Accordingly, while Bruce was away, Snyder remained in Gotham along with artists Jock and Francesco Francavilla and filled their "Detective" run with eerie, compelling tales of a next-generation Dark Knight. In 2011, the New 52 relaunch moved Morrison to "Action Comics" and Snyder to the main Bat-book, which he and penciller Greg Capullo have made their own for most of the past five years.

5-STAR REVIEW: Snyder & Capullo Bid "Batman" the Perfect Farewell in Issue #51

April's "Batman" vol. 2 #51 marked not only the final issue from Snyder and Capullo, but the final issue for the only writer/penciller team to remain unchanged since DC's New 52 relaunch in 2011. Other notable teams from the Class of '11 left their series largely on their own terms, whether they told a single extended story (like Morrison and Rags Morales on "Action," or "Wonder Woman's" Brian Azzarello and Cliff Chiang) or a series of arcs (like Geoff Johns and Doug Mahnke's "Green Lantern" or Francis Manapul and Brian Buccellato's "Flash"). Snyder and Capullo took a middle ground, crafting discrete story arcs which can stand alone, but which combined into something uniquely their own. Today we'll look back at their work, and see where it might rank in Bat-history.

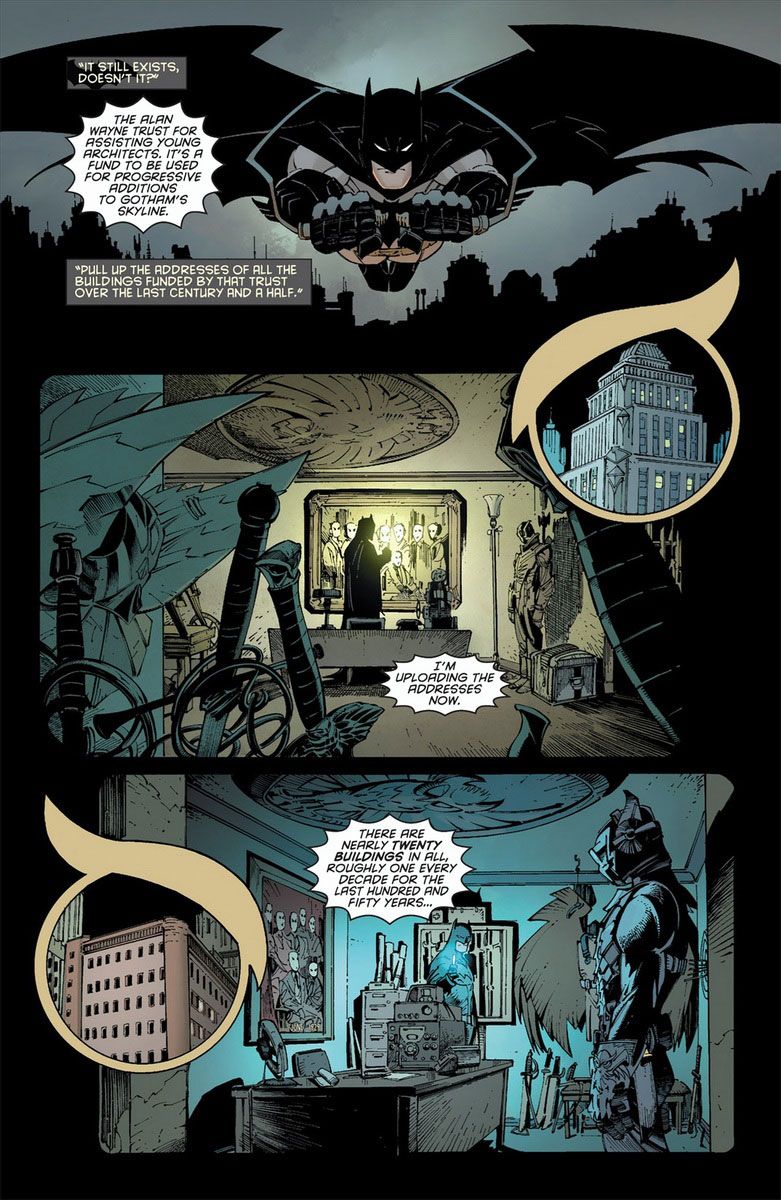

Still, not only do these arcs alternate between long and short, but the retelling of Batman's origin in "Zero Year" is in the middle of all of them -- which is appropriate for a story whose plot threads reach into the other arcs. The Owls are virtually the avatars for Gotham itself trying to kill Batman, the Joker arcs describe a very personal (and twisted) relationship between hero and foe, and "Superheavy" is about Gotham's attempt to create a Bat-replacement; but "Zero Year" is Snyder and Capullo's thesis statement on Batman's relationship to the city.

Snyder had already begun exploring that relationship in his first "Detective" arc ("The Black Mirror," which also featured a masked secret society) and in the miniseries "Gates of Gotham"; so not surprisingly, it played a significant role in "The Court of Owls." Making Gotham City a "character" isn't a new idea, strictly speaking and neither is the idea that Gotham's power structures would be opposed to Batman. What is new, though, is this notion of Gotham itself as a living thing, creating those oppositional power structures, from a corrupt police department and unchecked criminal element to an evil avian-themed ruling class. Over the course of their run, Snyder and Capullo played with this idea right up through their final issue, which emphasizes the good people who work together to make the city better for everyone.

Turning attention back to the Owls, a signature Snyder/Capullo creation which caught on quickly. In introducing the Owls, "Court" does a fairly slow burn on the whole concept, teasing the idea that they're somewhere between a kid's nightmare and a conspiracy theory, and hiding their existence in a procedurally-inflected murder mystery. Not until the trippy issue #5 does the society really become a credible threat. There, a drugged Batman staggers through an Owl maze (and the reader has to physically rotate the comic book to read) only to be stabbed by the Owls' enforcer. Batman fights back in #6 and escapes in #7, but the arc ends on the cliffhanger of a Talon army coming for him.

Snyder & Capullo Finish Epic "Batman" Run With A Love Letter to Gotham

One thing about "Night of the Owls" and the two Joker arcs: they read a lot more quickly in big chunks than they did in single-issue form. This is mostly due to their action-heavy plots, which is understandable -- "Night" especially is basically a series of fights and chases -- but for someone who read these arcs initially in monthly installments, it brought back just how eventful each single issue was. That goes double for the denser material in "Court," "Zero Year" and "Superheavy." In other words, Snyder and Capullo excelled at giving each issue an innate drama, building and releasing narrative tension according both to the demands of the story, and the rhythms of periodical publication.

By contrast, the Bat-crossovers of the '90s and '00s were events almost by default, since they tended to involve the ancillary Bat-books and could unfold in different titles throughout each month. Later, the arcs from Morrison and company stayed largely in whichever book he was writing, so they reflected his unadulterated view of the characters. Likewise, while Snyder and Capullo's arcs allowed for crossovers (which only "Court" ended up lacking), they kept the main action within the "Batman" title.

It's a lot of long-form storytelling, even without those crossovers. Moreover, while "Batman" was serializing "Zero Year" and "Superheavy," Snyder also headed up the writing teams for two weekly miniseries, the year-long "Batman Eternal" and the 6-month "Batman & Robin Eternal." All that outreach speaks volumes about the desire to piggyback on this creative team's success. Sure, in the '70s a lot of writers and artists tried to emulate O'Neil and Adams, and in the late '80s Frank Miller cast a long and distinctive shadow. However, those folks created hard-to-ignore paradigm shifts. Let's put it this way: I don't remember any of the '90s creative teams actively trying to ape another, nor do I think that the other Bat-books necessarily took Grant Morrison's lead in the mid-to-late '00s. Instead, they were all trying to present a unified front while telling their own stories in their own styles.

That's not really a bad thing. Neither am I saying that Snyder and Capullo have imposed their collective will on the Bat-books -- far from it. Rather, they created enough space for other creative teams to express themselves freely. For example, Snyder clearly was the Sinatra of this "Bat Pack" (#sorrynotsorry) in terms of setting an example for other books' writers. This is evident in the "Eternal" miniseries, which have Snyder's name at the top but which are largely the work of other teams. I don't know that you see that kind of influence outside of someone like Denny O'Neil, who eventually became the Batman group editor. (Not that I am suggesting anything, but I could definitely see Snyder as group editor one day, albeit far in the future.)

Scott Snyder Talks "Batman" Finale, "All Star" Future & Love for Capullo

Speaking of editors, no doubt a big key to this intertitle cultivation is current group editor Mark Doyle, who succeeded Mike Marts on the Bat-books early in 2014, and who came over from Vertigo where he'd already been working with Snyder on "American Vampire" and "The Wake."

Since then, Doyle has overseen new directions for the Bat-line in unexpected ways, from the "Batgirl of Burnside" makeover of Barbara Gordon to the launch of new series like "Gotham Academy" to "Harley Quinn" and "Gotham By Midnight." While Snyder didn't hand-pick Doyle, it's hard not to see the move as part of DC's desire to keep Snyder happy. I'm not saying Scott Snyder is responsible for "Harley Quinn" or "Black Canary," but I do wonder whether Doyle would have moved to the Bat-books if Snyder weren't already there. In any event, Snyder and Capullo had been working pretty well with the other Bat-teams under Marts' editorship, so at the very least Doyle's hiring is a happy accident that seems to have paid off handsomely.

Ironically, for all this talk about Snyder and Capullo's work, it's hard to define their style in simple terms. The phrase "grounded but dynamic" comes immediately to mind, since they blend a familiar first-person-narrative-procedural approach with a willingness to test the limits of what makes an acceptable Batman story. Although focused almost exclusively on Gotham City, Snyder and Capullo haven't been content with mere misanthropic urban avenging. Their "Batman" (whether book or character) has embraced all of the character's relationships, from Gordon and Alfred to Superman, the sidekicks, the Justice League, and even the Joker. Morrison famously sought to incorporate all of Batman's history into his run, and Snyder's work betrays a similar appreciation. Still, it's more than just his love for the character and awareness of the vast Bat-lore. It's his desire to approach every new story as his last, so that he tells the story he would want to read as a fan.

While we're on the subject of "last stories," issue #48's conversation between a Bruce and Joker who have each become uncoupled from their adversarial alter egos will no doubt be studied by future Bat-scholars looking to psychoanalyze either or both. Snyder and Capullo took tremendous risks with "Superheavy," starting with the new Batman, escalating to a happy, well-adjusted Bruce and Julie, and ending with an array of alternate Bat-futures and a genuinely fantastic restoration sequence which made Superman's 1993 resurrection look like a "Highlights" science project. The fact that Snyder and Capullo pulled it off is testament both to their abilities and to the goodwill their work has generated.

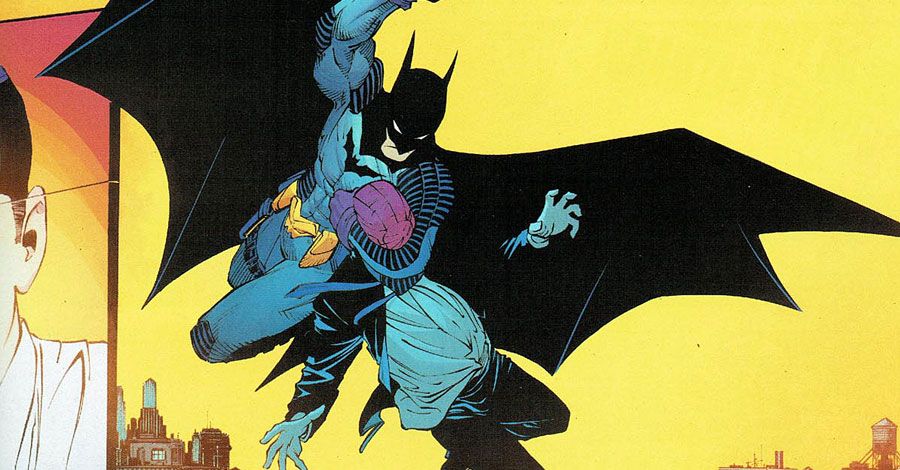

Naturally, much of this invention -- which started with the Owls' gothic menace and included "Zero Year's" retro-post-apocalyptic Gotham before it ever got to the radical departures of "Superheavy" -- wouldn't have worked nearly as well absent Capullo's accessible work. Even outside of the "Bruce Abides" of "Superheavy," Capullo's Master Wayne seems fairly laid-back when out from under the Bat-hood -- just as his Batman is appropriately amped up. Uncomplicated but weighty, Capullo's figures have a visual economy reminiscent of Bruce Timm's animated series designs or Norm Breyfogle's energetic cartooning; and his backgrounds are meticulous without being busy. Imagine another artist doing so well with inventions as diverse as the creepy Owl masks, the steampunkish Talon outfits, the nightmarish Dr. Death and Mr. Bloom, or the over-the-top "Justice Buster" and "Rookie" battlesuits.

It practically goes without saying that Capullo's capacity for setting the right mood has also been key to this series' success. Contrast the stark terrors of the Owls' maze and the lurking horrors of the Joker issues with "Zero Year's" daylight battles or "Superheavy's" emotional moments. "Zero Year" may be this team's magnum opus, but "Superheavy" sure demonstrates their range. Putting a mohawked, buff Jim Gordon in a mecha Bat-suit is on par with Marvel's equally unexpected move of bringing back Bucky Barnes as a cyborg assassin, and it takes a great creative team to pull it off. Aided by inkers Jonathan Glapion and Danny Miki, and colorist FCO Plascencia, Capullo has done a heroic job bringing Gotham and its residents to life, so that Snyder can examine how they all interact.

In that respect it's only fitting that Snyder and Capullo's final issue is an epilogue for their big hits, checking in with the Arkham inmates, the Owls, and the dormant Joker. Meanwhile, as Batman tries to solve the mystery of Gotham's sudden blackout, he encounters a newspaper columnist who was a small-time crook until a Bat-encounter convinced him to go straight. The story is forthright almost to the point of corn -- the ex-crook now writes the "Gotham Is..." column described in the first pages of issue #1 -- but by this point Snyder and Capullo have earned their sentimentality. They tell the readers of "Batman" that "Gotham is" everyone who has contributed to the book's success, whether as a professional or a fan. Drawing on Batman's inspirational qualities, the narration describes it as "what we say to [Batman], and what [he] says to us." The only thing missing is a group hug -- which, again, for a lesser Bat-team might be hard to pull off.