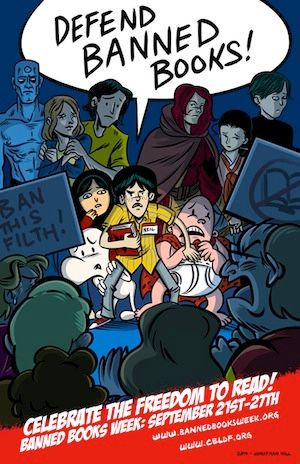

This year's pairing of Banned Books Week and comics, with considerable input from the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, was pure genius. While it is sponsored by a number of organizations, Banned Books Week is heavily supported by libraries, and librarians have been among the most ardent boosters of graphic novels in the last ten years.

In fact, Banned Books Week is really all about libraries, and to a lesser extent, schools. The days of government censorship in the form of prohibiting publication, import, or sale of a book for offensive content are long gone. Nowadays, "banned books" really refers to books that someone wants to remove from a public library or a school. Often, those attempts are unsuccessful because the library in question has a solid acquisition policy and a process for handling challenges, which is how it should be. Libraries buy books for a reason, and they shouldn't take them off the shelves without a better reason.

Many public library challenges have a similar narrative: Kid checks a book out of the library, mom finds the book and freaks out, mom goes to the library, or the press, and demands the book and all others like it be removed from circulation. When the proper process is followed, a committee of professionals reviews the book and makes a decision, and you and I seldom hear about it; it's when someone goes to a public meeting and starts yelling and waving a book that things go haywire. That's what happened in South Carolina, where the a mother let her daughter check out Alan Moore's Neonomicon, which the library had correctly shelved as an adult book, then was shocked to discover it had sex in it. In this case, the library review committee recommended that the book remain on the shelves but the library director overruled them.

Another political-football case that ended badly was the removal of Paul Gravett's Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics from the San Bernardino County Library System. In this case, an elected official with ambitions for higher office, Bill Postmus, led the crusade, strong-arming the county librarian into removing the book because of a few images. It should be noted that the book was purchased at the request of a patron and had gotten favorable reviews in a number of professional journals. This illustrates another common feature of book challenges, the tendency of the challengers to focus on a few images as opposed to taking the book as a whole. (As a footnote to this story, Postmus's career didn't go much further than that as he ran into trouble with the law on drug and corruption charges and ultimately admitted to taking a $100,000 bribe. But hey, he protected the good people of San Bernardino from drawings of hamster sex!)

This is why organizations like the CBLDF are important. They are a counterweight to the forces of ignorance, prejudice, and political expediency that lead to things like a reference book being removed from a library because of a few images or a state legislature punishing a public college for including a book about gay people in its recommended reading for freshmen.

That said, if there's one thing Americans hate, it's being told what to do. That goes double for teenagers, who are often the ones these challenges purport to protect. Book sales and library circulation often go up when there is a challenge, and sometimes the larger community is spurred to action. After the Gravett book was removed from the San Bernardino libraries, the nearby Barstow Community College bought several copies and put them on prominent display; the librarian there also had some choice words for the library that pulled it.

In 2009, two library assistants in Jessamine County, Kentucky, were fired for keeping Alan Moore's League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier checked out for over a year (a sort of backdoor challenge) and then looking up the personal information of a patron who requested it. The following year, Jessamine County librarian David Powell, who successfully defended the book, told a panel at C2E2 that while there was a lot of local controversy, support poured in from all over the country. "We had a lot of people from all across the country send us copies of the book, and our circulation skyrocketed," he said. "We now have three copies on the shelf, and I have a stash of them, so if they disappear I can put another one out."

Jeff Smith was all over the place during this year's Banned Books Week—on NPR, with Dav "Captain Underpants" Pilkey; in The Guardian, with Barbara Jones, director of the American Library's Office for Intellectual Freedom; and in the Washington Post, with Scott McCloud and Neil Gaiman. Smith's Bone is one of the top ten challenged books—not graphic novels, books—in the country, for reasons that no one except the challengers seems to understand. The fact that he has emerged as a leading spokesman for freedom of speech is just more evidence that efforts to suppress a book often have the opposite effect.

[Editor’s note: Each Sunday, Robot 6 contributors discuss the best in comics from the last seven days — from news and announcements to a great comic that came out to something cool creators or fans have done.]