John Allison is one of the pioneers of webcomics. Since launching "Bobbins" in 1998, Allison has continually evolved his comics, as his strip and approach morphed through two more incarnations: "Scary Go Round" in 2002 and "Bad Machinery" in 2009, which recently came to a close after a five year run. For a decade-and-a-half, Allison published comics five days a week -- sometimes more -- singlehandedly creating a body of content the depth of which rivals most fledgling comics publishers catalogues.

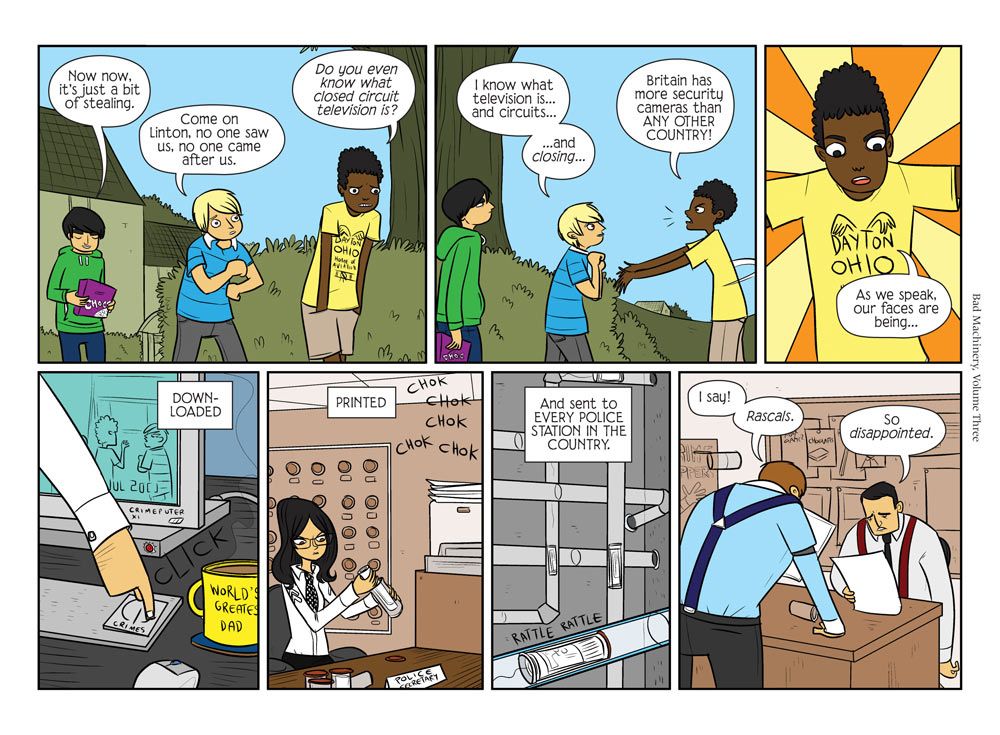

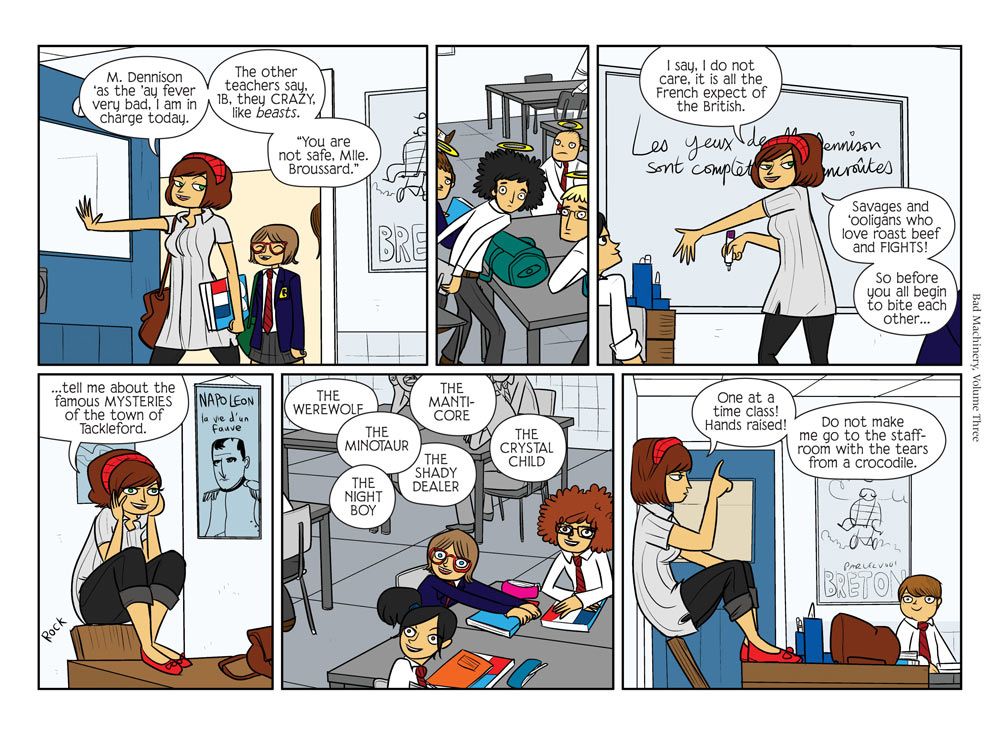

When Allison launched "Bad Machinery" in 2009, the strip presented fans with a major shift in tone from both "Scary Go Round" and "Bobbins." Starring a cast of mystery-solving children, Allison presented clever, all-ages comics in the spirit of "Nancy Drew" and "The Hardy Boys" with a healthy dose of "The X-Files" and Allison's rapier wit. Jack, Linton, Sonny, Shauna, Charlotte and Mildred have been on eight "cases" together, which range from somewhat mundane to absolutely ridiculous -- in the best way.

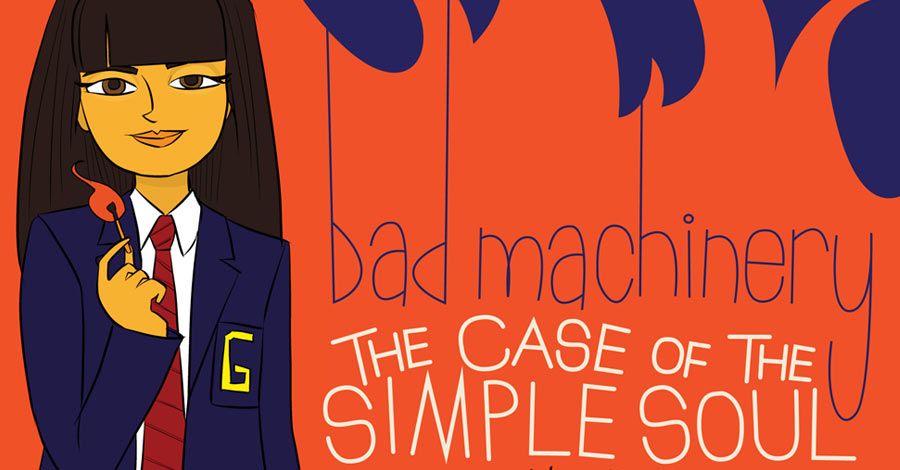

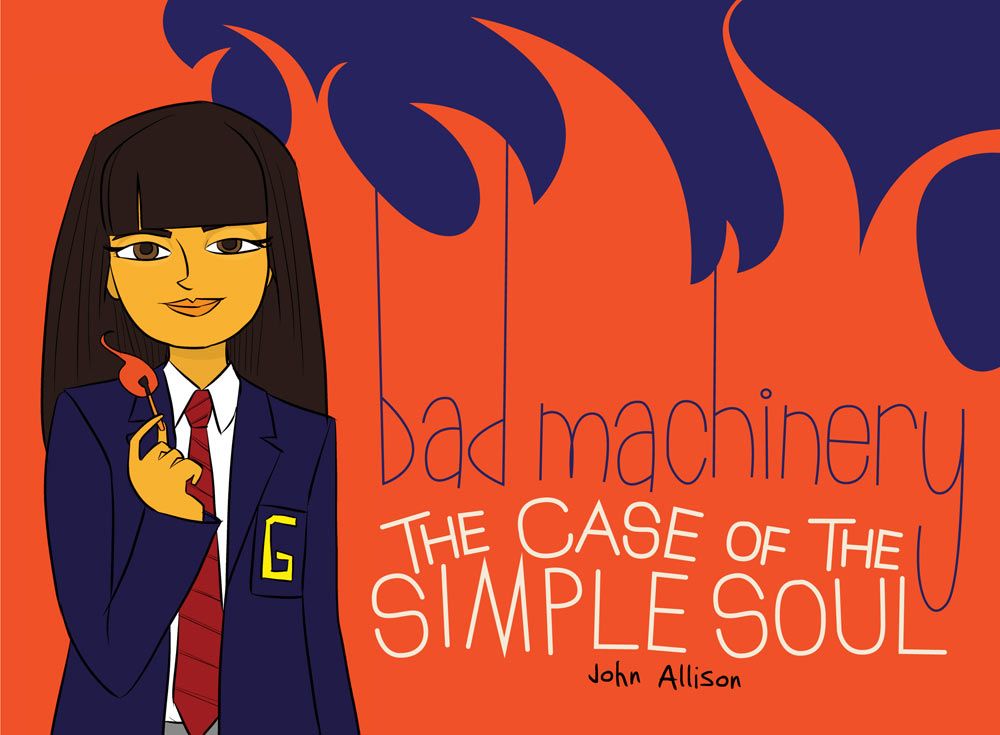

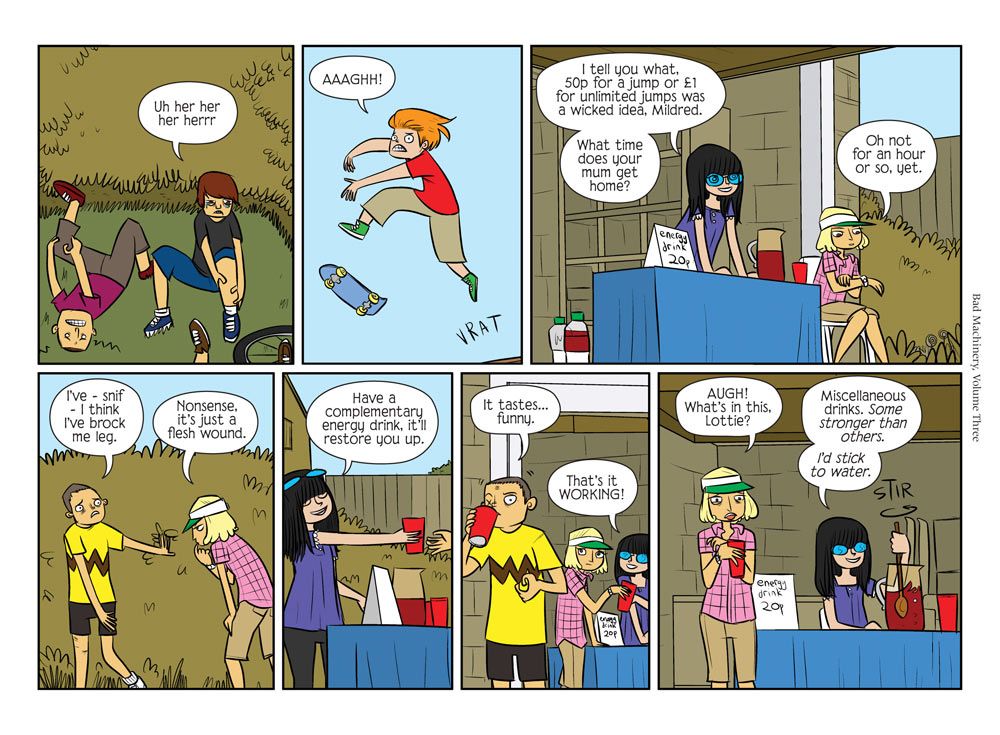

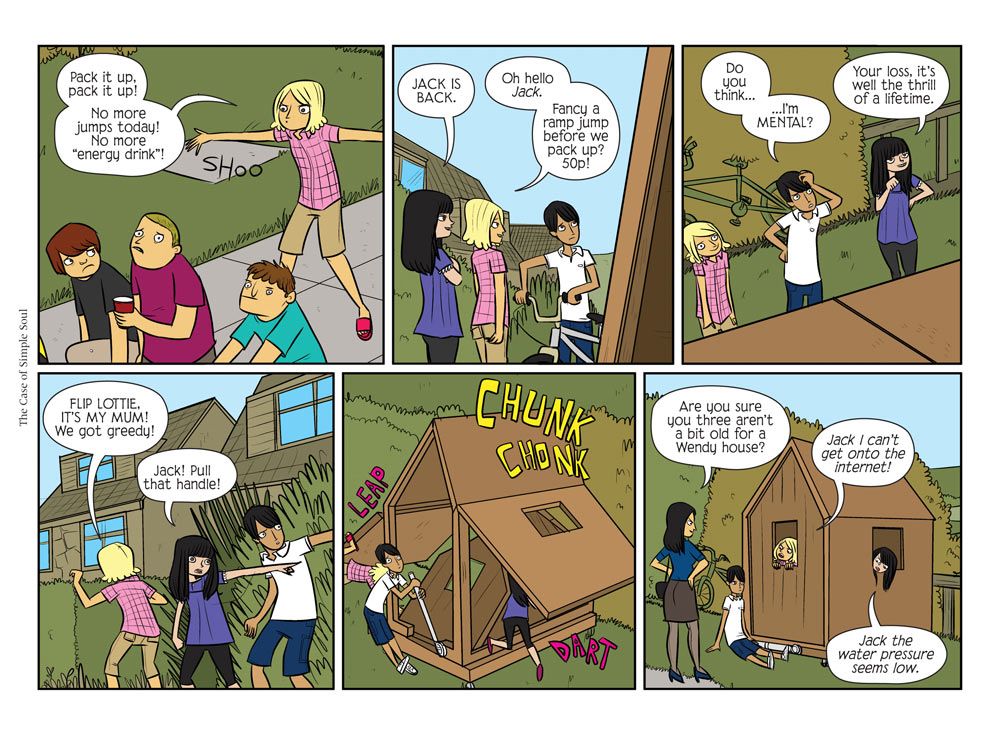

Although "Bad Machinery" recently came to an end online, a new audience is discovering Allison's work through a different outlet: print. Oni Press is committed to publishing collections of Allison's eight "Bad Machinery" stories in hardcover volumes reminiscent of "Calvin and Hobbes" wide collections. The third collection, "The Case of the Simple Soul," is due in stores December 10.

CBR News looks back on the last 15 years with Allison, discussing his lengthy comics career, including his take on how the atmosphere for webcomics have changed as a result of social media, transitioning from self-publishing to working with Oni Press, how his love of '90s superhero comics influenced his latest work, and much more.

John, the announcement to end this particular incarnation of your long-running comic came as a surprise to many. How long have you been considering bringing "Bad Machinery" to a close?

John Allison: A little while. I created "Bad Machinery," not knowing what it would eventually become. I pitched it as a very jolly series aimed at kids, and I'm not sure I hit all the targets that I wanted to. I kind of need to rethink it a little bit and work out where I'm going. There's lots in the series that I see as promising, but it doesn't really fit with the original remit, so I need to put it up on the blocks in the garage, have a look at it, rethink, and then come back. I've been thinking about that for maybe a year, year and a half.

When "Bad Machinery" started, there was actually quite a bit of resistance to it. I've talked about it a few times, perhaps too much. It meant that I was always thinking in terms of, "Will this story be the last one?" after every story. Signs got more encouraging as I went on, but it was never a barnstorming hit. I never really felt like I was producing work that was really hitting everybody and people were going, "This is great, this is the ultimate thing." There was always a sense where I was looking at it to see if I could refine it. I felt the work was good, but I wasn't exactly sure if it was hitting the targets that I had set out to hit.

For years, at least since "Scary Go Round," you'd been self-publishing print copies of your work, shipping them out yourself. What was the impetus to go to a traditional publisher like Oni to do full print copies of "Bad Machinery?"

I think I was just sick of the sound of my own voice, if that makes sense.

[Laughs]

I'd met Oni at SPX, I'd sat next to James Lucas Jones, and I really liked him. They seemed to be nice people and they put out work that I really like from a lot of authors that I thought were really great -- Bryan Lee O'Malley, Sam Keith and Hope Larson -- people whose work I really loved. I knew they were interested, so when I was looking to shop "Bad Machinery" around, I thought that was a good place to take it. You can't ask for any more than people you like and respect that have done work with other people you like who have nothing but good things to say about them.

I wanted to work with a publisher to get work out wider. I was putting things in envelopes or preaching to the choir, if that makes sense. I wanted to reach a wider audience and a publisher was the best way to expand upon what I was already doing.

Do you feel you've found that wider audience since the books have started to hit the market?

Well, because my publisher is American and I live in the UK, I'm limited to how I can get on the road and do things. I know the work's found a lot of readers through libraries. That's an audience I never would have access to. [Oni] works hard to get things out into all kinds of channels that I had no concept of. I'm one guy sitting in a house making comics. My marketing powers are very weak. I was at the point I needed help, and they gave it to me. I was very grateful for it.

The print copies are very reminiscent of collections of traditional newspaper comic strips, and certainly offer a different experience than reading the comic online. Is it important to you for readers to see your work from a different perspective when reading it in print?

The format was in the hands of Oni. I am conservative in terms of the way I'll produce things. When I was self-publishing, I was paying for every square inch of paper. The price of the run went up if you decided you were going to do a beautiful, huge book. My tendency was to make an ugly, small book. That was the only way to go about it.

[The "Bad Machinery" collections] are the same size as the "Calvin and Hobbes" collections, the wide ones. I think that was the intention. It's an interesting format because it demands you just sit down and read it. I don't think you could read it on the bus or the train. It's a proper library book. [The format] was all on Oni. I would have made it smaller, perhaps to my own determent. The way it's come out, it looks magnificent -- French flaps and all, it's a really handsome book.

How important is it to you for your work to translate well to the printed page? What's the process of that like for you?

Well, it's probably the most difficult part of my job. I work on the Internet. You're preparing work a certain way for the Internet. You're making comics to be read day by day. When you put them in print, there's an immediate disconnect between the staccato nature of publishing on the Internet as a daily format, and making a nice book that reads well page to page.

I'd done three of these stories before I'd gotten the book deal, so I had no idea in what format they would emerge. I've thought more carefully about that in each story, about making the transition from page to page. When I do the books, I take the webcomic, I have it all printed out, I look at it and I just go over it with a crayon, marking where pages don't go into each other in a smooth way. Where they don't, I'll cut the pages in half, put new panels in to make the transition work, put a nice splash page in where I didn't have space or time to make a nice, pretty transition between pages. The day between two comics is your transition [online].

You've been a webcartoonist for over fifteen years. You've had the opportunity to see the landscape of webcomics change and see the medium evolve. How has the landscaped changed since you began the original "Bobbins" in 1998?

Well, it's funny -- my audience has stayed with me for the large part, and I feel very lucky in that. But the audience of webcomics has changed. It grew to a certain point, and then social media shrank it. Webcomics were something that people could toy around with at work, when they were just messing around, they could check one of their comics. When they were writing an essay at college, they could have a look at their comics for ten minutes. Facebook fills that gap. Tumblr fills that gap. That time, a little bit of the user's time has gone, and it was some of the space that webcomics occupied.

You haven't lost your core readers, but the casual readers who were just tooling around at the edges have gone, and that is the biggest way in which webcomics have changed. I would say everybody's audiences have calcified, if that makes sense. It's harder to put on those casual readers now. There are still breakout hits and things that appear out of nowhere and gather in an audience, but the great body of webcomics readers is not growing in the way it was in 2003, 2004.

That's the biggest way webcomics have changed, not so much as an artform, but in the way they're competing with all the other very quick, bite-sized attacks on people's leisure time and goofing off time.

When that webcomics boom in the early 2000s happened, there was a lot of talk about how creators would monetize that format, how they would make it profitable. You started a subscription service for "Bad Machinery" over the course of the last year. How do you continue to make this job profitable?

It's like any business, really -- the landscape is constantly shifting under your feet. It's like tectonic plates. Occasionally, there's a little rumble, you hear it off in the distance and you think, "I won't worry about that." Eventually, the ground opens up and maybe it swallows you up, your house falls down -- that's what the business of webcomics is.

At first, we all made t-shirts. It was easy because people were buying a lot of printed t-shirts at the time, and it was harder to get clothes that weren't mass-produced. Slowly but surely, other people moved into that area who were bigger -- and again, sucked some of the oxygen out of the room. Everybody started making t-shirts and all of a sudden, you couldn't really keep yourself alive selling t-shirts anymore. You always have to have your eyes open for the main chance.

I've been lucky in that a lot of times, I've been slightly ahead of the curve, and was one of the first people to make things. I'm sure that's part of the reason I've survived -- it was simply that I spotted little gaps and ways to do things before other people did. You always have to be aware that whatever you're doing may not work six months or a year from now, and you have to be ready with something else. You can't rest on your laurels for a minute because otherwise, you're just the mom and pop store that gets squished by Walmart when they open up across the road. At that point, you either end up working for Walmart or you're dead. That's pretty much how I operate. [Laughs]

Do you find working that way to be stressful?

It's only stressful in the way that being self-employed in any field is stressful. If you're a self-employed person, you always live with that background radiation of stress, knowing that you've got to get more work somewhere. If you can only do one thing, you're at a disadvantage to someone who diversifies. If you're a plumber and an electrician and a roofer, then you've got three jobs you can do. If it's raining, you can go indoors and do a bit of electrician work. It's like that. You have to do a bit of graphic design, a bit of illustration -- you have to have different strands of merchandise that you make. In summer, people will buy t-shirts. In winter, they're not going to want to get their arms out -- it's cold. You just have to have a broad portfolio of things you can do. You have to have a full quiver of arrows, that's pretty much how you offset that background of radiation.

I've been self-employed for eleven years now, so I have a reasonable expectation that something will come along as long as I don't rest on my laurels.

Did you ever think these characters would continue to endure as long as they have?

No. [Laughs] No, no. I had no idea!

When I first started doing comics, I did it in comic strip format because I had no idea how to write 22 pages and make it compelling, but I looked at strips, the American strips, and I thought, "Well, I can do four panels." I did it two days in a row and I thought I'd try three. I'd done a week, I'd done two weeks, I'd done six months, I'd done a year -- but I had no idea.

There was no sense of the future. It was a hubristic act to think I could make it in comics at all, and I don't know where that self-belief came from, to be honest. I think it was partly desperation, partly self-belief, but it's partly bloody-mindedness.

"Bad Machinery" was certainly unlike "Bobbins," or even "Scary Go Round," though it took place in the same world with many familiar faces showing up. What was the draw for you to change gears?

It's just about challenging myself. "Bobbins" in its original form ran for four years, I think. Then "Scary Go Round" ran for seven. Every time I'd wanted to change, people could look at it and say, "This is just a continuation of the same thing." I could have called it "Bobbins" all along and the cast changes like it does on "ER" or a really long-running TV show. But those changes in name are a line in the sand, and the slight changes in settings are for my benefit -- I can say to myself and say to my readership, "We're doing something completely new, now." It helps me psychologically. I don't want to keep digging away at the same old rut and doing the same thing and telling the same joke, using the same tropes over and over again because it's a little maddening. I'd like to think I will have gotten somewhere different from where I started out. That's why I change gears like that.

It would be nice to get new readers, it's nice to become more popular and successful, but I've found the opposite is true [when I shift]. It's more jarring for the readers. It's exciting for me, but [readers] are a little bit nervous when I make a change. I've made so many changes over the years that people have gotten used to it, but I think it partially down to whittling down the audience to people who believe in you rather than the casual who aren't really invested in me as a creator, but rather the characters that they like.

You'd been focusing on the early lives of your characters from "Bobbins" and "Scary Go Round" in "Expecting to Fly," but one of the most fun aspects of the story was your formatting it like an actual comic from the 1990s, going so far as to make up a whole line of superhero comics. Are you a fan of those superhero comics from the 1990s?

Well, the '90s is when I was reading superhero comics, which is why I made it. The content is set in 1996, because that's how I got the ages to line up. But the comics I was referencing with the Bullpen Bulletins type-page and the subscriptions page were a little bit older -- they were the comics that made me excited about comics every month, excited to go down to the comics store and buy them, and get my little installments of these stories. I wanted to pay tribute to that feeling more than anything, the feeling of buying the pamphlets and being excited about what would happen in the next month. That got superimposed on top of this story because I wanted to do a nine-panel grid.

I haven't kept many of my superhero comics, just a few. I gave a lot of them to my friends' children, because I thought they would get more out of them than I would reading them for the tenth or eleventh time. I superimposed all those feelings together and just tried to get a feeling out of it. I wanted people to get the same feeling I did about comics when I was 15.

Why go through the whole process of creating a fictional superhero world? The synopses were pretty detailed. Was it just really fun for you to go through and do that?

[Laughs] I have not enjoyed myself that much for a long time, creatively speaking. I can't even explain it -- it comes out of nowhere. Sometimes, it's a lightning bolt that comes out of the blue, and it's like I'm flying when I'm making something like that. The feeling of adrenaline and pure pleasure -- it's like being a kid at a birthday party, that level of pleasure. It's the sort of pleasure that as an adult you get through drink or whatever -- but that feeling of not enjoying myself more, that I could not be having more fun.

The first time I gave the titles for the subscription ads -- and a few of them, I just made as specific jokes just to make my friends laugh. I knew two people would get them. Then, I made the Bullpen Bulletins page and I was writing explanations, thinking to myself, "My God! I think I'd read this! I don't think anyone else would read it, but I'd read it!"

When I was doing the second issue, I thought, "I can't do the same jokes again, so I'll flesh some of these out a little bit." Before I knew it, I was thinking, "I could do a whole issue of this! I could do letters, I could do --" but realized that I'd better not do that for six months. There's a point where I'm the only one laughing at the joke, and I think it would have reached that. But I could have done whole issues of those things by the end of it. My imagination just came alive.

When you originally moved to "Bad Machinery," you mentioned that it was to re-focus and attempt to broaden the appeal of the strip. As you begin to move on to the next chapter of this world with a new online strip, what's your new goal?

To build a foundation that will last another five or six years. That's all I can do, really. I can only think in terms of a five year plan. "Scary Go Round" ran on a bit long -- it probably ran two years too long, and the last two years were me just in a waiting room, waiting for what comes next; getting some things right, trying longer stories and building the muscles that made "Bad Machinery."

I think the focusing worked. "Bad Machinery," for all it wasn't quite the romp that I thought it was going to be -- it turned into a more thoughtful comic -- I'm incredibly proud of it. The characters really came alive for me, and I don't want to leave them behind, so I want to find something that will work for five more years, maybe with a new name, but that takes the strengths of what I've learned and builds on them again. Something that makes better books, keeps the characters alive and tries new things. Younger readers that came to the series in "Bad Machinery" won't feel betrayed by it, but at the same time, they'll feel they can move on with it rather than sticking with a series that they've outgrown. They get a two-tiered solution. It'll be "Bad Machinery Plus," a souped up model with a few more tricks -- fancy upholstery in the car, bigger wheels, chrome rims -- but at the same time, keep the feeling going and grow it.

Plus, for those that miss "Bad Machinery," there are always the print collections.

Yes, there are five stories still to go, I think. I've done eight "Bad Machinery" stories, and Oni seemed keen on still putting them out. I'll start work on the fourth one very shortly and the third one's out in December.

I think every book's had about 30 new pages -- maybe 20 or 25 -- of story. I have fun; if there are eight pages left to fill out the book, I'll give you eight pages worth. You don't get sketches from my sketchbook, I'll come up with some new ideas and just give free rein to whatever madness strikes when you're up late trying to do loads of extra pages.