Minigames are everywhere and in every type of game. From Guitar Hero-style rhythm jamming in the adventure game Night in the Woods to the Pokémon-esque fighting in Dream Daddy, minigames are a common option to increase game length or experiment with different play-styles. But minigames aren't only moments adjacent to the main narrative -- sometimes, minigames can be art.

Minigames provide opportunities for video games to branch out from their established mechanics and aesthetics. Because they're usually so short, there's no time for tutorializing or building, so they can be great places for tiny gameplay gimmicks. Often games accomplish this by relying on standards of video game history, using styles that they think most players will be familiar with like Pac-Man or Tetris. If done effectively, changing up the gameplay can add variety and make the game more interesting, but more often than not this switch in format and style can be jarring.

Sometimes, however, minigames work to reinforce a game's aesthetic, to pull the player in deeper and connect meaningfully with the larger game. Even minigames that are unsuccessful at preserving the larger feel of the game can contribute, if not to the game itself, then to the broader world. Here are some minigames that got it right that show why minigames can be so cool.

Spooky's Jump Scare Mansion

Spooky's Jump Scare Mansion tries its best to scare players in ways that are sometimes cute and sometimes terrifying. Plywood cartoon cut-outs of spiders and pumpkins will pop out from the wall to elicit one of the titular jump scares, but terrifying ghosts will sometimes appear behind a player and attempt to follow them through a room. Having worked so hard to create an atmosphere that is both cute and spooky, the game is loathe to let that aesthetic go for a minigame. Rather than introduce a completely new feel or take the player out of the environment entirely, Spooky’s Jump Scare Mansion provides an in-game arcade that imitates the larger aesthetic of the game.

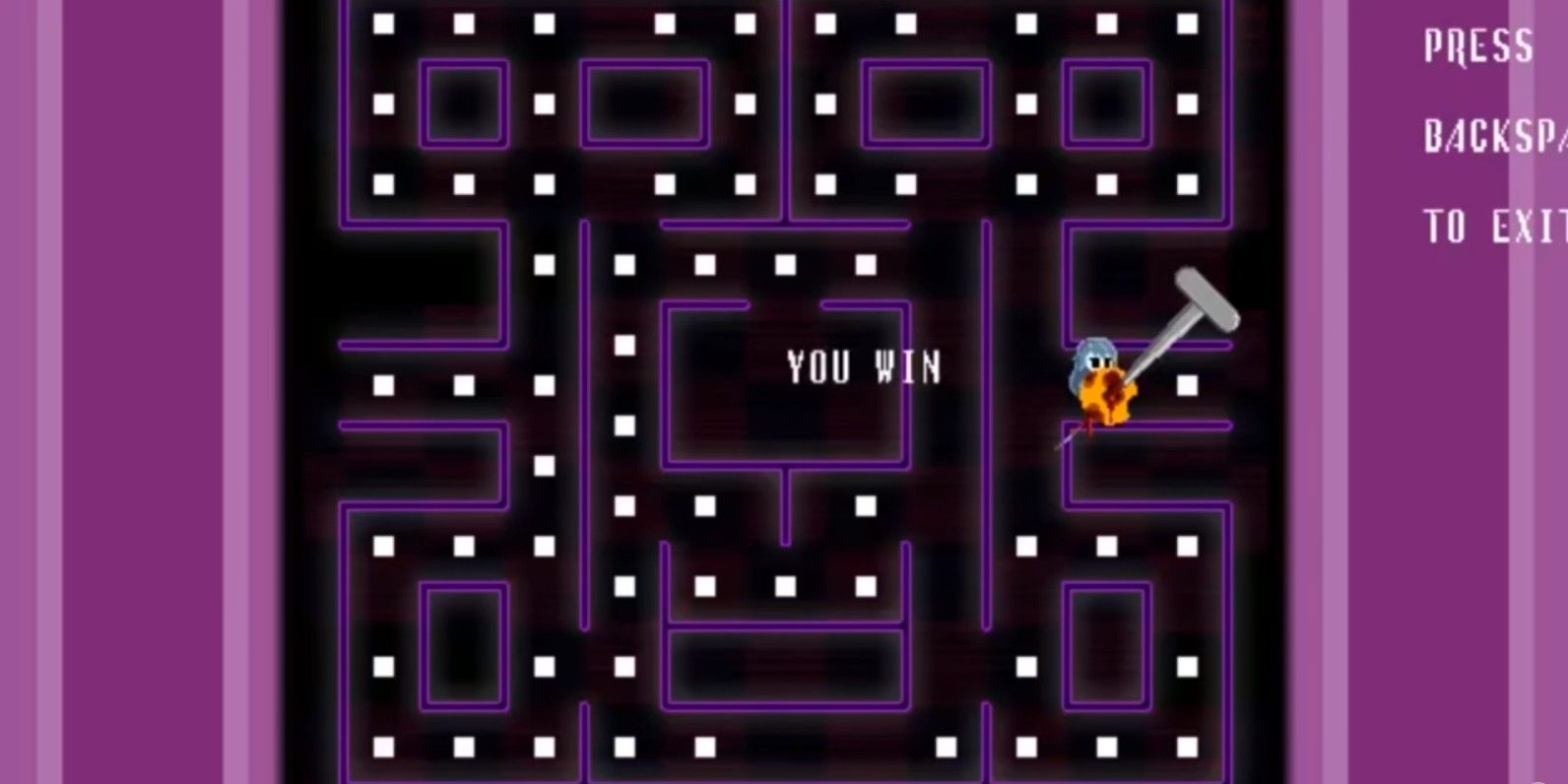

Spooky's version of Pac-Man, called "Mrs. Spook," has users play not as the titular large-mouthed friend, but as one of the ghosts that normally chase him. When the player/ghost catches Pac-Man, instead of the usual opening his mouth wider and wider until he disappears -- a fairly horrific death in its own right -- he is impaled on a giant nail. "Mrs. Spook" seems like a simple break from the constant anxiety of the larger game.

While "Mrs. Spook" does give the player a moment to mentally recharge before diving back into the onslaught of scares, it never lets the player escape from the general feel of the game. From the moment the player futilely tries to pilot Pac-Man around to his gory death, the minigame tells the player that this game -- much like the larger game -- will surprise them in delightfully violent ways. "Mrs. Spook" is an example of a minigame that highlights the work of the main game. It doesn't change aesthetic or controls, and the maze-walking of Pac-Man even resembles the game's overall goal of walking through these spooky rooms. The end result is deeper engagement with the environment and a truly artistic experience.

Borderlands 3

Minigames have also been explicitly useful well beyond their context. Borderlands 3 recently released a minigame that asked players to solve real-world sciences problems, unimaginatively called "Borderlands Science." The game populates a two-dimensional grid with four different types of tiles, looking more like a level from Two Dots or even Tetris. Players can move these tiles around the grid by placing bumper tiles with the goal of creating certain patterns in each row.

Ultimately, the game doesn't feel very Borderlands-esque either mechanically or even graphically. But what "Borderlands Science" lacks in cohesive aesthetic it makes up for in real-world value. The levels aren't randomly arranged with tiles; instead, each tile design represents one nucleotide, and their arrangement is based on the strands of DNA within the gut microbiome. As players solve each level, they're actually training algorithms to better align DNA sequences.

Of course, this real-world value isn't felt by players, who are instead rewarded for the time they sink into this minigame with coin, eventually at staggering levels. It's a win-win for players and scientists -- make a ton of in-game money, contribute to scientific progress. "Borderlands Science" is an example of how minigames can be literally valuable outside of their larger context. While it's not the best example of a minigame in terms of cohesion or art, it certainly demonstrates the potential value of this genre.

These games are certainly not the only examples of excellent minigames out there, but they show the wide range of how they can be used to effectively enhance a game. Minigames can be deployed poorly and can do nothing more than break the narrative flow or general atmosphere of the larger game. But when executed well, these tiny moments can underscore everything that is important to a game -- they can be art and, sometimes, science.