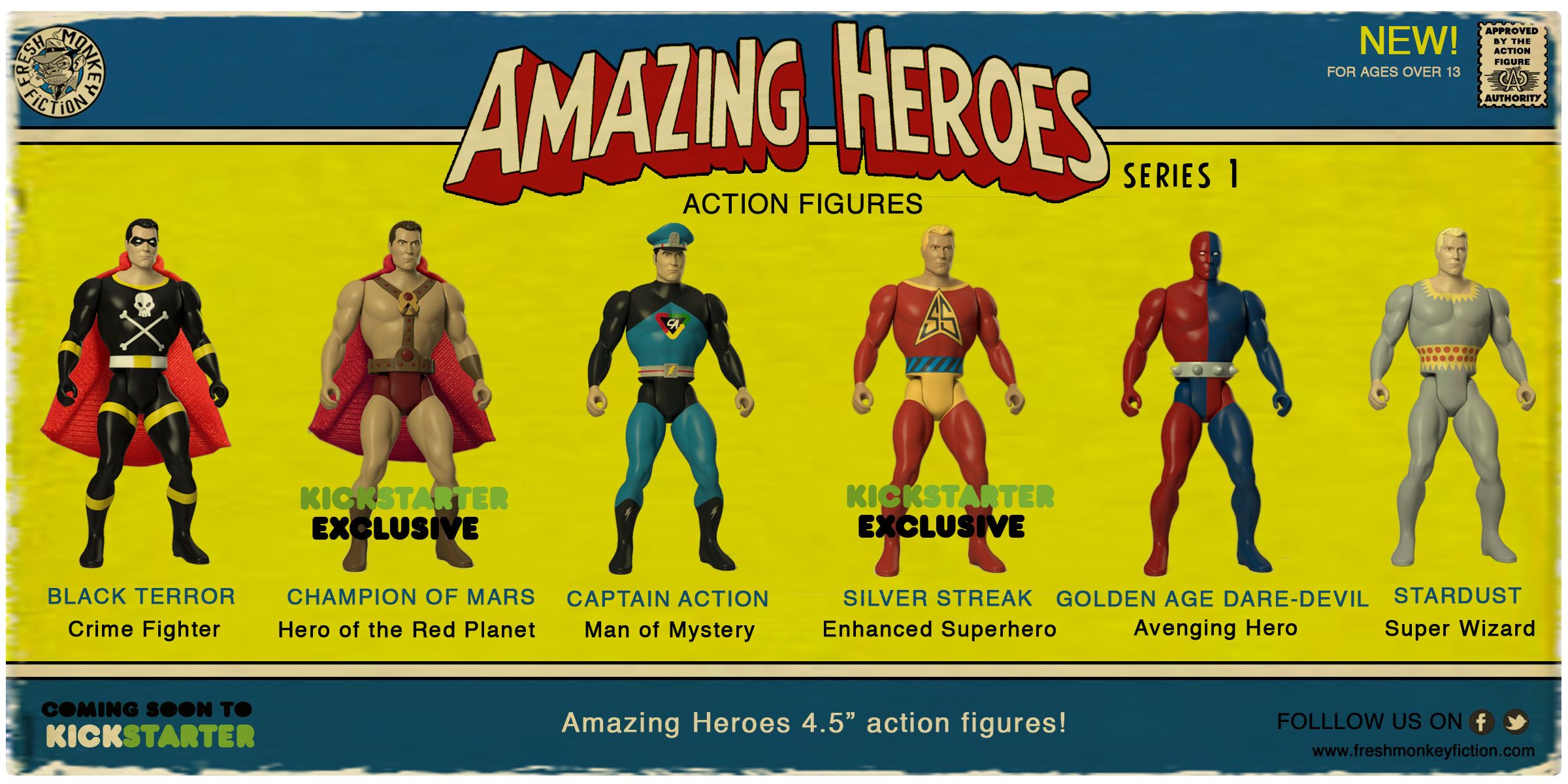

This is the second in a series of essays on the classic characters that are being made into action figures via the Amazing Heroes Kickstarter campaign by Fresh Monkey Fiction. The figures are Stardust, Captain Action, Black Terror, the Golden Age Dare-Devil, Champion of Mars, and Silver Streak. Historian Christopher Irving (Leaping Tall Buildings: The Origins of American Comics and Graphic NYC) kicks it off with a look at Fletcher Hanks’ surreal hero Stardust the Super-Wizard. - BC

It’s 1942. Superman is huge, having already gone to the big screen in the Fleischer Brothers cartoons and dominating the airwaves with the Bud Collyer radio show.

And then, there’s Batman—the dark avenger fighting crime with his colorful kid sidekick.

And then, there’s Black Terror, who falls in between the two of them. While he never took off quite like the Man of Steel or Dark Knight, he still keeps turning up as the superhero who can never die.

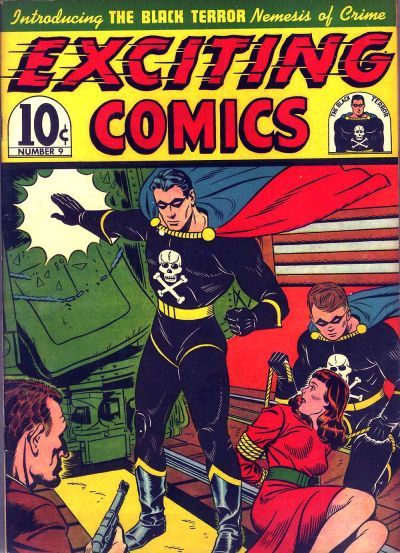

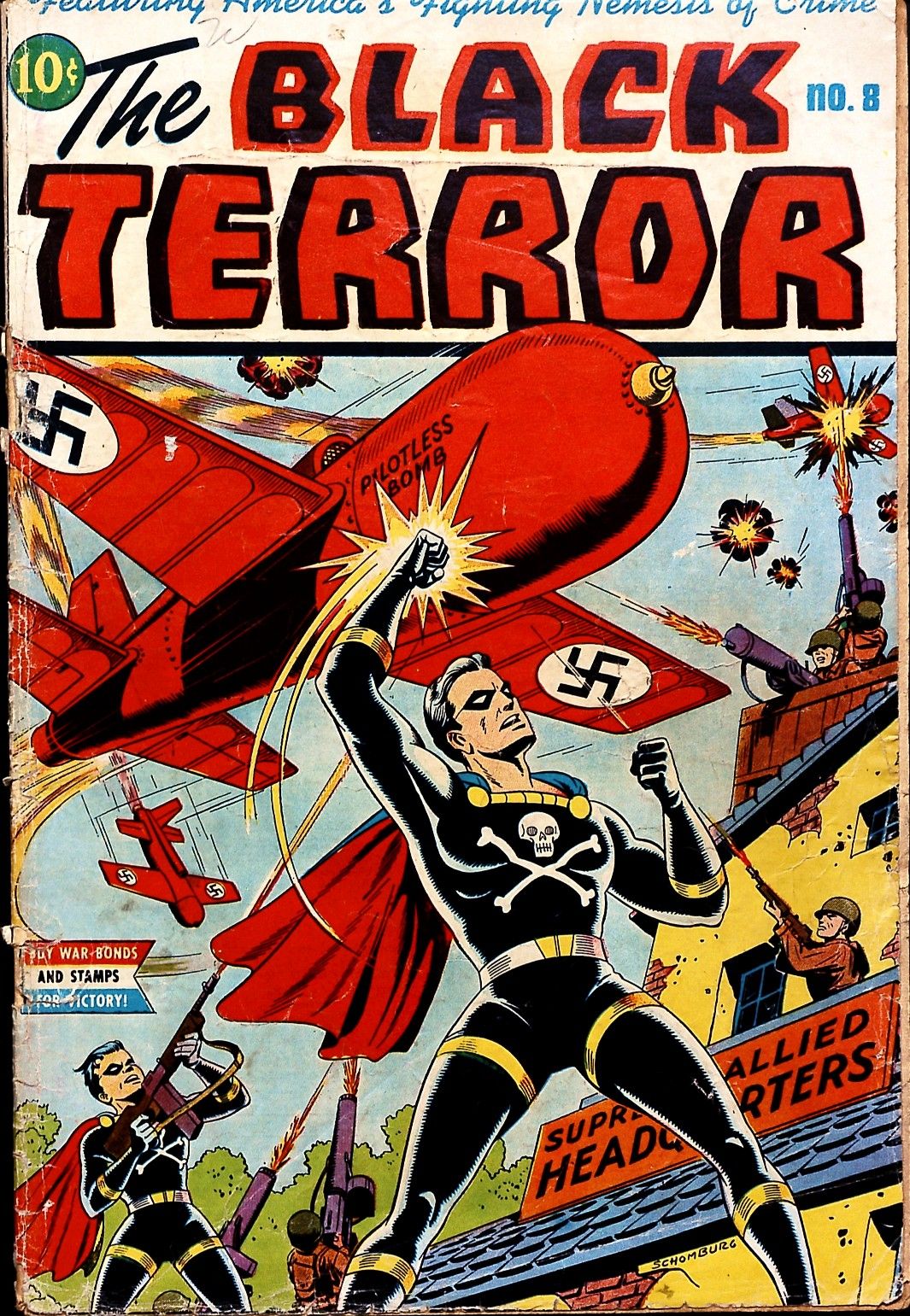

When we first meet Black Terror, it’s the cover of Exciting Comics #9.

His right hand, clad in a gold-trimmed black arrow glove, is swatting a train off like it’s a giant metal fly, the steel crumpling against his palm. His black costume, graced with a skull and crossbones, gold-trimmed boots and trunks with a blue cape with red lining and domino mask balances being both scary and sexy at the same time. His left arm cocked by his side, The Black Terror is looking at a gun-brandishing thug while his kid sidekick unties a brunette tied on the tracks.

It’s like Terror’s saying “Go ahead. I haven’t even broken a sweat yet.”

Inside, it’s a usual Clark Kent scene: timid drug store owner Bob Benton is being leaned on by goons seeking protection money, stammering and shaking because he doesn’t have it. When the thugs kick a neighborhood kid off their car, Bob flies to action—and is soon given the smackdown in front of Jean Starr, the mayor’s secretary, and her asshole boyfriend Rodney Clark, the City Comptroller.

“Why can’t that weak kneed pill-maker take care of himself? Let’s go!” he says before finally beating up the bad guys and leaving the bespectacled Bob (who, oddly enough, looks exactly like Clark Kent in his blue suit) to get chided at by Jean for not being manly enough.

Even though Bob’s “not the fighting type,” the boy, Tim admires him because, even unable to defend himself, Bob stepped in. “That’s why it took REAL nerve…” he proclaims before getting a job offer to work for Bob.

And because he wears glasses and owns an apothecary shop, Bob is working on a tonic for run-down people—which Tim promptly screws up by adding Formic Acid, or does he? Bob, inspired by the strength of the red ants Formic Acid is derived from, plays around with the mixture until he accidentally takes a whiff of it and instantly gains super-strength.

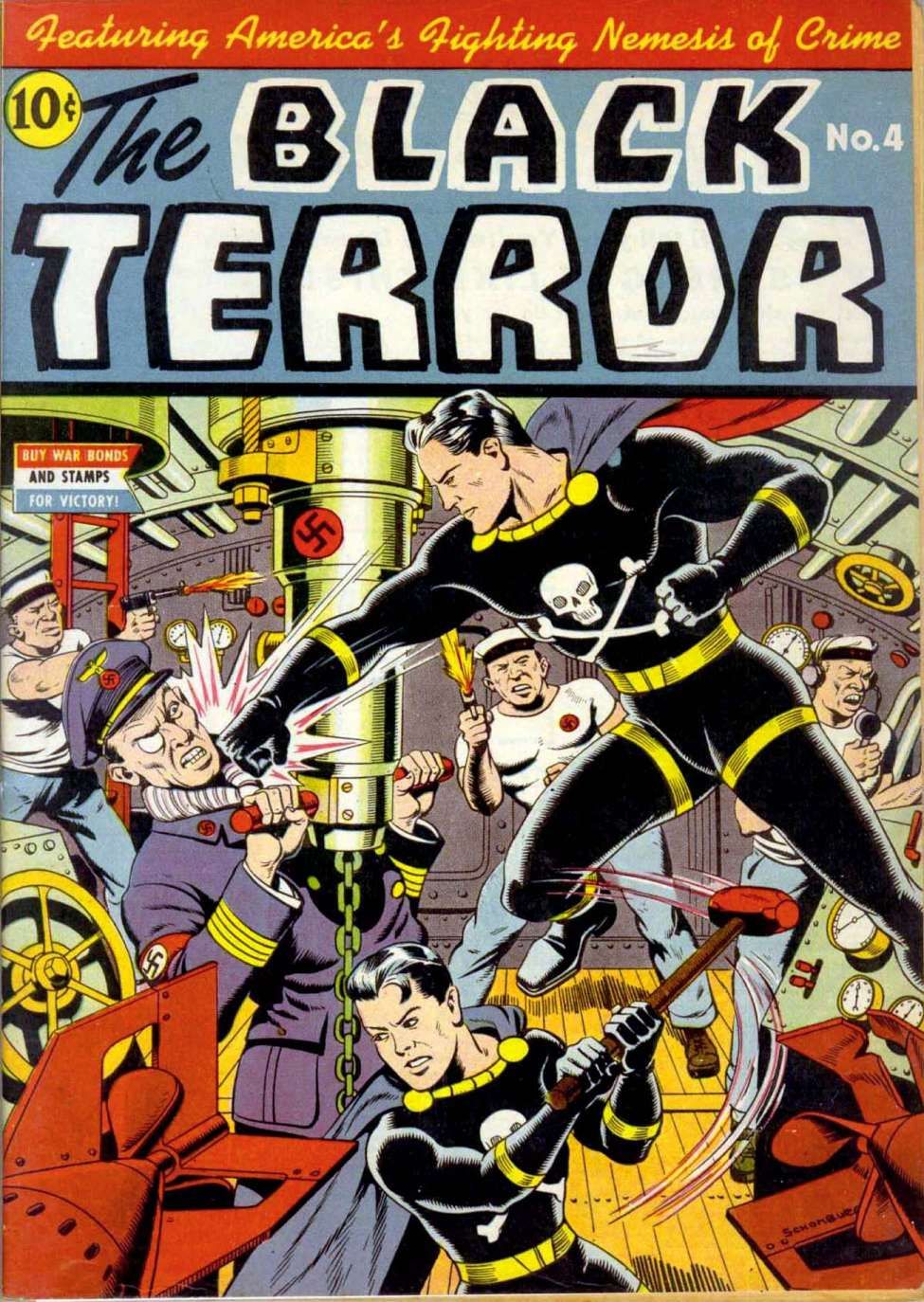

Tim picks up two costumes at a costume shop, on Bob’s orders, and Bob changes into the Black Terror when the heavies come to collect the protection money. But he’s more Superman than Batman, taking punches to the jaw without effort and stopping a train without breaking a sweat. Tim even shows up in his own costume, having snuck a whiff of the vapors in secret.

And so it starts.

The writer is Richard Hughes and the artist on the debut story was a Gabrielson, his first name might have been Dave, might’ve been Don.

The publisher is Better Publications, one of the comic book lines (along with Nedor) as part of pulp magazine publisher Standard Comics. It was typical back in the waning days of the Depression for pulp publishers to hop on the comics bandwagon. Black Terror will be the biggest of the Standard/Better/Nedor superheroes.

The Black Terror gets more inconsistently super by his second appearance: a bullet knocks him out and a fall from a few stories up may—just may—make a dead blob of black clad superhero on the sidewalk below. Of course, he’s still strong enough to swing a car, single-handed, by its fender.

He still subscribes to the Superman/Clark Kent formula in his Bob Benton identity, playing the wimp in the face of mobsters and thugs and using the Black Terror to get back at Rodney Clark—giving him a black eye for each of his first two appearances. Then, Benton does something Clark Kent never would do as Superman, that a normal person would.

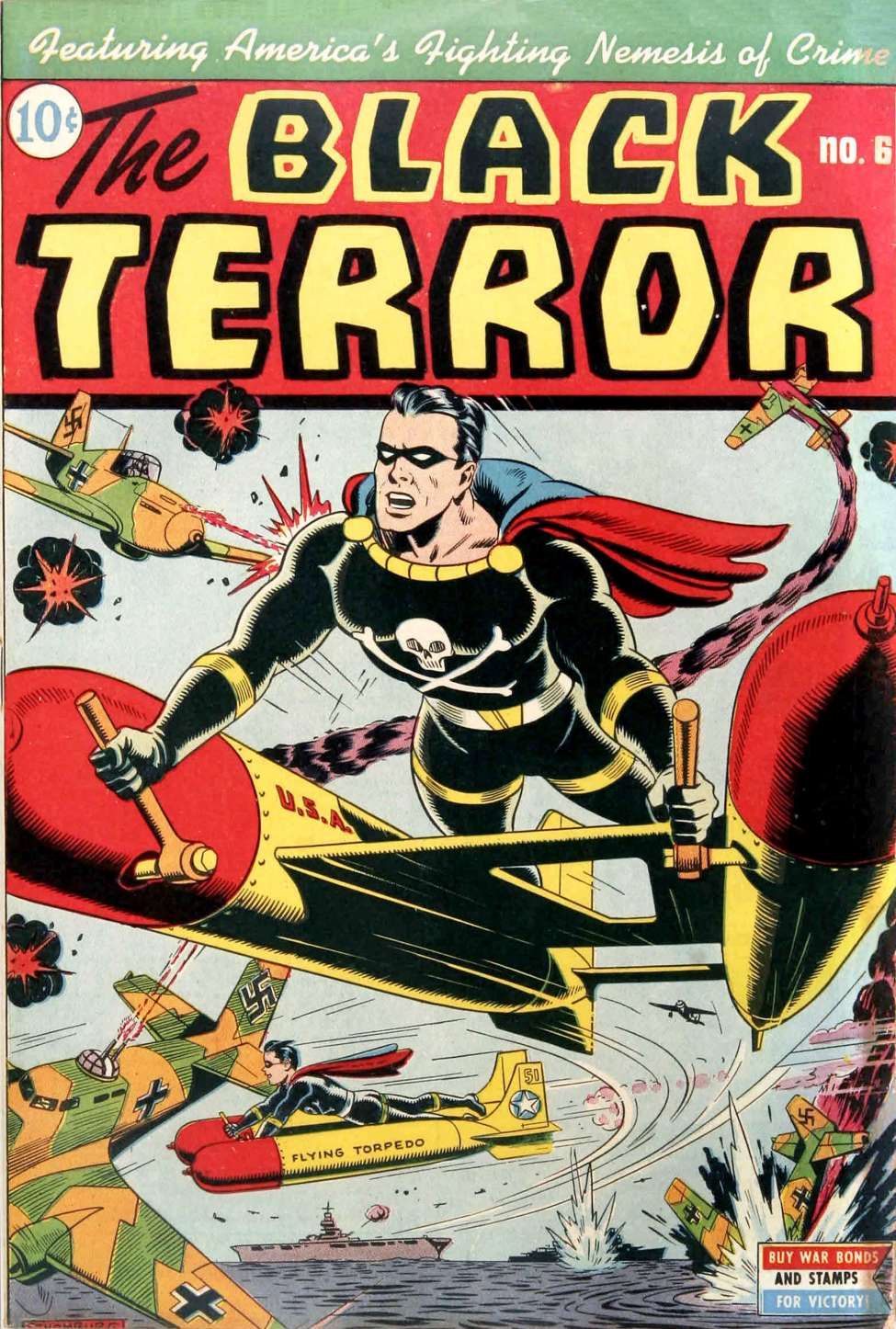

Clad in his Black Terror costume, he goes to Rodney’s house to beat the crap out of him after getting his fill of him as Bob. Rodney just stops appearing, yet Jean sticks around, still mooning after Black Terror with Benton an unrequited milksop, but even she disappears. By wartime, Tim goes from brunette to blonde, changes from boy to teen, and the pair switch from fighting mobsters to Nazis and the Japanese.

The art, no longer by Gabrielson or Albert Wexler, goes downhill. Black Terror starts to look less barrel chested and more pudgy; the figures cram into the panels less proportionately and far more awkward.

Then, beautiful things happen to The Black Terror. Artists like Sheldon Moldoff, from Hawkman (and later Batman), and Mort Lawrence take over the art chores. In 1948, artists Jerry Robinson and Mort Meskin take over the art chores on some of the Terror Twins’ adventures—perhaps the most iconic run of any creative team on the book.

By this point, the Terrors are mostly daytime adventurers, but even when they run around in broad daylight, the blacks of their costumes work with present shadows to give a sense of danger. Their Terror is lithe, acrobatic, and swashbuckling. They’re no longer powerhouses like in the earlier adventures, but more grounded urban crimefighters (in a city that feels like a small town).

Robinson and Meskin were genius on their individual merits: together, they were the creative team that—sadly—mostly die hard comics history fans are aware of. They’re what happens when you throw two geniuses together.

Jerry got recruited into comics when he was a kid ready to start college the next fall, when Batman co-creator Bob Kane spied his cartoons on a painter’s jacket he was wearing, and asked him to join his bullpen. Using Batman as an impetus to choose Columbia, Robinson joined Kane and writer Bill Finger on the early adventures of the Dark Knight, bringing inky shadows to Gotham, taking the crudeness of Kane’s early pseudo-Gould style and giving a touch more grace and a ton more atmosphere. With Finger, Robinson brought icons like The Joker and Robin the Boy Wonder to life.

Not too shabby for a kid trying to juggle drawing comics with going to one of New York’s greatest universities.

Along the way, Jerry became pal with boxer turned comic book artist Bernie Klein, who then introduced him to Mort Meskin. The apartment they shared became the hangout for the artists of the ‘40s, from Superman’s Shuster and Siegel to the no less talented smaller fry. This brotherhood came to play when Jerry, Bernie, Mort, and other cartoonists spent a snowed-in weekend cranking out a 64-page comic book of Daredevil for publisher Lev Gleason.

But that’s a story for another time…

Meskin made his mark at DC Comics on both the super-speedster Johnny Quick and the gun-slinging modern-day cowboy The Vigilante. To say his work was more dynamic than Robinson’s would be entirely unfair—but to say Meskin had a stronger eye for action and negative space in his design would not be. When the two came together it was the joining of two masters of the art form, both with a penchant for shadow and light.

The Black Terror and Tim hung up their capes in 1949 but, since entering the realm of public domain, have made several comebacks in tons of iterations—the striking black and gold costume maintaining its mystique and appeal through more than a few generations.

More than a ghost of a superhero, The Black Terror remains a swashbuckling two-fisted icon.

Black Terror is just one of the Golden Age heroes that is part of the Fresh Monkey Fiction Amazing Heroes action figure line, up for crowdfunding on Kickstarter now. Donate now to bring Black Terror closer to coming to plastic action figure life for the first time ever.