Alan Moore's "Jerusalem," the visionary comic book writer's first prose novel since 1996's "Voice of the Fire," is an extraordinary achievement. Published by WW Norton's Liveright imprint and billed as a novel "about everything," there is indeed quite a lot of ground covered in its nearly 1300 pages. But, Moore being Moore, it's a very particular version of "everything," and certain interests carry through more clearly than others.

"Jerusalem" concerns itself extensively with language, history, and human kind's movement through the mortal and immortal realms. Its characters -- we'll get to them shortly -- are at once richly developed as well as ciphers, utilized to explore particular eras or states of mind, as well as, all taken together, displaying the unlikely connectedness of all human history. It's an extraordinarily challenging book -- particularly in its morality, which sometimes takes a not-at-all-greeting-card approach to the adage "Everything happens for a reason" -- but also one that rewards the reader for taking the time and effort.

So what's it about?

"Jerusalem" is about life, death and afterlife in Northampton, England, from roughly 800 CE to 2025, plus forays a bit deeper into the past and on to the end of time. Divided into three books (literally for the slipcased paperback; separated by section dividers in the hardcover), the first introduces many of the major characters and settings, among them siblings Mick and Alma Warren of the novel's present-day 2006; Ernest "Red" Vernall, touched by angels and madness in 1865, who passed certain knowledge down to his son Snowy; junkie prostitute Marla Stiles, also of 2006; the tormented but easygoing Freddy Allen, permanent resident of the Ghost Seam, the in-between world where the dead can observe the living and re-live moments from their own lives, but are unable to affect change; a monk who carried out a sacred mission to deliver a cross from Jerusalem to Northampton, on foot, in the 9th Century, and died; baby May Vernall, Snowy's granddaughter, who was too perfect for this world; Henry George, a branded former slave from Tennessee who becomes one of Northampton's earliest Black residents, well-liked and known around town as "Black Charley;" failed poet Benedict Perrit, best known for his strange laugh, also of 2006; the formidable "deathmonger" Mrs. Gibbs, who handles affairs both of birth and death for Northampton; the Master Builders who play billiards (or, rather, "trilliards") with fate; and more. Each of the chapters are told from or near a perspective fitting to the subject of chapter, with appropriate variations to the dialect and narrative. Many of the characters have brief interactions with each other, sometimes across the aeons -- the monk encounters Perritt, Marla accidentally snoops on Freddy Allen -- though the full import of these encounters will take some time to bear out.

Oh, and yes, these are all major characters. No, that's not all of them. And many places around town, including Doddridge Church, could be considered characters in their own right.

Book Two, "Mansoul," could stand alone as a complete novel, setting it apart from the other two large divisions of "Jerusalem." Once again, the narrative shifts between several perspectives, but unlike the first book the chapters tell a single, unified story. Mick Warren, a full-grown man when we first meet him in 2006, chokes on a cough drop in 1959, back when he was known as Michael, and dies. Rather than finding himself greeted by departed family in heaven, Michael finds his perspective shifting to recognize new angles in the corners of the ceiling at 17, St. Andrews Street (Moore's real-life childhood home), and a strange girl wearing a reeking pelt of rabbit skins helping him up into the realm of Mansoul. This higher plane features many familiar but slightly off versions of Northampton locales, as the region is constructed largely of memories and imaginings of the lower realm. From here it is possible to travel to different points along the mortal timeline simply by walking, peering down into life at will. Fleeing, Michael runs into trouble with the charismatic demon "scrambled Sam O'Day" -- in other words, Asmoday -- before reuniting with Phyllis and her gang of urchins, the Dead Dead Gang. His new friends deduce two important facts: Michael Warren will return to life, so they might as well let him play around in the afterlife as much as he likes; and he will play a significant role in a celestial event known as the Porthimoth di Norhan in 2006, which will require him to remember everything that happens to him in Mansoul. Michael Warren, descended from the Vernalls, is of a lineage that rules the margins and angles (notably, angels are referred to as "angles" throughout "Jerusalem"), and two of Master Builders, chief among beings in Mansoul, came to physical blows over a trilliards play for Michael's life. Adventures ensue across many years, characters from book one are rediscovered -- including a surprising turn for Marla in her relative near future -- and Michael sees the development of Northampton from its deep history on down to Cromwell's battles and through to his own present day, on through the destruction of his home in the mid-twentieth century and further to the destruction of just about everything in the mid-twenty-first. He learns that the creation of the Destructor, a giant incinerator that only existed briefly in the early- to mid-twentieth century, caused severe psychic damage to the town that continues long past its own destruction, sucking away hope and memory beyond 2006 and eventually leading to the collapse of Mansoul itself.

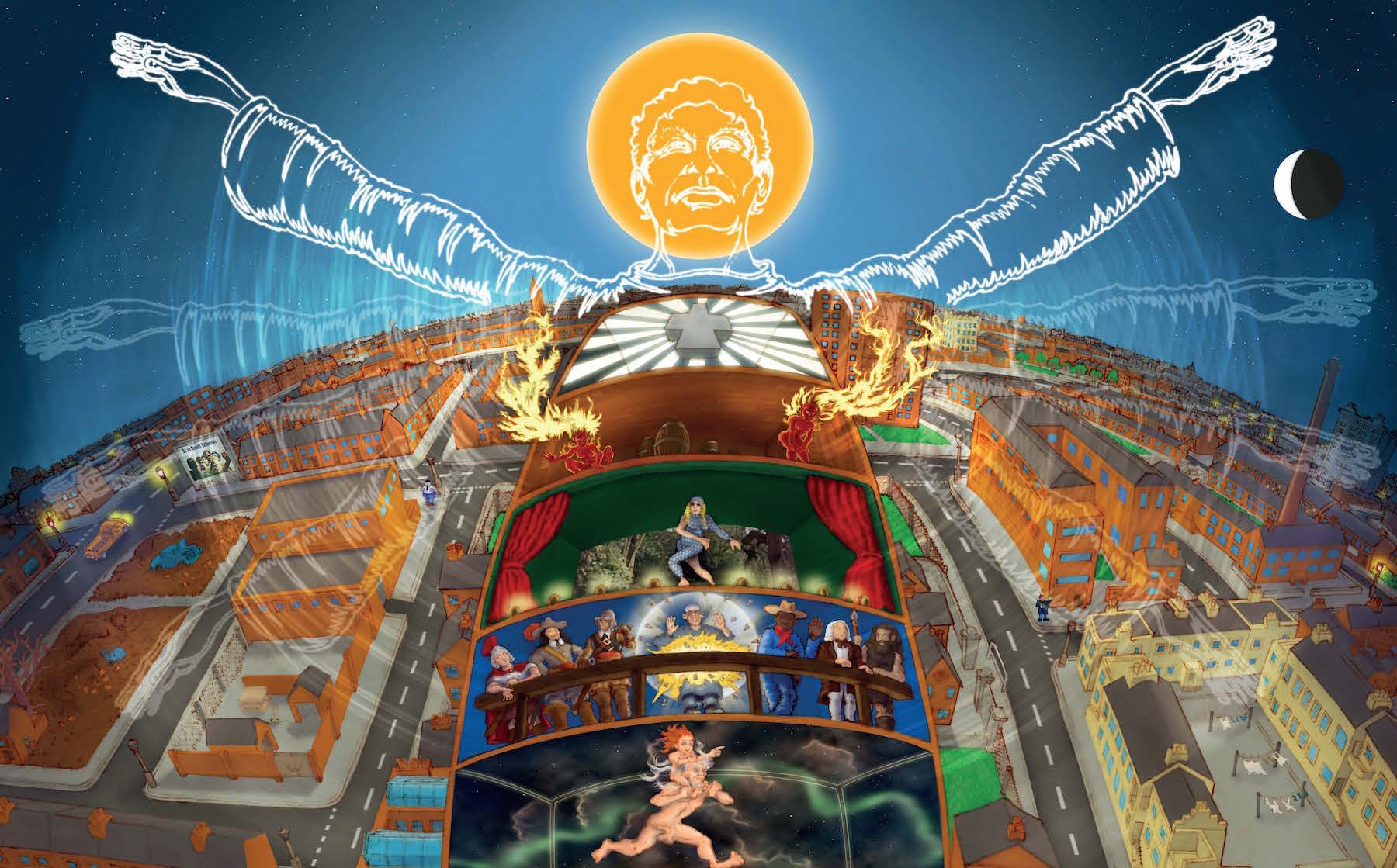

All of this becomes fuel for his sister Alma's art exhibition, which looms large over book 3 and plays a significant role in the Porthimoth di Norhan.

Anyone interested in history should find a ton to enjoy in "Jerusalem." Moore has done a massive amount of research and makes effective use of his source material. The Dead Dead Gang's encounter with Cromwell, Black Charley discovering the truth behind "Amazing Grace," and tragedy of Lucia Joyce all give rise to powerful moments. Moore is understandably on less solid footing for future events -- the flooding in "the twenty-fives," and everything that comes after -- but on the whole he avoids this by presenting what he needs to present and moving on. We know what happens to one significant character after the flood, and we're given highway mile-markers on the death of humanity, but setting the crux of the novel in 2006, around the time he started writing "Jerusalem," Moore largely sidesteps the perils of fortune-telling in an otherwise historical volume.

Oh, and as to more recent history? Moore's wife, artist Melinda Gebbie, turns up several times in the final volume as a close friend to Alma Warren.

"Jerusalem" is also a book fascinated with language. The "angles" speak in compressed bursts of sound, which expand into ever more complex sentences and meanings; other dead folk similarly speak in an elevated language approximating the multiple-meaning amalgamations of James Joyce. When Michael Warren first arrives in Mansoul, he finds himself spouting words that are not quite right -- "It must be a missed ache" -- although still ripe with intention, a speech pattern Phyllis describes as not having found his "Lucy-lips." In Joycean fashion, even this has multiple meanings, the most obvious having to do with lucidity but also referring more directly to the institutionalized Lucia Joyce, the "Ulysses" author's daughter. Moore adroitly fashions his own language, with its own rules -- the word "wiz" is sufficient to represent "is/was/will be," as time takes on a different dimension for the dead -- with Michael becoming more adept and less when rattled. The angles' language is complex, nearly but not quite decipherable without Moore's translation; it's just a little too compressed, although he takes pains to note that the offered translation is just an approximation of the full meaning.

The fixation on language also applies to form. The third book contains an entire chapter from Lucia's perspective, written in Joycean language. (Be prepared.) Other sections of the third and final volume adapt different literary forms, including an epic poem, a one-act play, and a hardboiled detective story (without an actual detective in it).

All of this said, Moore is not Joyce, and while he appropriates some methods, he does not attempt full mimicry; this has led to some criticism, but the intentions are different. Joyce artfully documented a single day in Dublin in "Ulysses" and created a multivalent epic in "Finnegans Wake," but Moore's aims are different. He elevates Northampton, and with it, its people. Experimental language is a tool, history is a tool. Characters, plot, all are devices to this end.

The morality of "Jerusalem" is aggressively ambivalent, which can make passages in which characters perpetrate or describe truly deplorable acts very difficult to stomach. The one-act play is devastating and brilliant, even though, in terms of plot development, it only provides new information about something the reader already knows. Here, the poet John Clare observes a husband and wife, whom the reader recognizes as the parents of Audrey Vernall, a grandchild of Snowy Vernall who was institutionalized, on a certain fateful night. Clare banters about the developments downstage among the living with his fellow deceased luminaries Samuel Beckett (whom the play seems rather styled after) and Thomas á Becket. While the Vernalls bicker their way toward the conclusion we know is coming, Clare hints around his own guilt, until he finally confesses to his final visitor, Marla, in graphic detail. Marla does not so much forgive him as suggest that his actions were simply what needed to happen, and that Clare shouldn't be so hard on himself -- after all, if a series of violent acts hadn't been perpetrated against Marla and several others, Marla would not have been able to accomplish the good that she did. The extension of this, of course, is the question, well, what does it matter that Marla accomplished what she did? If the maiming of lives is simply a matter of course, what then is the value of saving them?

When asked whether there is free will, a Builder tells the Dead Dead Gang that there is none; "Did you miss it?" he asks, his laughter unnerving them all.

"Jerusalem" is cyclical, and so, too, is this review: this is a difficult book. This is a beautiful book. Everything is essential, everything feeds into everything else. The first four hundred pages are extraordinary prelude to the novel at the middle, followed by a four hundred page denouement. Moore has written a novel about life, an epic that includes some really ugly bits, eloquently rendered, and some transcendent pieces, equally stunning. There is humor, and innocence, and dire guilt. Rape and brutality, and several chapters in a row about birth. Read at your own peril, but do read.

"Jerusalem" is available now as a single-volume hardcover or three-volume paperback.