In "Reason to Get Excited," I spotlight things from modern comics that I think are worth getting excited about. I mean stuff more specific than "this comic is good," ya know? More like a specific bit from a writer or artist that impressed me.

Today, I spotlight Adrian Tomine's brilliant new graphic novel from Drawn and Quarterly, The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist (a play on the famous Alan Sillitoe short story, "The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner"), which offers a strikingly unvarnished look at Tomine's inner thoughts over the course of his career in comics (and, of course, as a man who, over the course of his long career, has become a husband and a father to two daughters). Much of Tomine's work over the years has been in the pages of Optic Nerve, including his most recent, best-selling collection, Killing and Dying, which mostly collected Optic Nerve #12-14. This is an original work and sees Tomine returning to autobiographical comics (which he did so well in 2011's Scenes From an Impending Marriage).

There is a scene in Cameron Crowe's excellent film, Almost Famous, where the band in the film reads the article that the young journalist lead character of the film, William Miller, has written based on his time traveling with the band. Miller is a fine writer and he captured the true human struggles of the various band members and that, of course, is not what they wanted at all. As the lead singer notes, "Is is that hard to make us look cool?" That's the trick, though, as that's obviously not honesty. It is not that people are not often cool, as of course they are, but that rarely is where the most human moments occur. Therefore, it is striking in how much Tomine leans the OTHER way in this memoir.

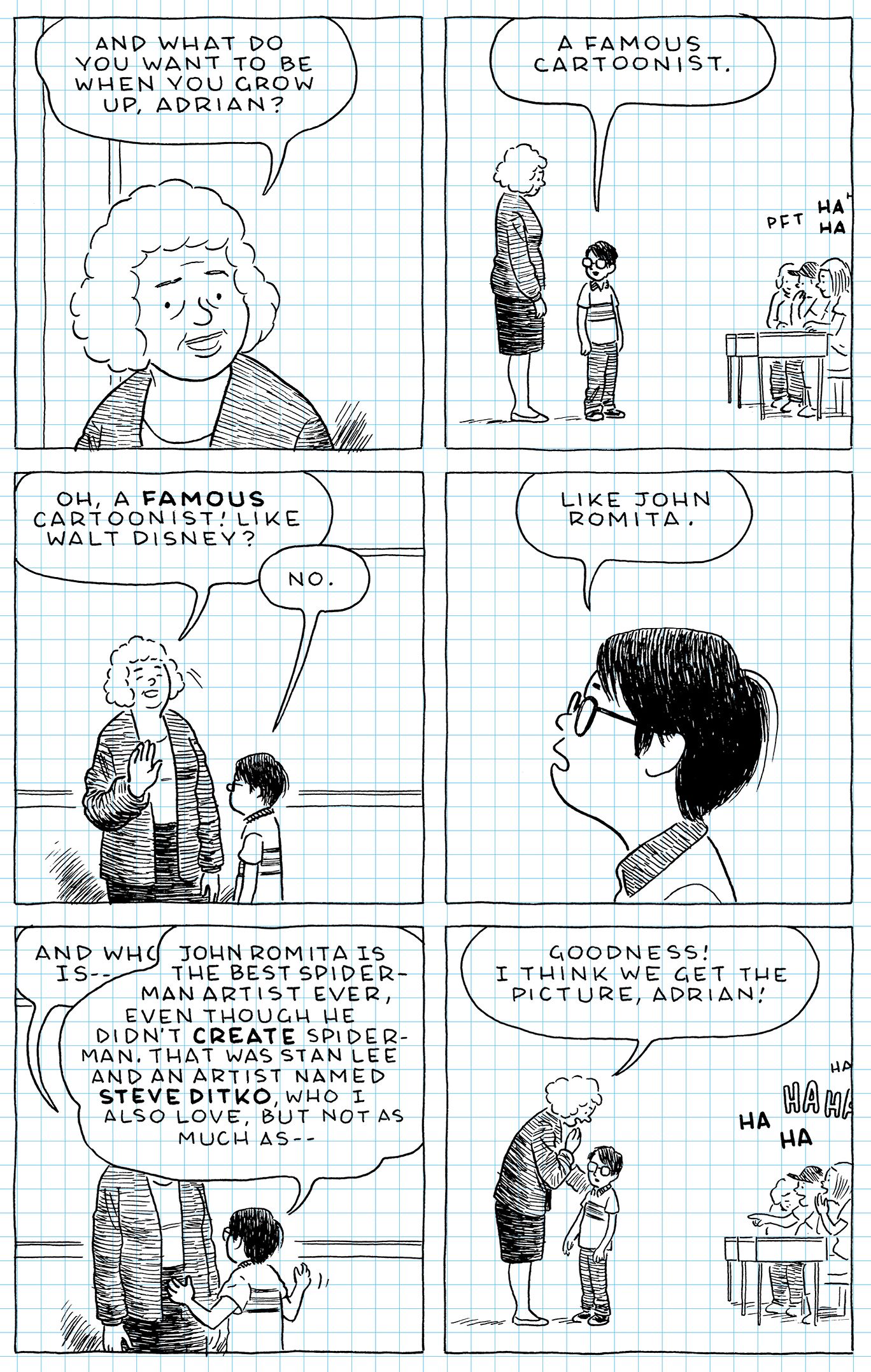

The whole thing kicks off in 1982, when eight-year-old Tomine moves to a new city and is introduced to the class. The teacher asks him what he wants to be when he grows up and he explains that he wants to be a cartoonist. The teacher, naturally, thinks Walt Disney, but young Tomine launches into an overly-detailed explanation for why he wants to be the next John Romita. The other kids laugh at him and he rages at them in response.

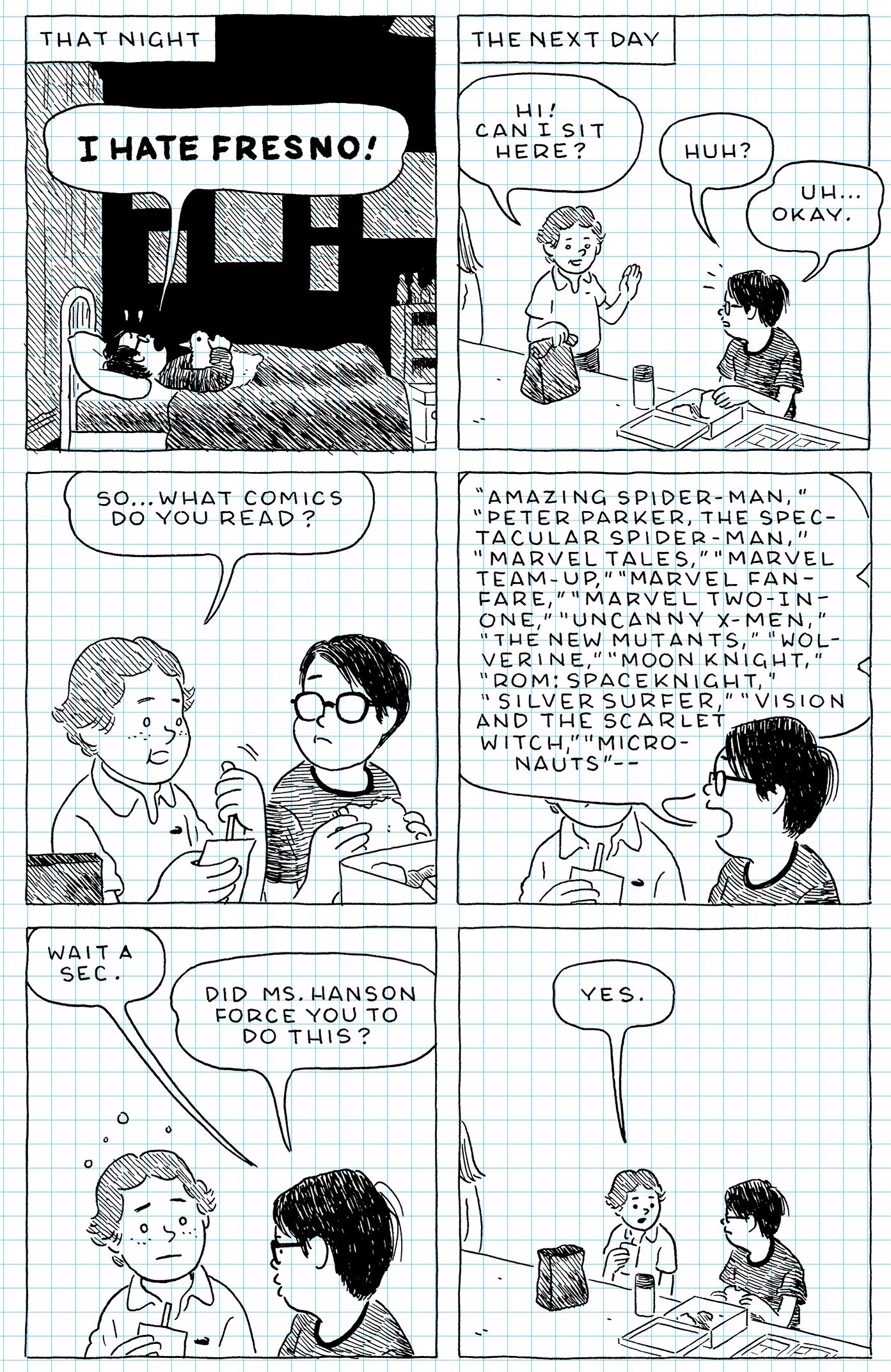

After countless bullying from the other kids, one of the other students reaches out and tries to be nice to Adrian and talk about comic books with him, but the awkward young kid can't just have a "normal" conversation about comics, he has to once again go super in depth about his love of comics and it clearly sets him apart.

This striking opening sets up the rest of the novel, which is about the progression of Tomine's career (and, as his career progresses, so, too, does his personal life). Almost all of us have those inner voices of doubt in our minds, but Tomine isn't afraid to make his extremely visceral and open to the reader. When he attends Comic-Con for the first time, as a "hot" young indie talent flying high off a lot of critical acclaim, he shows up right in time to learn that there has been a scathing review of his work published in the Comics Journal and while Tomine presents a tough exterior to the criticism, he then shows us his actual reaction to the review and it isn't pretty.

In his blurb for the book, Alan Moore applauds Tomine's portrait of the comic book industry, an industry that Moore notes that he can longer be associated with. And Moore's correct, of course, but I think it is interesting to note that much of Tomine's ups and downs that he captures in the series of vignettes in the book that take place over the course of twenty or so years land so well not just because they are familiar to comic book fans, but because they're familiar to people period. In other words, Tomine's stories resonate because they are just so human and relatable overall.

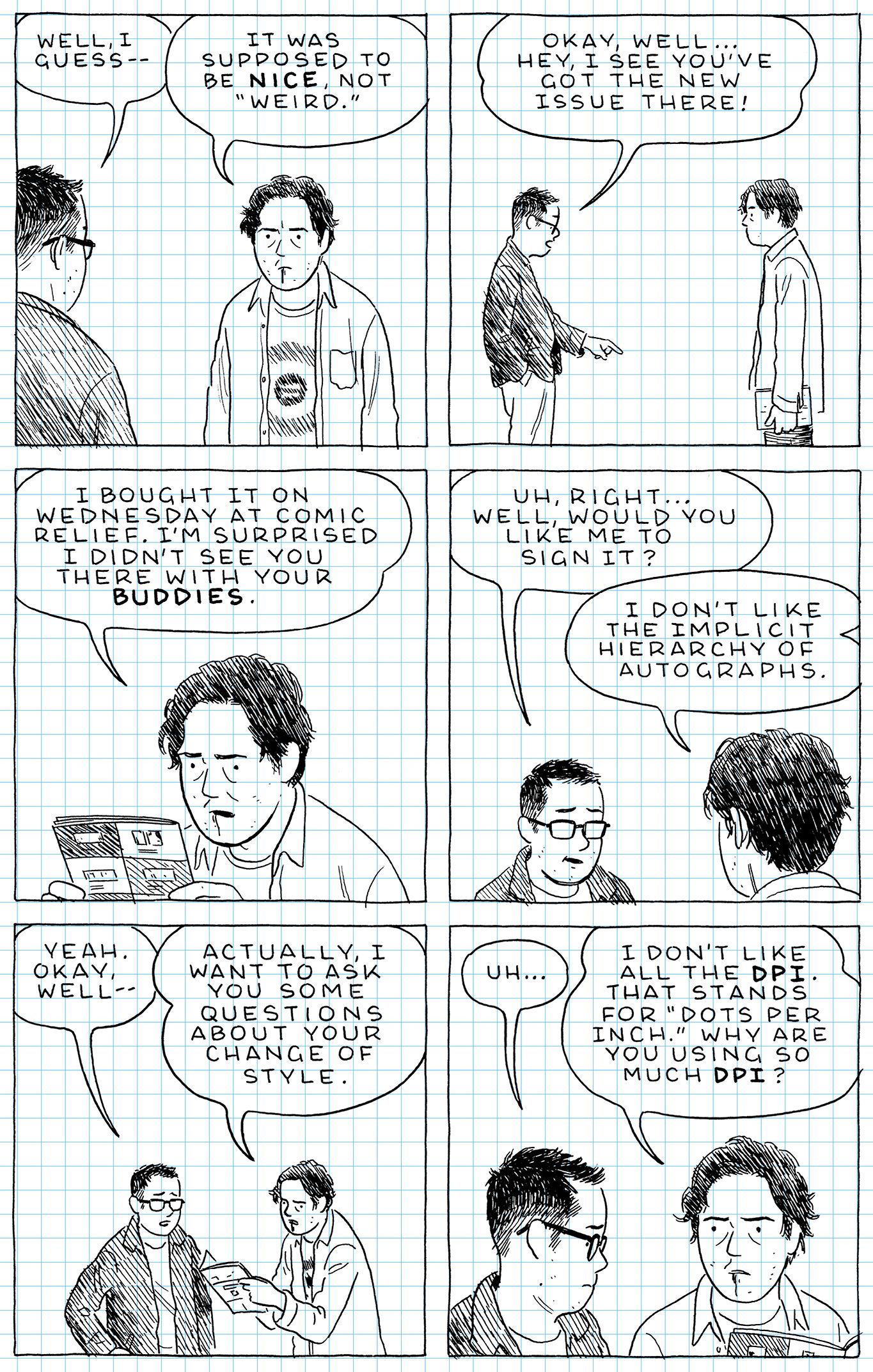

That said, there are certainly aspects that specifically appeal to comic book fans, like Frank Miller not even to bother to pronounce Tomine's name when Miller is presenting an Eisner Award that Tomine was nominated for or the comic book shop that Tomine is doing a signing at with his fellow Drawn and Quarterly great, Seth, that is totally devoid of fans coming out for the signing. There is an amusing experience where Tomine acquires an obsessed fan, but when he tries to confront the obsessed fan, it does not go the way that Tomine expects....

Still, while the moments specifically about Tomine's comic book career are certainly interesting to read, I think the more universal aspects of Tomine's story are the most fascinating. Like his courtship with his wife, which we get to see develop fairly quickly via a series of vignettes. The most powerful sequence in the book, by far, is one of the longest sequences overall (many of the vignettes in the book are just a couple of pages long, but it feels like the more embarrassing the story is, the more space it gets), where Tomine experience a health scare and finds himself going to the Emergency Room (while trying to avoid scaring his daughters in the process. The problem with doing that, of course, is that if you succeed, then you're inherently leaving them for a scary endeavor while they just want you to stop bothering them while they're watching cartoons). Tomine allows us insight into all of his darkest impulses during those moments, but also a good deal of profound thoughts, as well. It's always so off-kilter, though, as Tomine knows how to deliver an often sentimental story in an offbeat fashion.

This is an excellent graphic novel and it is the sort of work that makes me want to go back to 1982 and shove it in the faces of the "stupid idiots" that Tomine went to elementary school with to show them that young Tomine has achieved his earliest goal in life.