One of the things I tell my students fairly often, both in the writing and drawing classes I teach, is this-- you need to look at real things.

It was something that was beaten into me by my own writing and drawing instructors throughout high school and college until it was practically coded into my DNA.

At the time, it really annoyed me. I knew about real things. I wanted to tell stories about UNREAL things, fantastic things like spaceships and vampires and superheroes. Secret agents who discovered villains plotting world domination from a hidden fortress in a hollow volcano. Men who were chosen to travel through time in order to protect the flow of history from those who would alter it for their own wicked purposes. Stuff like that. Those were the stories I loved and those were the kinds of stories I wanted to make myself. Why would I want to look at real life? Real life was my problem. Making up stories was my escape.

And those are usually the stories my students want to make too. They're all about the magical girls, the hidden mutants with powers, and so on and so on. It's what they like, it's what they want to do.

But here's what I always end up telling them. "Look, stuff like this, magic, other worlds, it's a brutally heavy lift for a writer. You have to really sell it. And the way you sell it is to have people act like real people. That's true of every kind of story but it's especially true for something where you have to put across something hugely UN-real." And then we usually spiral off into why a kid wouldn't confide in his parents when he discovers he can fly, or why in the world someone about to sneak in to a suspected bad guy's headquarters wouldn't carry a cell phone, like for example to call a cop... not to mention figuring out why sneaking in makes more sense than just calling a cop in the first place. You know, the basics. Simple plotting advice. Idiot-proofing.

This is what I'm telling my twelve-year-olds and they get it. So it annoys me beyond reason when actual pro writers apparently don't.

I've talked about verisimilitude as it applies to superheroes before, but an example just came up again a couple of weeks ago, on the new Flash TV show. We got on to it in the car the other night when I was taking Tiffany home after class -- she's my TA in Young Authors and a writer herself, so the commute is usually spent talking about writing tropes of various kinds. (Well, mostly, I rant and Tiffany politely puts up with it.)

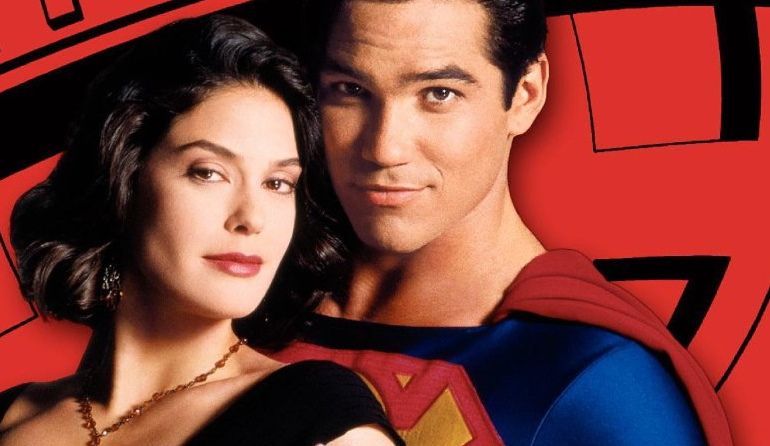

In this particular case, it was the romance genre and how much of it is built on the requirement that the guy or the girl or both can't reveal their true feelings, and how this is the place where writers always screw up. Flash was just my bad example. "Here's the problem with The Flash," I was saying. "It's a great show and for the most part it's really well-done, but the character of Iris makes no sense at all. The way they've set it up she's a mouth-breathing moron, she's completely oblivious to everything around her. Completely. And yet she's supposed to be smart and a go-getter and so on. What's more, Barry allegedly loves her but he lies to her more often than to anyone else, and her dad is even in on the lie too for God's sake. It's the whole Lois Lane problem again but turned up to eleven."

"What's the Lois Lane problem?" Tiffany wanted to know.

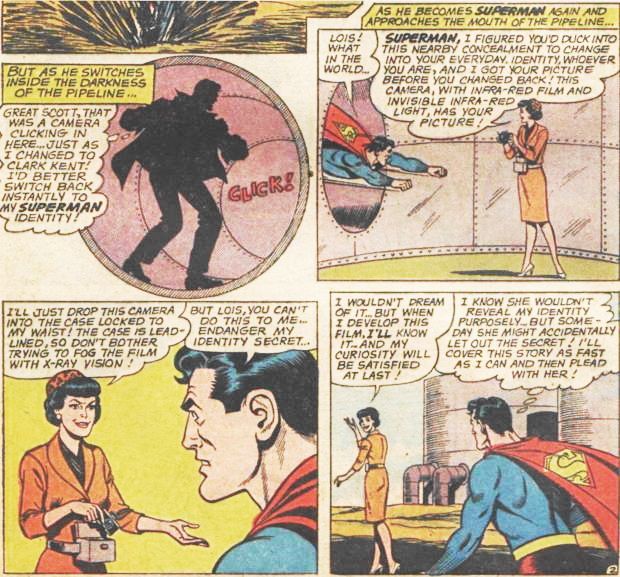

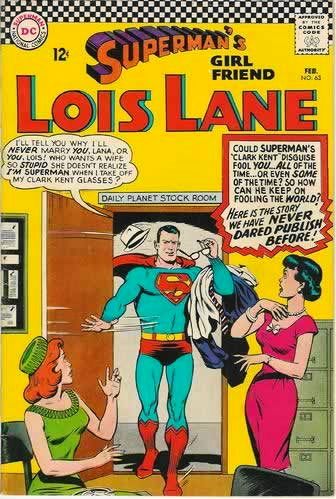

Well, I'd asked for it. I knew what I meant but I'd never really articulated it before. "Um... well, okay. Here's the basic premise of Lois Lane. She's the smartest reporter at the Daily Planet, she's a relentless investigator and an award-winning writer and just an all-around super-journalist. But in the next breath we are supposed to accept that she never figures out the co-worker she sees every day, Clark Kent, is also Superman, the man she loves unrequitedly from afar, even though his only disguise is a pair of glasses. Likewise, we are supposed to believe that Superman is such a giant douchebag that he would never ever confide in this woman he allegedly loves but instead lies to her every single day, maintaining this deception even when, as Clark Kent, he is privy to her most private confidences about how much she loves Superman and how much it pains her that he doesn't notice her. It's supposed to be for her protection but Lois is in danger all the damn time anyway, she'd be in less danger if she knew the truth. It's completely unbelievable. I can believe that a Kryptonian can fly and that bullets bounce off his chest, but I can't believe that Superman, the truth and justice guy, would lie to the woman he loves like that, daily, with so little distress, unless he's really just a prick. Think about it. Keeping a big secret from people you love is hard and it hurts, but Superman stories almost never play it that way."

"Not in the comics, not on TV, not in the movies. It's always about making us feel smug about fooling Lois again, because really, the silly bitch deserves it."

"What's more, it's almost sadistic in the way the situation makes Lois look so idiotic. It's really hard to buy that Lois is as smart as she is when she doesn't figure the secret out on her own, or that Superman would still be in love with her even when she's shitty to him as Clark all the time. The only reason this absurd secret-identity rationale endures is because it zeroes in on the most sacred nerd guy fantasy of all-- if she knew what I was really like, she'd regret being such a bitch and she'd throw herself at my feet. But there's better ways to get there, you don't have to sacrifice common-sense plotting to do it. Or the basic humanity of the people involved. The go-to baseline for most of a century with Lois Lane and Superman when you scrape the paint off is that he's a liar and she's an idiot." I harrumphed. "And now they're doing it again on The Flash. Literally, everybody but Iris that is friends with Barry knows he's the Flash, including Iris's father. Barry's even revealed who he is to villains who've sworn to kill him. But there's this totally artificial dilemma where he can't tell Iris the truth, and it doesn't make any kind of sense either emotionally or from a common-sense standpoint. It irks me."

But Tiffany was still on the main idea. "So how do you solve it? How do you fix the Lois problem, then?"

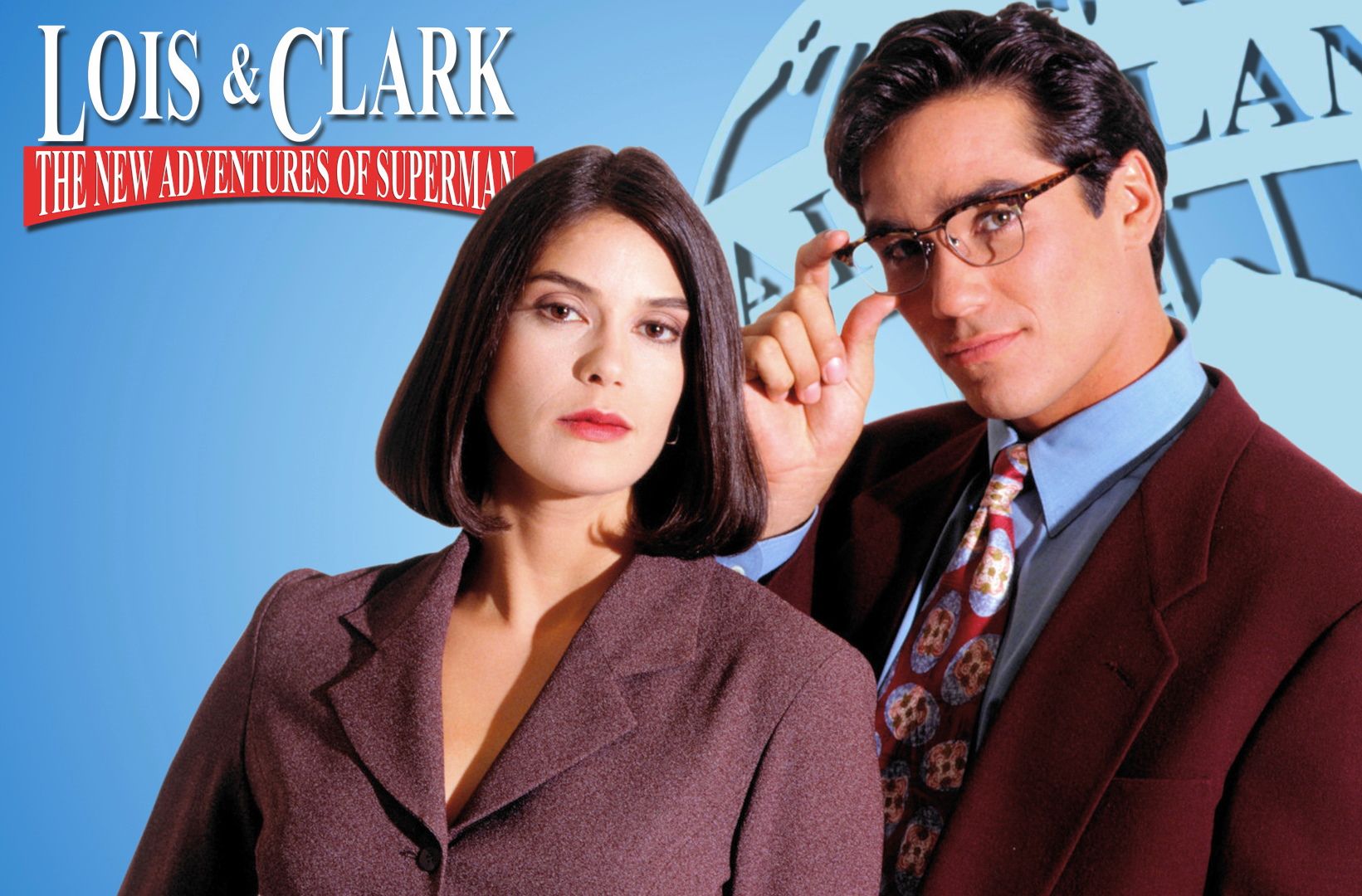

I opened my mouth and what came out shocked me. I'd never considered it before, but the answer was suddenly obvious. "Someone already did. There was a television show about twenty years ago-- you'd really like it, it was called Lois and Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. Basically it was Superman but done as a romantic comedy. And the weird thing is that not only does that idea really work, but it solves the Lois Lane problem."

Tiffany loves romantic comedies, and this really got her attention. So I spent the rest of the ride telling her about how Lois & Clark had stood the traditional romantic triangle on end from all the other versions, beginning by more or less adapting the John Byrne 1980s revamp but adding to it and layering it with classic romance tropes.

And it was such a simple, brilliant idea: you don't start with Kal-El on Krypton who eventually has to adapt to being human, you start with Clark in Kansas learning how to be Superman. I guess you have to credit Byrne for the concept, but it was the TV show that really made that sing. Superman's problem in Lois & Clark is the inverse of the nerd-guy fantasy-- If only Lois knew that my heroic Superman jock self was really sweet-natured nerdy Clark, would she still love me?

Sure, lots of fans hate it. Sure, there were lots of things wrong with it -- the endless Elvis jokes with Perry White, the silly slapstick gags, the smirky cameos from stars who clearly felt they were slumming it, and so on and so on. And it really went off the rails about halfway through the third season.

But they got a lot of stuff right, and I really do think it's the only version to ever solve the Superman-Lois-Clark problem; setting up a situation where you can believe that both Lois and Clark genuinely love each other but Clark is still compelled to lie, and Lois is still oblivious to the obvious. In this version it makes sense for Clark to keep his secret and be tormented by it. It makes sense for Lois to be infatuated with Superman and ignore Clark since she's also infatuated with Luthor for a while; she's drawn to men who are powerful and trying to make a difference. Suddenly all the secret-identity stuff made sense. Clark had this huge conflict where he feels crappy about lying to the woman he loves and is trying to figure out how to resolve it. At the same time Lois is slowly coming to the realization that it's CLARK, not Superman, that she cares about... and this realization is freaking her out so she is compelled to deny it. Meanwhile Lex Luthor is suddenly very hampered in his operations by the realization that he's genuinely fallen for Lois as well: he doesn't want to own her or use her, he loves her, and that is seriously messing with his head. The engine that drove the thing was really well-conceived and writers could (and did) ring all sorts of changes on those basic ideas.

In TV, of course, you can only string it along so long, and Dean Cain was right when he said in interviews they HAD to pay it off eventually or fans would have rioted. When I say the show went off the rails, though, it was never about the romance getting consummated or Lois eventually learning the secret and marrying Clark. In fact, the episode with the reveal, "We have A Lot To Talk About," that opens the third season is one of my favorites-- mostly because of this clip and this one.

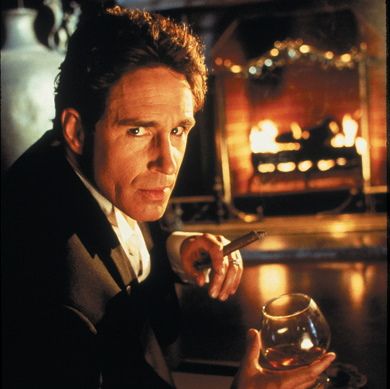

No, the trouble was that they forgot the fact that Lois & Clark was also still an adventure show, they got too invested in the comedy part. It was that the stories, and villains, started getting sillier and sillier. But when they had genuinely nasty, motivated villains-- Trask from Bureau 39, John Shea's Luthor, even Tempus-- that were committing seriously evil crimes that jeopardized not just Metropolis but also Clark's private life, that show really cooked.

Serious but not TOO serious, funny but not TOO funny-- that's a hard line to walk and lots of adventure shows blow it. I'm not surprised Lois & Clark often did. But when they were on, they were really on. I ended up watching most of the first two seasons again over the last couple of days and, you know, it holds up pretty well. Certainly Teri Hatcher's Lois-- and her original crew of writers, especially John MacNamara, Bryce Zabel and Dan Levine-- could teach Candace Patton's Iris and her writers a thing or two about applying real-people characterizations to a superhero story.

Because when you don't, you're left with congenital liars and stupid people, more often than not. Lois and Clark, and Barry and Iris, deserve better.

See you next week.