A Centaur’s Life, Vol. 1 (Seven Seas): Easily the weirdest comic I read this month, Kei Murayama’s manga is about an alternate world where everything is the exact same as it is in ours, save for the fact that there are multiple races like centaurs, angel folk, goat folk, cat folk, dragon people and so on. Oh, and while human beings apparently still exist, the only one glimpsed is a medieval knight seen in flashback, having enslaved a centaur is some bizarre armor/restraining device in order to ride him.

What makes the manga so weird, however, is that there doesn’t seem to be any reason, at least not in this first volume, for why our heroine Himeno is a centaur, and why her classmates are all various fantasy races living out an otherwise completely mundane existence.

Himeno is a sweet, shy, pretty and popular Japanese schoolgirl (who is also a centaur). She’s afraid of boys, likes hanging out with her friends, and love sweets, although she worries about getting fat. The stories are mostly of the frivolous high-school comedy sort that could easily have been told with human characters.

In the first story, Himeno is self-conscious about her genitals, which she’s never looked at, as she’s afraid they might resemble those of a cow the kids once saw on a field trip (unlike some centaurs, the ones in this comic keep their horse parts covered in elaborate pants that appear difficult to put on and take off). In another, her class puts on a play, and she’s cast as the female lead, while her best friend -- a girl with bat wings, a spade-shaped tail and pointy ears -- is the male lead. In another, she’s suspected of doing some modeling work, in violation of school policy regarding part-time jobs.

There’s nothing terribly centaur-y about any of it, and if Murayama is building to anything in future volumes, it’s not evident yet. Not that there’s anything wrong with an artist just drawing centaurs and school kids with horns, tails and animal ears just because that’s what the artist wants to draw, of course. I was just expecting some supporting rationale for the fantastical surface elements.

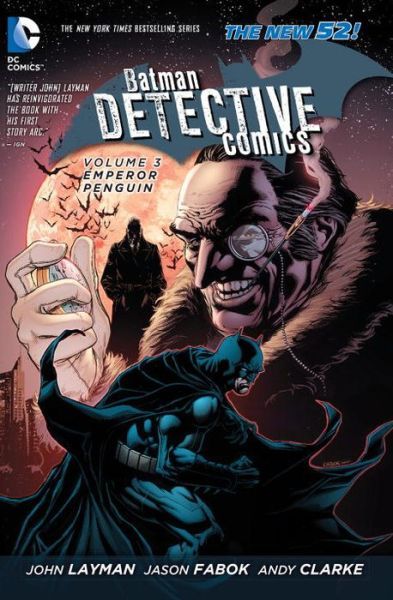

Detective Comics ,Vol. 3: Emperor Penguin (DC Comics): This hardcover collects the beginning of writer John Layman’s run on the title, for which he’s paired with artist Jason Fabok on the feature stories and Andy Clarke on the back-ups.

The storytelling is understandably a bit messy because the issues it collects are split into features and back-ups, and they tend to read rather awkwardly in trade, flip-flopping artists and changing focus and point of view (I’m not sure what the best way is to collect these comics with back-ups; the Action Comics model, in which all of Grant Morrison’s feature stories proceed all of Sholly Fisch’s back-ups, doesn’t read quite satisfactorily either). Additionally, the “Death of the Family” arc intrudes, somewhat derailing the proceedings, although Layman does put some effort into integrating it into the story he’s trying to tell on either side of it.

That’s the story of Oswald Cobblepot’ s right-flipper man Ignatius Ogilvy usurping his boss’ criminal empire, grabbing a monocle and a trick umbrella and declaring himself “Emperor Penguin.”

It’s nice to see a fresh face of villainy in a Batman comic, even a “spinoff” version of an existing character, particularly given how many of the standards Layman lines up in these issues. In addition to The Penguin and The Joker (for a few panels), Poison Ivy, Clayface and Mr. Zsasz figure rather prominently, the latter’s origin now tweaked so that it was The Penguin’s casino in which he lost all his money and turned to serial-killing.

The “Death of the Family” tie-in is one of the least essential, and while it’s not a bad story on its own, it warps the proceedings around it, pushing the storyline that gives the collection its subtitle into the fringes for a while.

Judging from what's collected herein, TEC seems to be, or at least to have been, the most average, median-quality of the Batman books -- not the best of them, but certainly not the worst, either.

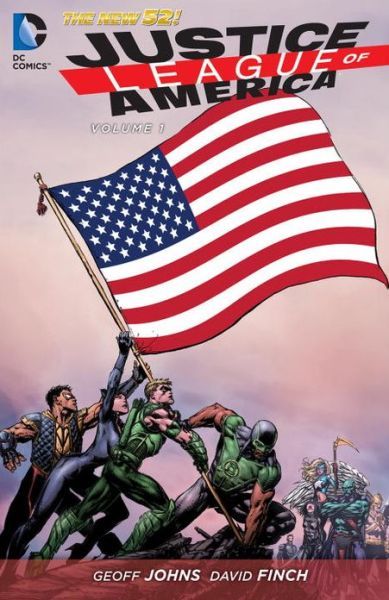

Justice League of America, Vol. 1: World’s Most Dangerous (DC): While reading through this collection of the first seven issues of Justice League of America, I found myself regretting every time I complained about someone writing for the trade. While it can be irritating to pick up a monthly comic book containing a story with no real beginning, middle or end and knowing you’re being charged to read one-sixth of a writer’s graphic novel, here I discovered maybe the exact opposite problem. This is a collection of comics most definitely not written for the trade, comics written so specifically to be read in single issues that their ultimate collection seems almost random, like comic book gobbledygook.

Inside we find three major sections. First, there’s five-part title story, written by Geoff Johns and mostly drawn by David Finch (who, despite being announced as the artist of the series, only managed three issues before moving on to Forever Evil) and finished up by Brett Booth. That’s the story in which A.R.G.U.S.’s Amanda Waller and Steve Trevor put together the unlikely superhero team of Martian Manhunter, Hawkman, Green Arrow, Catwoman, Katana, Green Lantern Simon Baz, Stargirl and Vibe to take down the real Justice League. But first they end up investigating and fighting the Secret Society of Super-Villains and its members, like Copperhead, Signal Man, Blockbuster, Professor Ivo and his Shaggy Man, and The Outsider.

Then we get Johns’ “Trinity War,” but only the three chapters of the nine-part series that took place within this title, all drawn by Doug Mahnke. While “World’s Most Dangerous” leads rather directly into “Trinity War,” reading every third chapter of it back-to-back-to-back certainly isn’t the best way to read it, with every chapter following a cliffhanger from another chapter, not included in this book, and each chapter ending with a cliffhanger that’s not resolved within these pages.

Finally, there are more than 30 pages of Martian Manhunter stories that take place in and around the chapters of “World’s Most Wanted.” These are written by Matt Kindt and drawn by four different art teams, telling the New 52 version of J’onn J’onnz’s origin — the changes to which simply seem to be changes for change's sake, rather than improvements or moves to simplify an already quite streamlined character — while filling in some blanks from the title story arc.

Whatever virtues these comics might have, this doesn’t seem to be the way to experience them, as JLoA, whatever else one might say about it, is written for the monthly, serially published comic, not the trade.

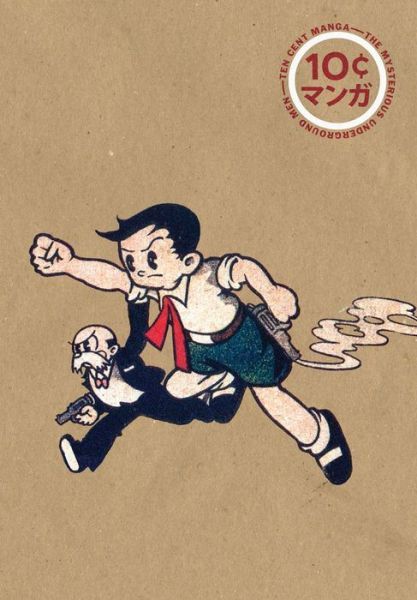

The Mysetrious Underground Men (PictureBox): The latest entry into editor/translator Ryan Holmberg’s Ten-Cent Manga series, devoted to presenting early Japanese comics that reflect Western influences, is an early work from a manga-ka who needs no introduction: Osamu Tezuka.

Loosely based on 1913 German novel Der Tunnel (which I’ve never read, but I’m fairly willing to bet it didn't feature a rabbit turned into a Disney-style anthropomorphic bunny through various machines and painful processes), it breathlessly, even frantically, tells the story of young go-getter John, who makes a death-bed promise to his father to invent a safer way to travel than airplane.

What John comes up with is a “trans-Earth” rocket-train that can travel through one end of the world to the other, once a tunnel is drilled all the way through the globe. John and his allies, including the anthropomorphic rabbit Mimio and his Uncle John, bore the hole, but along the way they discover a hostile race of termite people, who are determined to conquer the surface world, with the help of a turncoat among John’s party.

The events mostly echo those of old film serials, but what makes them perhaps more extraordinary here is the speed of Tezuka’s narrative with its ever-escalating stakes, Tezuka’s already rather accomplished cartooning skills (which transform the standard sci-fi serial fare into something unique looking), and the tragic story arc of rabbit-turned-rabbit-shaped human Mimio’s attempts to prove himself to his friends, no matter what the cost.

The generous amount of supplementary material, about 40 pages of essays, makes Mysterious Underground Men seem all the more remarkable, as Holmberg reveals the many and varied sources of inspiration that the young Tezuka absorbed and synthesized into a new narrative that seemed upon original reading a thing all of its own: Der Tunnel, Disney shorts, Blondie comic strips, Milt Gross’ He Done Her Wrong, Popeye, Flash Gordon and more.

One important function Holmberg’s series performs, beyond bringing great comics to our attention, (the function I’m personally most interested in), is the way in which they emphasize the porous nature of comics culture, and that influence and inspiration isn’t something that can be charted east to west, west to east, right to left or right to left. It seems much more turbulent than that, with comics, culture and, of course, pop culture in the early 20th century a sort of solid, celluloid and paper manifestation of a collective unconsciousness. I suspect that will seem more and more evident the more volumes of Ten Cent Manga come our way (I wrote a few weeks ago, prior to learning about PictureBox's rapidly impending dissolution. I'm hopeful that Holmberg's Ten Cent Manga series will find a home at a new publisher, just as I hope all of the many great cartoonist whose work PictureBox published and championed will find new homes).

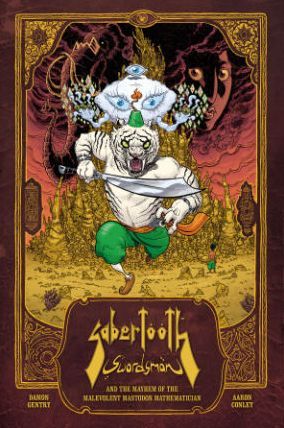

Sabertooth Swordsman and the Mayhem of the Malevolent Mastodon Mathematician (Dark Horse): If the title doesn’t do it all on its own, the cover image oughta: This comic is exactly what it sounds like, the story of a sword-wielding sabertooth tiger. What isn’t as evident is the wild, somewhat silly tone of the fairly straightforward sword-and-sorcery action adventure, which features highly intricate, world-building artwork evocative of James Stokoe (Orc Stain, Wonton Soup), the only semi-serious sci-fi scripting of Brandon Graham (King City, Multiple Warheads and, to a lesser extent, Prophet), and even some of the arcade logic seen in works like those of Corey S. Lewis (particularly Sharknife).

If you like any of those artists, and any of those works, and I have to assume you do, as they are some of the best and most exciting to have been publishing work regularly in the past few years, then chances are you’ll also like writer Damon Gentry and artist Aaron Conley's Sabertooth Swordsman, which feels a lot like that work, without seeming the least bit derivative.

Conley's highly, almost baroquely detailed artwork is nevertheless quite cartoony, the fluid action and figure work collaborating with a reader’s eyes in animating the pages, and the expressions of the lead character and, most especially, his patron god, evoking high-end magazine illustration.

In other words, this is a great-looking comic, and you’d be hard-pressed to find better cartooning between any pair of covers published recently.

As for the story, it seems equally influenced by The Hero With a Thousand Faces and old side-scrolling video games, consisting of little more than spectacular, imaginative fight scenes, with occasional breaks for comedy (Sabertooth Swordsman is rarely greeted as a hero, despite having his name on the cover) and melodrama (with his kidnapped wife, the inspiration for his quest).

So when a poor, be-fezed farmer loses his wife to the forces of the Mastodon Mathematician, he sets out to climb Sasquatch Mountain, where he is transformed by the cloud god into an anthropomorphic tiger man, with long, sabertooth-like fangs and a scimitar (oh, and the tassel on his fez is now an eternally burning flame — cool!).

Thus empowered, and having proved himself in combat by besting the giant beast that gives Sasquatch Mountain its name, he sets out to rescue his wife. He samples hallucinogenic bug-meat and trips balls, gets in a bar fight, encounters a crazy cat lady, battles a herd of giant goats (and, after slaying them all, their goat ghosts!), squares off against a couple of cycloptic professional wrestlers and more than one giant monster.

The “and…” in the title promises, or at least holds out the possibility, of future adventures. It’s difficult to imagine where they might go from here, as all this book has to offer is incredible artwork, insane character designs, amazing action sequences and plenty of jokes…wait, that’s actually an awful lot of well worthwhile stuff to offer. Never mind.