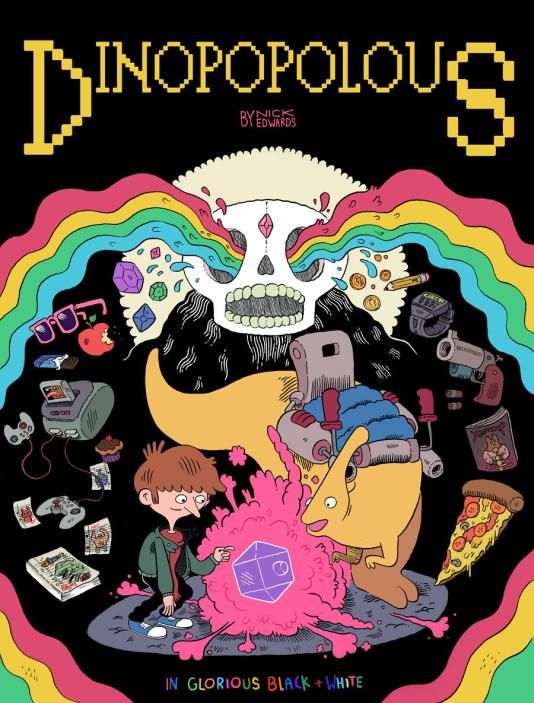

Dinopopolous (Blank Slate) Nick Edwards' Dinopopolous is the story of Nigel, a 13-year-old who loves comics, videogames and heavy metal and who solves mysteries with is best friend Brian, who is a talking dinosaur.

You have probably already decided that this is a comic book you would like to read, and I concur with your decision: This is a comic you will like reading.

When an archaeologist on the trail of the Miracle Bird of Ndundoo goes missing, Nigel and Brian are given a pre-pre-pre-historic artifact and tasked with finding the bird before Julian and His Evil League of Lizards, humanoid lizards that dress a little like the saiyans from Dragon Ball Z, and reminded me of the Tyrannos from DinoSaucers. And Brian reminded me a bit of a mount from the old Dino Riders toy line, wearing a saddle with guns mounted on it and all. And, tonally and visually, the entire book reminds me a bit of Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time, all of which are farily positive associations in my mind.

The story itself is extremely straightforward. Our heroes find the trail, follow it, come into conflict with Julian and his League and then find the bird on the 25th and penultimate page of the book, which ends with a splash page reading “The End” in the middle of an explosion, while Nigel throws up some devil’s horns.

The cartooning, however, is amazingly complex. Each panel, big or small, is crammed with details, and Edwards offers a few remarkable sit-and-stare sequences.

One is a two page spread in which he draws a twisty underground tunnel across a two-page spread, with multimple images of our heroes posed at different points along the tunnel in implied panels, having various mini-adventures.

In another, they touch an ancient, mystical artifact and transcend “body and mind in order to overcome material obstacles,” which leads to a bravura two-page sequence in which Nigel makes his way through a trippy, rigorously-cartooned doodlescape that defies accurate verbal description.

It’s a slim book, but it’s not a slight one.

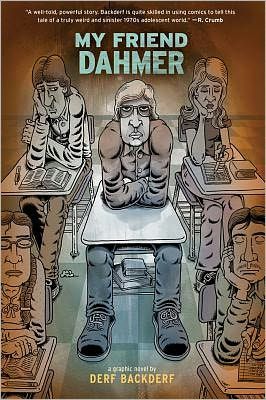

My Friend Dahmer (Abrams ComicsArts) I’m willing to bet the story of this book’s gestation and creation is every bit as interesting as the story between its covers, albeit less marketable.

John Backderf is a long-time alternative cartoonist maybe best known for his strip The City—if you’ve read many free weeklies in many big cities, chances are you’ve seen his work—who has more recently branched out into graphic novels like Trashed and Punk Rock and Trailer Parks.

He also happened to go to high school with a kid named Jeffrey Dahmer.

I don’t want to assign Derf emotions or anything, but I got the feeling that this was a very difficult project, something he felt like he had to do—or had to not not do—despite the enormous risks and difficulties that come with any work that does anything to humanize someone who has been so universally condemned as an inhuman monster (I get that feeling because even as I wrote that previous sentence, I felt like I needed to follow it with a parenthetical qualifier like, “And of course, Jeffrey Dahmer was a monster.”). That, and I imagine Derf worries about doing anything that might be seen as exploitive, or attempting to profit off the real tragedies of the Dahmer’s victims.

I suppose the provocative title only heightens some of those problems, but I can’t think of a better title. That is the story being told: The story of this weird, obviously troubled kid that the author knew in high school, that he and his real friends hung around with as sort of a mascot for a while and who ultimately grew up to become one of America’s worst and most notorious serial killers. It’s the story of how shocking that turned out to be…and how maybe it was not really that shocking at all, in retrospect.

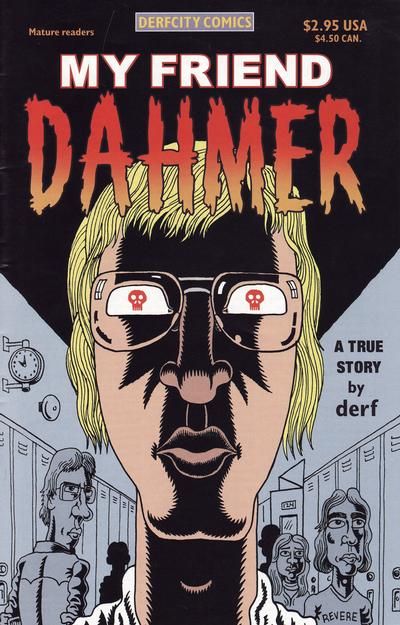

It’s worth noting that Derf refers to this as a 20-year work-in-progress in his introduction, and the graphic novel was prefigured by a shorter attempt with a self-published, comic book-sized version of the story in 2002. There too Derf stresses that he while Dahmer can be pitied, he shouldn’t be empathized with, and while the society around him in his formative years can be blamed—“It’s my belief that Dahmer didn’t have to wind up a monster”—once Dahmer chose to kill and keep killing, he became solely responsible for his crimes.

In that same prose piece, Derf refers to this as the best drawing of his career, and as someone who has followed that career fairly closely (I live in the same state as Derf, and am always particularly drawn to the work of local creators), I agree.

His figure work and caricature-like cartooning is highly refined, but it’s altcomix roots are always evident in the long limbs, big hands and feet, and highly detailed, almost grotesquely over-featured faces. And while I hate to use a charged term like cinematic when discussing comics, Derf makes use of the space the extended format provides, delivering powerful sequences of images that guide the reader visually and aurally through portentous moments.

After one such outstanding equence, in which we meet a very young Dahmer walking down the road in his rural, small town Ohio neighborhood and discovering the corpse of a cat, Derf begins his story in seventh grade, and follows Dahmer through shortly after their graduation from high school, and shortly after Dahmer’s first murder.

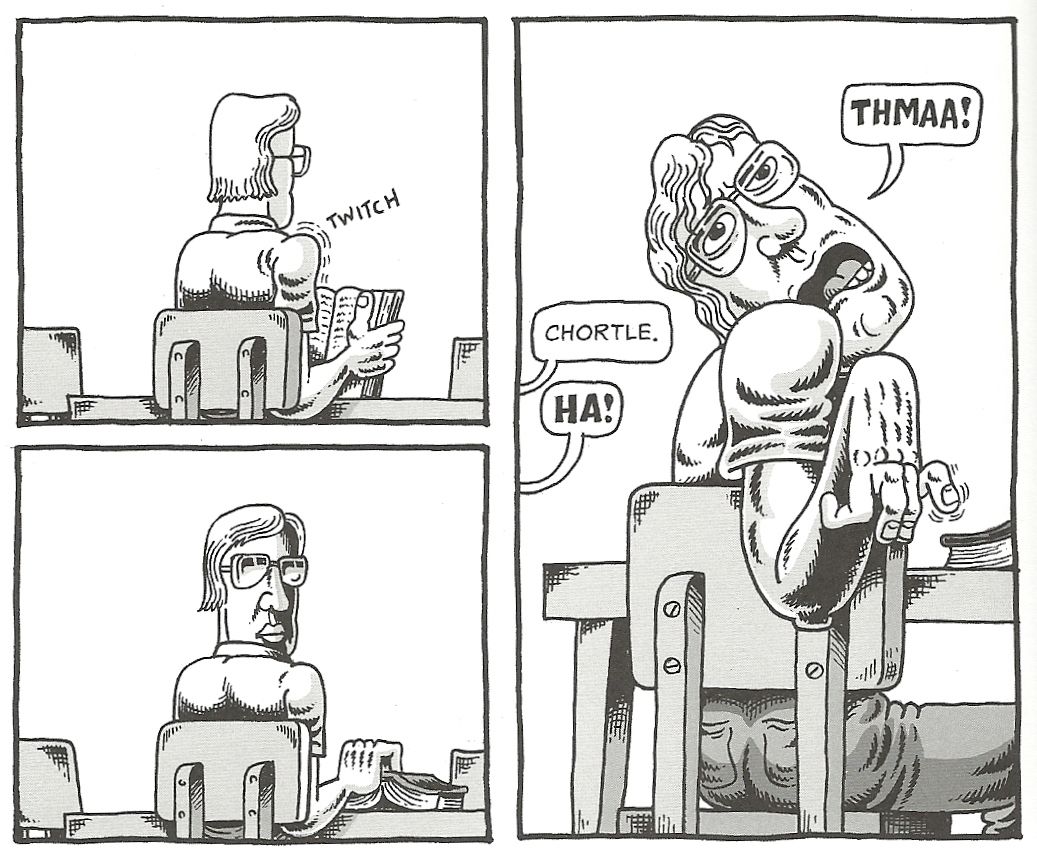

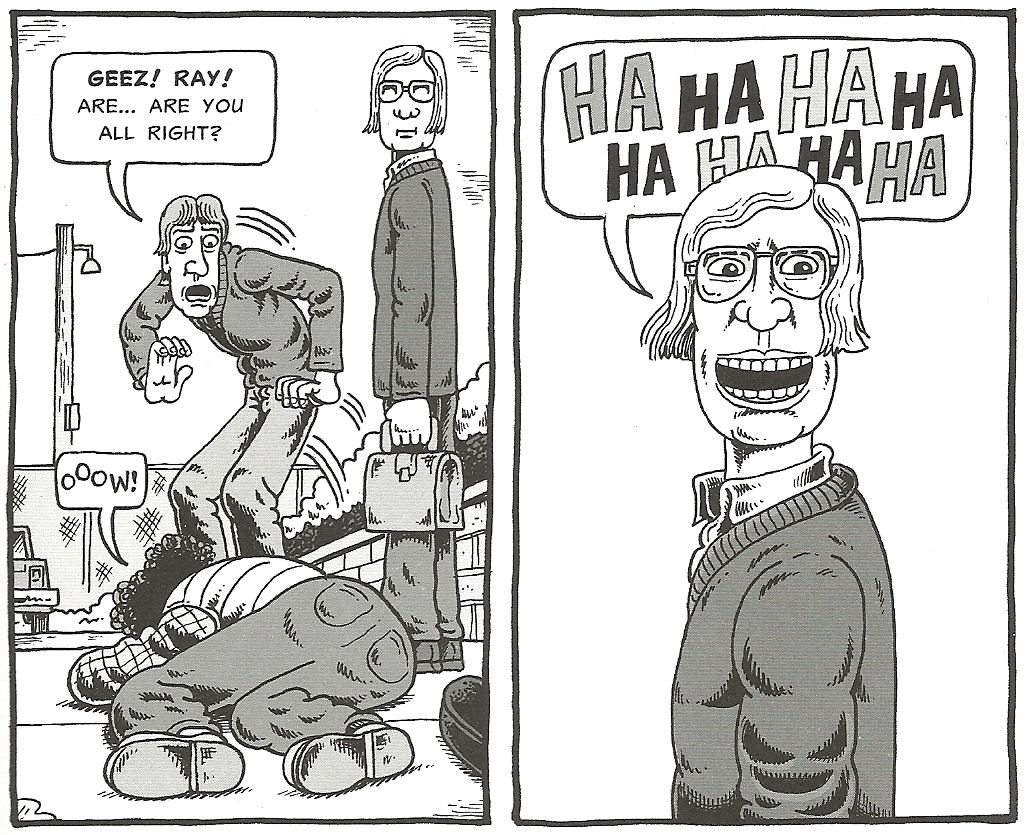

It’s a furiously compelling read, one that once begun is hard to turn away from. Derf’s Dahmer is pitiable, particularly when we first meet him being bullied in seventh grade, and then learn of his significant family problems. He’s also lonely and strange, his main interaction with his classmates coming from his impersonations of someone with cerebal palsy, which cracks up Derf and his friends.

Derf's Dahmer reveals only flashes of being somehow broken, or sinister (laughing inappropriately when someone gets hurt, for example, or chopping up a still-living fish just because he wants to see what it looks like).

What Dahmer does reveal is that he’s obviously very troubled, particularly by the time they all reach high school and he is drinking all day every day, a fact that seems downright bizarre today, but the seventies were apparently a very different time.

Derf often draws Dahmer with his glasses opaque, hiding his eyes completely. More tellingly, when we do see through the glasses at Dahmer’s eyes, they look as and emotionless as the lenses of his glasses.

While Derf occasionally illustrates what he himself wasn’t there to see, having much more thoroughly investigated the case, circumstances and his former classmate’s life between the time he selfpublished the comic book and now, he stays outside of Dahmer’s head, depicting his actions without depicting the man's thoughts.

It can be a tough read, mainly because there seem to be so many opportunities to catch Dahmer during his slide towards monsterhood, the closest brush coming when police stop him while he has garbage bags full of a victim in the back of his car, but obviously no one ever did. One knows the ending of the story, and while My Friend Dahmer shows the beginning, its most thrilling, horrifying aspect is its progression, seeing what reality tells us will inevitably happen unfold, and knowing it wasn’t inevitable at the time, but that time has passed.

I hope the work, as difficult as it is—I’ve personally seen people recoil when I’ve mentioned it to them before based on the title alone—gets the attention it deserves this time around. It’s a major work from a major talent, and, I think, an important work, both for its formal achievements and as its reminder that whether monsters are born or made, they all grow.

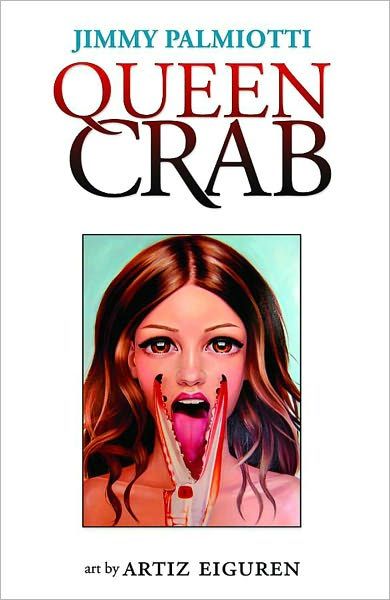

Queen Crab (Image Comics) Even the most established of comics pros are using Kickstarter these days, apparently.

Jimmy Palmiotti, longtime comics inker, co-founder of the Marvel Knights imprint and current writer of All-Star Western for DC Comics, crowdfunded this project through the popular website.

Queen Crab is a somewhat interesting departure for the writer, still well within the realm of superheroes—perhaps a little too much so, given the lack of closure that seems to be leaning toward a sequel of some sort—but in the more atypical regions of the genre.

The title character is Ginger, a rather unlikeable young woman who uses the words “retard” and “dyke” rather freely and, when we meet her, is about to break off her relationship with her lover, as she’s going to marry her fiancée. (She also has sex with her female boss in order to keep her not-very-good job, but that’s rather here nor there, and a weird, tacked-on scene).

On her honeymoon cruise, something terrible happens to her and she finds herself thrown into the ocean, where she’s transformed: Her arms are now those of a crab, ending in huge pincers.

Palmiotti’s script seems like it could use another draft or two, as the 48-page story is oddly paced, with some 500 or so word of narration in the first panel, and the beginning and ending of the story consisting mostly of establishing via narration an old status quo and a new status quo, with only a stretch in the middle containing much drama or development.

That middle is fairly interesting, though, thanks to the bizarre transformation of our heroine’s limbs, peculiar images like those of her delicately gripping a cigarette in one massive claw, and Palmiotti certainly spices up the proceedings with plenty of sex and nudity. Late in the game he also gives “Queen Crab,” named by a Coney Island freak show manager who wants to recruit her, a handful of aquatic superpowers, but it’s in another rather tacked-on scene, and one that feels out of place…unless there’s a second volume on the horizon, I suppose.

The artwork is by Artiz Eiguren, and it's fine work, if the coloring occasionally makes the lines read a bit blurry, the figures growing muddy in medium or long shots. His is a very representational style, though, and it helps sell the random horror of the transformation.

There’s also a half-dozen pin-ups at the back of the book, from Palmiotti himself, his project editor Amanda Conner and others that offer different looks at the character in very different styles.

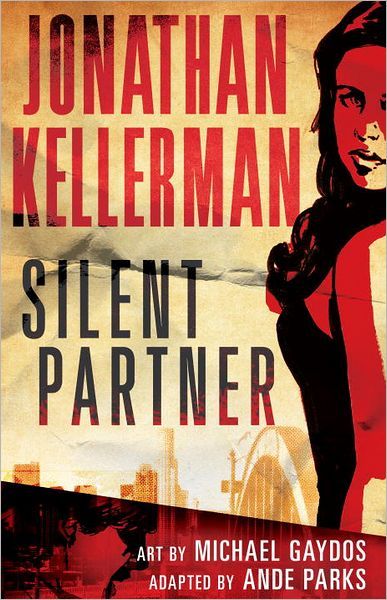

Silent Partner: The Graphic Novel (Random House) This is the comics equivalent of one of those very early Hollywood films, where the language and possibilities of cinema were still being learned, and the result was basically just a play captured on film.

The difference here being that this tedious overly-faithful adaptation of Jonathan Kellerman’s 1989 novel of the same name doesn’t have the excuse of comics being a new and emerging medium; the term “graphic novel” has been around since the 60s or so, and the form longer. And people have been adapting prose into comics for…well, as long as comics have existed really.

In other words, there’s no reason for this to be as terrible as it is.

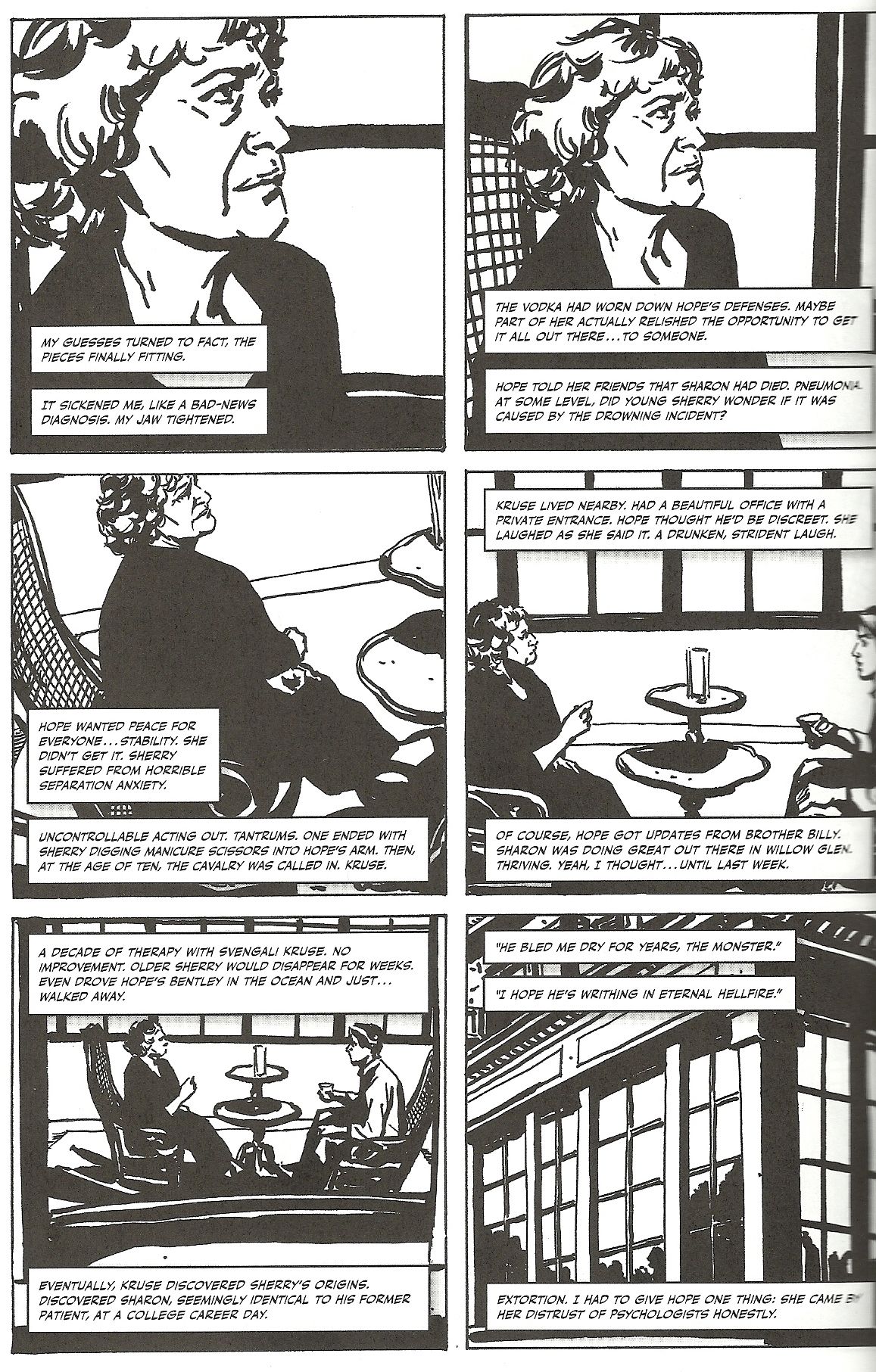

Large chunks of prose, first-person narration are taken from the novel original, dropped into white narration boxes, and then these are divided up into a grid of often extremely static images (a drawing of a building, of a photograph, etc).

It looks like a comic, albeit a very wordy one, but it reads like a novel disguised as a comic book. It’s too bad Faith Erin Hicks hadn’t written her piece on adapting prose into comics a year or so ago, in time for the makers of this book to get a look at it before going to work.

The cover has a big, huge “Jonathan Kellerman” on it, letting one know what the publisher thinks is the selling point, with the names of the people who made the comic small like fine print. Michael Gaydos gets top billing with “Art By,” Ande Parks gets “Adapted By.”

Both are familiar names to anyone who has read comics for very long, so they should know what they’re doing, and should know how to make a better comic than this, but perhaps the material doesn’t lend itself to the form, or at least the strategy chosen to adapt it—keeping the narrator and his voice and doing most of the storytelling through it—doesn’t allow for the form to offer anything new that couldn't have already been told just the same in the original prose novel.

The story features Kellerman’s recurring Alex Delaware character, a child psychologist and police consultant based in LA. The Internet tells me Delaware has starred in 27 novels, and that Silent Partner was the fourth of these.

The story, still set in the '80s, is about Delaware running into a highly troubled old colleague and ex-lover who asks him for help and then gets promptly murdered a few day. Delaware investigates the strange case, which involves an eccentric millionaire, high-class porn collectors/afficiandos, other psychologists and an honest-to-God set of identical twins (with a silly twist I’m struggling to keep to myself, just in case I can’t dissuade you all from reading it).

Gaydos’ photorealistic art serves the story well, even presented in the book’s stark, black and white—no grays or shading—that doesn’t do his work any favors. He’s given nothing interesting to draw. People talking, people talking, people talking, a murder scene with narration boxes all over it, more people talking, a boring narrated sex scene and more talking.

It’s a frankly rather ugly, sterile and dull work that will likely send even Kellerman’s fans scampering back to his prose and their own imaginations of what Delaware and the other characters and their world must look like. Their imaginations can’t possibly be as uninteresting as this comic is.

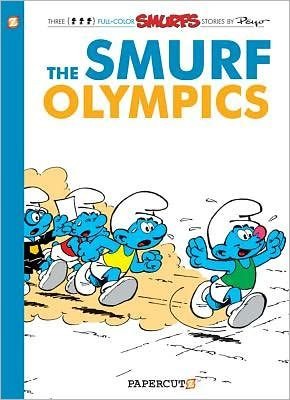

The Smurf Olympics (Papercutz) The eleventh volume of Papercutz’s Smurfs reprint program offers another demonstration of an endearing trait of the little blue socialists: The insane lengths they will go to, many of them somewhat reluctantly, in order to help one of their members feel fulfilled.

In The Astro Smurf, the entire village went along with an elaborate, days-long hoax in order to help trick the one Smurf who wanted to visit another planet into thinking he had met his goal. Here, the entire village put aside their aversion to sport in order to stage an Olympics-like games just because Hefty, their one member who likes sports, is feeling sad that he never has anyone to compete against.

That provides plenty of opportunity for lighthearted jokes about various track and field events, competition, braining Brainy Smurf with sports equipment, and an important message about believing in yourself, even if you seem destined to fail, like the unfortunately named Weakling Smurf.

That accounts for the first half of the book. The second is filled with gag strips—some a page long, some only three panels long—with sports-related content, mostly concerning archery.