I thought it would be an interesting look into our nation's political cartoon history if, this month, I took a look at a different editorial cartoon each day that won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning. Do note that we're talking basically 1922-1967 here, as since then, the Committee has almost always awarded cartoonists generally for their work, not for an exemplary single cartoon. So in many ways, this is a snapshot of American politics (for better or for worse) over a forty-five year period. Here is an archive of the cartoons featured thus far.

Today we look at Fred L. Packer's 1952 award-winning cartoon.

Enjoy!

Fred L. Packer (1886-1956) was one of the earliest prominent editorial cartoonists in California. After an early career in advertising (he designed some absolutely beautiful ads), Packer became a full-time political cartoonist, working first at the Los Angeles Register.

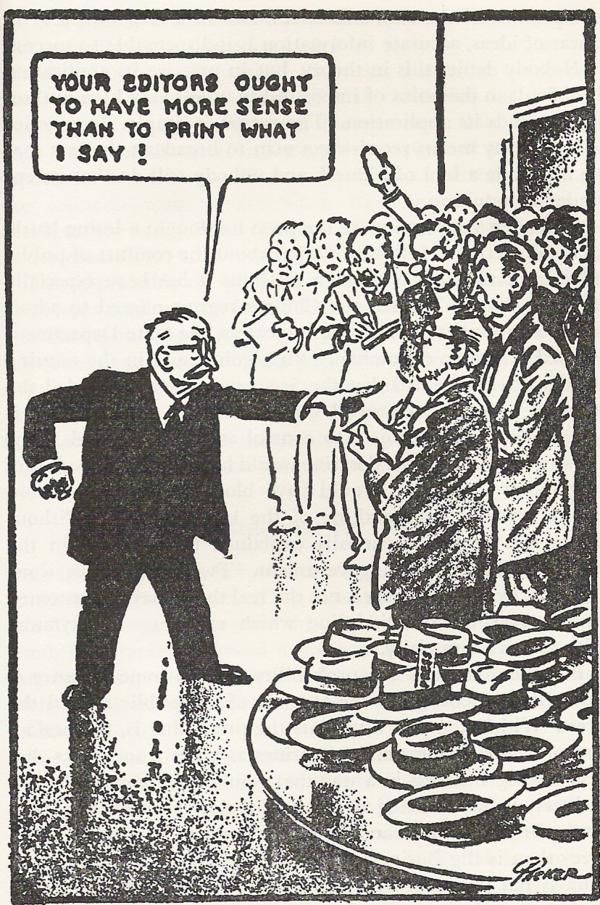

A frequent critic of President Harry S. Truman, Packer won the Pulitzer Prize in 1952 for this cartoon mocking Truman's take on confidential information, titled "Your Editors Ought to Have More Sense Than to Print What I Say!"

Truman generally had issues with matters of privacy, in that he always had a bit of a contentious relationship with the press. However, the particular reference in this cartoon is to an October 1951 press conference by the President where he debuted a new Executive Order (Franklin Roosevelt and Truman were the first Presidents to take full advantage of the power of the "Executive Order" that the President had - there were seven Executive Orders in the first 160 years of the United States, Truman had more than that in just his two terms).

The Executive Order was designed to protect American "classified information." The problem was that the information that set Truman off was information that had been made publicly available to reporters.

It did not help that in his press conference on the topic, Truman deviated substantially from the handout he had given to the reporters at the conference, creating, in effect, two official positions from the President (the written version and the oral version), and the deviation came mostly in the form of the President berating reporters.

The next day, the confusion was cleared a bit when the White House press secretary elaborated on what exactly was Truman's point:

The President has directed me to clarify his views on security information as follows:

1. Every citizen-including officials and publishers-has a duty to protect our country.

2. Citizens who receive military information for publication from responsible officials qualified to judge the relationship of such information to the national security may rightfully assume that it is safe to publish the information.

3. [Citizens who receive this sort of information from improperly qualified sources should be most guarded in passing it along.]

4. The recent executive order does not alter the right of any citizen to publish anything.

So yeah, basically, "Your Editors Ought to Have More Sense Than to Print What I Say!"

In an interview after he left office, Truman had another somewhat embarrassing situation when he called a reporter a liar for saying he said certain things. The report he called a lie was a Pulitzer Prize winning interview from the early 1950s that had clearly been cleared by the President at the time (Truman ultimately apologized for his remarks).