Today's absolutely massive, biggest-ever Reason is written by Ian Astheimer. He leaves no stone unturned, no comic unopened!

He used to be a fry cook at a strip club. Now, he writes some of the best comics on the market.

11/18/07

322. Joe Casey

Next year marks Casey's tenth anniversary as a comics writer. Frankly, it feels like he's been at this game a lot longer. Maybe because he's written virtually every character under the sun.

Casey credits James Robinson for kick-starting his career. In 1998, Casey took the reins of Cable from Robinson, mid-way through a six-part arc. Although those initial issues featured standard fisticuffs (Cable vs. Master Man! Cable vs. the Hellfire Club!), it wasn't long before Casey put his stamp on the character, focusing on the humanization of Nathan Dayspring Summers. Cable's days as a mercenary for hire were behind him. His huge guns and huger pads were gone. Now, he was something of a vagabond, searching for Apocalypse while struggling with the techno-organic virus that threatened to run rampant. He lost his telepathy and gained the psimitar -- which harnessed the totality of his telekinetic powers -- from a group of monks who worshiped him. He disbanded them. Cable also befriended Stacey Kramer, a kindly waitress at a diner. It was a much-needed human connection, an emotionally honest oasis away from hue-shifting reporters and time-traveling aliens. Nathan promised to reveal everything to Stacey, to come clean about his past, to finally achieve catharsis. But, I'm not sure he ever did. Being hunted by SHIELD can put a damper in any plans, so can shifting creative teams.

When Jose Ladrönn, Casey's collaborator on the series, was asked to leave the title, Casey agreed to go with him. The duo was replaced by Joe Pruett and Rob Liefield, just in time for The Twelve crossover, which finally saw Cable fight -- and eventually defeat -- Apocalypse.

From there, Casey segued immediately into Deathlok, with Leonardo Manco, for the Marvel's M-Tech line. The series was actually a spin-off from his Cable run, featuring Jack Truman, Agent 18, who had been tasked with apprehending Nathan Summers for SHIELD. Truman, badly burned by a ruptured turbine, was handed over to a nefarious organization he was investigating, ExTechOp, which subsequently experimented on him, turning him into a cyborg. Stripped of his senses, save sight, the agent attempted to bounce his psyche into a SHIELD employee. He missed. His mind landed inside the employee's son, a six-year-old named Billy. Cue existential crisis. Truman's body -- sans a mind -- tore through Vegas, until Billy arrived and Truman jumped back into his old form.

Joining SHIELD once again, the new Deathlok was instrumental in ending the Ringmaster's bid for presidency. Truman eventually regained his humanity -- by swapping minds with a dishonorably discharged SHIELD agent.

Buddhist mind-swapping wasn't the only trick up Casey's scripting sleeve, however. The series also used caption boxes to great effect; during the heat of battle, the mindless cyborg body, attempting to learn or at least process his surroundings, would define the words that were shouted at him. It was a clever way not only to show the cybernetic man's otherness, but also to educate kids who might be reading. Plus, it reinforced the reflective dichotomy of the central character; while Truman's psyche was trapped in a child's body, Truman's body was rendered childlike without his mind to guide it.

Casey also tackled the thankless task of following PAD on The Incredible Hulk, with Javier Pulido and Ed McGuinness handling the art chores. You'd be hard-pressed to find a character who's more indicative of the struggles of humanity, of not losing control, of not lashing out.

During Casey's brief run, the Hulk faced off against the Circus of Crime, who were Casey's go-to villains during his early Marvel work. I'm not really sure what that says about Casey, except that he was a fan of underutilized adversaries -- or maybe that he had a thing for freaky circus folk.

'99 saw the release of Mister Majestic, co-written by Brian Holguin. McGuinness handled the art on the action-packed first six issues. The series started with Majestic literally rearranging the solar system, to make it unrecognizable to a pending threat. It only got crazier from there, with temporal distortions, a date with Ladytron, space sirens, an alien prison ship crashing into Earth, and an escapee attempting to assimilate into Earth's culture (to eventually conquer the planet, 'natch) by watching crappy sitcoms and commercials. There was also a heartfelt tribute to Majestic's son, Majestrate, whose body did not survive their landing on Earth decades ago but whose mind did. A revival proved all too brief, as the "starstuff" that allowed for the resurrection also created an inter-dimensional imbalance. Majestrate sacrificed himself to save the world, a hero's death but one that put Majestic into quite a funk for years to come.

The final three issues marked a total tonal shift for the series. With art by Eric Canete (who also did the occasional fill-in on Deathlok), Casey and Holguin took a turn for the trippy. The Universals, a group of god-like aliens, tapped Majestic to join their league. Upon accepting, they imbued him with cosmic power, and he became a full-on protector of the universe, leaving Earth to defend all of space. The arc marked Casey's first real crack at cosmic action -- and caused Majestic to ultimately lose his hard-earned humanity.

Around the same time, Casey also got his nostalgia on in the first of his "secret history of..." projects for Marvel. X-Men: Children of the Atom revealed the early days of the first class, before the events at Cape Citadel. Scott was a scrappy introvert, an orphaned runaway still reeling from his encounter with Jack O'Diamonds. Bobby was a shivering social outcast, possessing so little dexterity with his powers that he nearly flooded his house with snow. Hank was the golden boy -- the big-brained all-American athlete -- turned outsider when he revealed his powers at a football game. And, Warren was a confident hero, the only one in the mix, thanks to his brief solo career. They were, at best, a ragtag team, but they managed to pull together and thwart an anti-mutant gang.

Steve "the Dude" Rude drew the first three issues, which drew parallels to Columbine, due to the high school setting and the attacks on mutants. After a six month (!) hiatus, the series returned, with art by Paul Smith and Michael Ryan on one issue and Esad Ribic on the remainder. The shift in art matched the series' shift in focus, from high school life to full-on action.

If Children of the Atom isn't considered canon -- and, given the liberties taken with the X-Men's origins (like Scott, Hank, and Bobby all attending the same high school), I doubt it is -- it's essentially an early crack at Ultimate X-Men, before "ultimate" even entered the Marvel lexicon.

Casey's always ahead of his time.

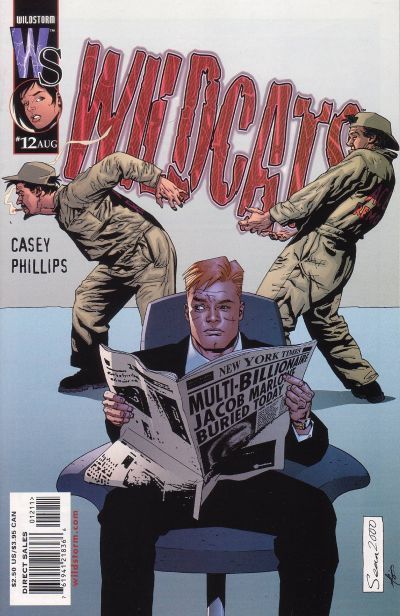

That forward thinking was never more prevalent than during his tenure on Wildcats. After co-writing a handful of the second volume's issues with Scott Lobdell, Casey's run, with Sean Phillips, began in earnest with #8. If you were into puns, you might say it got off to a bang, with Kenyan -- an evil immortal alien -- eating a bullet, marking the end of the 'cats crusade against evil aliens. Lord Emp, the leader of the Covert Action Team, had sought Kenyan out to bring about his own death, a process which would also kill Emp's murderer. Desiring to die, to ascend to whatever higher plane, Emp turned to Spartan, whose android body couldn't technically be killed. Emp's death marked the start of an entire overhaul for his team, who subsequently eschewed covert action.

Spartan rechristened himself Jack Marlowe, after Emp's Earthly identity, Jacob Marlowe, and inherited his father-figure's fortune. Newly wealthy, Jack Marlowe sought non-violent means of saving humanity and created the Halo Corporation. Cole Cash, believing Zealot was dead, fell into a mild depression, one filled with lookalikes of his lady love, booze, and english muffins (Cash takes his with margarine, FYI). His eventual reunion with Zealot was fraught with action (of more than one kind) and presaged the coming Coda War. Jeremy Stone (the once and future Maul) and Priscilla Kitaen (Voodoo to you) settled into a quiet life together. He secretly shrank his body, thereby enlarging his intelligence, to try and find a way to separate the Daemonite from her body. Thankfully, he didn't succeed, for a super-powered killer attacked them, chopping off Pris' legs and blinding Jeremy. Coming to grips with her Daemonite side eventually allowed Kitaen to regrow her limbs. Agent Wax, a member of the National Park Service (which is actually a formidable threat in the Wildstorm universe), was introduced. Ladytron also returned, only to be be deconstructed, then reconstructed by Noir, an arms dealer turned Halo associate. Noir attempted to use her to kill Marlowe and take control of his corporation. Ultimately, all he actually did was provide Marlowe the means to create a better world: an ever-lasting battery.

Wildcats, volume 2, was a time of transition, from spandex to suits, from saving the world to living "ordinary" lives, from covert action to corporate meetings. And, it was absolutely astounding. Personalities were valued over powers. Stories were dictated by personal growth (with the occasional super-killer thrown in for good measure). The characters felt like living, breathing people, with foibles and agendas of their own. They were a post-modern team in a post-modern series.

And, they became a hyper-modern team in a hyper-modern series when the book was relaunched as Wildcats, Version 3.0. Noir's ever-lasting battery skyrocketed the Halo Corporation into success. Marlowe became a corporate king, watching a better world come to fruition, one product at a time. The Halo line expanded to include cars that ran without gas and computers that would never need upgrades or replacement. Cash and Wax agreed to aid information broker C.C. Rendozzo in her quest to find her son, only to run afoul of Agent Orange, an android killing machine. Cash's legs were riddled with bullets, and he was confined to a wheelchair, which only strengthened his resolve. He trained Edwin Dolby, a Halo accountant, to be his stand-in in the field. Wax remained with the Park Service, keeping an eye on the government's machinations for Marlowe. Wax, a hypnotist, disguised himself as his boss at the Park Service and slept with that man's wife; when his boss found out, Wax convinced the man to kill himself and then took command of the agency, still disguised as his employer. Ladytron came back into action, with Cash in control of her body, just in time for the Coda War, which once again reunited Cash and Zealot. Marlowe abstained from the violence and teleported the survivors to safety when the dust settled. In the end, he decided to take the team and Halo in a new direction.

What that direction was, we'll never know, for the series was cancelled, due to low sales. A major artistic shake-up didn't help matters. Dustin Nguyen handled the art on the first sixteen issues of the series, and his sleek style was perfectly suited for the high-gloss corporate world. He left the series to take a crack at his dream gig, Batman, and planned to return with #25. In the meantime, Francisco Ruiz Velasco was supposed to take over; he lasted about an issue and a half before departing. Pascal Ferry drew a high-octane Coda War issue, and Duncan Rouleau finished the series off. The constant transitions were jarring, and the final arc lost some of its impact as a result.

Still, Casey managed to take a covert action team, dismantle it, and turn it into something entirely new and different: a corporate comic, a series about socio-economic impact, an entirely unique invention. No amount of artistic inconsistency could have stopped that vision.

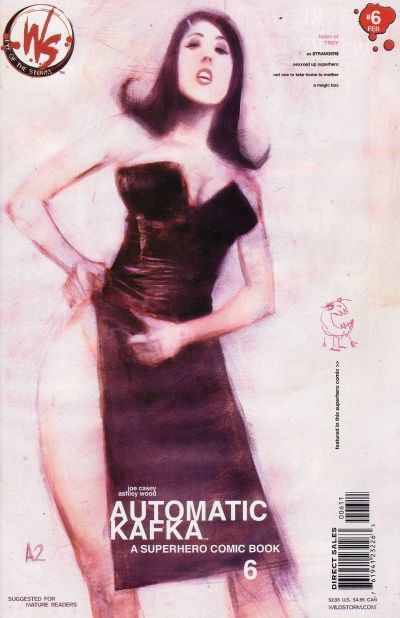

Casey expanded his mind and the comics form with Automatic Kafka, which ran concurrently with the start of 3.0. With Ashley Wood, Casey dove into the life of the titular retired hero, a robot who got mixed up in sex, drugs, and fame. He wanted to be human. He wanted to experience real emotions. He wanted to laugh. He was Pinocchio in tin skin. He got a second shot at his fifteen minutes...as a game show host. And, then, he got cancelled. Casey and Wood broke down the fourth wall and delivered the news themselves. Kafka wasn't commercial enough, so his time was up. He was a failed experiment, but, hey, interesting failures are often more worthwhile than the same-old-same-old, right?

The series was a skewering of everything American: its obsession with celebrity, its obsession with porn, its obsession with youth, its obsession with game shows.

It was also perhaps the most twisted send-up to the Avengers ever. Kafka can easily be seen as an analogue to The Vision, a robot longing to be human. The Constitution of the United States is a patriotic war hero, whose sidekicks -- a revolving door of scantly clad girls, who take on the moniker The Declaration of Independence -- have a propensity for dying. Of course, Cap never became a pornstar. Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman in the world, turned out to be an old lady, using sex-magic to stay young. She and Kafka had an intense sexual encounter, but she didn't get pregnant and go crazy, like Vision's magic lady love.

An adult Charlie Brown -- still down on his luck, after all these years -- appeared, as a contestant on Kafka's game show, The Million Dollar Deal. Seeing the Peanuts all grown up, if not all that much mature, was positively surreal. But, then, so was the whole series.

Kafka is definitely a comic you should own.

While Casey was experimenting freely at Wildstorm, he also took on a bevy of projects in the early days of the new millennium.

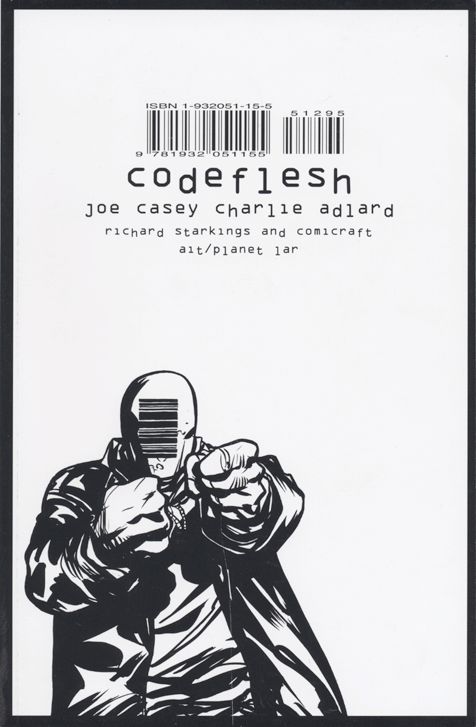

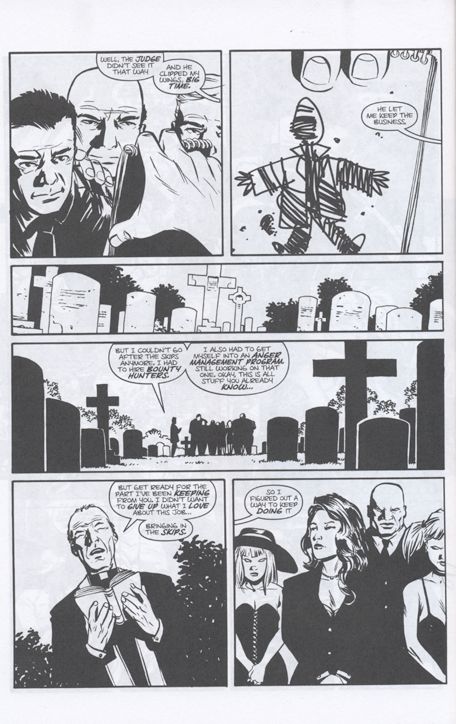

Codeflesh told the tale of Cameron Daltrey, a bail bondsman in L.A. -- an L.A. overrun by supervillains. He doubled as a bounty hunter, wearing a mask adorned with a barcode, and tracked down those criminals who didn't show up for their court dates -- criminals like the oversized Slug and Rotor, who took augmentation to the extreme. Skip tracing ate a solid chunk out of Daltrey's time, and his relationship to Maddie, a kindly stripper, suffered. All of the dialogue in the final issue is comprised of Daltrey's letter of explanation to his lover. It's a fascinating read, in which Daltrey's confession -- his open emotional release -- juxtaposes with the ongoing narrative, including the funeral scene above and a brutal battle. Only in comics would such a style work.

Charlie Adlard drew the series, which was serialized first in Double Image and then in Double Take, flip-books both. The latter also featured Rex Mantooth! Kung-Fu Gorilla. Casey, Fraction, Adlard, and Kuhn all cutting loose in one book? Yeah, that's gotta be one of the best series of all time.

Casey also nabbed the writing chores on two top properties: Adventures of Superman and Uncanny X-Men.

In AoS, he turned the Man of Steel into a pacifist. Sure, he'd save the day -- on pretty much a monthly basis -- by flying into suns or burrowing to the center of the Earth to plant a white dwarf fragment to temporarily restore gravity to the planet, but he rarely resorted to fisticuffs. In fact, in Casey's final year on the book, Supes never threw a punch. Casey didn't want Superman to be just another professional wrestler in spandex, grappling with the villain of the month. The Man of Tomorrow was better than all that.

Casey also busted open his idea box and chucked everything at the Big Blue Boy Scout. Lex Luthor suffering from dementia (and wearing a ridiculous wig). Doomsday's return. A new Persuader. Mxy twins. Fiction come to life. A whole town of heroes. A sinking sub. The Golden Age Superman. And, my favorite ne'er-do-wells, the Crime Syndicate of Amerika -- the Morrison/Quitely variants, that is.

When his thirty-five issue stint on the series wasn't interrupted by crossovers, often handled by entirely different creative teams, Casey partnered with everyone from Ringo to Pete Woods to Carlos Meglia to Derec Aucoin, who eventually became the series' regular artist.

Casey's stab at the X-Men, in Uncanny, wasn't well received by many fans for reasons I've yet to fully grasp. (Me? I always always behind it.) His first arc had a split focus between the team coming to the rescue of a band of English Morlocks (lovingly referred to by readers as "The London Lepers") and a tarted-up pop starlet, dating Chamber to seem more edgy for the press. Once again, celebrity got skewered. At least Jono got laid, as part of Casey's plan to "sex up" the X-Men. #399 introduced the second phase of that plan: the X-Ranch, a mutant brothel in Reno, Nevada. Among the working girls was Stacy X, a snake-skinned mutant with tactile pheromone control. One touch -- or one lick, from her forked tongue -- and you were a puddle. Just ask Bobby Drake, who infiltrated the Ranch as music exec Mr. Friese. Stacy -- a hooker without a heart of gold -- was meant to be a virgin, using her powers to bring pleasure to her johns rather than actually performing sex acts. It was a clever conceit, but one Casey never expressly stated in the series, so the idea was never used. Alack.

The Church of Humanity, a band of anti-mutant, religious fanatics, made short work of the X-Ranch. They weren't exactly the most subtle villains, but religious fanatics rarely are.

Casey created the X-Corps, as well, a group of European mutants who sought to police mutant activity. Banshee, reeling from the death of Moira MacTaggert and the dissolution of Generation X, led the squad. Former GenXers Jubilee, M, and Husk followed, as did mind-controlled villains like the Blob and Avalanche. The group barely got a chance to function, to see if their more intense methods were more effective than Xavier's, before Mystique sabotaged the team.

Vanisher also reappeared, this time as the head of a drug cartel, peddling mutant growth hormone. Warren Worthington put the kibosh on Teleford Porter's plans without even lifting a finger. He simply had Worthington Enterprises buy off Porter's employees and halt distribution. The solution was completely in line with the corporate maneuvers from Wildcats Version 3.0.

And, in fact, it should come as no surprise that Casey wrote the best Archangel in ages. He was a confident businessman, completely at home in the battlefield and the boardroom. Casey's Iceman was also pitch perfect, a casual, conversational team player, using his nondescript looks to hide in plain sight (as that ad exec or a waiter or what have you). Nightcrawler was in full-on priest mode, complete with crisis of faith. And, Wolverine was, well, Wolverine. Interestingly, there was no clear-cut leader for the team. Frankly, they hardly needed one. Each member of the team (excluding Stacy X) was a seasoned veteran and knew exactly what to do during a confrontation. It was second nature to them.

UXM had its share of artistic woes. Ian Churchill drew all of three issues, before deciding he wasn't right for the project. Sean Phillips laid out the next batch of pages, for Mel Rubi (who partnered with Casey on the KISS comics revival) and Ashley Wood to finish. Wood also handled the art on the annual, which reintroduced Vanisher and was presented in Marvel Scope. Ah, gimmicks. Tom Raney and Tom Derenick tag-teamed on #399. A total of six artists jammed on #400. Ron Garney came on for an issue or two, including Casey's entry in the much-maligned Silent Issue event, then jumped ship to get a head-start on Chuck Austen's scripts. Aaron Lopresti and Phillips rotated issues during the X-Corps, and Phillips finished off Casey's run. -WHEW-

Since leaving the series, Casey's apologized profusely for what he feels was a mistake on his part: taking on the assignment without being a true fan of the characters. If nothing else, UXM taught him to only write projects in which he was entirely invested.

The Intimates was one of those. Co-created with Jim Lee, the series was an honest look at superhero high schools. There were no villains, no end of the world scenarios, no big, dumb fights. No, there were a group of kids, who were trying to figure out who they were and what they wanted to do in life. There were clashing personalities, failed romances, misunderstandings, and all that emotional turmoil you remember from high school. It was the antithesis of The Ultimates, focusing on personal interaction instead of widescreen action. It was heightened reality. And, it was only supposed to last eight issues. Then, it got stretched to twelve and cancelled anyway.

Giuseppe "Cammo" Camuncoli drew the meat of the series, with Jim Lee providing covers (for a time) and the odd panel from the comic-within-a-comic, Supersonic Espionage Boom. Cammo's light, quasi-manga style was a strong match for the cast of characters: Punchy, the faux-ghettoism-spouting loudmouth with the power-punching nun puppet; the Duke, the all-American football player, under entirely too much pressure from his father; Destra, the beautiful snob who spat explosive fingernail clippings; Empty Vee (say it fast, and it sounds like a certain "music" station), the shy, overweight girl who struggled to stay visible; Sykes, whose head was encased in a malleable null-field that reacted to his surroundings and prevented those in his vicinity from getting swept up in psychedelic madness; and Kefong, who rocked Bruce Lee's Game of Death tracksuit and created temporal bubbles. Each was distinct, in both personality and appearance.

So, naturally, Cammo left the series, and Wildstorm threw whoever was on hand at the book, including its intern, Scott Iwahashi. His work was remarkably accomplished, but he didn't last. Carlos D'Anda and Ale Garza also cycled through. By the end of the series, the ticker at the bottom of every page -- where Casey offered background info on characters, creator commentary, tongue-in-cheek teen survival tips, and plugs for other series -- was rife with sarcasm and vitriol. The metatextual device was pure creator commentary, and he was non-plussed.

It was refreshingly honest. It was also rather reassuring to know that Casey had the same qualms about the changes as his readers.

Casey hasn't worked for Wildstorm, the imprint where he created some of his most successful works, since The Intimates ended.

Nevertheless, the series worked. It was as true to the high school experience as one is likely to find in American superhero comics.

In 2005, Casey relaunched G.I. Joe, with rising star Stefano Caselli, for Devil's Due. And, once again, change was in the air. Hawk was paralyzed. General Joseph Colton, the original G.I. Joe, took command. The team shrank. Their HQ was relocated to Yellowstone National Park. Vance Winfield returned. Destro proved a formidable foe. Snake Eyes died -- at least temporarily. Duke was a man possessed. Casey's run was an intense eighteen issues of realistic action.

2005 further saw the release of GØDLAND, Casey's ongoing cosmic opus, with Tom Scioli. It's written in the old Marvel manner, with Casey providing the plot, Scioli providing the art, and then Casey providing the dialogue and thought balloons and so forth. It's a true collaborative effort.

The series details the exploits of astronaut Adam Archer, who was transformed into a cosmic being by the Cosmic Fetus Collective during a mission to Mars. With his three sisters -- Neela, a fellow astronaut and military commander who resents her brother's abilities and fame; Angie, a rebellious fighter pilot; and Stella, who keeps the lines of communication open and a clear head -- he saves the world, despite the distrust of the government and much of the public. The giant, canine-esque Maxim accompanies Archer on many an adventure, in effort to prepare the astronaut for his destiny.

As captivating as the heroes are, it's the villains that steal the show, every time. Friedrich Nicklehead, a floating skull in a jar after the ultimate high, is probably the character find of the century. He spouts the best off-the-wall dialogue. And, he now sits atop the beheaded body of Discordia, the daughter of the Tormenor, another nasty piece of work. The Triad -- a trio of robots from outer space -- are currently up to no good. Called Ed, Eeg-Oh, and Supra, they fall in line with Freud's postulated components of the mind and quickly cop to human behavior.

The book is pure, Kirby-flavored fun.

Also in 2005, Casey partnered with co-writer Caleb Gerard and artist Damian Couceiro to present the greatest high concept you wish you thought of: werewolves on the moon. Full Moon Fever, baby. Astronauts ravaged by lycanthropes. Only from AiT/PlanetLar.

A year later for AiT, Casey, with Adlard, trotted out Rock Bottom, the tragic tale of a pianist who's turning to stone. Adlard switched up his style for the project, dropping out the spotted blacks and adding rough texture and shade to the art to portray the pianist's plight.

Recently, Casey's been going back to the nostalgia well to offer new insight on the early days of the mainstays at the House of Ideas. With Scott Kolins, he detailed the formation of the Avengers in Avengers: Earth's Mightiest Heroes and filled in some further gaps in its sequel, with William Rosado. The days after the Fantastic Four were bombarded with cosmic rays and crashed back to Earth were chronicled in Fantastic Four: First Family, with Chris Weston. And, Iron Man's first encounter with the Mandarin is being fleshed out, with Canete, in Iron Man: Enter the Mandarin.

Casey already proved himself to be an expert at penning the further adventures of Tony Stark in Iron Man: The Inevitable. The miniseries introduced a new Spymaster, wealthy industrialist Sinclair Abbot. He was literally Tony's opposite number, complete with super-suit. Abbot was content to trade barbs and insult Stark at fundraisers for much of the mini, however, leaving it up to his hired lackey, the Ghost, to ruin Stark's life. An incorporeal Living Laser also caused quite a bit of havoc. Stark was nearly driven to drink again, but cooler heads -- and repulsor rays -- prevailed. Frazer Irving provided the stunning visuals.

Casey teamed with Kevin Maguire earlier this year on Velocity, an entry into Top Cow's pilot season. No word yet on whether or not they won, but, if so, expect some more straight-up superhero fun.

In addition to print comics, Casey -- along with the other members of Man of Action, Steven T. Seagle, Joe Kelly, and Duncan Rouleau -- penned the online accompaniment to NBC's hit Heroes. You can find out more about that series here.

The Man of Action team also created Ben10 for Cartoon Network and has new shows in development.

Next year, Casey's primed to release a whole slew of series. From Image, he's got Krash Bastards, an OEL manga, featuring future samurai, with Axel Ortiz; Nixon's Pals, a graphic novel about a supervillain parole officer, with Chris Burnham (of Ten Ton Studios, home to Cable & Deadpool's Reilly Brown, The Incredible Herc's Khoi Pham, and Comic Book Idol runner up, Charles Paul Wilson III; damn, that place is overflowing with talent); and a revamped, streamlined Youngblood ongoing, with Derec Donovan (nee Aucoin). Celebrity superheroes? Yeah, that's right in Casey's wheelhouse. He'll also reviving Flip Falcon, with Bill Sienkiewicz, for Image's Next Issue Project. And, who knows? Charlatan Ball -- starring Chuck Amok, a reality-hopping stage magician -- might even get released. Artist Andy Suriano has been hard at work on that book for years now.

Plus, Casey and Jim Muniz will team for The Last Defenders for Marvel. She-Hulk and Blazing Skull? I'm there.

And, maybe Warhead -- described as "Patton in space" -- will finally see the light of day. I think Ian Richardson was working on that one.

2008 is primed to be a busy year for Casey, but I'm pretty sure he wouldn't have it any other way.

If you've made it this far, congratulate yourself by checking out The Basement Tapes. Casey and Fraction's year-and-a-half-long look at the comic industry, from the inside. It was the best thing going, for as long as it went.

Want more Casey? You crazy martyr! Check here and here. Or here. Or here. Or here. Or here.

And, he describes his love for team books here.