It's a miracle that Bill Reed hasn't read this Reason ...

9/15/07

258. Miracleman.

Alan Moore deconstructed superheroes in Watchmen, but he began examining superheroes and how they really worked with Miracleman, an old British knock-off of Captain Marvel that Moore made his own. Marvelman, as he was called in Britain (changed for American audiences because nobody wanted to piss off that big company in New York), was created in 1954 when Fawcett couldn't publish Captain Marvel anymore, therefore depriving the poor Brits of Shazam! reprints, which were immensely popular in the old country. Marvelman's adventures were published between 1954 and 1963, when his popularity waned and he faded into obscurity. In 1982, in order to launch Warrior, his new comics anthology magazine, Dez Skinn gave the character to Alan Moore, who turned the whole thing on its ear.

Moore is a great writer because he thinks of how superhero stuff really works and makes it believable. His most famous retcon is Swamp Thing #21, where the creature learned that he wasn't man encrusted with plant life, but an actual sentient plant. But Moore's explanation for how Miracleman could switch from a small boy to a superhero was intriguing, too, relying on science (the comic-book kind, but science nevertheless) rather than magic. He decided that Mike Moran, the young boy who said a magic word and became Miracleman, was actually moved to another dimension and his mind transplanted into the body of a cloned superhero. This was part of an experiment by the mad scientist Dr. Emil Gargunza, who kidnapped orphans for his purposes. He kept them sedated and created a "comic-book world" for them, which explained the original run of the book. When the experiment ended, Mike Moran was thrown out into the "real" world. Twenty years later, during a hostage situation at a nuclear plant, he remembers his "magic word" and transforms back into Miracleman.

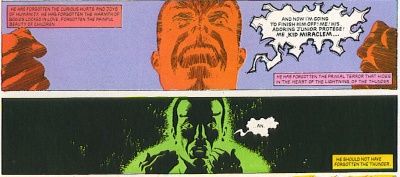

Moore used this character to look at the effect of superheroes on the real world. Miracleman has an arch-enemy, of course, in the form of Kid Miracleman, his former protg. Kid Miracleman, whose real name is Johnny Bates, has become a powerful businessman, but he's also insane, and Miracleman's return sends him over the edge. Their first battle is just a prelude to their epic fight later in the book, but it's an indication of what Moore is doing with the title, as their fight is truly what a superhero battle would look like. Kid Miracleman accidentally says his "magic word" and reverts to Johnny Bates, who is still a boy. Miracleman can't kill him, and Johnny is sent to a school for orphans.

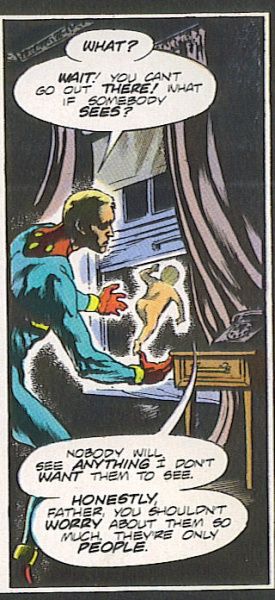

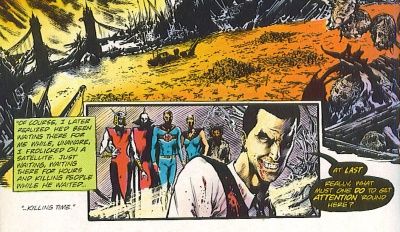

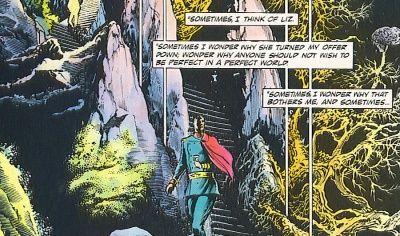

Later issues showed Miracleman tracking down Emil Gargunza, meeting Miraclewoman, and getting his wife pregnant and watching her give birth,but the series really became legendary when Moore teamed with John Totleben and wrote "Olympus," the final stage of his examination of superheroes. Miracleman, joined by Miraclewoman, meet the aliens from whom Dr. Gargunza stole the cloning technology and discover that they need to evolve or die. Before they can go public with their powers, Kid Miracleman gets out and goes on the most horrific killing spree we've ever seen in comics. He slaughters everyone in London while he waits for Miracleman to notice him. Their battle is the most intense superhero fight ever, putting to shame anything we've seen since, even the ones that strive for "realism." Miracleman wins, with the help of his allies, and this tragedy spurs them on to recreate the world under their dominion. Miracleman has become a god. Of course, some might argue that he loses his soul in the process.

Moore left the book and Neil Gaiman took over, crafting a group of short stories titled "The Golden Age." They're curious stories, well done and technically excellent, but it's difficult to write a story about gods once they've taken over the world. You need conflict in stories, so Gaiman focuses on the people living in the brave new world. After this brief caesura, Gaiman began "The Silver Age," which was apparently going to start to unravel Miracleman's paradise, but two issues in, the book vanished. It hasn't been seen since. What happened?

Two words:"Todd" and "McFarlane." McFarlane, flush with cash from drawing impossibly pneumatic supermodels with gargantuan hairin Amazing Spider-Man and from suckering someone to get Martin Sheen to star in amovie starring his character, bought Eclipse when it went under (boy, wouldn't it have been nice if he had just settled for buying ridiculously overpriced baseballs?). Through legal issues I'm not even going to try to understand, this gave him ownership of two-thirds of Miracleman, with Gaiman and artist Mark Buckingham owning the other third. After Gaiman wrote something for McFarlane in Spawn (I own that issue!), the two had a falling-out over the rights to that character (they're fighting over Angela?really? it's like that episode of Cheers where Chandler and Ross are arguing over who came up with the joke in Playboy until Monica points out it's a stupid joke, after which they deny ownership; in the case of Angela, toparaphrase Ms. Bing-Geller, Gaiman and McFarlane shouldn't be arguing over credit, they should be assigning blame ... but I digress) and they've been a-fussin' and a-feudin' ever since, and poor little Miracleman has gotten trapped in the middle. Boo, Gaiman and McFarlane! Someone sued someone else, the lawsuit went on for a while, and nothing was settled. McFarlane, of course, is desperate to make a "Miracleman-coupling-with-Miraclewoman-while-flying" action figure, you know, for the kids. Gaiman, meanwhile, really wants to write the scene where Dicky Dauntless goes on a raping spree just to get the taste of Miracleman's kiss out of his mouth. Can't we all just get along?

So Miracleman, as much as Flex Mentallo, remains a Holy Grail of comics. Moore's sixteen issues are stunning, despite some ragged ones in the middle - with, perhaps not surprisingly, a young Chuck Austen on art (under a pseudonym, of course - it was only later that he was confident enough to destroy comics under his own name). I've heard that, unusually enough, the trade paperbacks are more valued than the original (Eclipse) issues (of which some were reprints of the Warrior stories), because they're out of print and have been for years, while you can still pick up the individual issues in dusty comic shoppes worldwide. Heck, my retailer had them all as a package not long ago for fifty bucks. Maybe McFarlane and Gaiman will get their heads out of their asses in the near future and bring us new books, or at least new printings of the trades. They really are wonderful comics (well, if you define "wonderful" as a super-villain spiking heads on street signs because he's "bored," which I, as the nihilistic bum I am, do) that stand tall even 25 years later.

Wikipedia has a decent run-down of the ridiculously convoluted story of Miracleman's rights. Don't hold your breath waiting for a resolution. I would also suggest getting Kimota!TheMiracleman Companion by George Khoury, which is a fantastic in-depth look at the history of the character. If you can find it, as it appears to be out of print (I know, shocking that something to do with this character is out of print).