A column in which Matt Derman (Comics Matter) reads & reviews comics from 1987, because that’s the year he was born.

Strange Tales #1-7 (Marvel) by Bill Mantlo (#1-6), Peter Gillis, Bret Blevins (#1-6), Chris Warner (#1-4), Larry Alexander (#5, 7), Terry Shoemaker (#6-7), Al Williamson (#3), Bob Wiacek (#6), Gerry Talaoc (#7), Randy Emberlin, Christie Scheele (#1, 3), Glynis Oliver (#2, 4-6), Paul Becton (#7), Bob Sharen, Ken Bruzenak, Jim Novak (#1-3), Janice Chiang (#4-5, 7), Ken Lopez (#6), Carl Potts

With a book like Strange Tales, where every issue is divided between two different narratives (or any number of narratives, but in this case it's just the two), you always want some sort of connection to tie the stories together, something to bring unity to the title. Obviously the stories should work individually as well, but it's nicer when there's a bond between them, an identity to the series as a whole that fits with each section's own goals and attitudes. Strange Tales is split evenly every issue between Cloak and Dagger and Dr. Strange, the two titles which it replaced. Because they're both continuations of previously existing comics, it would be understandable if there wasn't a ton of cohesion between their respective outlooks or aims. Whether through editorial design, creator collaboration, or sheer dumb luck, though, the two halves of Strange Tales find common ground almost immediately, and continue to examine the same core concept, though still in their own ways, right up through issue #7 where their narratives actually collide and briefly become the same. Both Cloak and Strange wrestle with remaining heroic while sometimes needing to act unheroically, and this struggle quickly becomes the center of Strange Tales. But the two men deal with their shared problem differently and end up in different places because of it, so their stories stand apart even as they come together, thematically and literally.

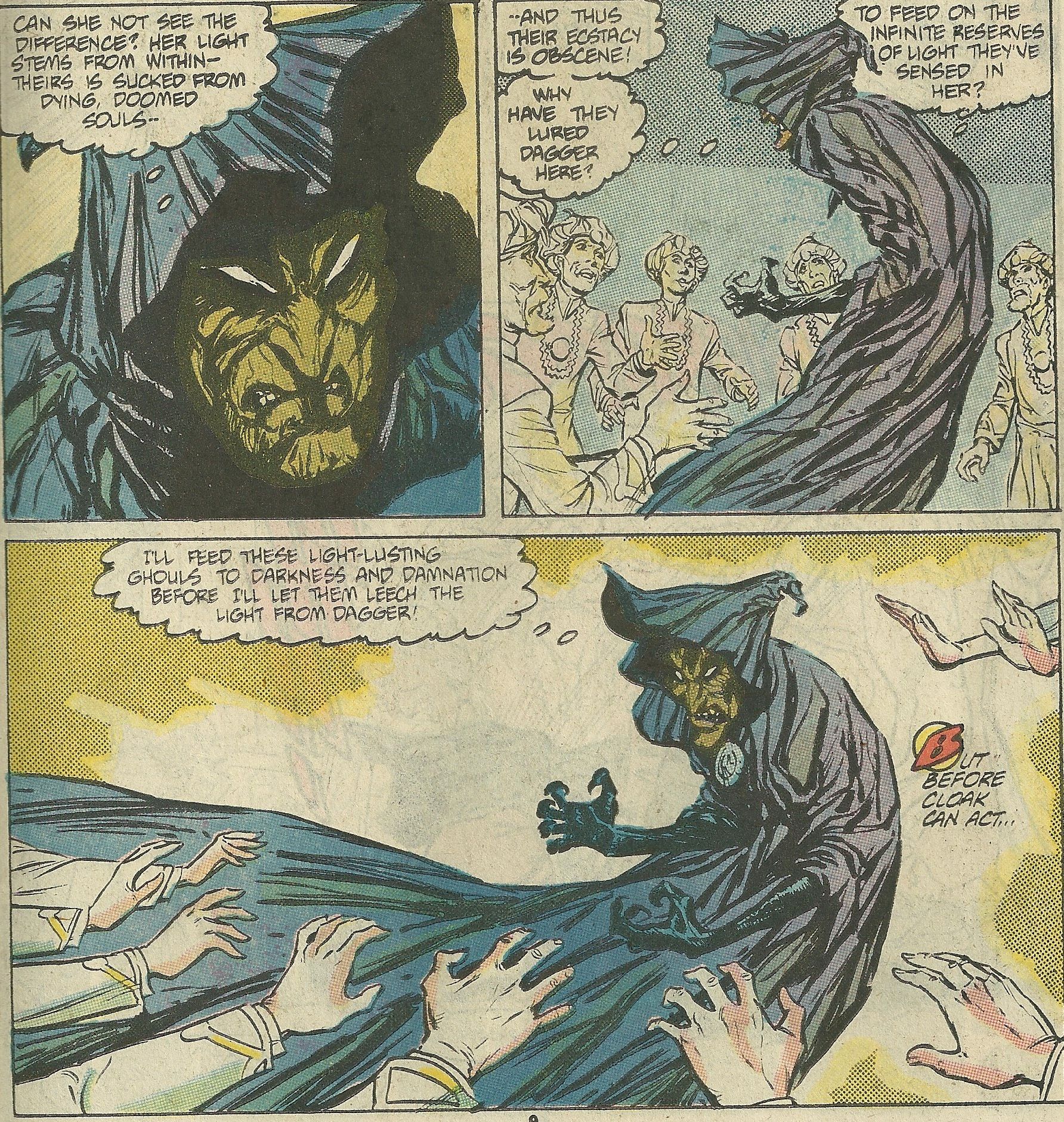

For Cloak, the problem is that his power set encourages him to explore his evil side. He is a living portal to a strange "dark dimension" that causes anyone who enters it to see and experience their own worst fears. This darkness also drains the life energies of the people inside, with the potential to sap them completely and do permanent, even fatal damage. Cloak literally hungers for the light of other people's life forces, and it is only because Dagger's powers are a physical manifestation of that light that he is able to stay sated most of the time. Without her, he would no doubt need to find new victims on which to regularly feed, a vampire of sorts, but with an even scarier means of sucking them dry than the usual fangs in the neck. Cloak recognizes this terrible, gnawing need within himself, the constant craving he carries everywhere, and it is not always easy for him to resist. When someone threatens Dagger, whom Cloak deeply loves, his automatic response is to want to get rid of them for good, to surround them in unending, horrifying darkness and never let go. It would be easy for him to do and, more to the point, it would be highly satisfying, because he'd be protecting Dagger and quelling his hunger at once. Indeed, if anyone angers Cloak at all, even in a relatively minor way, some part of him always wants to subject them to the full force of his powers because he can never escape the incessant, nagging need to refill and refuel. He's in a perpetual state of wanting, nay, requiring more of the light of life to be extinguished within the folds of his cape, and the only way for that to happen is for him to attack and mentally torture other human beings.

Yet Cloak knows he can never fully surrender himself to the worst of his impulses and desires, for his own sake and for the sake of his relationship with Dagger, fraught as it is already. Her powers, as I mentioned, are the exact opposite of his, creating thin blades of light made out of the same energy upon which Cloak feeds, and as such she possesses all the kindness for and trust in others he finds so elusive. While Cloak's unending emptiness pushes him to use his powers as often as possible and see everyone as a potential target, Dagger's excess of life and light makes her overly empathetic, wanting to find the good in everyone, to understand all sides of any conflict. This is part of what Cloak admires in Dagger, and it's also what keeps him in check. He realizes that if he gave into the darkness, he would lose her forever, because she couldn't continue to live and work with someone so angry, destructive, and dangerous. So her powers help him maintain some level of fullness, and he tries as hard as he can to only use his abilities against only those who deserve it, and even then in moderation so as to never sink to any depth from which he can't return.

You can see Cloak's strain to stay well-behaved very clearly in the art by Bret Blevins, who pencils the Cloak and Dagger parts of the first six of these seven issues (the same six issues which co-creator Bill Mantlo scripts). Blevins depicts Cloak with an almost pained look on his face at all times, an agitated snarl he can never shake. His face is also covered in thick, deep lines that appear to almost cut into his flesh, like a weird mask of wire pulled too taught. The wrinkles of his costume have that same weight to them, so that despite the free-flowing nature of his movements, he looks like he's wrapped in a bizarre, flexible cage of of darkness. It is the physical representation of Cloak's inner turmoil, the lines acting as visual reminders of his inescapable hunger and all the effort he exerts to fight against it, to maintain control.

While Cloak is occupied keeping his wicked thoughts at bay, Dr. Strange finds himself acting more wicked than ever before, not because it appeals to him but because he sees no other viable means of defeating his foes. In battling an evil wizard named Urthona, Strange had to sacrifice all of his "objects of power," which meant destroying many items that acted as barriers, prisons, or other containment devices for various powerful evils. That all happens immediately prior to Strange Tales, in the pages of Dr. Strange, so that's the status quo as soon as we're introduced to Strange in this series: unknown and mighty forces of darkness have been released back into the world, and Strange knows he's the one responsible (and probably the only one capable) of capturing them all again, if not killing them. Trouble is, Strange's objects were also a big part of where he got his magic mojo, so he's considerably weakened, and of course he doesn't have the things that defeated these insanely powerful baddies in the first place. It's a disadvantageous position to say the least, and it takes its toll right away.

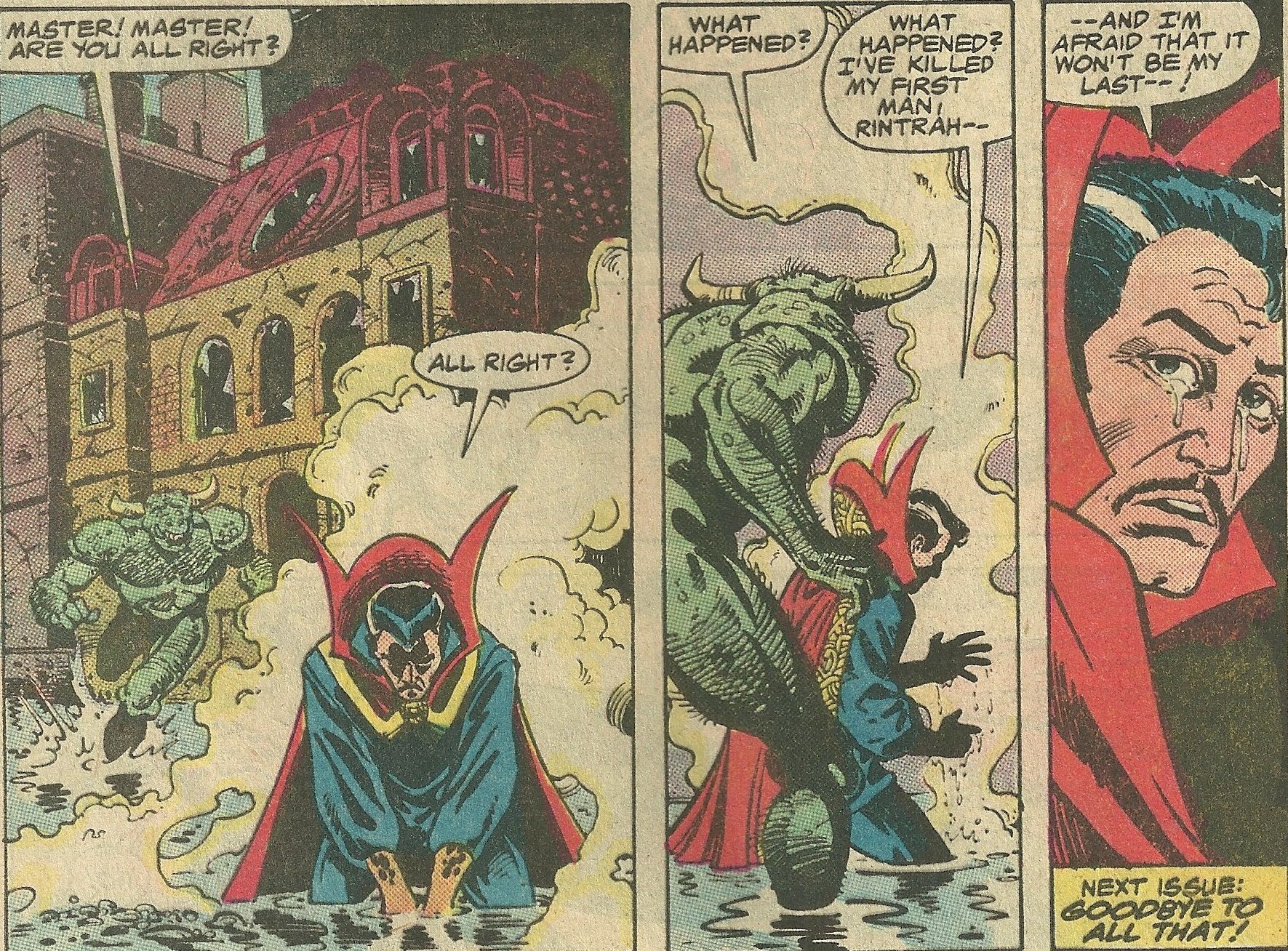

The first confrontation Strange has is with a water elemental, an entity that, as one of its many tricks, inhabits a host body and controls it, using it mostly as a mouthpiece, and as a defense against Strange. The elemental knows Strange won't want to kill the innocent human host even if that's the only way to win, openly mocking him about it while they fight, feeling certain it can't lose so long as Strange refuses to cross that line. Turns out that's actually true, but what the elemental doesn't count is on Strange deciding to go for it, so Strange takes a life and wins the fight, but loses a certain piece of himself in the process, and deals in dark magic for the first time. It's far from the last, as each new challenge he faces forces him to do it again. Not always by killing somebody, because that would get boring, but Strange finds that he needs evil magic to stand a chance against such evil beings, especially with his usual methods no longer available and his remaining good magic not up to the task.

Strange and Cloak have sort of mirrored relationships with their inner darknesses, the former embracing it despite it running counter to his desires, the latter fighting it while knowing it's the center of his very being. Neither are comfortable with it, neither want it to be part of their lives, because they're both good people in the end, but they begin in opposite positions and try to move in opposite directions. When they end up joining forces in Strange Tales #7, the question then becomes, what is the book's ultimate stance on all of this? Does it believe in fighting against our worst urges to try and become better people, however hard or unnatural that may be? Or does it think that sometimes, acting badly is necessary to prevent even more awful things from happening? Surprise surprise, the answer is both.

The reason Dr. Strange teams up with Cloak and Dagger—and the New Defenders, actually, but that's one of many tangents I'm avoiding—is that Strange's old foe Nightmare figures out a way to trick Cloak and use his powers to set a trap for Strange. Evidently the dark dimension in Cloak's cloak borders Nightmare's own realm, so he contacts Cloak via dreams, pretending to be someone imprisoned in the dark dimension and promising that, if freed, he'll make Cloak a normal human again. But how to free him? Why, with the help of Dr. Strange, of course! Cloak eventually heads to Strange for help, and as soon as they're close enough to each other, Nightmare breaks through Cloak's dimension into our own and grabs Strange, pulling him and everyone else into Nightmare's world.

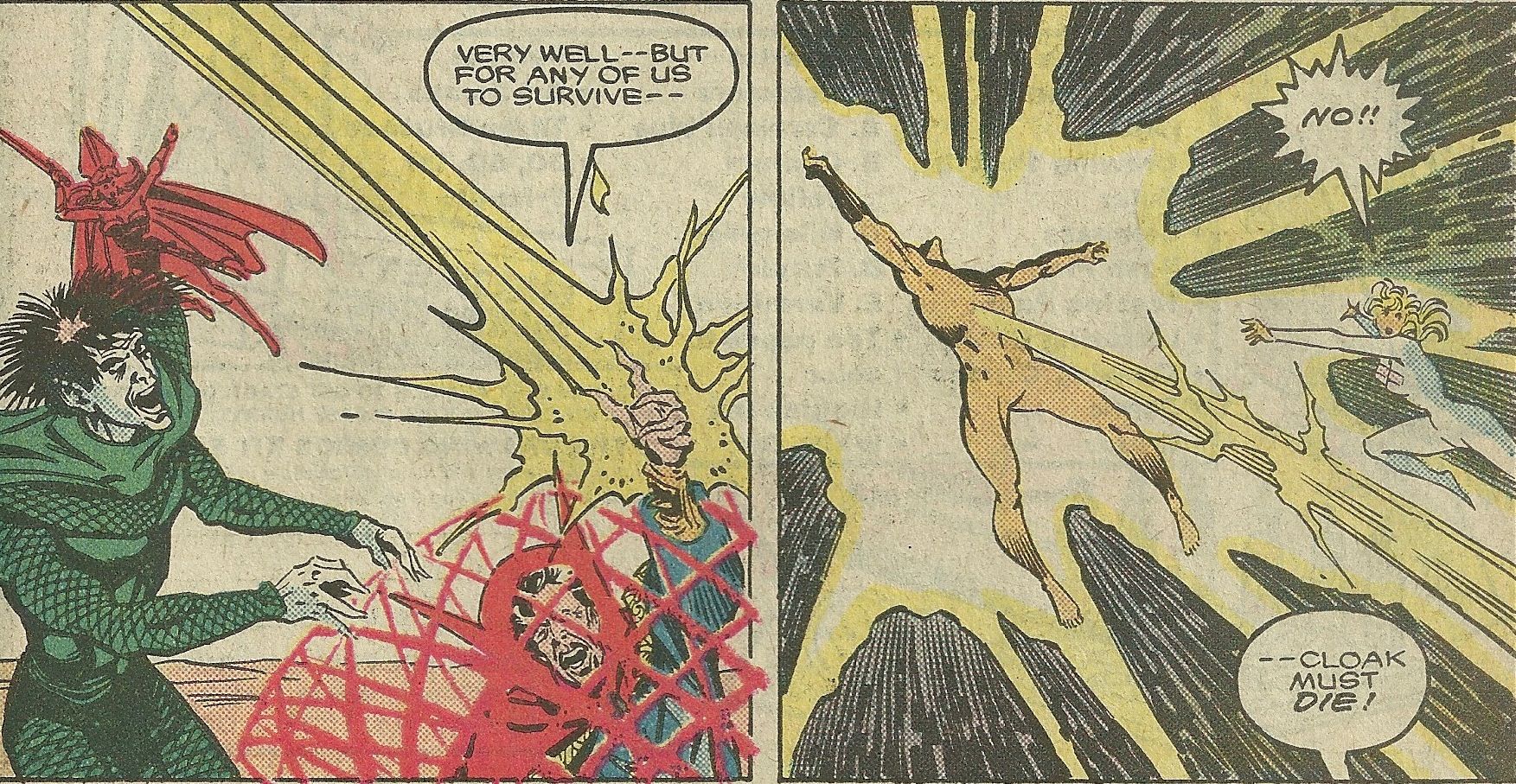

The good guys, as good guys normally do, get their asses kicked for most of the fight, since Nightmare is obviously incredibly powerful on his own turf. In order to beat him, Strange devises a crazy plan whereby he kills Cloak, then yells at Dagger not to try and stop Cloak from being taken to his posthumous "reward" by Valkyrie, but knows Dagger won't listen. By following Cloak into the portal to wherever he's going, presumably Heaven or somewhere similar, Dagger's powers get overcharged. She and Cloak go toward the light, is what I'm saying, and since her powers are light-based, it gives her a boost. This makes her strong enough to take down Nightmare even in his home, and he expels them all in fear and anger, effectively surrendering the fight (and somehow undoing Cloak's death, I guess).

It is Strange's willingness to commit evil acts like murdering an ally that opens the door to saving the day, and his plan that gets the job done. But without Cloak's connection with Dagger, that plan wouldn't have worked, and their bond is in no small part formed through Cloak's focused efforts to keep himself in line and use his powers wisely. She values that in him, and he does it because of her, so the victory against Nightmare comes from an agent of good and an agent of trying-to-be-good supporting and sticking with one another. Yet it also comes from a deliberate betrayal of the worst kind, and a risky manipulation to boot, carried out by a man who knows better but has no other options. You could argue that one or the other of these aspects was more important, but I don't know that Strange Tales evens wants the reader to choose a side. I think the point is that evil is exists in everyone, and no matter what role it plays in our lives, we should be aware of it, mindful of how we use it and how it affects us, and above all respectful of its massive potential influence.