A column in which Matt Derman (Comics Matter) reads & reviews comics from 1987, because that’s the year he was born. Click here for an archive of all the previous posts in the series.

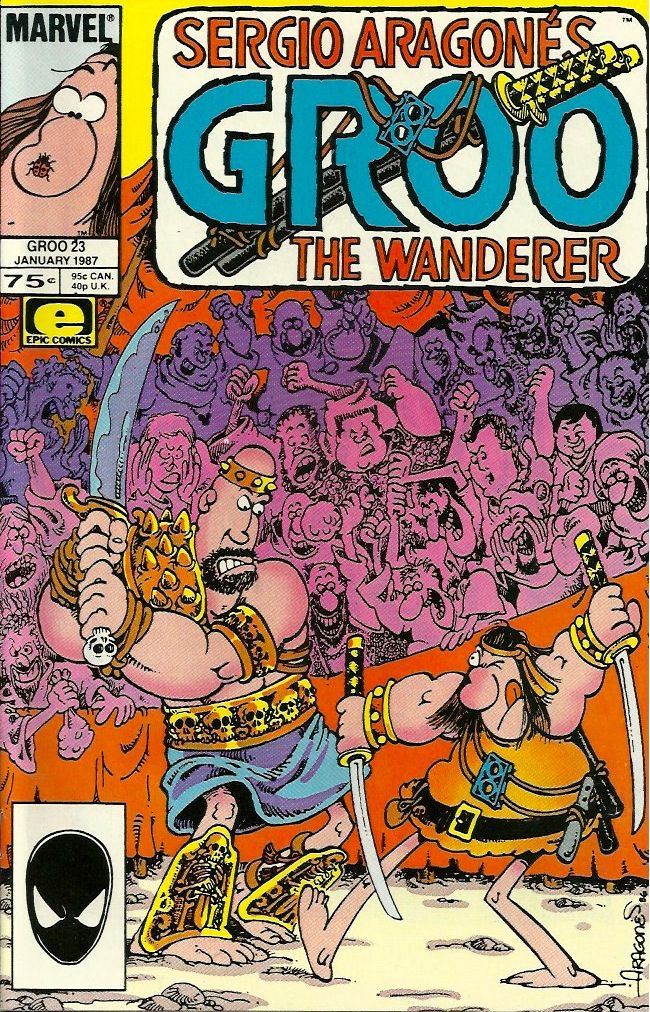

Groo the Wanderer #23-34 (Marvel/Epic) by Sergio Aragonés, Mark Evanier, Tom Luth (#23-32), Janice Cohen (#32-33), Phil DeWalt (#34), Stan Sakai, Jo Duffy (#23-27), Daniel Chichester (#28-34), Steve Buccellato (#32-34)

I'm always interested in the likability of characters in any fiction I consume. I don't necessarily need to like the hero(es), nor do I need to hate the villain(s). In fact, a story with an unsympathetic protagonist that still gets me invested is often that much more enjoyable and engaging, ditto one that has a bad guy with whom I can empathize. For a goofy, lighthearted, action-comedy comicbook, Groo the Wanderer is surprisingly complicated when it comes to the likability of its cast. Just about every character, be they good or bad, major or minor, has an interesting mix of enjoyable and off-putting qualities. There's a general silliness to everyone that makes them all fun to spend time with, but most of them are also selfish, judgmental, dishonest, and/or violent. It's a collection of largely terrible people, behaving in wonderfully entertaining ways, and most of the time they get what's coming to them in the end, so that there's a nice narrative satisfaction when each issue resolves. On top of all that, everything is done in an art style that's equal parts ridiculous and dense, so that what feel like simple stories are often deceptively more involved than they appear at first glance.

Title character Groo isn't really on the side of good or evil, he's just on the side of Groo. He's an impossibly skilled warrior who's also remarkably dim-witted and oblivious, traveling from place to place in search of employment, adventure, or any other excuse to use his destructive combat talents. He'll kill just about anyone for any reason, and while many of his victims deserve it, just as many do not. He has a reputation throughout the world for being dangerous, short-tempered, and incredibly deadly, all of which is true, and those are the most negative aspects of Groo, the parts that could, in theory, make him hard to root for. But Groo is also too stupid to be anything but totally honest and earnest at all times. He's a mindless killer, yes, but not a malicious one, he simply enjoys fighting and knows he's good at it, so he does it whenever he can, needing only the flimsiest excuse to slay everyone he sees. On the one hand, that's horrible behavior, but it's hard to hold it against him when he's so wide-eyed and equal-opportunity about it. His idiocy and openness endear him to the reader, so that even if we don't always approve of who he kills or why, we still forgive him for it, and quite quickly at that. Besides which, it's not at all uncommon for Groo to be murdering the forces of evil, doing good and saving innocent lives even if it's not his goal and he doesn't realize that's what he's doing. He's not exactly a hero, but he's much closer to hero than villain, a lovable if unpredictable oaf.

There are plenty of characters in this series who are more concretely established as bad guys, including but not limited to witches Arba and Dakarba, con man Pal and his Groo-esque partner Drumm, and bandit leader Taranto. These are all people who try to take advantage of Groo through various methods in order to advance their own power, using him as a tool to dole out violence in ways they cannot so that they might benefit from the consequences. While there's nothing redeemable about these characters in and of themselves, they always end up getting pretty much the exact opposite of what they're after, because while Groo is foolish and trusting enough to be easily manipulated by them, he's also too unaware and unfocused not to screw up whatever it is he's supposed to be doing for them. He regularly misinterprets circumstances, blurts out of secrets, and/or flies off the handle into bloodthirsty rages, so that he botches whatever mission he's been unknowingly sent on by these more malevolent figures, even as he genuinely tries to do whatever they've asked of him. Full-fledged villains though they may be, it's always fun to see these characters show up, because watching them get their just desserts is as gratifying as it is amusing. Sinister schemes never pay off in Groo the Wanderer, while straightforward killing often does.

There aren't many (if any) truly good characters around, but there are a few neutral observer types, like the Minstrel and Sage, who balance the scales at least to some degree. They, like Groo, have no specific ambitions, but unlike Groo they want to live their lives as peacefully as possible. This does sometimes mean tricking Groo, but more to get away from him than to use him to serve their own interests. And these are the people who Groo will sometimes accidentally assist, saving them from more wicked characters without meaning to or even understanding what's happening. The everyday, nameless citizens of the various towns and villages Groo passes through tend to be in this category as well, normal folks who are just trying to get by and who only dislike Groo because they know that wherever he goes, devastation tends to follow. It does happen that Groo wrecks whole cities and ruins the lives of these people, but usually that's a consequence of them in some way trying to control him in an attempt to avoid that very outcome. So just like the evildoers of this world, when average townspeople attempt to manipulate Groo, it ends poorly for them. I suppose the underlying lesson in this is that no one, no matter how simpleminded and/or potentially dangerous, should be lied to by others or fooled into doing something they otherwise would not. Even the Groos of the world deserve forthrightness and respect, at least according to this comic, and it's not a bad point to make. With no one being wholly good, there's an argument to be made that Groo is not inherently worse than anyone else, and therefore shouldn't be treated differently just because of his violent streak. I'm not sure I agree with that when it comes to applying it to our own reality, but it is at least interesting to consider, and within the context of this title, it's a consistent truth.

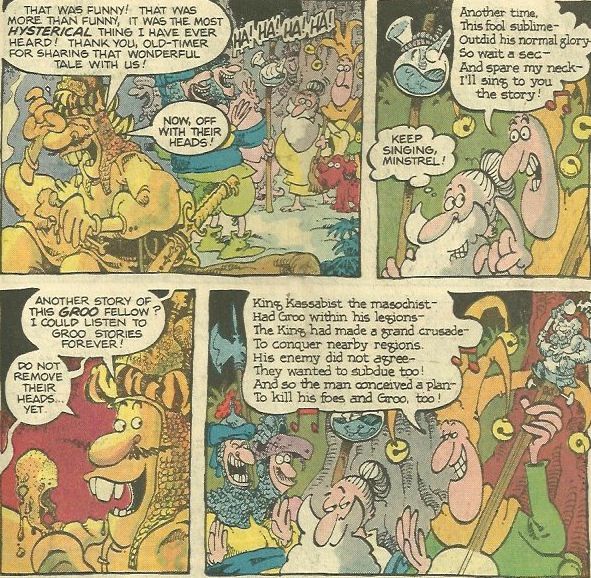

And make no mistake, Groo the Wanderer is happy to impart these kinds of lessons to its audience. Every issue ends with a plainly stated and clearly labeled moral, things like, "Putting beauty before brains is the surest way to wind up with neither," or "When you deal in weapons, there are no winners...only losers," or my persona favorite, "Everyone is somebody's hero." Not all of these morals are equally convincing or compelling ("The way to a man's heart is through his stomach--a route which takes you nowhere near his brain" stands out as perhaps the weakest and most pointless of the bunch) but it's nice that a comicbook which, on the surface, appears to be just a string of gags tied together through a buffoon of a leading man, is quietly trying to be more than that, to impart some actual wisdom and say something with real meaning in the end. It doesn't always work, and neither do the many, many jokes along the way, but the effort is always there, and that counts for a lot.

Sergio Aragonés plots and draws all of these issues, with Mark Evanier filling in the actual scripts, and there's clearly a lot of love, passion, and energy coming from both of those creators. Aragonés' style is broad and cartoony, but also impressively full and detailed. When he draws a crowd, he gives ever member of it their own appearance and expression. When he draws a town, each building looks different, and each place as a whole stands out from the rest. There are similarities between one location and the next, but none of them are identical and nothing is rushed, even in the most insignificant backgrounds. The art can at times feel a little busy, but Aragonés lays everything out so that the focus of each panel is immediately evident and nothing is ever unclear. Some of the stories cover a lot of ground and involve many different players in the span of a single issue, but the reader is never lost or left behind, even when Groo is. And every issue is its own whole story, even if the narrative continues into another issue. So, for instance, we get the complete tale of how Groo gets his dog Rufferto in issue #29, and then we see how he keeps Rufferto from others who would claim him as their own in issue #30. This could be seen as a two-part arc, and in many ways it is, with the same characters and storylines carrying over from on issue to the next. But each chapter is its own thing, too, enjoyable and understandable without the other half. Much of this can be attributed to Aragonés' full-bodied artwork, reliably packing in a lot of story into every 22-page installment.

Evanier does a lot of that work, too, writing strong expositional dialogue and trimming the fat in his scripts whenever he can so the core of the story is what remains. This is not to say he doesn't ever indulge in flourishes. On the contrary, in addition to each issue ending with a moral, they all open with a little introductory poem, and Evanier uses different rhyme schemes and rhythmic patterns for these so that, while they're always expected, they don't grow repetitive or dull. There are, unfortunately, some running gags which don't hold up as well or for as long, things like one character saying, "As any fool can plainly see," and Groo immediately responding, "I can plainly see that." It's funny, and the fact that it happens multiple times is amusing in its own right, but after the first few you start to anticipate them and they lose their impact. To combat this, Evanier fits in as many jokes as he can in the words themselves, and Aragonés does the same with each new plot and all the visuals. So there's humor coming from every angle on every page, meaning even if any individual joke fails to connect, there's always another one waiting right next to it that can pick up the slack. That's a big part of the appeal of this title, and it's also why some of the less desirable pieces of Groo as a protagonist aren't as detrimental as they might otherwise be. There's just too damn much fun to be had in this book to get hung up on the main character's morality in any significant way.

Most of the coloring in this run is handled by Tom Luth, although part of issue #32 and all of #33 is colored by Janice Cohen, with #34 by Paul DeWalt. Regardless of who is in charge of the colors, though, they're always a big part of making Aragonés' overstuffed art succeed. I mentioned above that Aragonés is good at targeting the reader's attention to the right spot in any given image, but the coloring does that, too, with the less important pieces often done in only one or two hues while the central action is colored in full detail. There's so much to color in Aragonés' drawings, from the jam-packed two-page spreads featured on pages 2-3 of every issue, to the full-scale war scenes as Groo slices his way through both sides of a conflict, to the well-populated towns that Groo visits on his many adventures. New characters, settings, costumes, and more are included every issue, and it all needs to be colored in a way that doesn't dull or muddy the tiny bits and pieces Aragonés has taken the time to include in his linework. Luth, Cohen, and DeWalt all obviously understand the importance of careful coloring on a book like this, and they do it justice every time. It's as huge a component of the series as any, because for any one thing to work on a book as finely crafted and complex as this, everything else needs to work, too.

Groo the Wanderer isn't a difficult read; it's not a challenge or a lofty, esoteric, or experimental comic. It's as upfront a series as it's title character is a person, unambiguously shooting for easy laughs, the blunt delivery of everyday life lessons, and widespread fictional mayhem. But a book can be direct without being simple, and that's exactly what you get here. Groo the Wanderer has characters that you love and hate at the same time with equal enthusiasm, it's absurd and meaningful at once, it provides both purely fun and legitimately thought-provoking material. It is no more or less than it's trying to be, but the people who make it clearly do so out of love, a project they take seriously and also enjoy the hell out of. The reader is invited to do the same, to revel in the comedy but to really consider the philosophy, too, however lightweight it may be. It can be rewarding even if you only do one or the other, but it is greater than the sum of its parts, a title that doesn't always have a lot to say, but always says it as completely and loudly as it can.