A column in which Matt Derman (Comics Matter) reads & reviews comics from 1987, because that’s the year he was born. Click here for an archive of all the previous posts in the series.

Captain America #325-336 (Marvel) by Mark Gruenwald, Paul Neary (#325-329, 331), Tom Morgan (#330, 332-336), John Beatty (#325-327), Kent Williams (#326), Vince Colletta (#328-329, 331), Sam de la Rosa (#330), Bob McLeod (#332), Dave Hunt (#333-336), Ken Feduniewicz (#325-330, 332-334), Bob Sharen (#331, 335-336), Diana Albers (#325-332), Bill Oakley (#333), Ken Lopez (#333-334), Jack Morelli (#335-336), Don Daley (#325-334), Ralph Macchio (#335-336)

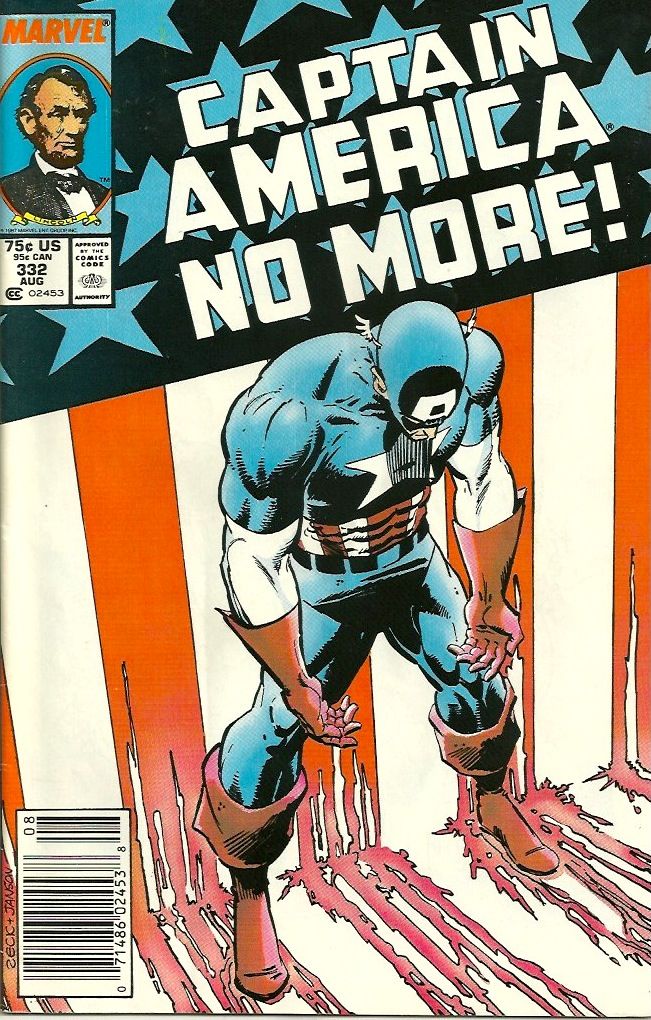

In some respects, this is a tricky run of issues to review, because they include the beginning but not the ending of the "Captain America No More" saga in which Steve Rogers turned in his shield, his costume, and the moniker that comes with them, and John Walker was appointed to replace him. Rogers' retirement occurs in issue #332, and Walker becomes Captain America in #333, so while there are a few issues from 1987 exploring that new status quo, the resolution wouldn't come until February 1989's Captain America #350. In that sense, then, the issues I'm covering here represent something incomplete, the start of an epic storyline that doesn't yet finish. But there is still plenty to discuss in terms of what these issues have in common, and how they lead up to and deliver the rather bold, shocking, and powerful moment of Rogers' decision to give up his Captain America persona. This is a comicbook about the downside of idealism, the strain that any rigid belief system puts on those who follow it, as well as the dangers and evils which that kind of extreme thinking can engender. It's not necessarily a cautionary tale, but it does warn against believing in anything too intensely or blindly, and shows the readers and characters alike how impractical and unpleasant it can be to try and live life according to a strict set of rules. The world is not rigid or simple enough for any idealism to be a perfect fit, and that's a lesson learned many times in many ways over the course of these issues.

Even before he retires as Captain America, we see Rogers struggle against and because of his morality. He very nearly gets blown up and then just-as-nearly drowns while trying to save criminal kingpin the Slug from a sinking ship. It is Rogers' former partner Nomad who sets the ship ablaze in the first place, and were it up to Nomad, the Slug would've died in the wreckage. But Rogers is too committed to saving lives and upholding the law to merely abandon the Slug to such an awful fate, so he does everything in his power to protect the villain, even when it means risking his own safety. One issue later, Rogers is confronted by the "ghosts" of several enemies he'd previously killed (or at least watched die)—M.O.D.O.K., the Porcupine, Red Skull, and a member of terrorist group Ultimatum who Rogers shot to death not long before. While fighting these apparitions, Rogers constantly questions what they are, finding it hard to believe they're truly the risen spirits of his old foes. If they really are ghosts, or robots designed to look like villains, or any similarly non-human entities, Rogers would feel more comfortable fighting them with all his might, less afraid of the potentially fatal consequences of cutting loose. But to him they move and feel like actual human beings (really they're drug-induced hallucinations) so he holds back a little, not wanting to do more harm than necessary or kill any more people than he already has. Even when fighting the supposedly already-dead, Rogers' morals prove to be something of an obstacle, causing him to hold back in a fight where he's wildly outnumbered and overpowered, and all of his opponents are coming at him full force.

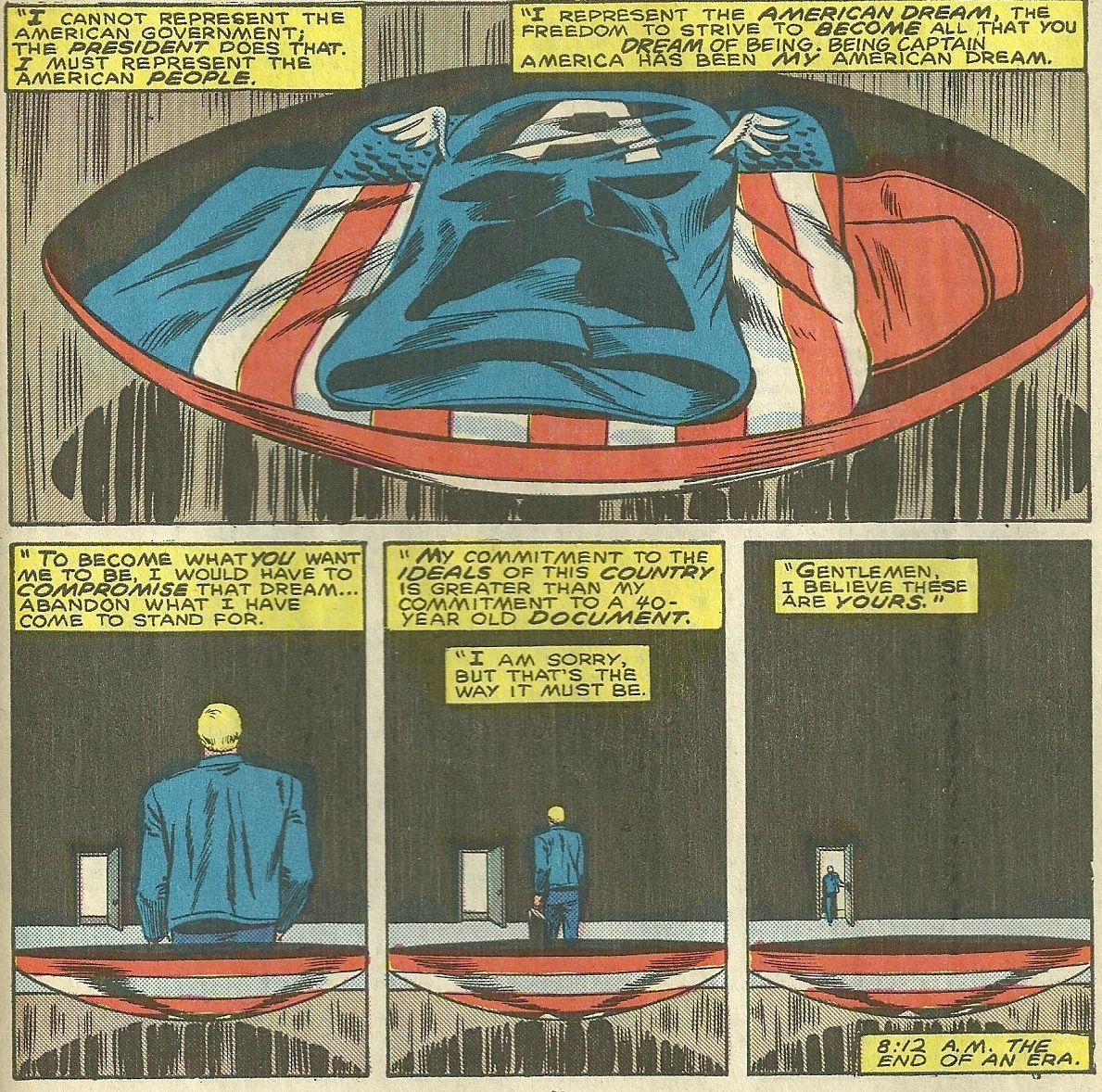

To be fair, it is not so much his morality as his sense of independence and duty that ultimately drives Rogers to walk away from the Captain America role. But it's all tied together, all part of the same unbending life philosophy under which Rogers operates, both in-costume and out. His avoidance of lethal force and his insistence on being his own master are connected, two small pieces of his larger core goodness. Just as he doesn't want to kill when he can merely defeat and detain, he doesn't want to

represent the American government when he can instead represent the American dream, or his take on the American dream, at any rate. Trouble is, the rest of the world isn't designed to accommodate that attitude, and Rogers finds himself forced to choose between being Captain America and being the hero he wants to be. A presidential commission is put together to regulate the activities of superhumans, and one of their first orders of business is to try and make Captain America into a full-fledged government employee once again, a soldier following orders rather than a vigilante fighting whatever battles he deems worthy. As much as he loves being Captain America, Rogers cannot quite come to terms with the idea of giving up his freedom; to him, Captain America is bigger than the nation's political system, as are the causes he fights for, the ideas which he symbolizes. Being Captain America the soldier isn't as pure or as good in Rogers' mind as being Captain America the superhero, but since the U.S. government technically owns the Captain America name and concept, Rogers doesn't really have much say in the matter. His only options are to play along with the Commission's desires or stop being Captain America at all, and he chooses the latter, more concerned with preserving his ideals than his identity.

The Commission is surprised by Rogers' decision, even upset by it, but they don't let it stop them or even significantly slow them down. They set to work right away looking for a new Captain America, and quickly find him in John Walker, a.k.a. Super-Patriot. Walker is an idealist, too, but his beliefs don't line up with Rogers'. In fact, they're nearly perfect opposites, at least when it comes to the Commission and Captain America. For Walker, patriotism and loyalty to the government are essentially one and the same; unlike Rogers, he sees no difference between America as a political entity and America as an idea. So when the Commission offers to make him Captain America, Walker accepts readily, to the point that he compromises several other beliefs he holds dear in the name of serving his country.

As Super-Patriot, Walker was just as focused on his P.R. as he was on actually doing good. He even had a manager, Ethan Thurm, and the two of them really created the Super-Patriot brand together, Thurm seeing Walker's enhanced strength and heroic aspirations as a great opportunity for some fame and fortune. Even though their priorities were not 100% the same, overall Walker and Thurm worked well together and formed a kind of professional friendship. Walker felt somewhat indebted to Thurm for discovering him and making him into Super-Patriot in the first place, and Thurm was grateful to have a client as hard-working, determined, and successful as Walker. However, once the Commission showed up with its offer, they also demanded that Thurm be removed from the picture, not wanting to work with or employ someone with as questionable a character or as sketchy a background as his. Walker accepted the Commission's terms almost immediately, turning his former manager and friend into an enemy overnight. Along the same lines, Super-Patriot worked with a trio of sidekicks called the Buckies, three relatively unintelligent but physically fit men who were wholehearted followers of Walker. The Commission also insisted that two of the Buckies be dropped due to their own criminal histories, and Walker went right along with that as well. After spending a considerable amount of time and effort building up Super-Patriot's reputation, Walker, Thurm, and the Buckies had become a pretty tight unit, readily trusting and relying on one another. As soon as his country asked him to dismantle that team, though, Walker agreed, demonstrating the true depths of his devotion to America.

Walker's eagerness to play the part of the obedient soldier doesn't end up being all it's cracked up to be, as sticking to his excessively patriotic outlook starts to take its toll early on. On his first field assignment, he gets sent back to the area where he grew up, and is asked to infiltrate and take down an organization whose beliefs he mostly agrees with, and whose members include friends from his past. The group, who call themselves the Watchdogs, are self-assigned morality police, blowing up buildings and killing people in the name of what they consider the public good. Most of what we see them do is anti-smut, destroying an adult bookstore, storming a library, and attempting to hang a man they think is a pornographer, but is really Walker's partner, Lemar/Bucky (the only one of the Buckies deemed fit for service by the Commission). Walker is sympathetic to the Watchdogs' cause, and most of their rhetoric appeals to him. It's only their methos he has a problem with, but even that is at least partly due to the fact that the government told him he had to have a problem with them.

Meanwhile, the difficulty of having his first mission be in his hometown and seeing his partner's life threatened starts to make Walker wonder if it was a set-up, if the Commission intentionally sent him into a situation designed to measure his commitment. Even with that suspicion, he completes his mission dutifully, but he begins to lose trust in his new bosses, and asks himself if that might have been Rogers' reason for leaving. Walker wants to be the best Captain America he can be, and to him that means following the orders his country gives him, no matter what. That attitude is what gets him the gig, but then it also challenges him right away, making him fight people he understands, agrees with, and even, in some cases, personally likes. He does it because that's the job, and he believes in the job, but that belief gets a little rattled when put to the test.

As a group, the Watchdogs are probably the strongest single warning against idealistic/extremist thinking these issues of Captain America have to offer. They're terrorists, militant and well-armed and totally out of control, holding themselves so far above the law or any semblance of civilized society it's a wonder they can even maintain their normal lives and day jobs. They kill and destroy casually and with great enthusiasm, all the while thinking themselves righteous defenders of decency. While the Watchdogs are the worst, there are lots of characters, good, bad, and in between, who serve as examples of the dangers of being too narrow-minded or immovable. I mentioned above how Nomad set the Slug's boat on fire, causing several deaths and putting plenty more lives at risk. He spends a few weeks on the boat before making his move, watching the debauchery and depravity that runs rampant on a pleasure yacht owned by a major crime boss, and decides that nobody on the ship is worth saving. Nomad is so fiercely devoted to battling evil that he loses any sense of mercy or empathy, and sees anyone even tangentially connected to evil-doings, anyone who so much as watches them occur without protesting, as deserving to die, or at least not deserving of the energy it would take to keep them alive.

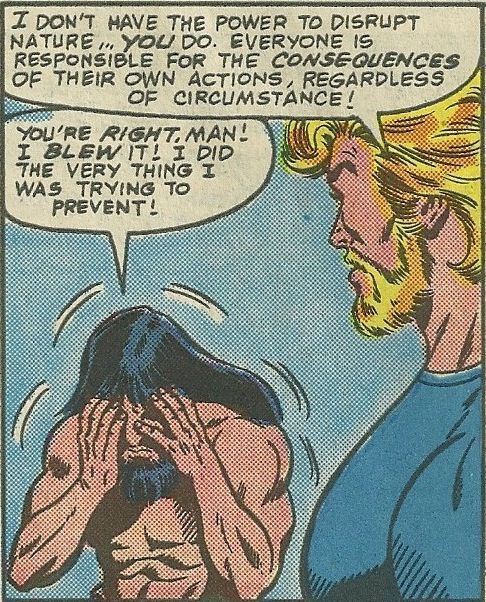

Brother Nature, who can control the forces of nature and tries to defend the forest from the logging industry, ends up letting his powers run wild, doing more harm than good. Warhead, another character who considers himself a patriot, threatens to set off a nuke in Washington, D.C. if America doesn't declare war on somebody—anybody—by the end of the day. Whatever the intentions or self-perceptions of the people involved, time and again Captain America shows us how any hard-and-fast dogma can and likely will cause trouble, from something as small as Walker's highly increased stress to Warhead falling off the top of the Washington Monument and blowing himself up with a grenade mid-air.

There's even an exception present to prove the rule. Demolition Man (D-Man for short) is a professional wrestler named Dennis Dunphy who Rogers runs into on a fact-finding mission, prompting Dunphy to sort of half-randomly decide to be a superhero, too. He makes himself a costume, picks a codename inspired by his wrestler name, and casually, almost effortlessly, turns himself into a superhero. It's kind of awesome to watch, and D-Man is a welcome breath of fresh air, because he has none of the heaviness or rigidity of the other characters. He's so happy just to be in the superhero game, he doesn't really get wrapped up in having a cause beyond that. From the very beginning, he's just a nice guy who wants to help out, and his relative lack of problems stems from this equal lack of severity.

I don't think the message of Captain America is that we should all be ready to compromise or give up our beliefs for the sake of having it easy. On the contrary, Rogers is very much played as an admirable, noble, fully heroic figure when he turns the Commission down, a man who understands the importance and purpose of Captain America better than anyone else ever could, and therefore refuses to take part in diluting or warping that purpose. Walker, for his part, is sympathetic if not wholly likable, a somewhat misguided guy who legitimately wants to live up to and even surpass the impressive legacy that Rogers has established. Both of the characters who spend time in the title role steadfastly stick to their guns, and both of them win the reader over because of it, but neither of them do so without cost. If anything, that's the main takeaway from these issues: always hang onto the ideals that matter most, but expect and be prepared to take your lumps when you do. On top of that, of course, is the lesson of what can happen if we let our ideals run amok, leading to the chaos and devastation that is always the result of true extremism. Captain America is an endorsement for balance, for finding the sweet spot where we can stand by our convictions without needing to violently force them on others.