Dungeons & Dragons, the first commercially-available roleplay game, was created by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson and published in 1974. The fantasy game, which encourages free play and imagination, pulled elements from strategic war games and the work of J.R.R. Tolkien to allow players to run campaigns as magical characters. Despite its mostly positive intentions, paranoia around Satanism and witchcraft created a public panic about D&D that lasted throughout the '80s and part of the '90s. Of course, the fear surrounding the game only increased its popularity.

The '60s and '70s were a time of spiritual exploration that popularized two fringe religions: Wicca and Satanism, both of which worried Christian America. The '70s were also marred by a series of high profile murders and serial killings that were loosely connected to supernatural cults and rumored to have been influenced by the devil itself.

At the same time, politically-minded, right-wing Christians organized to defend what they considered proper values, following two key Civil Rights rulings: public school desegregation in 1970 and Roe v. Wade in 1973. By the '80s, there were a TV and radio in every house with a televangelical preacher on the local station.

Due to a series of tragic suicides and increasing fervor about D&D's exploration of magic and mysticism, the game became a focal point for people who feared Satanism was corrupting their children.

James Dallas Egbert III & Irving Pulling

For approximately five years, D&D was a word-of-mouth phenomenon among students. This ended in 1979, when 16 year-old James Dallas Egbert III disappeared in the steam tunnels of his school, where he and his friends often went to play D&D. His family hired private investigator Michael Dear, who theorized that Egbert's involvement in the game contributed to his disappearance.

The press published Dear's theory and when Egbert committed suicide in 1980 -- successfully completing his third attempt -- Dungeons & Dragons took the blame. The book Mazes and Monsters (1981) and the 1982 film adaptation, starring Tom Hanks, made the case famous. Dear later clarified -- in his 1984 book The Dungeon Master -- that he had never believed the game had anything to do with Egbert's suicide, which he linked to his chronic depression and family issues. Unfortunately, by then, it was too late.

In 1982, Irving Pulling, a kid who played in a school-supervised D&D campaign, committed suicide. His mother, Patricia Pulling, sued the school director and TSR, the game's publishers at the time, alleging that her son died because "he had received a curse during a game session."

The case was eventually thrown out of court in 1984, but it fanned the flames of D&D's supposedly Satanic subtext, while at the same time bringing publicity to the game and boosting its sales. Patricia Pulling also funded BADD (Bothered About Dungeons and Dragons) to accuse D&D of encouraging Satanism, rape and suicide. Dungeon & Dragons sales soared.

Satanic Panic

Throughout the '80s, multiple books and films painted D&D as morally corrupt and media attention continued to frame the game in the same way. In 1985, 60 Minutes dedicated a full hour to the supposed connection between D&D, Satanic rites, murders and suicides and in 1987, Peter Leithart and George Grant published The Catechism of the New Age, a pamphlet where they introduced the idea that D&D was immoral because roleplaying allowed too much freedom for critical thinking, which might lead to heretical ideas. They also argued the Moral Alignment system was inherently evil.

With so much focus on the game's apparent corruptive tendencies, parents forced their kids to burn game manuals and figurines -- but sales continued to soar. Meanwhile, other figures began to argue in the game's favor.

In his 1987 book Role-Playing Mastery, D&D co-creator Gary Gygax said it was ahistorical for critics "to attribute war, killing, and violence to film, TV, and role-playing games." A year later, Ravenloft and Dragonlance author Tracey Hickman, who is also a devout Mormon, published an essay encouraging D&D players to communicate with their parents and pastors and to invite them to participate in the game, so they could see there was nothing wrong with it. The essay was well-received, but unfortunately, there was another high-profile killing later that year.

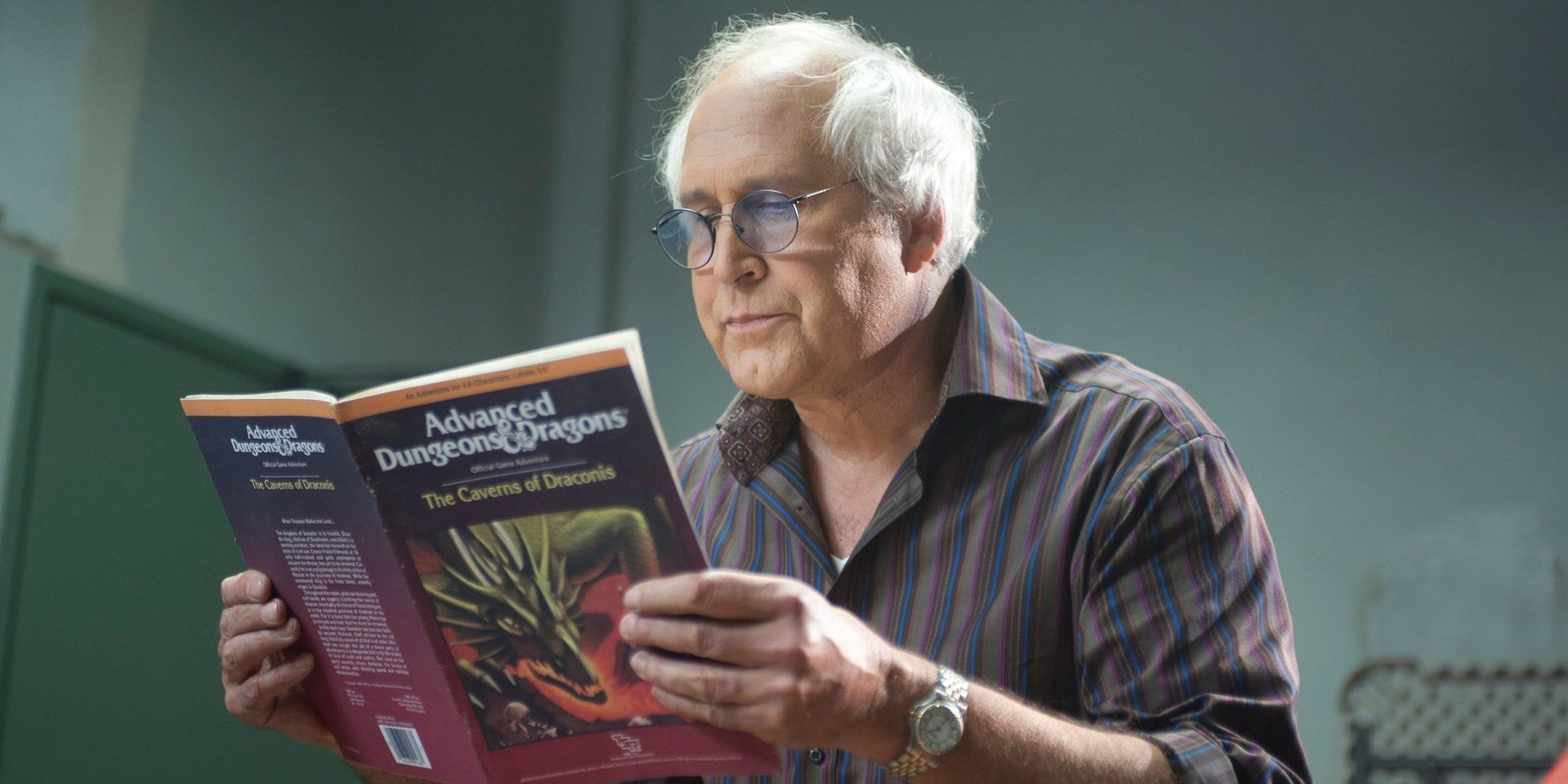

After Chris Pritchard and two friends conspired to murder Pritchard's stepfather in his sleep, the media ignored the obvious financial motivation and instead focused on the men being in the same D&D group. Two books were inspired by the case, both of which emphasized this connection as well. While the case was ongoing, TSR released Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition, which replaced the word "demon" with terms like tanar'ri and baatezu, possibly in response to moral panic about the game.

Wizards of the Coast

The '90s marked the beginning of the end of the Satanic Panic and also a slight decline in D&D's popularity. In 1997, two things happened: Patricia Pulling's death disbanded BADD and TSR sold Dungeons & Dragons to Wizards of the Coast. WotC brought D&D back to profitable life, even releasing the cheekily named Guide to Hell in 1999.

Although the game inspired moral panic after it was introduced, it has since become a tool for education and therapy, as well as a popular past time for people from all backgrounds. Even horror RPGs inspired by D&D like Call of Cthulhu (1981) and Vampire: The Masquerade (1991) are almost free of Satanic stigma. The moral police have moved onto video games and fan fiction.

The Satanic Panic actually seems so irrelevant that even Stranger Things, the apotheosis of '80s geeky nostalgia -- which opens with an intense D&D scene and even has its own, purchasable D&D guide for fans -- didn't even mention it.