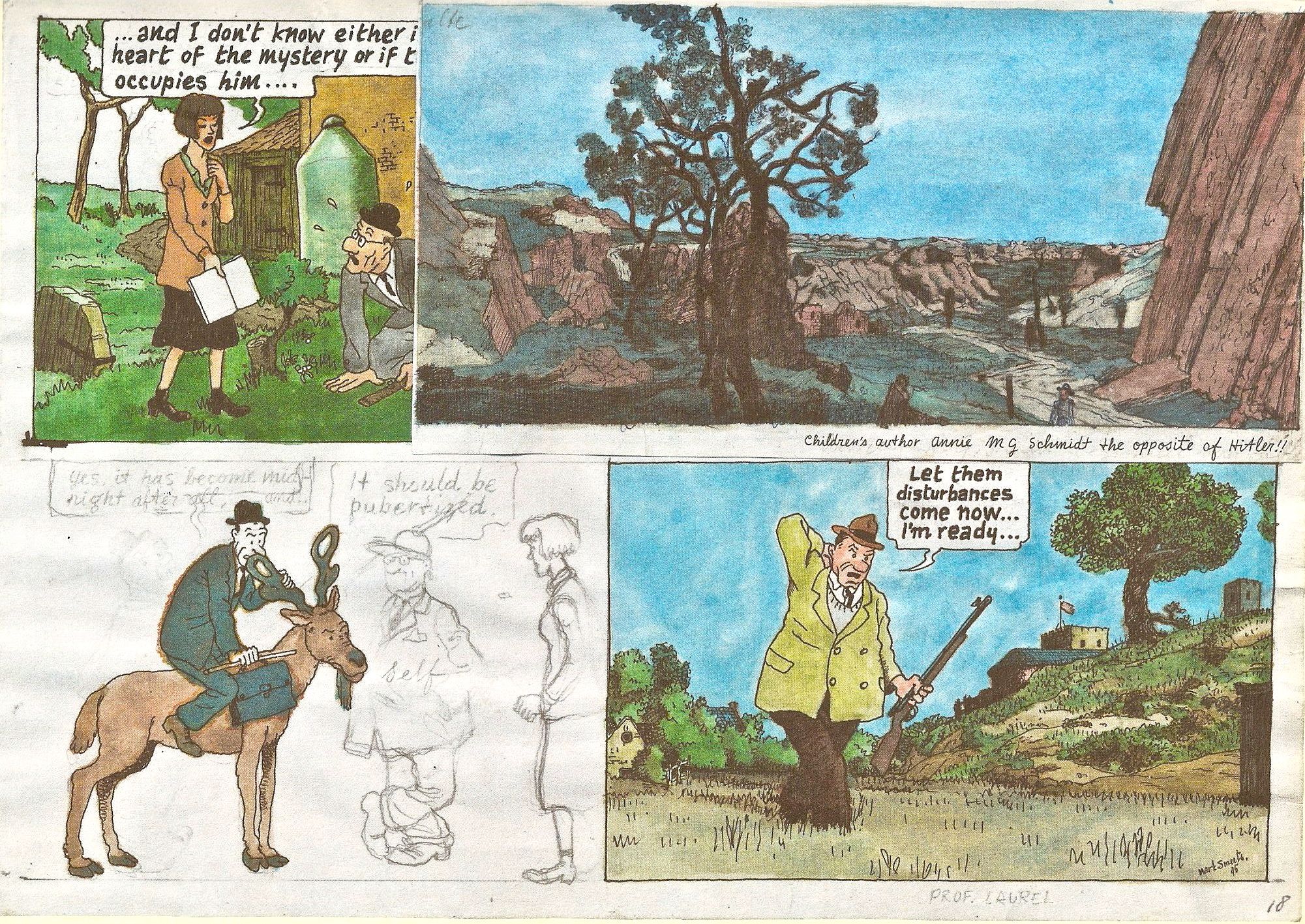

Kramers Ergot 6 (2006), page 35 panels 1-4. Marc Smeets.

Sequence is vast. As I've said here a few times before, it's what's makes comics comics. If it's got images placed in sequence on the page or on the screen and it wants to call itself comics, then I for one fail to see grounds for rejecting it as such. That's not to say that all comics are equal -- though sequence is what creates visual art as comics, the skill of its use is a major part of what creates good or bad ones. But the idea that certain kinds of sequencing are more appropriate to comics, or even work better in comics than others is simply a fallacy. The old chestnut "it's the singer, not the song" applies here. A method of sequencing's effectiveness is directly proportionate to the skill and consideration of the artist using it.

The biggest misconception about sequence in comics is that it's strictly a storytelling tool. It's not. Sequence is simply the overriding device that comics use to deliver whatever it is they're delivering. One might just as well claim that the screen a film is projected onto or the pages of a printed book have some inherent connection to creating narrative. No, sequencing extends beyond all storytelling possibilities to encompass more. It is the comics medium's vehicle. If narrative is what an artist intends they'll almost certainly use sequence to propel it, to take the reader from one to ten via two, three, four, et cetera. But if an artist is focused on doing something else with the comics form -- creating abstraction, presenting snapshots too brief to be called "story", showing off various images in harmonious arrangement, or any one of a million other options -- sequence will more than likely be the driving force as well. The only thing sequencing always creates is comics. And comics can be anything.

All this being said, storytelling is still far and away the most common use comics artists find for sequencing, and as such it's probably also the potentiality of comics that's seen the most elegant uses of sequence. By comparison, the sequencing seen in most abstract or non-narrative comics is relatively basic. The little-seen work of the late Dutch cartoonist Marc Smeets, however, proves a brilliant exception to that rule.

Even the best-versed of English language comics readers won't have seen many Smeets pages. Chris Ware presented a handful late last decade -- a few translated, relettered pages in Kramers Ergot and a few original Dutch language ones in The Ganzfeld. It's tough to draw any meaningful conclusions about Smeets as an artist from such a small smattering of work, but based on a few testimonials in the Ware text piece that prefaces the Kramers passage the page above is taken from (not to mention the work itself), Smeets wasn't too much concerned with creating comprehensible, linear storytelling. Rather, actively making nonsense seems to have been his priority. Smeets' pages belong more to the whimsical, evasive tradition of Lewis Carroll, free jazz, and Dadaism than the more direct literary and artistic traditions most comics strive for a place in. His panels display not even the barest hint of a narrative connection to one another, image after image appearing abruptly, with no explanation given as to why this one comes next. Rather than clarify things, the word balloons only obfuscate further, non sequitur snippets of text likely as not cut off midstream by panel borders or left uninked and barely visible.

Smeets' sequencing is truer to abstract artistic goals than the time-honored comics maxim of "serve the story". With no story available to be served, a kind of delicate, asymmetrical self-expression takes control, everything proceeding from a mysterious internal logic (or illogic) instead of a dictated set of plot points. The first panel presents an elliptical snatch of what could be a story about anything in a deeply gorgeous, watercolored take on the familiar Herge style. But even that brief fragment of information is fragmented further, interrupted by a panel border that allows the landscape in the next panel to stretch out to properly roomy proportions. It's key to note that the landscape isn't drawn over the edge of the previous panel; this isn't comics as collage. Smeets simply goes further than most in letting the pictures dictate the flow of his pages. If a few words are cut off to accommodate a picture's achieving its full potential, well, they aren't saying much of great importance to begin with. What's far more important is seeing Smeets' wistful, assured and yet almost hesitant images as he imagines them.

From a snippet of what looks like it could be a story, to a completely pictorial, story-free panel, we proceed next to a panel featuring the same characters as the first. It's anything but a linear progression, though -- the main focus of the panel is its only inked and colored elements, the suited man and the deer he rides in on. The characters seen previously are only penciled, the familiarity they bring (and narrative progression that familiarity implies) left purposely faint, indistinct. The same is true with the words, which here again are simply not given as much importance as the pictures' own logic, here a deadpan absurdism that sees the reindeer rider apparently smelling his mount's antlers. And then another completely disconnected image cuts in, a hunter walking brusquely through a new and different landscape in search of some vague "disturbances". That's the sum total of what we're given, aside from a scribbled note in the middle gutter declaring that Dutch children's author Annie M.G. Schmidt is the opposite of Hitler.

Smeets' page is an example of what comics can do cut free from story, a triumph of pictorial over narrative logic. Though they have only the barest of connections (a shared drawing style; the re-occurrence, albeit in ghostly penciled form, of characters), these images are undeniably linked by their shared tone, a quiet, pastoral, deeply strange aura of nostalgic whimsy. This sequence hangs together just as well as any Jack Kirby fight or Jaime Hernandez conversation, but what unifies it isn't the continuity between its panels. It's the discontinuity, the rhythmic leaps of imagination it forces its readers into between each two frames. It's possible to see this method of sequencing as comics asking much of the reader and failing to deliver any reward; but it would be much truer to say that it asks nothing at all, presents what it wishes to, and leaves readers with an odd, ineffable beauty that stands on its own merits.