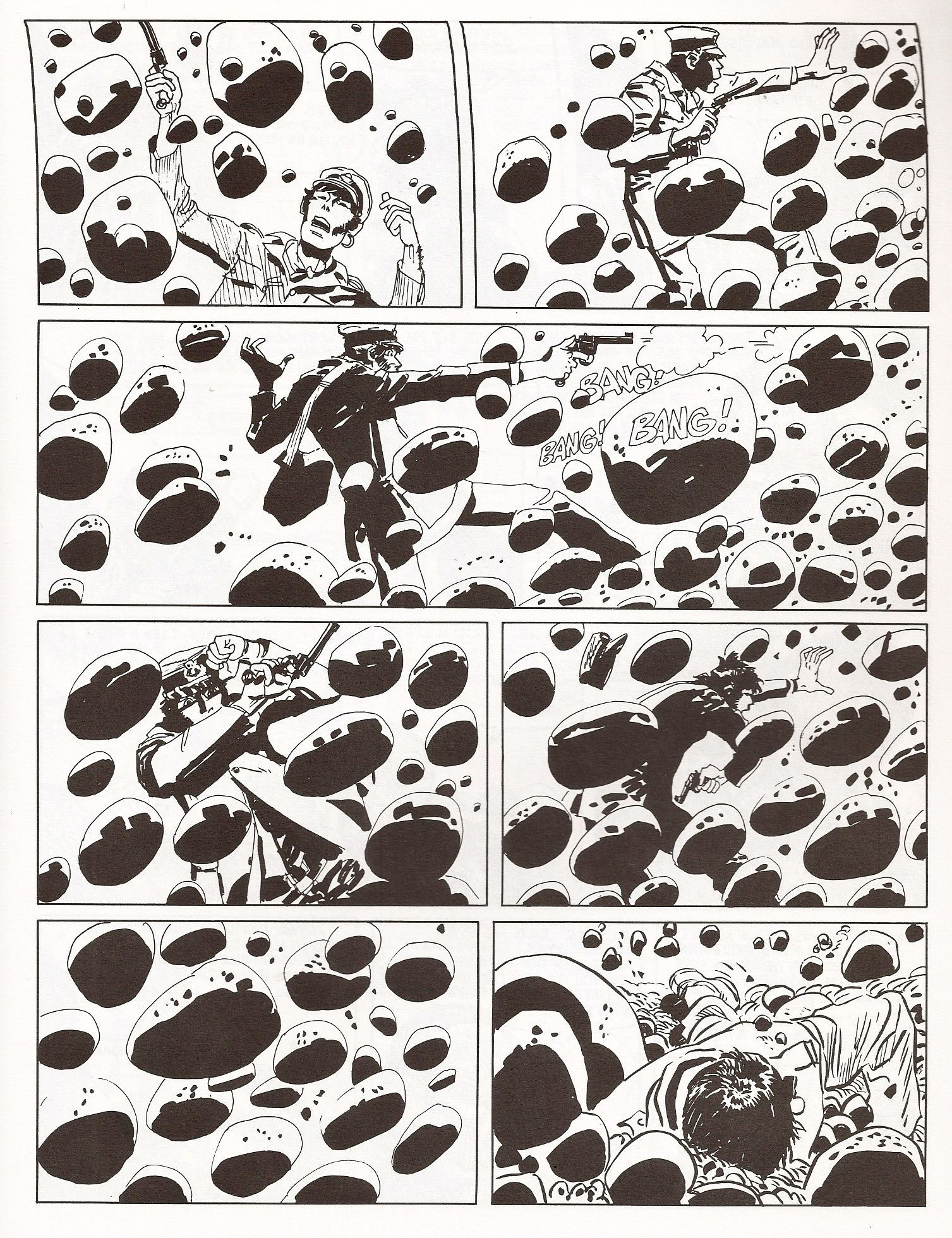

Corto Maltese in Africa (1978), page 51. Hugo Pratt.

American action cartooning has Jack Kirby, the Japanese have Tezuka, France has Herge -- and in Italy, there is Hugo Pratt. Like all the truly great cartoonists, Pratt picked up his country's comics tradition and moved its trajectory into line with that of his own work: the epic historical adventures contained in his Corto Maltese saga provided a stylistic blueprint Italian cartoonists would draw on or react against for decades after the series began appearing, and Pratt has provided inspiration for comics artists around the world -- Paul Pope is an avowed devotee, Eddie Campbell and Mike Mignola picked up more than a few lessons, and hey, does anybody remember the name of the contested island that provides Frank Miller's Dark Knight with its nuclear conclusion? It seems bizarrely fitting that in the week Moebius passes on, the English-speaking world should be reintroduced to late 20th-century Europe's other foundational cartoonist via a new series of Corto translations.

Like Moebius, and a many more European action artists, Pratt's work has a deep basis in the comics of Milton Caniff. Vistas stretch back as far as a panel can describe, exotic adventure is everywhere to be found, and elegant, brushy inking is the tool put to most frequent disposal. But where most of the European comics that have made it to English used Caniff's influence in tandem with those of Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, as a launching pad for increasingly meticulous and fantastic detail, Pratt went the other way, embracing the graphic bluntness and simplicity of approach found in Roy Crane, and even George Herriman. At their best, Pratt's pages feel documentary, drawn from firsthand observation as much as imaginative fancy, perhaps by an observer standing on the sidelines as the action on them thunders forth. Everything in Corto Maltese has a strong basis in realism, from the solid weight of the figures to the straightahead, camera-on-the-ground blocking to Pratt's stoic, unforgiving way with an action plot. It's action comics whose practice matches their content: rough and unwavering, achieving transcendence via a series of echoing, visceral smacks.

None of it would work without Pratt's downright monstrous drawing ability; of everyone to have inked their comics with a brush, it's difficult to make the case against Pratt as the best who ever was. The sequence above is a perfect example of the sense of great haste his savagely marked, blotty German Expressionist inking brought to his pages. The overwhelming impression is one of drawings done at a furious clip, set down as quickly as possible so as to be prepared to document the next moment on. Form matches content -- Pratt drew like a landslide. But behind the loose, unstoppable rush is a structure so solid that even the hardcore minimalism of his cartooning never so much a trembled its foundations. Single Pratt panels often barely look like more than a random scattering of squeegeed brushstrokes, but then in the next panel on the marks have rearranged themselves just so, and though the characters or camera angle's moved, the shadows still fall in the exact same direction. Pratt saw his pictures with such clarity, that he could excise massive, gaping holes from what he put on the page, leaving only the blackest of the shadows and a few casually scrawled rendering lines for flavor.

Such a bold graphic sense is rare in comics -- Crane had it, and so did Alex Toth -- but what's really special is seeing comics done so close to the ragged edge of abstraction succeed so effortlessly as barnstorming action material. This is what makes the page above such a wonderful example of what Pratt was all about. Click on the image to look at how striking an abstract motif the falling rocks create across the entire page: evenly spaced circular areas of black slowly clustering closer and closer together as they move down a grid. And panel by panel, the effect is just as bold -- a human figure being assaulted by slapped-down marks, first raising his hands to protect himself from them, then slowly growing more and more shadowed as they pile down, their shadows eventually becoming almost indistinguishable from his own. It's an avalanche of ink, a page's figurative content going up against the power of pure shape and design, and as the sixth panel makes clear, the winner is inevitable. Pratt's stories are a delight to lose oneself in, and they linger in the mind once the books have long since been put down -- but in the panels themselves, the raw purity of those black spaces speak in a voice louder than anything else, until nothing beside can be heard.