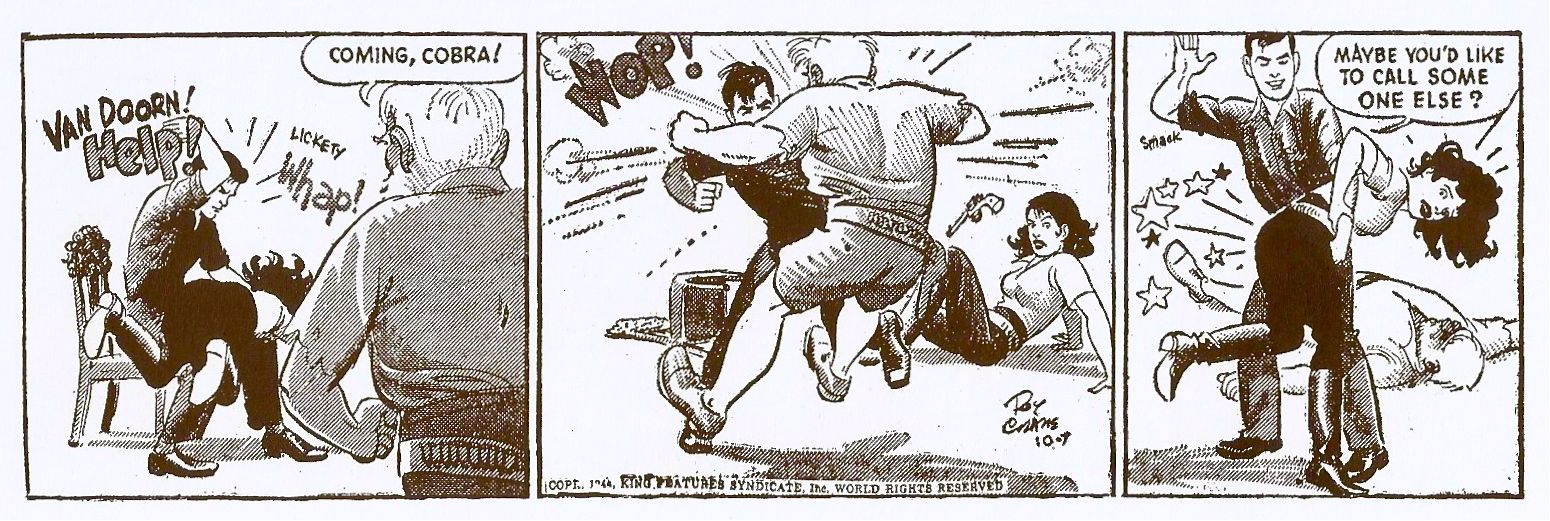

Buz Sawyer for October 7th, 1944. Roy Crane.

If it isn't quite a lost art, the daily comic strip is certainly a format on the wane, and that's a pretty terrible shame as these things go. More great comics have been presented in this form than perhaps any other (Krazy Kat, Peanuts, and Calvin & Hobbes make a pretty stiff argument all by themselves), and the ties to the medium's earliest history the strip provides shouldn't be overlooked either. But most importantly -- most interestingly -- strips present comics in their most compact, immediate form. No less than two panels, very rarely more than five, they're almost exclusively a reading experience of a minute or less, and as such they encourage a direct, no-frills approach that stands refreshingly at odds with so many long-form comics, in which complexity is seen as a cardinal virtue.

The best comic strips are sequencing at its purest and most simple: a situation is introduced, step one, and then complicated, step two. It's always more than can fit in a single picture, but never too much to be understood in much longer than an instant. The setup rewards swift action and snappy comedy, and though there's plenty of room for subtlety the premium that strips place on broadness is more than what makes them fun to read -- it's a big part of why comics became the immediate, populist form they did. In its early-mid 20th century heyday the newspaper daily strip serviced a vastly different audience than today's comics industry does: it was taken in each morning by the millions, designed for a workaday audience who read the material in a hurry and couldn't be expected to place much more of an emphasis on the fine points of their comics' aesthetic appeal than their breakfast cereal's. In the dailies that provided the comic book format's first wave of practitioners with inspiration, the point had to come across, and quickly, if you please.

Roy Crane was one of the best who ever lived at getting to the point, and even better at making sure said point was worth getting to. His panoramic Sunday pages are marvels of cartoon invention, but it's in his daily strips that Crane's stripped-down cartooning and brash, amplified style shine brightest. Think of Crane as punk rock a few decades too soon: stripped of color's filigree and confined to a few panels' worth of nervy energy, he moved quickly, accurately, and with purpose. There's a strange fascination to seeing material like the deeply kinky spanking strip above, displaced by decades from its home time. What today is both highly problematic misogyny and incredibly overt sexuality was literally yesterday's funny papers -- and such is Crane's way with (not to mentio n his obvious passion for) such content that it's as easy to understand the strip in its 1940s context as the one today's mores give it. Few cartoonists, then or now, have cut to the core of populism with their content the way he did: Crane comics are all girls, guns, and high adventure, drawn so pleasingly it seems a shame not to look.

But to write off Crane as a bigfoot-cartooning purveyor of schlock is to miss the great subtlety he brought to everything he drew -- again, his dailies most of all. Given such a miniscule amount of space to convey something of substance, Crane became one of comics' great minimalists, fitting great gulps of information into his every panel, and doing it with such consideration that everything simply reads, coming across without asking any extra effort of the reader. The strip above showcases Crane's ability to be simultaneously compressed and economical as much as it does his barnstorming, crowd-pleasing content.

Panel one uses multiple depth planes, foreground and middle ground, to fit two panels' worth of story into one, and drops out the background entirely to keep the visual pace lively -- enough of a stage is sketched out by the deft placement of the shadows on the ground and the solidly rendered chair that provides the panel's sole bit of scenery. The main action sits smack in the strip's center, as Crane manages to communicate the adrenaline of a whole fight scene with a single corker of an impact shot. The panel's more than visual TNT, though -- there's an entire story in it. The upset chair and sprawled girl testify to hero Buz Sawyer's hasty reaction to his antagonist's entrance, and the gun flying from its owner's grip fills in a bit of information lost by the first panel's tight framing. Best of all, the flying figure of the heavy being laid out is a sequence in itself when read top to bottom: taut muscles and clenched fists on the top half, still ready for action, even as the flying feet on the bottom half let us know the fight's outcome. By organizing the content of the first tow panels the way he does -- spare on the left, with visual information massing on the right, Crane hauls the eye across his sequence at such great speeds that the backgrounds and connecting actions simply aren't missed. The third panel is a repeat of the first, enough to draw a massively guilty-pleasure type chuckle at the sheer brass Crane was putting into this stuff. It also gives the strip as a whole a highly pleasing element of design: two lower-impact spanking shots provide a perfectly symmetrical frame for the big blow-up in the middle.

Crane's visual style is a perfect match for his content: about as stripped down as action cartooning gets, it throws a few simple shapes together to build figures and then slams them into each other at high speeds. Everything's given a massively appealing element of the illustrative, however, by Crane's virtuoso use of screen tone, a middle gray value to complement the high contrast of his blacks and whites. The final product is "realist" action comics long before it was conceptualized as such: cartoons given the sheen of reality, their overblown actions made to appear serious for one flickering moment at first glance. If the comic strip's emphasis on directness and verve draws a line to the medium as it stands today, Crane's action comics are a clear forerunner to the modern era's, an appealingly crude attempt at convincing the audience that the brawny brawlers and shapely she-devils on the page are just a touch more real than they should by all rights be. And of course, what the graphic novelists take month after month and page after page to put across Crane does in three panels. Come October 8th, he was on to the next one.