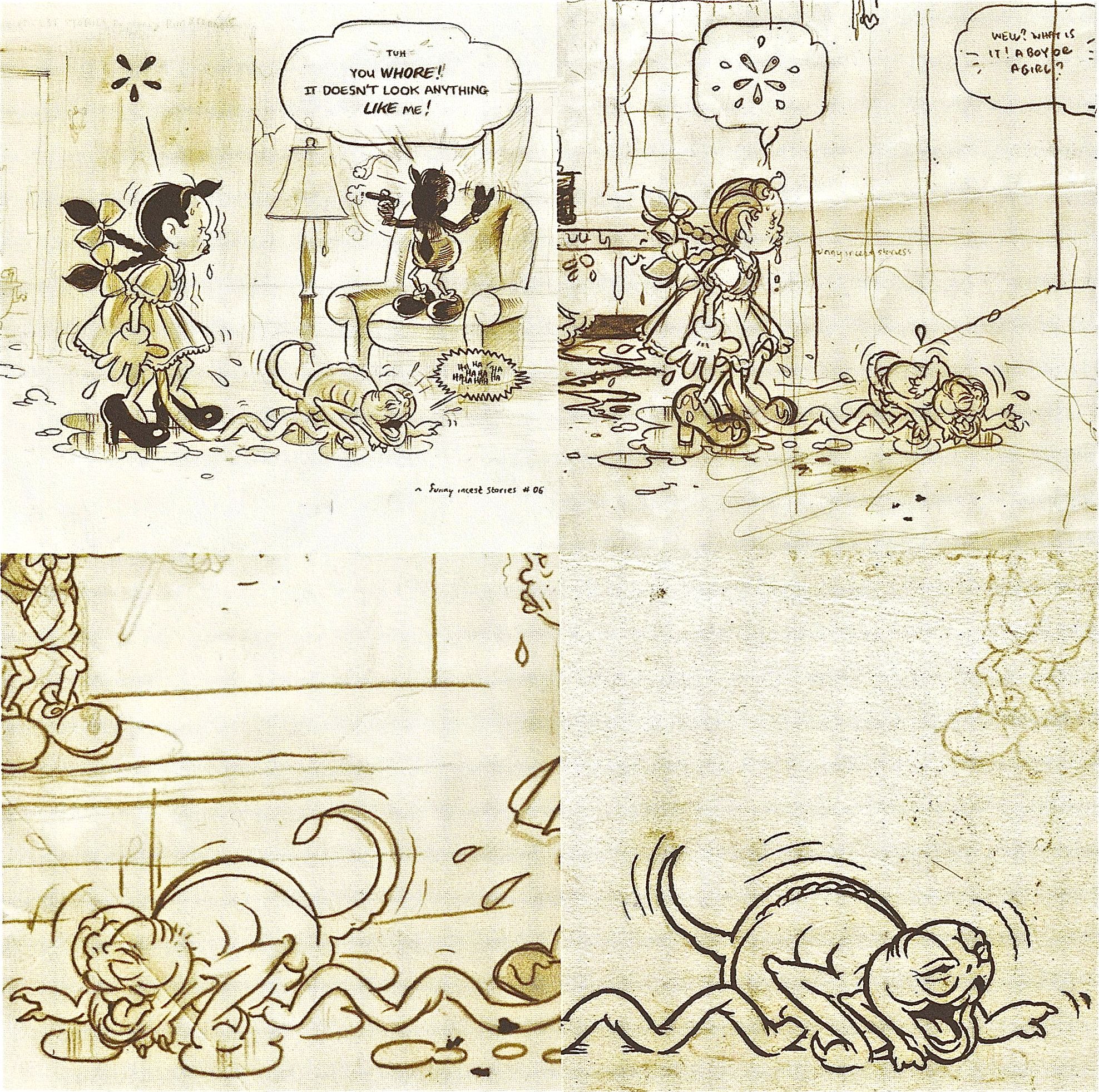

Pim & Francie: The Golden Bear Days (2009), page 23. Al Columbia.

Of course, no matter how realistically drawn or meticulously framed they get, no comics can even come close to accurately depicting reality; or even approximating it, really. When the human eye takes in the work of comics' great photorealists -- Alex Raymond, Neal Adams, Alex Ross -- the message it sends to the brain speaks of a certain closeness to the look of the real, but the first thing it tells us is always that we're looking at a drawing. This is why comics seem somehow lacking whenever they position themselves in competition with film: what that medium depicts is reality, stripped of a third dimension and re-presented at a later date. Comics, which can never escape their fundamental identity as works produced by human hands, are a medium of approximation, forever suggesting the existence of their content, never crossing the line into literal reproduction of anything that's actually happened in the real world.

(The exception to this rule is Italian fumetti, or photo-comics, but those mimic the action of the art form so clumsily and have produced so little of merit that they honestly aren't much worth discussing.)

But perhaps even more than the drawings that constitute them, the other thing that divorces comics from accurate depiction of reality is the same thing that makes them "comics" at all: sequence. The content of what we percieve as real, of course, unfolds in a continuous stream, never pausing or ceasing to exist even for a moment. Most art forms mimic this to some degree or another: music is perceived as continuous even when it contains sections of total silence, the vast majority of film never stops moving, and even most prose writing operates in a single stream, cutting itself off and restarting at break points only occasionally. The comics panel is the most independent single unit that exists in any art form -- complete in and of itself, distinctly separate from those around it. Any connection to the previous or the next is brought to the page by the reader: divorced in physical space as well as story time, it takes a highly abstracted reading of comics to see the lines that make up one character from one panel to the next as "the same", or the action of two different pages as occurring in a single setting. The fact that this is the reading we all give comics every time we read them changes nothing. Sequence is what creates stories in pictures, but it also never stops interrupting them.

But that divorce from reality gives comics a strength that no other form holds in greater store. Comics is the medium of the visionary, and has been since long before the word "comics" was used to describe picture narrative. From illuminated manuscripts to altarpieces to alchemical writings to the works of Blake and Dante, texts that describe human experiences with something beyond or outside of everyday reality have used the action of comics to present themselves. The work of Jack Kirby proceeds from this use of comics, and so does that of Winsor McCay, George Herriman, Frank Frazetta -- all of comics' great fantasists.

Interestingly enough, the best object lesson I can think of for the comics form's total lack of realism comes from one of its more prominent realist draftsmen, Al Columbia. In many ways it makes total sense that someone who worked on the photorealist borders of the form for a good part of his career -- as assistant to Bill Sienkiewicz, no less -- would be the one to bring back a great knowledge of comics' basic identity as a string of suggestions. The genius of the page above is almost too simple: in four panels that follow the minimalist logic of the gag-strip format, it speaks to both the artificial nature of drawings and to the nature of sequence as something that breaks comics apart as much as pieces them together.

The first panel above is comics more or less as we know it, with full figures fully inked and captured neatly within one frame. It's in panel two that things start to get challenging: the foreground is almost identical to that of the previous panel, but the background has scrolled to the side, cutting off both the panel's speaker and his word balloon. More interestingly, loose pencil lines spread out across the panel, depicting nothing but making it unavoidable that we view the image as a hand-drawn artifact as well as a piece of visual information. The crease spreading across the second panel and the severe, borderless digital cutline between frames make it obvious that these two images were drawn on separate pieces of paper; that is to say, that they never shared space until they were pieced together on the computer for the printed book. Panels three and four continue to draw the reader's attention away from the drawings' content and toward their lines-on-paper identity, zooming in for cropped details of the panels rather than the entire drawings. The inks are dropped completely from panel three, bringing it as much into dialogue with the scattershot pencil marks in the previous panel as the figures; and in panel four just about everything but the hideous creature at the bottom and the paper grain itself has disappeared.

It's impossible not to take in the tools that were used to create this page's content as much as the content itself. Both are given equal prominence here. It's a strange way of making comics, one that keeps readers at arm's length by reminding them that what they're reading has nothing to do with reality; but the dislocated headspace this creates is perfect for the stomach-churning content of Columbia's page. The effect of the page's progressive discarding of the story set-up that it begins with is more than a formalist exhibition -- it's a great piece of horror storytelling, forcing readers into a direct confrontation with the soggy, quivering abomination that's all too easy to shudder past in the first frame. By the end all that remains is the paper and what's drawn on it, in more or less equal measure, and when the drawing is this disturbing, contemplating the weathered texture of the pictureplane becomes uncommonly tempting.