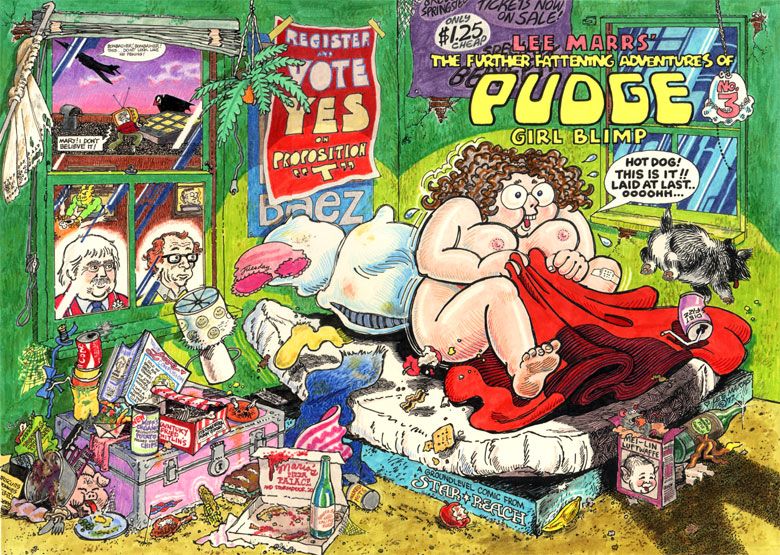

As an award-winning cartoonist, animator, writer and humorist, Lee Marrs has enjoyed a storied career, yet for many of her fans she is primarily associated with the underground comics scene. Though her "Further Fattening Adventures of Pudge, Girl Blimp" series has been out of print for years, it remains a beloved cult hit, and she hopes to see it collected in the near future. Marrs was also one of the founding members of the Wimmen's Comix Collective, and "The Complete Wimmen's Comix" will be published early next year by Fantagraphics.

Marrs, who retired this year as Chair of Multimedia Arts at Berkeley City College, spoke with CBR News about what the future holds. Over the course of an hour-long conversation, we barely scratched the surface of her long career, which she said in no uncertain terms hasn't even come close to an end.

CBR News: I know that one of your first jobs in comics was working as assistant to Tex Blaisell when you were still on school. How did that happen?

Lee Marrs: I met his daughter Barbara in college, and we became best friends. When I was visiting her, I met her dad, and he quickly realized in his mind that I was very talented. This was a revelation to him, because he was of the WWII generation of male artists who thought no girls can draw. I began assisting him whenever I was in New York. I got to assist on "Hi and Lois," "Prince Valiant," "Little Orphan Annie." Then there were various comic book work that I assisted him on as well.

Why didn't you continue assisting on comic strips, or try to get your own strip?

Because I was ambitious. I was interested in having all this work, in a business sense. From my experience with Tex, I learned that both the comic book world and the strip world were wretched. The pay scale was nothing, and you had no rights. I was particularly struck by your not having any rights to the material.

How did you go from wanting to be an editorial cartoonist to making books like "Pudge?"

When I was in college, Herblock (Herbert Lawrence Block) -- who was the Washington Post cartoonist, a famous guy then -- had already seen my work. I went to college at American University in Washington, DC. He had said to the editor of the school newspaper, have this guy see me when he graduates.

Having Lee as a first name became useful. [Laughs] So I went to see him, and he was very shocked that I was a girl. We had lunch and he looked over my stuff. He said, what you should do is go back to your hometown and get work on the paper and then do cartoons on the side until they see how good the cartoons are. That's the way most people do it. I said, well, my hometown is Montgomery, Alabama. Herb was shocked and said, don't go back to your hometown! [Laughs] Because, of course, all my cartoons were progressive or edgy. He explained to me that there were no women political cartoonists in the United States.

That was where things stood back then? There were no women political cartoonists out the hundreds across the country?

He said, unless I wanted to move to Canada or Europe, this was going to be an uphill battle. Nevertheless, he did give me letters of reference to several of the newspapers that syndicated his work for me to send around. He helped me choose which work to include, but he said, it's probably not going to go anywhere. I did that, and got a few letters back. Most people I didn't hear from. It was a body blow, because there didn't seem to be any way to work this out. Then, answering an ad in the Washington Post for a graphic artist for a TV station, I fell into a situation where I worked for CBS News in Washington DC at WTOP. I began to do all the artwork for the station, but on Saturday nights I did live an editorial cartoon. The news director happened to be looking in on one Saturday night, and he instantly called up the station and said this can't continue because I was doing progressive stuff on what was a conservative station.

I sort of abandoned doing cartooning and emphasized my straight artwork in order to get work, first at WTOP, and then once I moved out to California, I worked for a TV station in San Francisco. Then they had layoffs, and under the principle of last hired first fired, I was in California without a job. But I had been completely won over by the San Francisco life. This was the last of the '60s, and then I had all the various jobs that you would have where people are working as sitting room checkers and just doing grunt work.

During this time, you also started a syndicate for comics and features.

I helped start, with two other people, Alternative Features Service. It was a feature news service for college papers, underground papers and regular newspapers. During that time, we needed illustrations, and I ran across Trina [Robbins'] work. It was through talking with Trina I learned about underground comics. There was nothing on the East Coast like this. I went to head shops and saw that there was all kinds of wild and wooly stuff, and I began to work on my own work. The idea that I could do cartoons that nobody was filtering, was just me, was great. It took decades to learn that there was no money in that. [Laughs]

One of the most interesting aspects of your career is that you were including so much personal work in your own comics and different anthologies, but you were also working at DC and Marvel starting in the '70s. How did you start working with Joe Orlando?

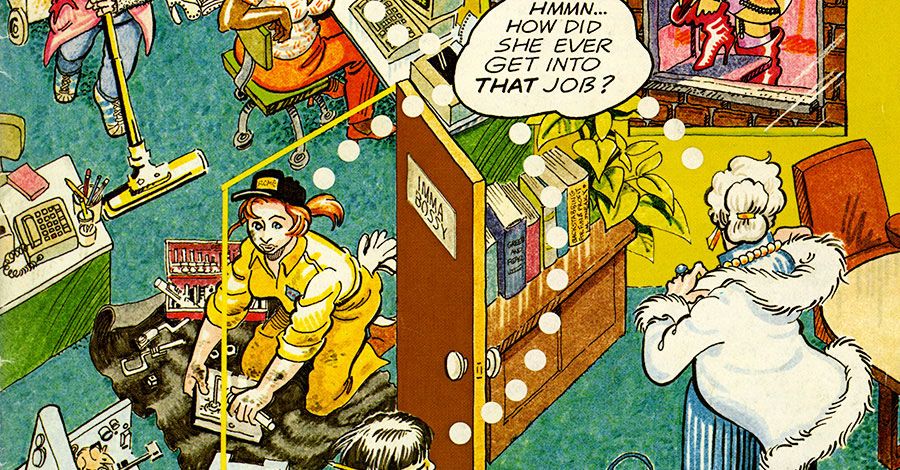

That was through Tex Blaisdell. Joe came from "MAD Magazine" originally, but by this time he was editing books at DC and he really liked my work. It was his kind of sense of humor, but he didn't have any venue. He was editing "Weird Mystery" and such, but Joe was the kind of editor who wanted to give all of his friends -- his old friends, going back many years -- work, and none of them did humor work. He wanted to start up his version of "MAD Magazine," and that eventually became "Plop!" At this point, everybody who did comics lived in New York, Connecticut or in New Jersey. They were all around New York. I could draw really fast, and because I wrote as well, he would mail me scripts. These were supposedly funny scripts, for the most part. There were a few that were very funny -- those were written by Mary Skrenes and Steve Skeates -- but most of them were straight scripts that had one joke. I would change the story, or put bits in the art that would make them more amusing. This went on for years. It was really a good gig.

And of course you had this opportunity because "Plop!" -- unlike "Mad" -- actually employed women.

[Laughs] Yes! Joe was a great guy. He realized that particularly the way the world was going, there was all kinds of humor and creativity that the World War II guys were not managing. He knew one way to deal with this was hiring a hipper bunch of people to make comics.

You've always been doing so many things in different directions. How much was this you being curious and wanting to try new things, and how much was just you taking advantage of opportunities?

If I had been able to make a living doing comics, I would have done that for my whole career. I would have just concentrated on comics, but there was no way to do that. I'd always been a person interested in a lot of different things. I was an animation fan, for instance. I took a couple courses in animation and started an animation career, but it was fueled by economics. [Laughs] Lee Marrs Artwork ran for thirty-something years, and got into a lot of different things. For instance, most of the animation done ever is not entertainment. It's not movies. It isn't even television. It's medical work and legal work and advertising work. This was before the second golden age of animation that we're in now. Through that, by doing all this work for different companies, I got a chance to learn a lot of different things.

I always say, the one good guess, career-wise, that I ever made was, I figured out in the late-'70s that the way computers were going, computers would be used in animation. This was the beginning of 3D animation. This was the start of a new field. In the late-'70s I took a couple of classes in computer science at UC Berkeley. I was thinking I have to decide either to move to Utah or New York City which was where the only two places that 3D animation was getting its start but Silicon Valley popped up at the same time. I was one of the first and maybe the only animator to get into computer graphics at the very beginning.

Lee Marrs Artwork was how I got into all these different kinds of work. When I was in college, I saw that storytelling was the key. If you could tell a story really well, it wouldn't matter how sophisticated the artwork was, or how elaborate the artwork was. It would be effective. Storytelling was the basis of all the animation work I did.

I did quite a bit of work for the state of California. I worked for advertising agencies doing storyboards. Invariably, they would call at 6 o'clock on a Friday night and they needed three storyboards in color by Monday morning at 10 -- and they would pay triple in order to manage that.

Once you started working in animation and you also drew storyboards for film, did it change how you approached comics?

It made the style of the comics much more simple. Originally, I was doing the cartoons as though I were a fine artist, so I would put in textures and chiaroscuro and all kinds of deep stuff. My work became more stylized from doing storyboards and other animated work.

You were writing and drawing comics sporadically in the '80s and '90s, working on "Wonder Woman," "Viking Prince" and other books. You also made something called "Pre-Teen Dirty-Gene Kung-Fu Kangaroos."

[Laughs] You found out my secret! The publisher called up and said, we can make a bit of money if you crank this out. That was cranked out.

To prepare for this interview, I read your "Indiana Jones" comics, and they read differently than a lot of the ones other people wrote.

I loved that. That was another job that I could have had for decades and really enjoyed it. From the fan mail, it seemed to really strike a chord. All of the books had to be vetted by LucasArts. This seemed to be a really tricky prospect, but in doing the stories, I just stuck to their formula. Because I enjoy history and I had years of National Geographic, I could easily just look up stuff and work up stories based on that.

One long story I had to do was based on the Indiana Jones game they were going to come out with. They wanted the story to reflect what was in the game. By this time, I'd already been doing work in games and I saw that this game would probably never see the light of day. Their idea was to include the comic book in the game, and that was a nightmare. I would write a script, and then a couple of weeks later they would say, oh, it can't happen in Germany -- it's supposed to happen to Ireland, now. Then I would have to change everything. But I put on a ten percent contingency fee on that, so at least they paid for all that indecision. They were going to launch another round of Indiana Jones books, but River Phoenix died and that scrapped that movie.

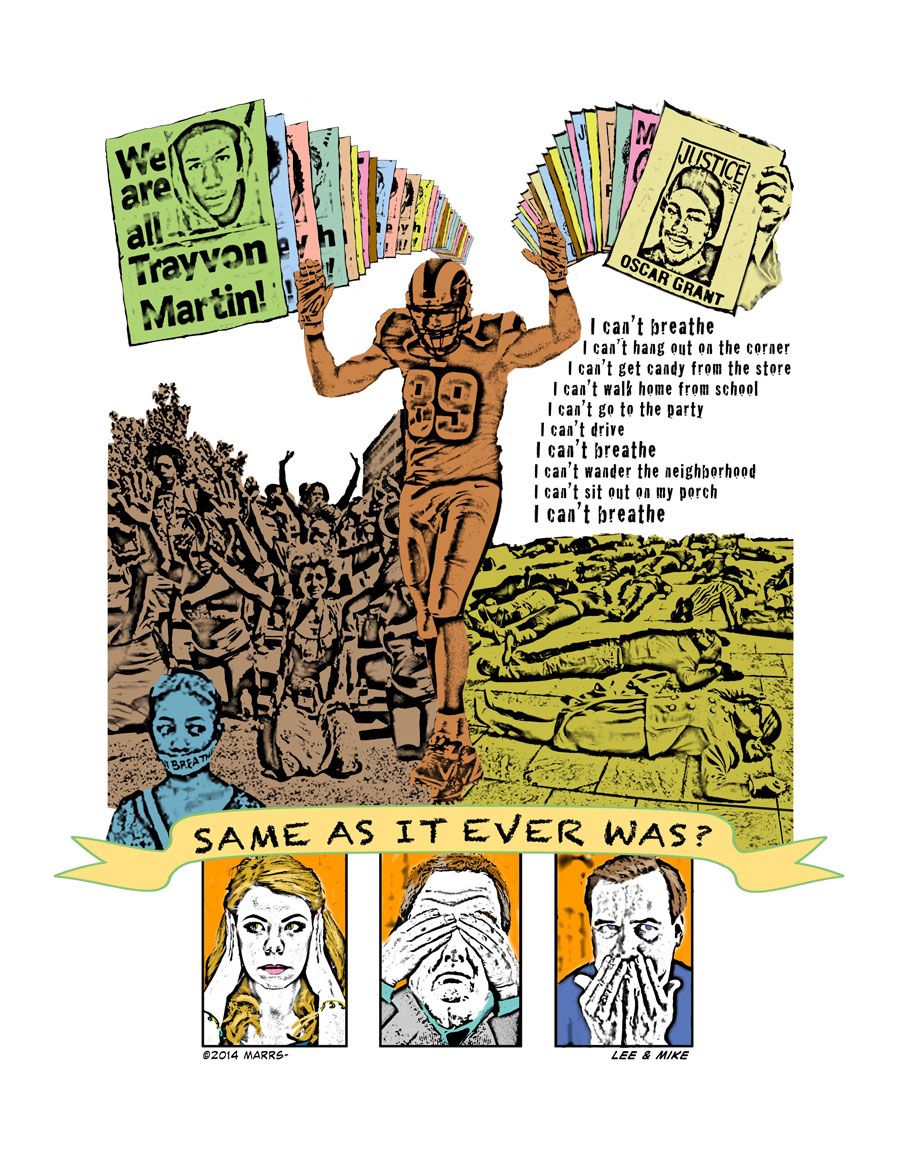

Do you ever wish that you'd tried to be an editorial cartoonist?

What's happened over the years is, I put out a cartoon or a graphic every year at Christmas, and that's been my editorial cartoon for the year. I don't think I ever had the opportunity after WTOP to do it professionally, but I have done it in my own personal work. For years, I was a member of a city organization here in Berkeley called Berkeley Citizens Action, and I did cartoons and promotions that were editorial cartoons, in essence, to promote the work that they did.

Do you have plans to collect your older work? There's a lot there.

Yes, I do have a lot. [Laughs] I'm trying to straighten out my studio -- or I should say dig out my studio. It's an archeological dig. I was going through all the comics work, and there are thousands of pages. It's amazing. So yes. I can see getting together the gay work, the science fiction work. We'll see. With print on demand, all kinds of things are possible.

It seems there are people who are familiar with my funny work, but they don't know about the science fiction and adventure stuff. There are fans of the science fiction and adventure stuff but they don't know about the funny stuff.

For the longest time, all I knew of your work was the Vertigo miniseries "Faultlines" from the '90s. Which I liked, but I'm sure that being the only frame of reference for you is odd.

[Laughs] There was a whole universe there. It's too bad it didn't go further than the first story. The idea for that came from my game work, actually. I've always liked creepy stories and things about ESP and such.

Do you have ambitions to do more right now?

I have several projects. I'm working on one now, but there are others. I hope to get out "Pudge, Girl Blimp" as a book. There are family stories. I had a weird family and I'm writing and illustrating them because by now there are younger relatives, grand-nieces and grand-nephews, who won't hear these stories otherwise.