Writer Nick Spencer faced an overwhelming amount of backlash on social media after the release of "Captain America: Steve Rogers" #1, which revealed Cap had secretly been a Hydra agent since the very beginning of his career. Much of the criticism directed at Spencer was from those who hadn't read or even seen the comic; some of those who had read the issue and condemned the development were also unaware of the of the events leading up to it, particularly the ending of Spencer's preceding "Avengers Standoff: Assault on Pleasant Hill" event, where Steve Rogers' youth was restored by Kobik, the childlike manifestation of the Cosmic Cube. While the second-issue revelation that Kobik had altered Cap at the behest of the Red Skull quieted a lot of the armchair critics, these first two issues haven't been without their critical shortcomings -- but they are atypical for Spencer's current body of work.

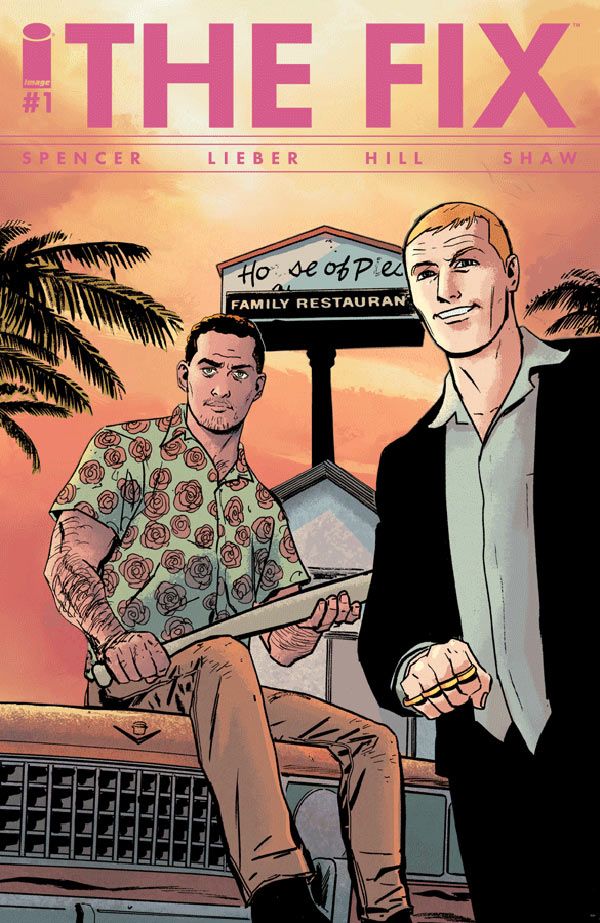

Spencer is the first writer in nearly two decades to write two "Captain America" titles concurrently. In addition to the more capable "Captain America: Sam Wilson," he also pens the lighthearted and enjoyable "Astonishing Ant-Man" for Marvel Comics, as well as his creator-owned Image Comics series "The Fix." The latter title is a strongly conceived series about two crooked LAPD detectives who are in over their heads with a mob boss, and it centers on their darkly comical efforts to launch a scheme to pay him back and hopefully become movie stars in the process. "The Fix" offers a real contrast for the kind of storytelling seen in "Captain America: Steve Rogers" and achieves excellence on nearly all levels, while "Cap" struggles with some basic storytelling fundamentals.

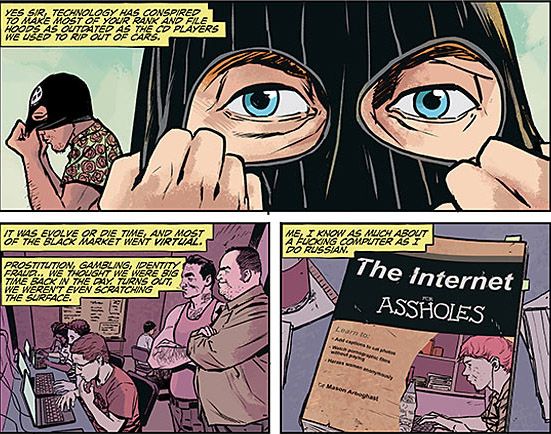

Over the first four issues of "The Fix," the creative synergy between Spencer and artist Steve Lieber has been all-but-perfect. Lieber proficiently facilitates Spencer's script, with stark transitions between scenes that evoke any number of emotions, from humor to tension to outright surprise. Brief flashback sequences -- sometimes as short as a single panel -- punctuate the script and keep it lively. There synergy over in "Cap" isn't quite so strong, though; the transitions here are jumbled and sometimes read like the writer and artist aren't on the same page, and the complexities of the story require a great deal of exposition that Jesus Saiz' art simply doesn't support. The muddled "Steve Rogers" storyline is accompanied by overcrowded panels, while "The Fix's" backstory-free characters Roy and Mac are crisply defined in Lieber's uncluttered layouts.

Based on the fairly brief and emotionless encounter between Steve and Sharon Carter, some readers might find it hard to believe the two had ever been in a romantic relationship, let alone that they're still involved in one. Likewise, Kobik's motivations to ally herself with the Red Skull feel contrived and convenient, and their budding relationship is presented as a kind of perverse father/daughter bond that ranks pretty high on the creepiness scale. Skull presents himself as a strange amalgamation of Max von Sydow's Ming the Merciless and Tim Burton's Jack Skellington as he laments about his boredom to his underlings and reveals his plan to corrupt Steve Rogers.

Roy and Mac are convincing in their corruption, though, and evoke an unavoidable sympathy in readers by way of their plight and misfortunes. The crime boss they're indebted to is the diametrical opposite of the Godfather or Tony Soprano; in fact, he's more along the lines of Rogers -- not Steve Rogers, but rather Mister Rogers, with his mostly soft-spoken, quiet demeanor. Quiet, yes, but also intimidating, with unanticipated outbursts that provide glimpses of his true nature that are quick enough to almost make readers forget what he's capable of, even as they convey his cruel ways. Even the supporting players -- like Mac's passive aggressive wife and the hedonistic child-star-turned-celebrity-train-wreck that Roy tries to manipulate to his own ends -- are superbly developed despite their fairly brief appearances.

Every character in "The Fix" gets their moment of quotable one-liners via dialogue or narration, although most aren't repeatable in front of a family-friendly audience. The exchanges between characters are sharp and lively and carry the longer periods of inaction. The narratives are often likewise lengthy but not decompressed, delivering a carefully-crafted punch. Like the story structure, the scripting itself excels at evoking various emotions and can jump from humor to tension and back again, adding texture to the story without disrupting it.

Meanwhile, the Red Skull discusses how celery makes a poor ingredient for soup and later reads a hammed-up, twisted bedtime story to Kobik, while elsewhere Maria Hill discusses her potassium intake. While the overall narration is competent, the dialogue ranges from flat to laborious, like when Baron Zemo delivers a rather standard, off-the-shelf supervillain rant, only to cap it off with a misplaced and out-of-character salutation.

In "The Fix," Spencer has the luxury of space and freedom that a self-created world can provide, and he not only uses that to the fullest extent possible but also capitalizes on the strengths of his artist to skillfully execute it. "Cap" has a few generations of history and continuity to deal with, and the bold tease put forth at the end of the first issue threatened to uproot that history -- a lofty and admirable goal on Spencer's part. Despite the often claustrophobic restrictions of Marvel's sandbox, it's a tease that might look successful on the macro level, but one that doesn't work so well on the micro. "Captain America: Steve Rogers" might be a series that deserves some criticism, but "The Fix" proves that such criticism should be applied only to the work, not to the skills of the writer behind it.