Our Dread Lord and Master can post ridiculously geeky polls, so I can too! I try to follow his lead in everything, after all, because he is Our Dread Lord and Master! (I should remind everyone that I tend to be more verbose than Brian, too, so this is a bit longer than his polls are.)

In the general discussion of why Jean Grey never worked as a character (I still say it's the writers' laziness, although many people made excellent points), I began to think abouteveryone's favorite mutant team. I am actuallyconsidering doing a compare-and-contrast post about Jean and Emma, because the English major in me just loves those compare-and-contrast things, but for now, I wonder which Era of Mutantcy is your favorite. I'm sure most people will say "The Phoenix Saga," but let's check out the choices first! Perhaps you will change your mind!

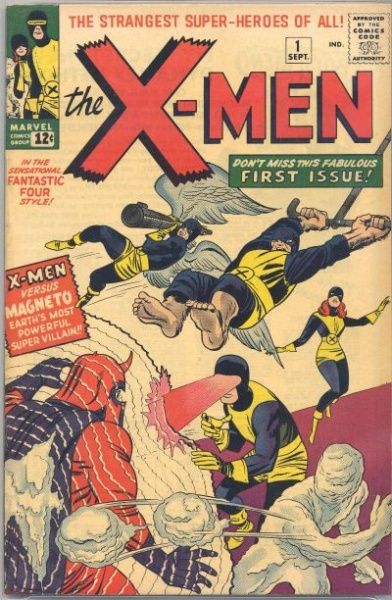

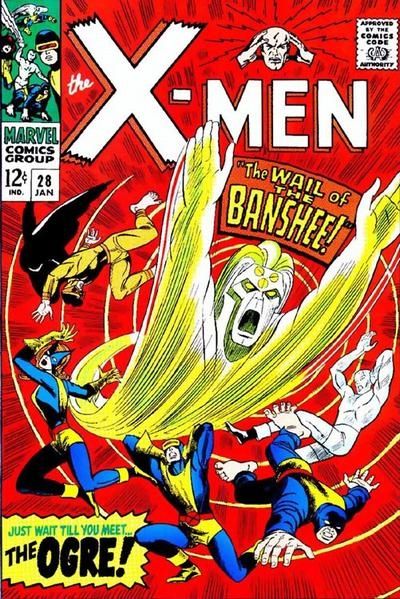

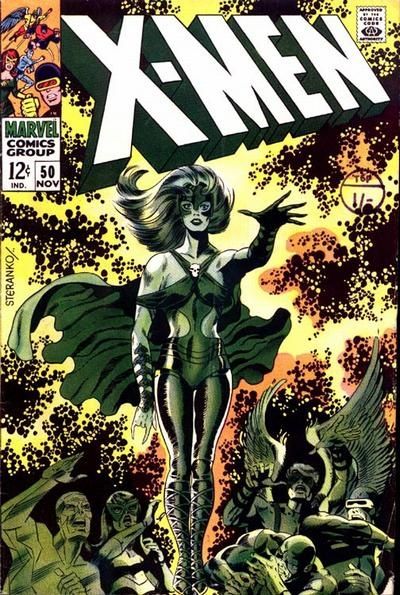

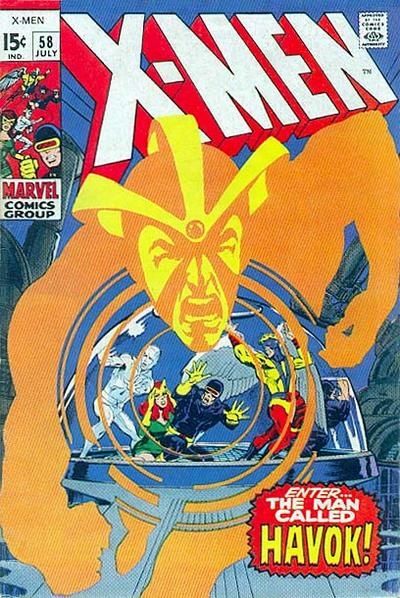

1. The Original Recipe Era (X-Men #1-66; September 1963-March 1970). The original team debuts, lasts a while, then gets cancelled when the sales of the book fall below 200,000. What an age! I haven't read many of these comics, because I'm not that interested in them, although the Neal Adams issues that wrapped up the run (with the exception of the last one, which Sal Buscema drew) are nice for the art and the introduction of Havok. I read about these issues over at the X-Axis, and it sounds like I'm not missing much. But if you love them, let me know!

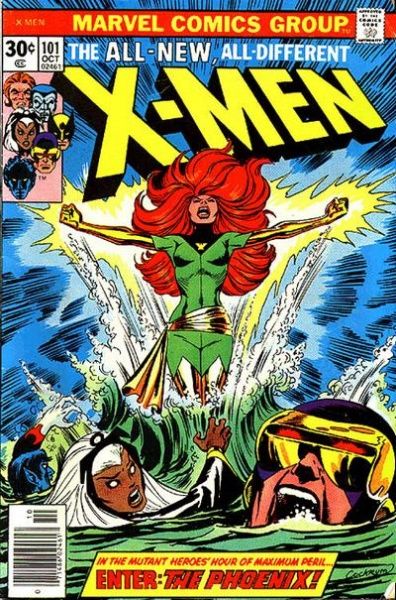

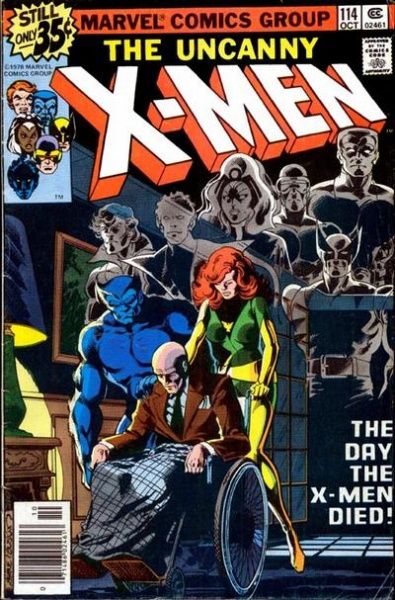

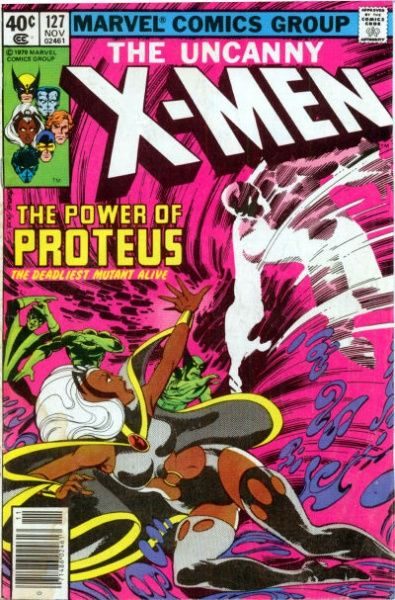

2. The Phoenix Era (Giant-Size X-Men #1& X-Men #94-138; July 1975-October 1980). I wasn't sure where to put the pre-#100 issues, as they aren't really part of the Phoenix Saga, but I figured it would be okay to lump them in with the post-#100 issues. This, of course, is one of the strangest publishing decisions in comic book history - X-Men #67-93 were reprints, and five years after the original issues ended, Marvel simply rebooted and started with a new team. These days, of course, they would just have a new #1 issue, but this is a bizarre way to go. Anyway, Claremont and Cockrum, and then Claremont and Byrne, give us a story about a superhero becoming God and what would happen. This kind of story played to Claremont's strengths - long-term plotting and pretensions of greatness - and Byrne's strong art and co-plotting gave us Phoenix saving the universe; the most powerful mutant ever in Proteus; and finally, the Temptation, Fall, and Redemption of Jean Grey. It's a very good storyline, especially because when you read it, even if you know Jean Grey comes back to life (one of the biggest mistakes Marvel ever made), it still feels very momentous and for a time it had very far-reaching repercussions. Plus, this storyline introduced us properly to that feral little weaselly mutant with the short temper. I understand he's quite popular.

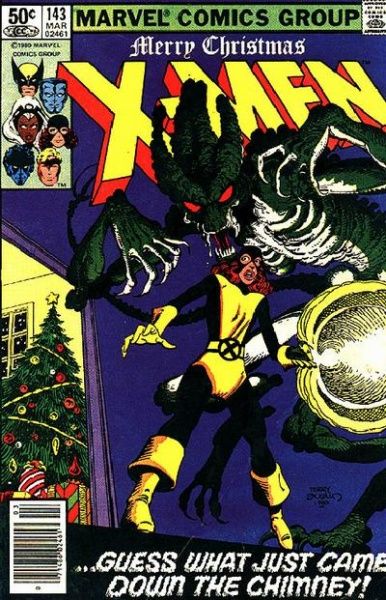

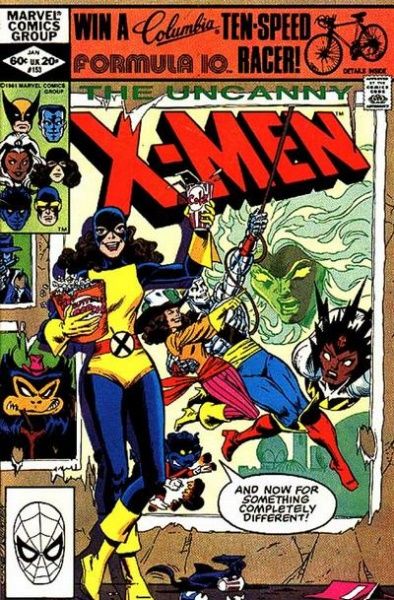

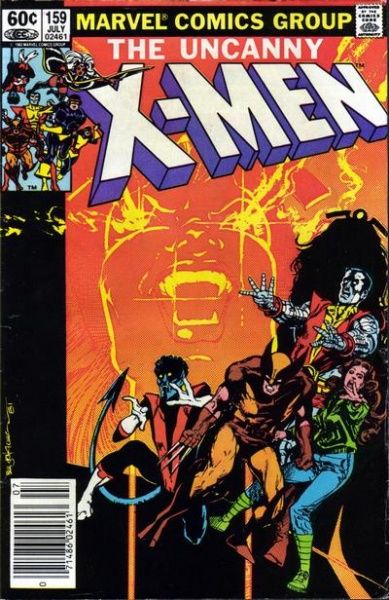

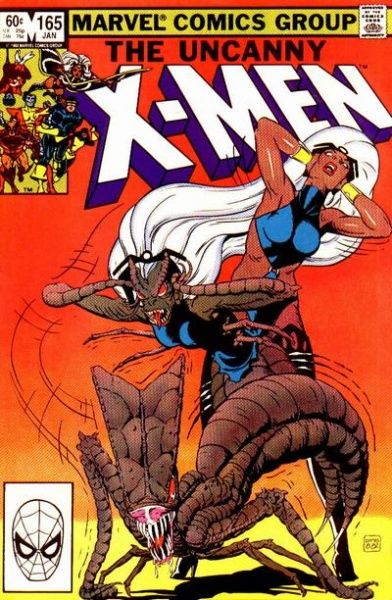

3. The New Blood/Brood Era (X-Men #139-Uncanny X-Men #167; November 1980-March 1983). I wasn't sure what to call this era, because it's kind of an awkward transition from the Phoenix Era to the next. In today's world, Claremont would have left the book, because that's what happens these days, but back then, everyone just moved along. It started well, with the introduction of Kitty Pryde after Scott left to wallow in self-pity and hook up with Lee Forrester. Then Claremont screwed the pooch in issues #141-142, "Days of Future Past," which on its own was a great story but led to a whole lot of crap. Then Byrne left the book with the excellent Christmas issue, #143, and things got weird. Cockrum returned, the book meandered a bit, and then Claremont decided to send the gang off into space again, this time creating an alien race that was NOT a rip-off of the movie Alien at all, the Brood, who menaced our heroes. The Brood saga, unbelievably, lasted a year (February 1982-83), although it was split into two parts, which broke it up a bit. I actually enjoyed the Brood saga - Storm turned into a whale (don't ask), Carol Danvers became Binary, Wolverine treated the Brood egg like a virus and rejected it, and Paul Smith took over the art chores. At the end of this era, Professor Xavier got the use of his legs back. How, you may ask? It's all about cloning, people!

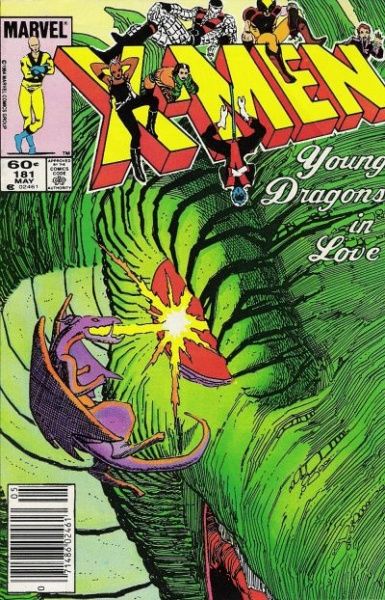

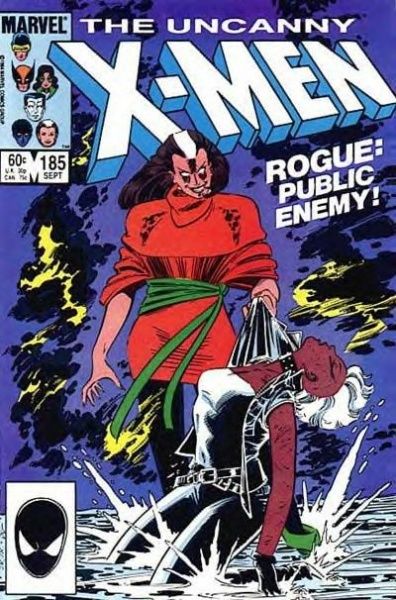

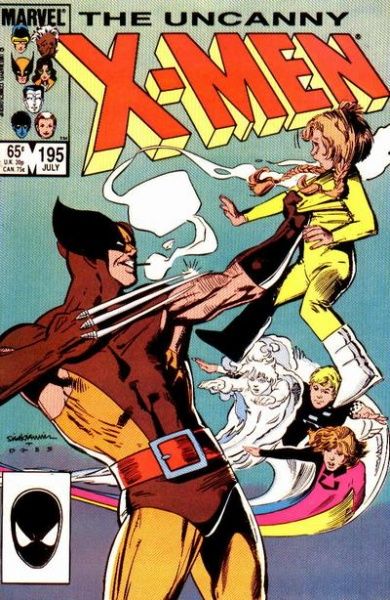

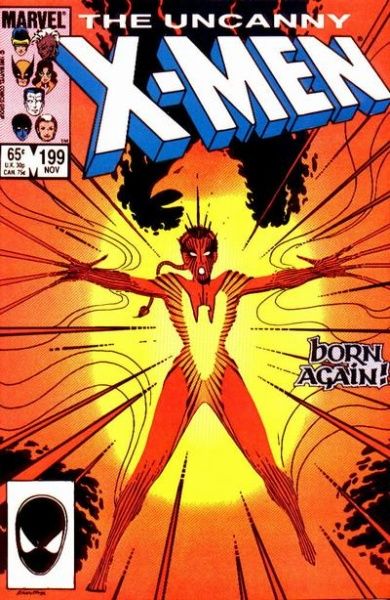

4. The Superhero Era (Uncanny X-Men #168-205; April 1983-May 1986). I call this the "Superhero Era" because this is really when the X-Men acted the most like a team doing standard superhero things. They didn't hang out ina headquarters and respond to alarms to go fight supervillains, of course, but the team was relatively stable (Kitty, Logan, Peter, Kurt, Storm, and Rogue, whojoined the team in issue #171) and their adventures relatively straightforward. We got the introduction of the Morlocks (and Storm stabbing Calisto through the heart, a great scene Lobdell ripped off 155 issues later); Logan's wedding (issues #172-73, two of Claremont's best); the fake Phoenix story with Maddie Pryor; Storm losing her powers; the Dire Wraiths story; the alternate reality New York story; and then Claremont's set-up for his big storyline that never occurred, with Nimrod and Rachel accepting the Phoenix powers and Xavier going into space and Magneto becoming headmaster and Scott losing a battle with a powerless Storm. At the end of this era, Claremont and Barry Windsor-Smith gave us issue #205, the fantastic snow-bound battle between a feral Wolverine and Lady Deathstrike, with guest star Katie Power. It's a great story. These issues are very good short stories, and toward the end of it, Claremont was beginning his next grand storyline, but it got short-circuited. Getting rid of Xavier was inspired, but making Magneto the headmaster was brilliant. Claremont never wrote Magneto as a true villain anyway, and his shift from bad guy to reluctant good guy was a great move and led to some very nice character development. Later writers (including the God of All Comics) dropped the ball with this, turning him back into a boring villain. Kind of a shame.

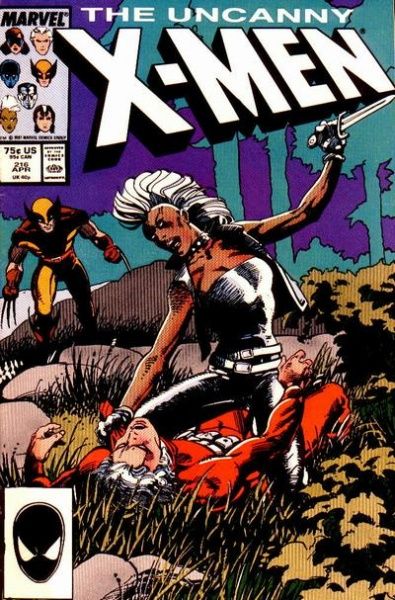

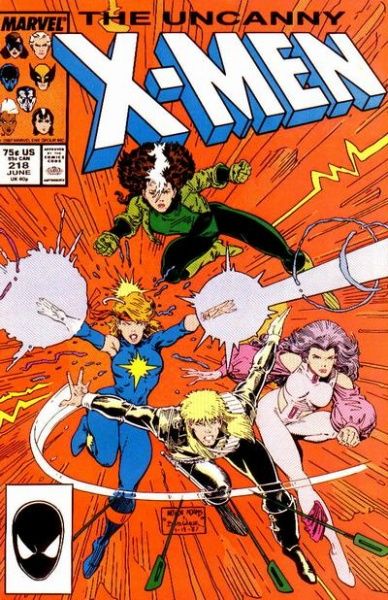

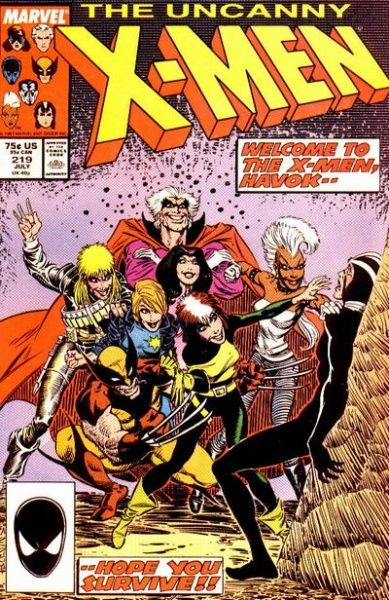

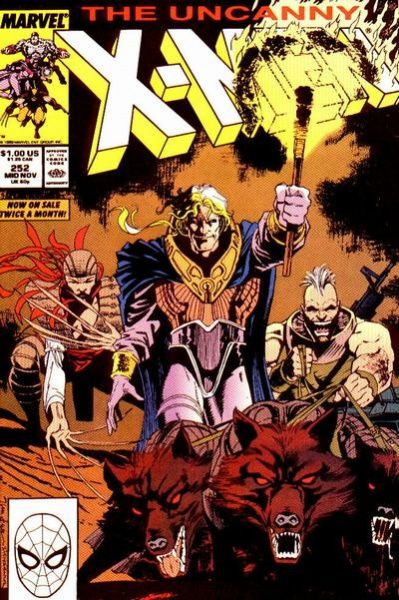

5. The "Things Fall Apart" Era Mark 1 (Uncanny X-Men #206-228; June 1986-April 1988). Issue #206 begins Claremont's next massive story, and we start with a great story about Wolverine almost gutting Rachel because she's thinking of using the Phoenix powers to mess with reality. This leads to a big fight with the Hellfire Club and Nimrod, and then the Mutant Massacre, which is an incredible arc that ripped the team apart. Kitty and Kurt were hurt so badly they had to go to Scotland to recover, eventually leading to the formation of Excalibur, Colossus killed that spinning dude (yeah, I know I should know his name, but I don't feel like looking for it - was it Riptide?), and we gotthe introduction of the Marauders, who were very cool for a while. Again, later writers messed with this story by having Gambit lead the Marauders to the Morlocks, which is dumb, but the raw power of the original story is still palpable. Then, in quicksuccession, Psylocke, Dazzler, Longshot, and Havokjoined the team, and things got weird with Forge, leading to the "Fall of the Mutants" crossover in which the X-Menapparently died savingthe world. This was a traumatic time in X-Men history, as Claremont destroyed a team that many people think of as the "classic"versionof the group. But it's a marvelous bit of storytelling, because not onlydid Claremont pull the rug out from under the readers, but it's obvious he had a plan, as well. A lot of writers destroy a team and just leave, but Claremont was in it for the long haul, and even though hedidn't get to follow through with his plans,these are still interesting stories. Issues #212 and 213feature two excellent fights between Wolverine and Sabretooth, but what makes #213 memorable is that Psylocke fights Sabretooth before Wolverine does, and holds her own (without all those fancy ninja moves she later got). Issue #214 had Dazzler possessed by Malice, which was neat. Havok joined a paranoid bunch of X-Men in issue 219, and their portion of the "Fall of the Mutants" story was pretty good, leading to the team's "death" on national television, temporarily making them heroes. This allowed them to become a "mutant strike force," which didn't work out too well, but was still an interesting idea. And it led them to, of all places, Australia, where the next era of Mutantcy would take place.

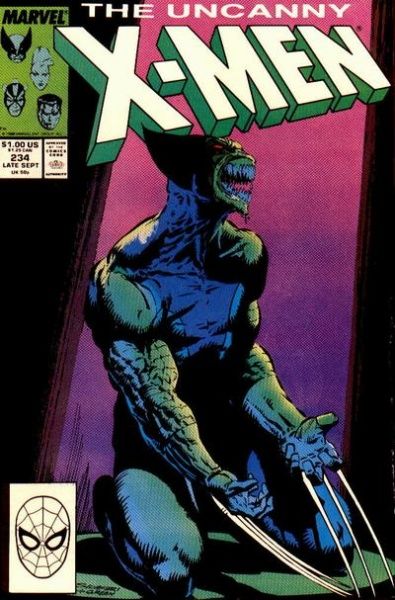

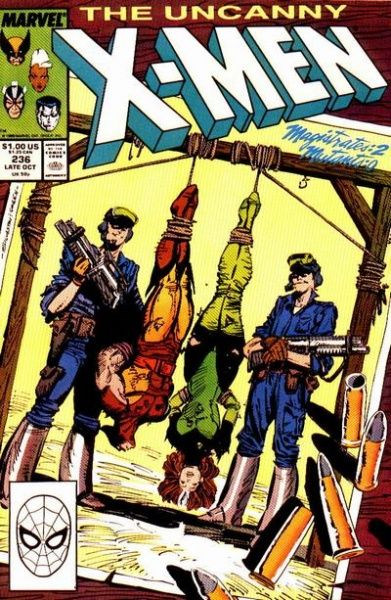

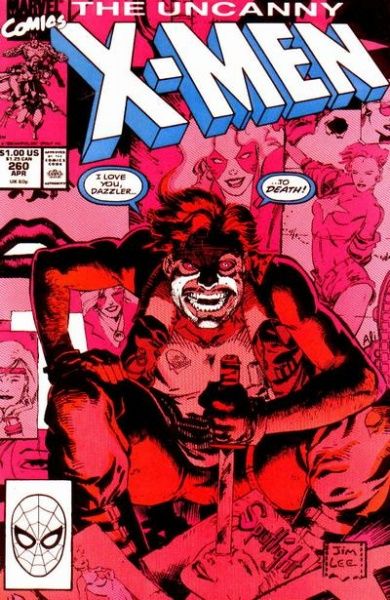

6. The Exile Era (Uncanny X-Men #229-245; May 1988-June 1989). After they "died," the X-Men became invisible to any electronic scanning devices. I wonder if that's ever brought up these days? (Considering that many of them are inhabiting new bodies - sigh - it might not be relevant, but I think Logan and Alex, and maybe Alison and Longshot,ought to still be able to skulk around without setting cameras off.) They decided to zip around the world using an abandoned Outback town as their headquarters and the bullroarer-spinning character find of 1988, Gateway, to teleport them where they needed to go! This era was brief, as there's not much you can do with this kind of set-up, although we did get a nice Brood story that introduced a sympathetic preacher, William Conover (I know, a sympathetic preacher in a comic book!), and the first Genosha story, which was pretty darned good, if you ask me. Then it was time for Inferno, which sucked, and the X-Men couldn't really keep pretending that they were dead, considering all the other mutants saw them. This era ended with issues #244 and 245, the first of which introduced Jubilee to the world (Jubilee is awesome, by the way) and the second of which poked fun at DC's "Invasion!" crossover. It featured art by some guy named Rob Liefeld - I wonder whatever happened to him? These two issues might be the last time one of the two main X-titles were actually something less than serious. They're pretty funny, actually. 20 years of grimness followed!

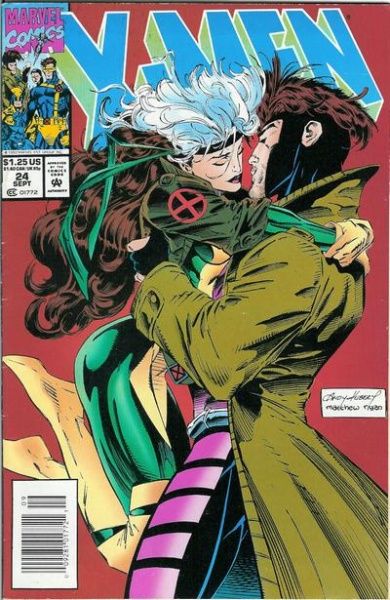

7. The "Things Fall Apart" Era Mark 2 (Uncanny X-Men #246-269; July 1989-October 1990). After the brief caesura of pseudo-stability in the Exile Era, Claremont brought back Nimrod and proceeded to rip the team apart again, except this time he made sure it stuck! This is one of the saddest periods in X-history, because we've been through so much with these characters (even the new ones) and Claremont really puts them through the wringer, and even though we know none of them die, it's still a gut-wrenching group of comics. First Rogue goes through the Siege Perilous, the weird cosmic gate that Roma gave the team during the "Fall of the Mutants." She's sucked in when they trap Nimrod in it, as it's the only way to stop him. The Siege Perilous doesn't kill a person, but it does wipe their memories and recycle them back into the world. Then Havok accidentally kills Storm as he tries to save her from Nanny and the Orphan Maker (well, not really, but we all thought so). Then Wolverine disappears on one of his solo jaunts (remember when that mattered, keeping track of Logan while he starred in two books?). Then Donald Peirce shows up with his Reavers to kill them all. Psylockegets the rest of the team to go through the Siege Perilous, Wolverine gets captured by Pierce and nailed to a cross, and Jubilee, who's been hiding in the town, has to rescue him. For a year there was no real team, which is pretty astonishing when you think about it. Logan and Jubilee went searching for the X-Men, finding Psylocke in the body of an Asian ninja (sigh) and hooking up with the Black Widow for an issue. Meanwhile, the patients at Moira's research station fought Mystique and Freedom Force and then Pierce and his Reavers, while Storm, who had been turned into a child, regressed to a life of crime along the Mississippi, eventually meeting Remy LeBeau, who quickly turned into the worst character ever. These issues were coming out twice a month for quite a while (17 issues are cover-dated 1989, while 15 are cover-dated 1990), so Claremont packed a ton of stuff into them. This is not an era as fondly remembered by the general public as it is by your humble chronicler, as I consider it fine stuff. Issue #269, which ended this era, features Rogue fighting the corpse of Ms. Marvel (not really, but sort of). It's a pretty good issue, but I always wished Rogue's personality split was resolved a bit better. I suppose for 1990 that was as subtle as we were going to get (the two sides of her mind become real and they fight!), but it was a bit frustrating. Remember that issue when she went to see Michael Rossi and didn't realize Carol Danvers knew him,but Rogue didn't? Powerful stuff. But Claremont couldn't do much more, because it was time for the next era to begin with ... a crossover!

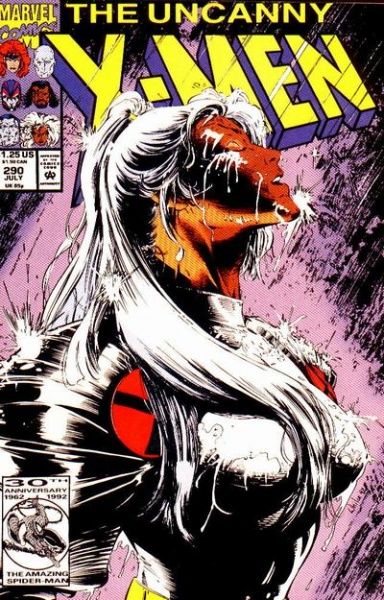

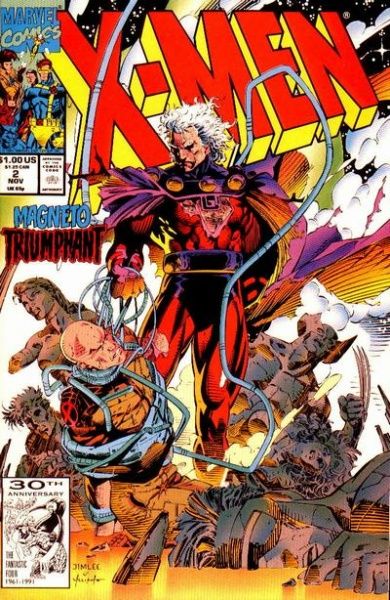

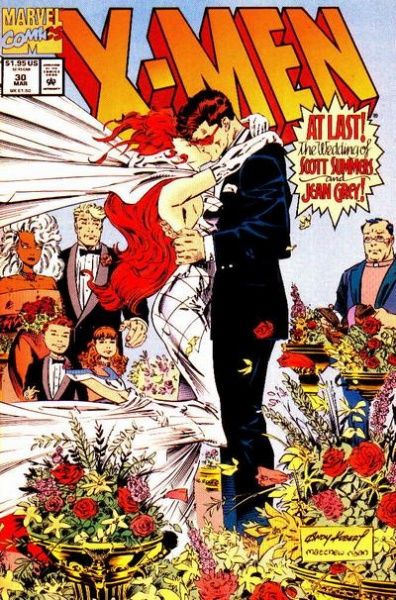

8. The Rebirth Era (Uncanny X-Men #270-296; November 1990-January 1993; X-Men #1-16; October 1991-January 1993). In the middle of this era, Claremont left the book, which ought to signal the end of an era, shouldn't it? But it didn't, because the succeeding writers (Scott Lobdell and Fabien Nicieza, for the most part) continued the themes of what Claremont had done for a while after he left. Issue #270 began the big Genosha/Cameron Hodge crossover, which was pretty awful, and then Claremont decided to bring Xavier back. Personally, getting rid of Xavier for five years or so was a great idea and should have lasted much longer, like to the present day, but the story wasn't bad (and involved a Skrull replacing heroes - what a radical concept!) and got everyone back together. Then we had the Shadow King story, which set the stage for the new teams and the new book, thefirst issue of which is still, I think, the best-selling comic ever (yes, I bought all five covers, because I suck). The Rebirth Era lasted through the introduction of Bishop and Mikhail (and those absolutely brilliant issues #289-290, where Forge asks Storm to marry him and gets shot down), Magneto going all evil again, a Longshot appearance, and ended with that godawful "X-Cutioner's Song" crossover (so many crossovers, so little goodness). It wasn't a great era, but it did give the franchise a jolt, especially because Claremont, obviously, was rushing through some things and may or may not have been able to do what he wanted. Unfortunately, at about this time, the X-Men as they stood had enough of a history that it was able to be mined more and more. When Claremont did it, it was less egregious because he had created a lot of the characters and we hadn't gotten too sick of them yet. But as often happens with a long-running series, the reappearance of old characters becomes an exercise in nostalgia with an emphasis on the "coolness" factor and not on the relevance to the story. This began to happen more and more in the X-books, and that's where we find our next era.

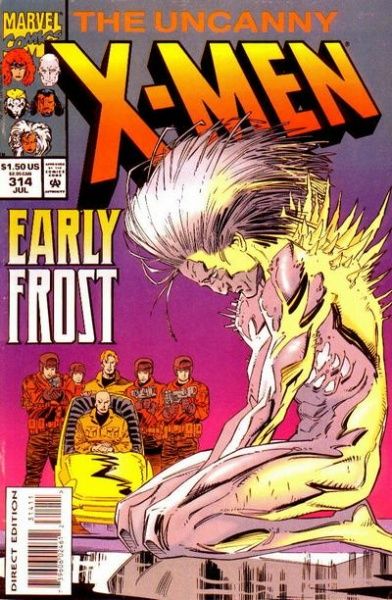

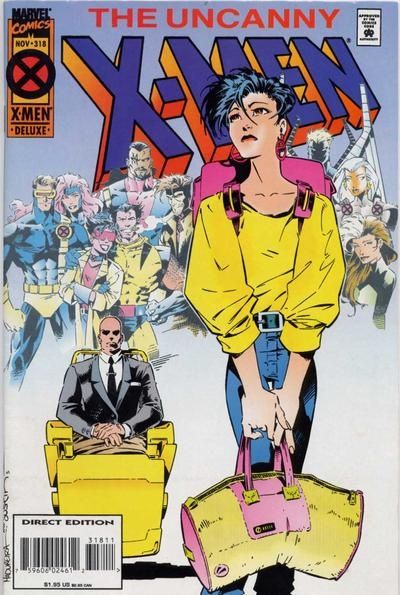

9. The Legacy Era (Uncanny X-Men #297-321; February 1993-February 1995; X-Men #17-41; February 1993-February 1995). Uncanny X-Men #297, in which Xavier can walk again, briefly, and has a heart-to-heart with Jubilee, is a great issue. Lobdell was not a bad writer of the title, although he was hampered, as most mainstream superhero writers were in those days, by the necessities of the corporate structure. His run is not terribly memorable, but occasionally his writing rose above the subject matter. Nicieza wasn't as good on the junior title, but to be honest, he was stuck with Psylocke and Revanche, which is possibly the worst storyline in X-history (I smell another list post!). The reason this is the Legacy Era is because during this time, the writers did a lot of historical stripmining, with new characters (the Acolytes) getting stapled onto existing stories. There wasn't a whole lot of innovation in this brief era, although Uncanny X-Men #314, in which Emma takes control of Bobby's body and goes searching for the Hellions, is another great Lobdell issue and begins Emma's long road to redemption. The Generation X crossover ("The Phalanx Covenant") is in the heart of this era, because Marvel realized they needed New Mutants! Let's get some more young'uns! And then Marvel went and killed Professor Xavier. That pretty much signals the end of an era, doesn't it?

10. The Onslaught Era (Uncanny X-Men #322-337; July 1995-October 1996; X-Men #42-57; July 1995-October 1996). The height of excess in the 1990s is the Onslaught Era, which you might think is the low point of Mutantcy. Of course, you might disagree and love this era. It begins after the weird four-month Age of Apocalypse. After Xavier's "return," the era starts well, with Juggernaut getting punched across half the continent by something called Onslaught. Oh, Onslaught. Such potential. Such a waste.Then we got Gene Nation, which also could have been cool but wasn't. And Psylocke fought Sabretooth again, and it wasn't as good as the first time. C'est la vie. And thenthe Onslaught story really kicked in, and not only was the payoff not terribly good, the execution was muddled. It was a real shame, because with better writers, it might have worked. Emphasis on "might," of course. As this was the time in comics that people really think of when they say "The Nineties sucked," there was more spectacle and obnoxious rhetoric and art than we had seen even when Claremont was being Claremontiest, and I can't even imagine reading these issues and trying to make sense of them. But at least it had a focus, which is more than we can say for the next era.

11. The Loss Of Focus Era (Uncanny X-Men #338-393; November 1996-May 2001; X-Men #58-113; November 1996-June 2001). The late Nineties were not kind to the X-franchise, nor to mainstream superhero comics in general. The speculator bubble burst, and although there was plenty of good stuff on the fringes, the main titles of Marvel, especially, were marked by some really awful storytelling. DC managed to escape it a bit better than Marvel did, but it was still a pretty lousy time to read mainstream comics. This era of the X-books certainly isn't lacking in attempts at grand stories, but creator turnover and messy plotting meant that the books could gain no real continuity, and whenever something happened that might have some potential, it got lost in a crossover miasma and often relegated to the lesser titles of the franchise or even "special" issues. I'm thinking mainly of Operation: Zero Tolerance, which could have been a really neat storyline but got diffused over the line and fell apart because of lack of communication between editors and creators (or so I assume - maybe everyone really was inept!). It's a shame, because the creators at this time weren't awful. Steven Seagle and Chris Bachalo teamed up for a few decent issues in an otherwise forgettable run, and the introduction of the "new" X-Men ("The Hunt for Xavier," issues #362-364 and #82-84)was a neat idea that turned to crap quickly. Alan Davis coming onto both books as writer and artist seemed like a good idea, but it wasn't, as the X-Men wandered through time and space for a while with, not surprisingly, no focus. Late in this era (in 2000), Claremont came back, but that didn't help either, as he brought in new characters that weren't very interesting (a problem earlier this era with the introduction of Marrow, Maggott, and Cecelia Reyes) and went off with his new pet themes, which revolve around slavers a lot. Weird. At the very end of this run, Colossus sacrificed his life to help spread the cure for the Legacy Virus and the X-Men went to Genosha to defeat, yet again, Magneto. Both of these stories typify the mess the franchise had become - not-bad ideas, but truly horrible execution. The time had come for Bill Jemas to shake things up, because that's what the X-books desperately needed.

12. The Joe Casey Era (Uncanny X-Men #394-409; June 2001-September 2002). In the middle of 2001, the X-books got a huge boost when Grant Morrison came on board as writer of the adjectiveless book (which I will never refer to as "New X-Men." At the same time, Joe Casey, who was less of a name but is still very talented, took over Uncanny for a rather odd year. This is when we need to start separating the two titles, because prior to this, they were often intertwined and the eras ran somewhat concurrently. But Casey was certainly a different kind of writer than his successor, so we can't place him in with Austen. His run was not received very well, partly because the first few issues were pencilled by Ian Churchill, who is not a particularly good artist. Casey also never seemed to really get a hold of what he wanted to do with the book. Did he want to make comments about pop culture, as "Poptopia" and the introduction of Stacy X seemed to indicate? Did he want to explore the mutant phenomenon outside of the United States, as we see in, again, "Poptopia" and Sean's X-Corps group? Did he want to try out some ideas that he later used to better effect in Wildcats 3.0, namely the attempts by superheroes to use corporate strategies? It's not clear what he wanted to do, and that's why this is a strange little era before the DarkAge of Uncanny X-Men. Casey doesn't seem to fit with standard superhero books, and he's not as weird as Morrison, so his run comes off as Morrison-lite, which is a shame because there were some interesting ideas, and at least, after the years of muddled stories, the issues were straightforward enough. It's just that Casey didn't seem to know what he wanted to do.

13. The God of All Comics Era (X-Men #114-154; July 2001-June 2004). Some would consider this the Golden Age of the X-Men. Others think Morrison took the team too far away from their roots, but that's really not true. Looked at as a whole, this is a fairly conventional X-Men storyline, albeit one marked by Morrison's hyperactive writing style and somewhat bizarre ideas. Morrison basically made it "cool" to be a mutant, especially among young people, which is only logical, if you think about it. He ran with this idea for some time, but never really got the most out of it that he could have. What Morrison really did for the X-books is provide it with some much-needed "buzz" and some very strong stories unfettered by crossovers and interaction with the rest of the Marvel Universe. Those things can be strengths, of course, but in the late 1990s, they became glaring weaknesses in not only the X-franchise but in the Marvel U. in general. So Morrison really went "back to basics" with the X-Men, writing stories that appealed to the long-time fans (even though some of them complained) but had a modern twist on them. Some of his ideas were simply marvelous - destroying Genosha and killing (or so we thought) Magneto; giving Xavier and evil twin; making Wolvering Weapon Ten instead of Weapon X (I didn't actually like that one, but it was certainly different); making the school a school again. He also wrecked the Scott-Jean relationship by having Scott commit mental adultery with Emma. His run is full of dense issues that, in the best Claremontian tradition, all lead to some big pay-offs at the end of the run. You may not agree with some of the roads he went down (I never liked making Scott cheat), but his era made the X-Men relevant again and gave future writers some fascinating places to go. Of course, they largely ignored them or went to the less interesting places instead of the good ones, but that's not Morrison's fault, is it?

14. The Dark Age a.k.a. The Chuck Austen Era (Uncanny X-Men #410-443; October 2002-June 2004; X-Men #155-164; June 2004-January 2005). In issue #410, Chuck Austen took over the flagship title of the X-franchise and soon proved that he had no idea how to writea decent story. Actually, that's not necessarily true, as the set-ups for his arcs often promised good stories (at least early in his run) that he just couldn't pull off. It all started to go horribly wrong with the "Draco" arc (issues #428-433), which was as wrong-headed a story as you can ever find in an X-Men comic. Even prior to that arc, Austen was proving he couldn't really follow through, but that was the one that was puzzling from the very beginning and had no potential whatsoever. This erawas also when Marvel decided to "manga-ize" the main book, which led to some awful, awful art by a succession of artists. Not only were Austen's stories insipid, but his characterization was terrible too. I should have dropped the book when Warren started boinking Paige, but I didn't. The only memorable thing from his run for me was Juggernaut's relationship with Sammy, which was actually sweet and kind of interesting. For all the good work Morrison did on X-Men, Austen almost undid it on Uncanny X-Men. It's really astonishing how bad these comics are. Even when the X-books had no focus, they were better than these. That's just sad.

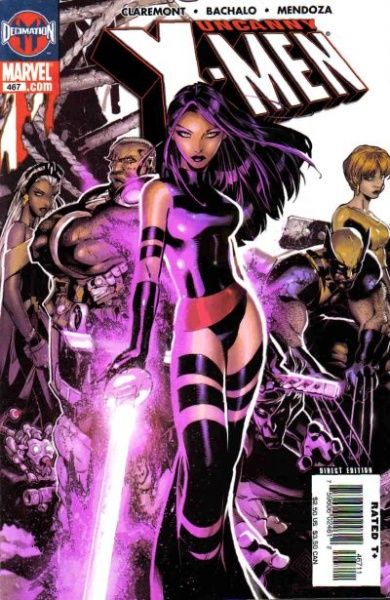

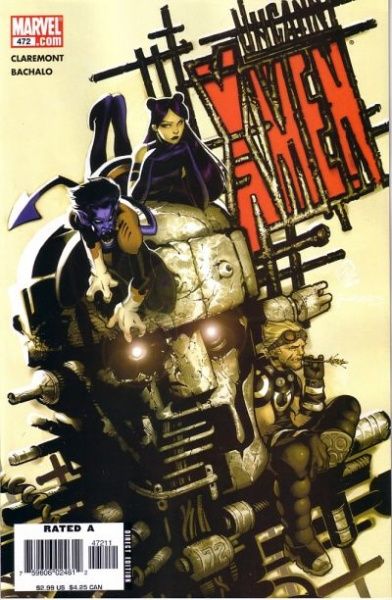

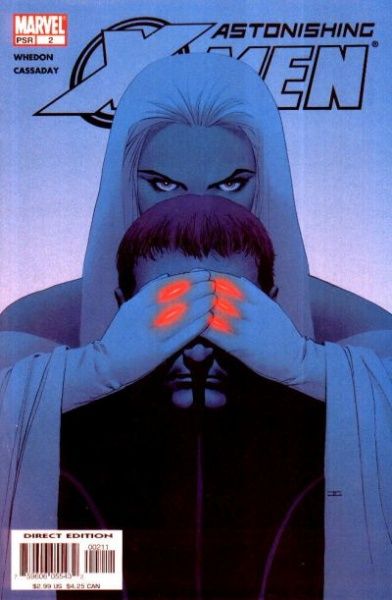

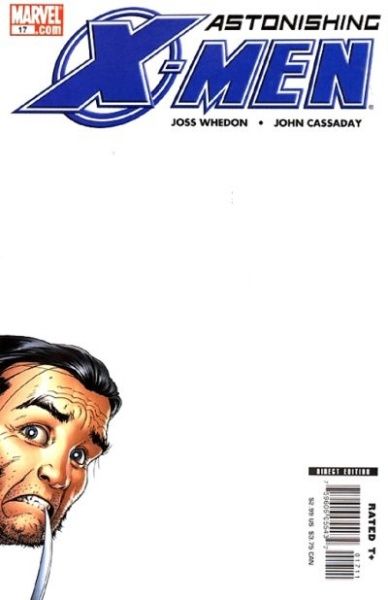

15. The "We Screwed Up; Let's Pander To The Old-Timers" Era (Uncanny X-Men #444-474; July 2004-August 2006; X-Men #165; February 2005; Astonishing X-Men #1-24; July 2004-current). Following the two-headed monster of a) the seemingly far-too-weird Grant Morrison; and b) the suck-fest of Chuck Austen, Marvel decided to bring back Chris Claremont on the main title (his pet title, X-treme X-Men, was apparently not "extreme" enough!) and simply let him pretend the past 15 years had never happened. That's probably not fair, as this is the only extended run on either title that I haven't read (except for the original issues from the Sixties), but it's Claremont and Alan Davis doing Savage Land and Rachel Grey stories and bringing Psylocke back from the dead. What am I supposed to think? I have read a few of these issues, and I really liked Uncanny X-Men #467 (the one that takes place in 24 seconds), but I doubt if this era, at least on the main book, is really that memorable. At the same time, however, Marvel launched Joss Whedon and John Cassaday's pet project, and although it's been over three years, only 23 issues have appeared, so that part of the era is still going on. You may detect a note of scorn in the naming of this era, but I don't really mean it all that much. Astonishing, from what I've read, is a perfectly competent comic, but Whedon really seems to be trying to recreate the "Superhero Era" of the X-Men, and that may or may not be a good thing. Even if you love the book (and many do), I don't think you can claim it's a very forward-looking comic and I don't think you can deny that it's not trying to be something from the "Golden Age" of the X-books. Again, that's perfectly fine, but that's also why, in the aftermath of a pretty experimental phase of X-history, this is pandering to the old-timers.

16. The Attempted Weirdification of the Mutants Era(X-Men #166-187; March 2005-August 2006). Meanwhile, over on X-Men, Marvel brought in Peter Milligan in an attempt to recapture the somewhat off-kilter sensibility that Morrison gave to the book. Hey, it worked on Animal Man, man! This didn't work as well, as Milligan teetered between "good" Milligan and "bad" Milligan for most of the run, giving us some very weird story ideas but ultimately falling back into a predictable pattern. Milligan is too good a writer to fall as far as Austen, but his 22 issues are notable mainly for Salvador Larroca's changing art style and Milligan's attempts to be bizarre within the framework of the greater story. His characterization, which is often the strongest part of his writing, is easily the most interesting part of the run, and, like Austen, some of his plots had promise (the first one, about something mysterious called "Golgotha," gave me high hopes that were cruelly dashed). He ended the run with a odd Apocalypse tale that showed the strengths and weaknesses of the whole: an interesting take on an overused and somewhat boring villain; a revamping of Gambit and Sunfire; and the X-Men basically acting petulantly and not really working together all that well. It too failed, but at least Milligan's run was an interesting failure as opposed to an excruciating one.

17. TheMeat-and-Potatoes Writers'Era (Uncanny X-Men #475-current; September 2006-current; X-Men #188-current; September 2006-current). With Claremont shunted aside again and Milligan off to DC, Marvel turned to Ed Brubaker and Mike Carey, two very solid writers, to right the ships again. This era hasn't been going on long enough for me to really give it a good name, and I could easily put Whedon's Astonishing X-Men in here, as it shares many of the characteristics of the two main titles. Brubaker, who is much better at noir fiction than superheroes (that's not to say he can't write straight-up superheroes, just that he's not as good at it), threw the X-Men into space for 12 issues to deal with his pet character, Vulcan, the third Summers brother. You might think this is pandering to the old-timers, but the Emperor Vulcan story is more an attempt to build on the past rather than recreate it, and I'm still not sure what the point was, because with his second story arc, Brubaker made the X-Men far more like his other mainstream Marvel books, notably Daredevil and Captain America, in that he stripped away a lot of the flash and made them much more gritty. Meanwhile, in the sister title, Carey and Chris Bachalo/Humberto Ramos decided to go with a balls-to-the-wall action-adventure, and so far, it's working pretty well. Carey is also mining the past a bit, but in less of a reverential way than Whedon is doing. The reason I named this era the "Meat-and-Potatoes Writers' Era" is because the art has been nothing spectacular (Bachalo's has occasionally shown the brilliance of his early career, but other than that, the artist have just been doing a solid job) and the two writers appear to have nice long storylines in mind without a lot of bells and whistles. Of course, right now they're in the middle of a crossover, so we'll see what happens going forward from that.

Wow. That's a lot of eras. I suppose a book that hasbeen around for 44years will go through a lot of changes. So which is your favorite era? Here's an idea: I want you to rank them. Give me your five favorite eras, 1 to 5. I will assign point totals to your selections and then add them all up. Soon we will know which is the favorite X-Era!

Let's give you the Thanksgiving weekend for the vote. Even if you're not celebrating Thanksgiving because you live in one of those pinko countries that don't celebrate it, you have until the end of the day on Sunday to vote. How's that sound?

Go now to the comments and vote! And tell us all why you love those eras so darned much. Defend your love of Chuck Austen!