For more than four decades, Walt Simonson has been writing and drawing comics. He first made a name for himself as an artist on the "Detective Comics" backup series "Manhunter," shifting from project to project before exploding as a superstar talent on "Thor." He adapted the first "Alien" movie and drew "Robocop vs The Terminator" from Frank Miller's script. Known as both a writer and artist, he's collaborated with everyone from Archie Goodwin to Jon J Muth, from John Buscema to his own wife -- a comics legend in her own right -- Louise "Weezie" Simonson.

In recent years, Simonson's work has re-entered the comics spotlight. In addition to his current series "Ragnarok," which he's writing and drawing at IDW, much of his classic work has been reprinted, with multiple "Artist's Editions" and "remastered" volumes introducing his classic work to an all-new audience. Taken as a whole, they represent his career path, moving from one project and genre to the next, which has served as an inspiration and a model for an entire generation of creators.

CBR News: Your career and the path you've taken in many ways seems to be the model for what a lot of artists are trying to do today.

Walter Simonson: Now you're scaring me. [Laughs]

When I say that, I mean that you wrote and drew "Thor" and "Fantastic Four," you wrote "The Avengers" and drew "X-Factor." You drew "Manhunter" and "Elric" and wrote and drew "Star Slammers" and "The Judas Coin." You jump between creator-owned projects and licensed projects, working in different genres at different companies. How much of this was planned?

I'd like to say, "Oh, my career was totally planned!" But really, I'm more like a bee. I go from flower to flower. Some of it is the changing times -- comics thirty years ago were a different business than what they are now. Some of the stuff I did in the old days probably reflected that more. I don't keep track of modern comics that carefully. I've said before, the only book I look at regularly is "Usagi Yojimbo" by Stan Sakai. I have the impression -- which may be incorrect -- that with few exceptions, there aren't a lot of artists and maybe writers as well who are on books for a long period of time. The artists I'm familiar with, guys like Leinil Yu -- I don't follow his career that closely, but he seems to be asked to do four to five issues of some book that's starting out, and then he's moved over here to do a few issues of this and a few issues of that. A lot of artists seem to be moved around -- or move themselves around. That's not what I wanted to do, at least initially.

In the old days, once you were on a book regularly, you were on that book until either you ran out of gas on it or the editorial situation changed and a new editor came on. Go back to the '60s, and how many issues of the "Justice League" did Dick Dillin do? Over one hundred. [Jack] Kirby was on books like "Fantastic Four" for over one hundred [issues]. That seems to not be the model any longer, but in my early career, it was, partly.

"Manhunter" was a short run, largely because it was a bimonthly backup in "Detective Comics," and after we reached Chapter 5, Archie was hired away from DC to go back to Warren. The new editor was Julie Schwartz, and he did not want to run a "Manhunter" backup. If Archie had stayed on at DC, I expect that we would have kept doing "Manhunter" for at least a little while longer. We didn't start it with the idea of making it a complete story cycle. With Chapter 5, because we knew that Archie was leaving and the feature was ending, we thought it would be cool to do the whole thing as a complete unit.

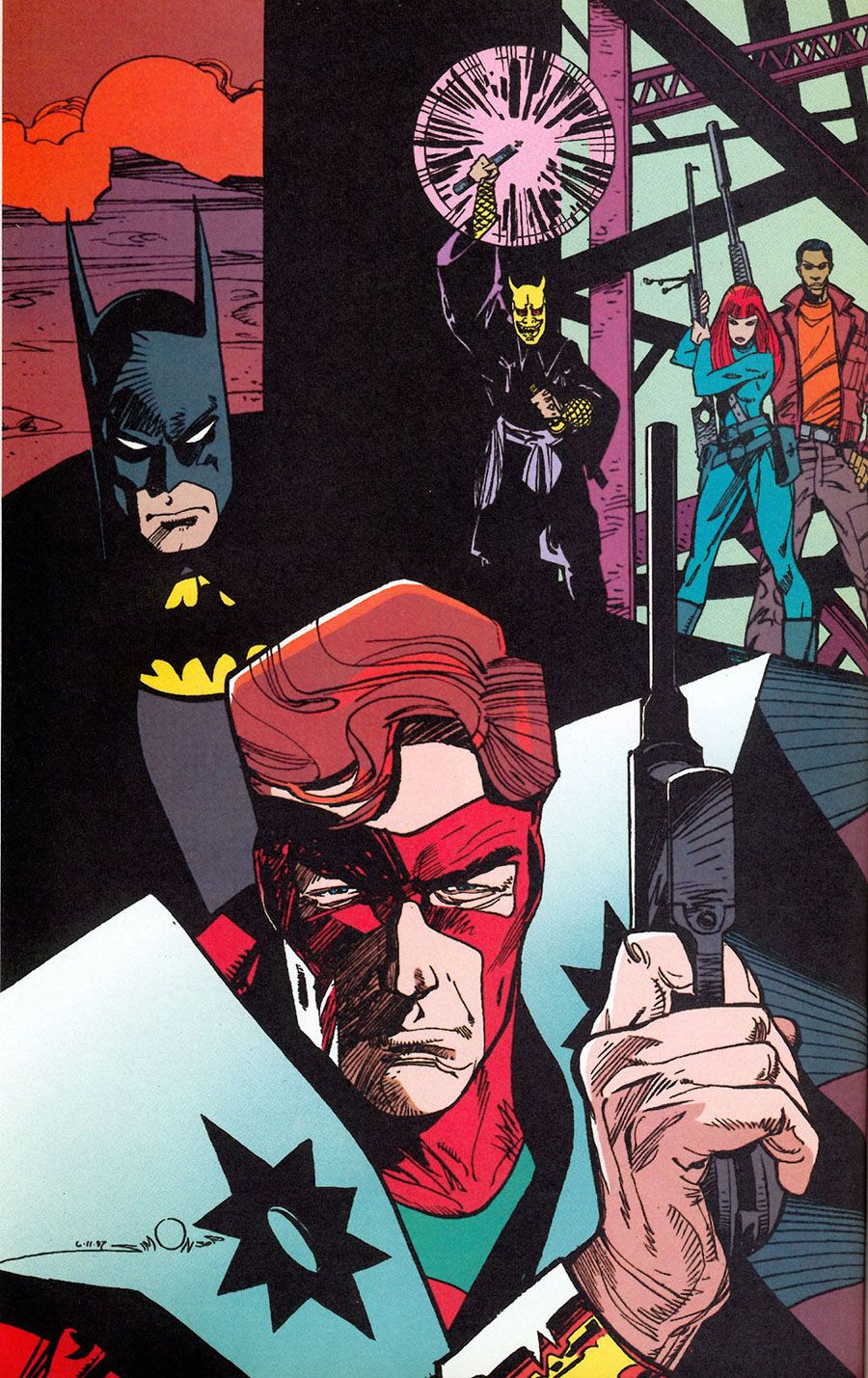

We had talked about doing a crossover at some point with Batman, because Batman was the lead feature in "Detective Comics." As a result, we decided to use that story as the finale because that gave us 20 pages. "Manhunter" was an eight page feature, so that gave us a longer story and it gave us Batman and it worked out pretty well. We did it because it was fun and we thought it would be cool. I don't think we thought of it as any kind of groundbreaking deal. It was just something that seemed appropriate for the character. Given his tragic background, it seemed an appropriate way to do things.

So it wasn't a plan on your part.

A lot of what I've done over the year has been serendipitous. I think the one thing I've probably tried to do deliberately -- and this isn't like a five year plan or something where I thought really far ahead about how it was going to work -- but I did not want to do the same thing all the time. I didn't want to end up just doing superheroes or just doing science fiction or just doing fantasy. I had a lesson early on -- before I got into comics, I was at the Rhode Island School of Design, and while I was there, Carmine Infantino came to Brown University to give a talk. Brown is just up the hill from RISD, so I went to see him. At the end of the talk he had a Q&A session, and I was able to ask him a question. There was a book running at the time called "Weird Western Tales." They had a feature, El Diablo, who was a Zorro-type guy with a supernatural touch. I really enjoyed the strip. I thought there was a swashbuckling romance to what Gray [Morrow] did in that book that made the character sing.

Then an issue came out, and it was drawn by Alfredo Alcala. I like Alfredo's work a lot, but he has a very different sensibility. I asked Carmine why Gray was off the book, and was he going to come back and do more stories. Carmine's answer was that he felt that Gray was really more suited to science fiction stories, so he moved him off El Diablo and was going to use him for more science fiction work. I was flabbergasted. I'm a Carmine fan, but I was floored by the answer. It was my introduction to the idea that as an artist in comics, you could get typed. I don't think I thought of it quite this clearly at the time, but that's what I understood. I was surprised because I thought Gray was so good at that strip and I thought the work that came after him, while interesting, just did not have that swashbuckling romance that I thought seemed to really be appropriate for the character. That was my earliest lesson that you don't want to get typed as a certain kind of artist.

You were consciously trying to avoid that from the beginning, then, as best you could.

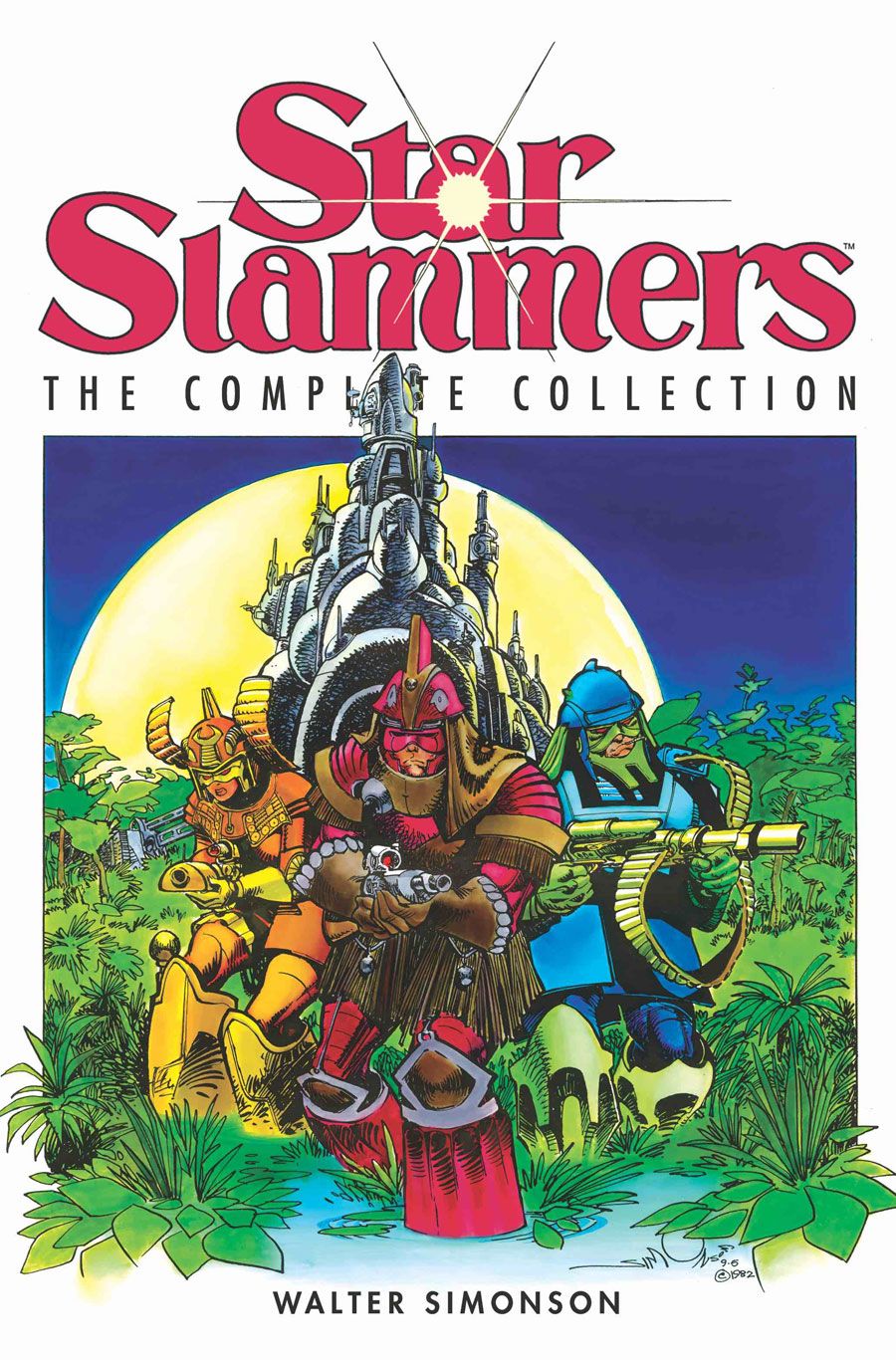

Most know my work from "Thor" or "Manhunter," so there are those who think of me as a superhero artist -- or an energetic artist. I try to put a lot of energy into the work. That's my legacy from Jack Kirby -- but Jack did a lot of different things, too. My samples to get into comics was a strip I did called "Star Slammers." That was my degree project at RISD, a comic that I'd written and penciled and inked and lettered. I brought that as my portfolio when I came to New York. My initial response from editors was, this is nice, what else can you do? What that meant really was, "I don't look at this stuff and see you doing Superman or Spider-Man." There were still war books and romance titles, but the superhero books were really taking over the market. I was green enough at the time -- I was very young -- I thought, well it shows that I can storytell, it shows that I can draw, how much more do I need? Of course, looking back, I can see I needed a lot.

I didn't get any work out of it at first, but I ended up, by accident really, in Carmine's office. I'd gone to DC to show my portfolio and I did not have an appointment with Carmine, but he ended looking at my work. He made sure I got some work, and I walked out of his office with three short stories to draw. Back then, a lot of us who were starting out did backup stories at DC. It was a good place to make a few bucks, stay alive, rent an apartment in Brooklyn or wherever, and learn your craft in a way that these days you do elsewhere. I was very aware that I was getting science fiction stories -- and I was not as good as Gray Morrow, I hasten to say. But I understood that I did not want to end up being typed as a science fiction artist, so I worked pretty hard to try and generate other kinds of jobs. We're talking short stories that are like six pages long. Back then, you really paid some dues to do that stuff.

How did you make the jump from that stage of your career to working on "Manhunter?"

Archie was an editor at DC at the time and gave me a few SF stories, and then he gave me a three-page story about a real event that had happened at the Alamo. I look back at it, and it's not my best work, but I worked my ass off on it. I was drawing horses and buckskin and adobe buildings. I read a whole paperback book on the siege of the Alamo for this three-page story.

I did not appreciate the significance of that job until years later when Archie mentioned it to me. Archie had been given "Detective Comics," and he wanted to do a new backup story. The Alamo job convinced Archie that I could draw stories other than SF. He had come up with the idea of a back-up feature named "Manhunter" and he offered me the strip to draw. "Manhunter" really was an adventure strip. It wasn't quite superheroes. It was set in different locations around the world. He was trying to create something that was in contrast to Batman.

The strip made me, professionally. The series won six Shazam awards from a group called the Academy of Comic Book Arts. What that meant was, I was better known by the time that strip was over and I had offers of work. I wasn't out pounding the pavement the way I had been before, haunting the halls of DC, talking to friends of mine looking for jobs. After "Manhunter," I was offered work regularly, and a lot of it I took. It was mostly stuff I wanted to do. I wanted to do comics.

While I haven't worked really hard to do every kind of story in comics, I have worked to not do the same thing all the time. I did superheroes because that was the market, and I really enjoyed superheroes. But occasionally, stuff would come along and I'd have a shot at doing fantasy or science fiction. I read a lot of science fiction when I was young. Not so much now, but I knew all the classics. When I got into the business -- as Neal Adams almost never fails to remind me when I see him -- I told Neal I thought I'd be in comics four or five years and then get a real job. I thought I would have learned everything I needed to know of comics, then I'd be off doing something else. I was young, what did I know? Here I am, more than forty years later. I'm still doing comics, and I still haven't figured it out. I figure if I keep working, I'll figure it out someday.

People may think of you as one kind of artist, but you were always conscious of not doing just one thing.

I did superhero stuff because that was the main market, but I found other stuff to do here and there. I don't know how obvious it is in my work, but I was an illustration major at RISD. I did not go there with the idea of doing comics -- I really came to that idea while I was at RISD. The head of illustration art back then was Tom Sgouros. He died a couple years ago, but he became a close friend and mentor. The department taught the idea of illustration as problem solving. You were given an illustration to do and you were trying to figure out how to visualize an idea. I brought that to my comics. I mean, I always draw like me and whatever I'm doing, it's pretty recognizable, but I've worked hard in different times on different jobs to tease out from the job the way I'm going to tell that specific story.

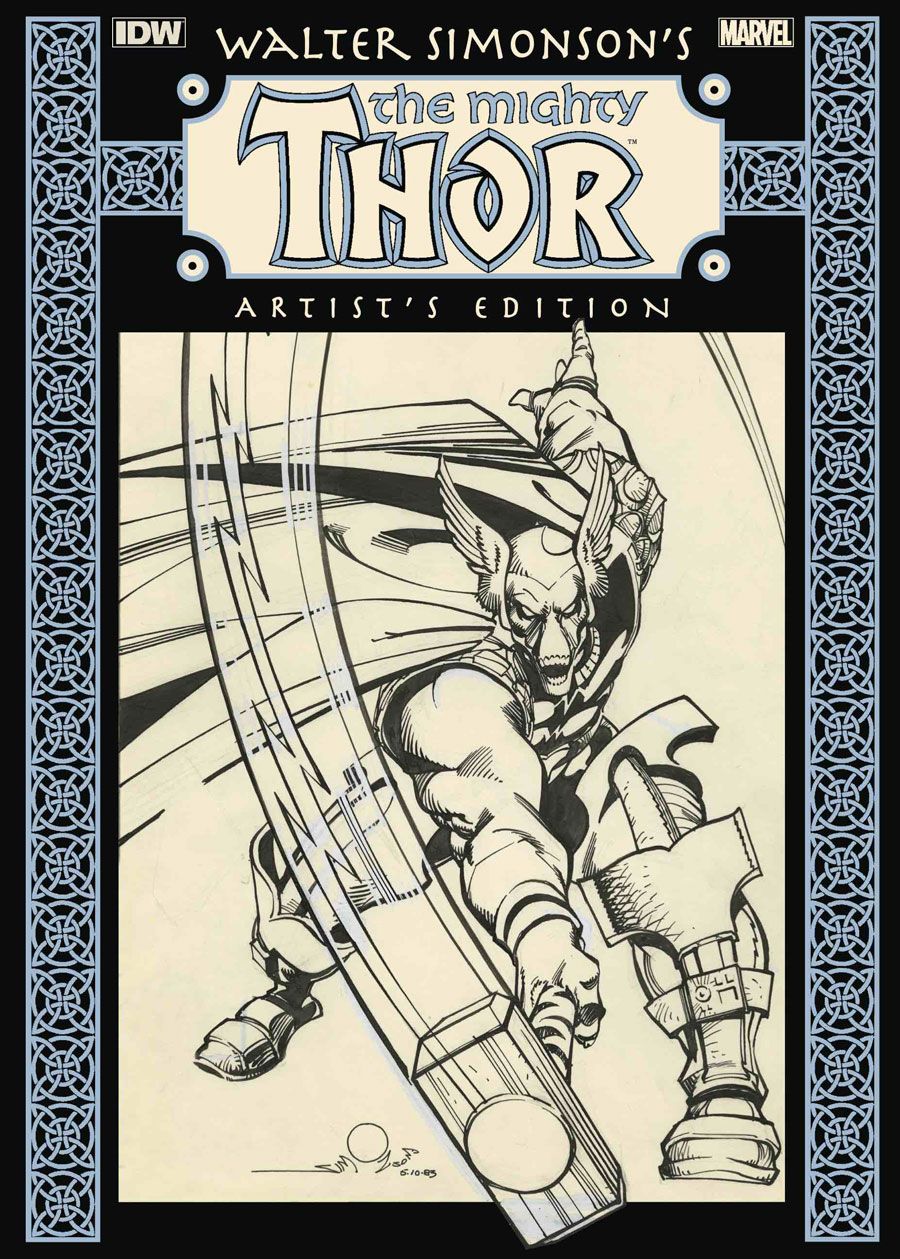

While I was doing "Thor" at Marvel, because it was mythological, it looked back to the past. I took a couple of mythology courses, but I remember one about mythology and philosophy and the change in Greece from the mythological view of the world to a more philosophical one. I was looking back to this mythological past, and that, to me, had a certain conservative quality, graphically. In that book, it's not six panel grids, but there's very little breaking out the panels, very little overlap, very little fancy graphics in the drawing or in the storytelling. It's pretty straightforward. I think when Lorelei is hypnotized by Fafnir, I did some little inset things that got smaller and smaller -- and that's about as elaborate as I got.

"Fantastic Four" had always been a book with pulp science fiction affinities, and it looked to the future at a time when you could be optimistic about the future. This apocalyptic vision of the future has always been around, but some of that seems to have a wider currency in comics now. Back in those days, it seemed more like we could use technology to solve stuff, and Reed Richards was the guy to do it. In that book, I did a lot of elaborate graphics, fancy layouts, or more radical layouts. I had my own copier in the studio, so I did a bunch of art where I copied stuff and used the copies as a way of creating some graphics. There's a shot of Reed and the crew on a sled and a splash page in one of the early issues. It looks likes an overlay of one drawing on top of the second drawing. It's the same drawing, just offset by a sixteenth of an inch on the copier to create this double image.

I was thinking of "The Judas Coin," the DC graphic novel you wrote and drew a few years ago, where each story was told in a different style and approach.

The initial Roman Empire gladiator story -- not unlike "Thor" -- was a five or six panel grid, with a couple exceptions, but it's very conservative with the way it's approached visually. The last story, which was a science fiction story set in the future, I tried to draw it as if Walter Simonson were a manga artist. I'm not saying I am a manga artist, but I used some of the techniques of manga to approach that drawing and try to capture a feel that was different from the other stories.

For the Bat Lash story, I went back and shamelessly looked back at Nick Cardy's work, which is my favorite Bat Lash stuff. I used that as the basis for my work, but one thing that was Weezie's idea was, I also had them knock back the black plate on that job to a very dark brown, almost a sepia, so it looks like those old daguerreotypes after fading. It gives it a certain look that's not like the other stories. That was a book where I approached every story a little differently.

One of the things I've also done is, I have worked with a number of different people over the years. I didn't get into comics as a writer. Even though I'd written my degree project, I hadn't thought about that as a career move. Once I'd been in comics for a few years, I had a chance to work as a writer. Having learned an enormous amount from Archie and other collaborators, I took a crack at it and it seemed to work out okay. Since then, I've done work where I will deliberately take on a project where I am an artist and somebody else is the writer, or where I'm the writer and somebody else is the artist. Or I'll do work where I'm both the writer and the artist.

When you work with somebody else, whether as a writer or artist, they always have ideas you don't have. That means you have to create visuals that you wouldn't have thought of on your own, or you have to write in ways you may not have thought of. Around 1990, Weezie and I co-wrote a four issue book, "Meltdown," that Jon Muth and Kent Williams painted. It was a Havok/Wolverine story for Marvel, and it came out pretty well, I thought. Wolverine gets captured and a brainwashing helmet gets put on him -- I forget the details -- and I have to say that Kent painted that in a way I wouldn't have thought of in a million years, and it was just great. I don't know if our writing was different because of it, but I know if I was drawing it, it would never have looked like that.

Generally speaking, when you make the writing vs. drawing vs. writing and drawing decision, does it depend on the people, the project or if it's something you haven't done before?

Probably all that stuff, to different degrees on different projects. On "The Avengers," Mark Gruenwald was the editor and offered me the gig. It was John Buscema and Tom Palmer -- how could I not work with these guys? I knew John somewhat -- he had worked for Weezie when she was editing at Marvel. He was this gruff guy who was a fabulous human being and an astounding artist. He's one of my picks for the three best draftsman comics ever had. Garcia-Lopez is the second one, and I don't know who the third one would be. I always say three, but those two are my favorites. I can name a number of guys who draw beautifully, but John drew so beautifully and he could story tell beautifully. It was very conservative storytelling. He mostly did five or six panel pages. It was very straightforward, and yet it just flowed like buttah. [Laughs]

He was so gifted at that. I don't think he fully appreciated how good he was at that stuff. For the chance to work with those guys, I said, I'm totally in. This was right at the beginning of the time that Marvel editorial was starting to have more input about stories. When I'm doing stories, I like to play a long game. It's one of the reasons I'm not fit for the current superhero stuff, because there are so many crossovers and so much stuff comes down from up top. It's hard to plan long story arcs and have them reach fulfillment without a lot of interruptions. "Avengers" was the first time I ran into that. I would be doing a three-issue story and I'd be told in the middle of it, "This month Thor is not on Earth so you can't use him in 'The Avengers'" -- and I'd be in the middle of my story. That was a fictitious example; that's not one of the ones that actually happened, but that's what I ran into.

After I'd been on the book for about eleven months, I said, you know, this just isn't working out. All these characters were from other books, and you had to match course and speed with other books and other creators with whom you had very little contact and no control over the characters. I understand it, but I come from a time where Batman and Superman were together in "World's Finest," and it didn't matter what the heck Superman was doing in his own book, it didn't matter what Batman was doing in his book. So after eleven months, I went, "Okay, I think I'm done here. I just can't do the kinds of stories I want to be able to do."

Right as I was quitting, "Fantastic Four" opened up. Ralph Macchio, the editor, asked me if I wanted to write and draw "Fantastic Four," and because it didn't have characters from other books in it, and you could essentially do what you wanted, I said, sure. Oddly enough, I could borrow Thor and Iron Man and use them as I needed in the book for a sequence. Several of the "Avengers" stories I would have done, I turned them upside down and made them into "Fantastic Four" stories. The FF went their own way as well, it wasn't just recycled Avengers stories. It was funny. It hadn't worked out in the "Avengers," but I was able to do "Fantastic Four" for a bit and played a longer game and told the stories I wanted to tell. I'd wrapped everything up on "The Avengers," and I hadn't had to go out looking for work.

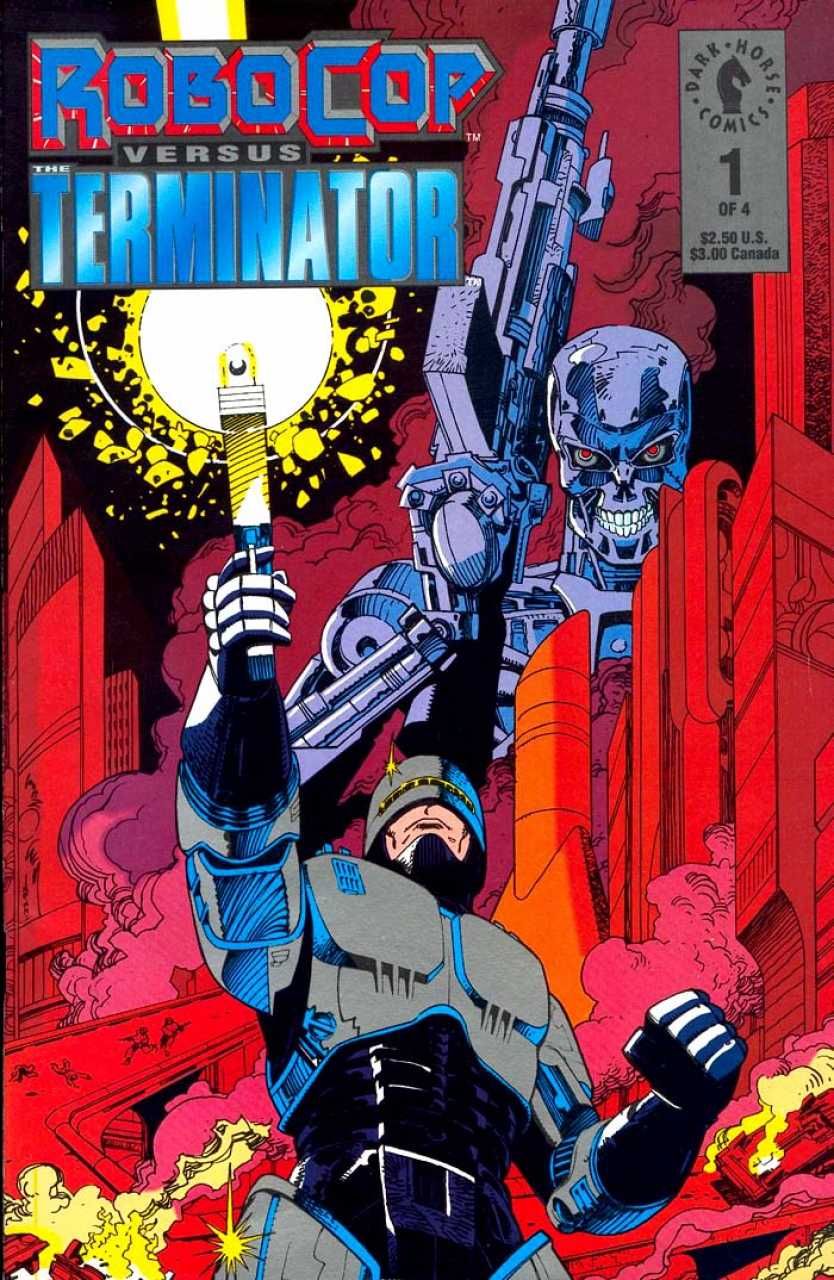

This is the serendipity of things. When I was wrapping up "Fantastic Four," I had been at Marvel for, I don't know, 17 years? Something like that. I decided, maybe it's time to do something else in comics. Literally as I was wrapping up "Fantastic Four," I get a call from Frank Miller. He was going to be doing a comic for Dark Horse, a four-issue limited series, "Robocop vs The Terminator." Would I be interested in drawing it? I couldn't get on that book fast enough. That came completely out of the blue. It was an offer I couldn't turn down.

"Ragnarök," the book I'm doing now that's my own version of the Norse myths, I'm really doing because about 16, 17 years ago, Scott Dunbier, who at the time was working for Wildstorm as the editor-in-chief when they were still an independent company, called me up out nowhere. Scott's an old pal. We go way back, and he asked if I'd be interested in doing my own creator-owned book on the Norse myths at some point. I said, sure, that sounds cool. I had other work to do, and I didn't finish the other work for about 15 years. [Laughs]

By the time I wrapped that up, I thought, maybe it's about time to think about that book for Scott. I'd had some ideas and had things worked out to where I had a basic idea for a story and characters. By that point, Scott was at IDW, he was three companies down the road. It worked out pretty well. He was all set to do it, and so was IDW. I couldn't have been more thrilled. I said I like to play a long game. It turned out okay. So far, so good.

In recent years, we've seen a lot of reprints of your work. Most notably in the Artists Editions, reprinting the original art at its actual size, but it's also possible to read "Star Slammers" and "Alien" and "Orion" and "Thor" and see the work you've done over the course of your career.

I lucked out in that I generally have not sold my artwork.

That goes back to the early days of comics. The first four years or so I was in the business was before companies were giving artwork back. I used to get photostats of the work I turned in so I could study it, try and figure out what I'd done wrong, how I could get better. I couldn't afford full size photostats back then. I'd get 80% photostats, I think. They were bigger than the printed size, but smaller than the originals. There was a stat house on 3rd Avenue where I got to know the guys pretty well. A couple of the guys that worked there -- I've forgotten their names now -- but when they saw me coming, they knew what I was looking for and were very obliging. About four years into my career, DC and then Marvel began giving back artwork. They went through all the closets, and in the end I got back almost all of the art I had done. There's still one Manhunter job that disappeared. There's no way to know what happened to all the story, but I got most of my stuff back. I liked studying it and going, "Boy, I didn't get that head right," or, "I can see this eye is incorrect," or, "This is a terrible horse." Back then, comics printing was really awful. Blacks were very gray, and my fine line work would drop out. They went to some flexographic press in the '80s, and that was worse, if anything. So studying the originals was very helpful to me.

I'm always amused by the discussions I see about new coloring vs old on existing material like the "Thor Omnibus." Whether you like the old coloring better or new coloring, one of the things I never see in those discussions is an awareness of how much more of the art can be seen in the modern edition that you can't see in the old printing. The blacks are solid, and linework that dropped out is now clearly visible. I do understand that it's possible to screw up work now in a way that was never possible in the old days. It used to be really hard to screw up a job with bad coloring. You could do it, but mostly, if the artwork was decent, it came out okay. In the computer era, where you've got millions of colors and all kinds of saturations and hues and values, you can really do some damage if you don't have a good colorist working on it. I've been fortunate -- I've been able to work with some people who have all done very well by my work, but so much more of my work is visible now as well. It just cracks me up when I read these hyperbolic discussions about how terrible the new coloring is. I mean, maybe, but now I can see the guy's work that I never saw before. It's just a new balance that needs to be achieved between the black and white art and the color.

That's what I like about the Artists Editions. As much as possible without seeing the original page, you can see the linework -- and the corrections and coffee stains and rubber cement and all that stuff. To see Kirby and some of those other guys in its original form is just breathtaking. I'm thrilled such editions are being published and I'm delighted that I saved my artwork for all these years. Like so much of my career, I didn't do it with a plan. I wasn't thinking forty years ago that they'll be able print from my black and white artwork someday. That wasn't a consideration, but it turned out to be true, and I'm pretty happy about that.

Even today, do you pull out your artwork to look over your past work?

I don't as much now. That was something I did more in my early days, when I didn't have as much work lined up behind me. Now, I dig out some stuff occasionally, but of course printing is so much better. It's printed smaller, of course, so that mistakes get shrunk -- which was the idea -- but you can see the work much better now than you could in the old newsprint days. Nowadays, I tend to dig out the issues rather than try to sort through the pile of artwork.

But I've got into the habit, like an old dragon of hoarding my art. I put it in a giant pile in my studio and I lie on it and I chuckle and I do the Uncle Scrooge thing where I dive in like a porpoise. I tell fans that's what I do, and they look at me and go, "Really?" [Laughs]