For four years, before I started writing about comics, I was a reporter for a local newspaper.

I didn't have much journalistic training, and at first, every time I filed a story, I would get an exasperated call from my editor demanding, “What is this story supposed to be about?”

After a few months, I learned a simple lesson: Orient your readers to the story right away. It’s a lesson that webcomics creators should take to heart as well.

I call this the Zuda Test, because I formulated it while reviewing the comics at Zuda.com, DC’s webcomics competition site. Each month, I and my Digital Strips colleagues Steve Shinney and Jason Sigler read all ten of the comics at Zuda and discuss the pros and cons of each one.

Month after month, I found myself making the same complaint: After eight pages, I had no idea what was going on.

Eight pages should be enough space to establish the setting, introduce one or more characters that are worth caring about, give some sense of what the comic is about, and get the story rolling. This is obviously most critical for longer stories, but gag-a-day creators would do well to establish their premise and characters clearly as well.

A surprising number of stories flunked this test. Many jumped right into the action, often starting off with a complicated fight (Zuda creators love a good fight) between utterly unknown characters, leaving me unsure who to root for.

Each Zuda page includes a space for a text-only synopsis, and that is where I would often find finely crafted, intricately thought out backstories and alternate universes.

Unfortunately, that’s not where they belong. They belong in the comic.

It’s easy to see how this can happen, especially when a writer has been thinking about a story for a while and is already mentally living in that world. Things that seem natural or self-evident to the writer may simply puzzle the reader, and the wise writer will anticipate that and answer questions before they become distracting. (Having an outsider read the comic with fresh eyes is an excellent way to anticipate this.)

It’s not necessary to clutter the story with text boxes or clumsy expository dialogue. (“Bill, don’t forget that you’re my brother!” “That’s right, Sue! And Dad sent us here to the Planet Zorgov to retrieve our family’s uranium stash before it disappears in the coming apocalyptic explosion.”) It’s OK to introduce a complicated premise a little at a time or to start the reader out in the center of the action and then pull back a bit. But after eight pages the reader should have a sense of where the story is going and who the good guys and the bad guys are.

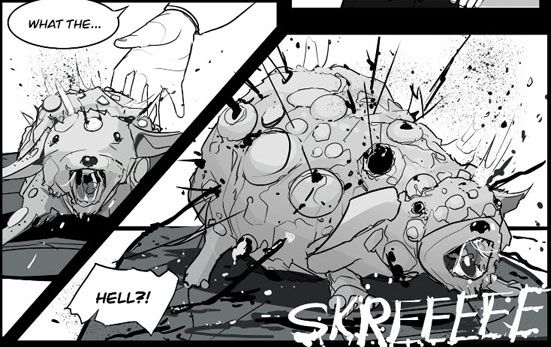

Interestingly, this clarity doesn’t necessarily correlate with success on Zuda. Take last August’s competition, for instance. I thought Matt and Gabe White’s Gulch failed the Zuda test miserably. A woman walks into a boutique and hands the manager her dog. The dog explodes, and chaos results. The problem is, I had no clue as to who she was or why this was happening. I couldn’t even figure out whether she expected the dog to explode or not. The synopsis revealed a detailed story that was not at all evident in the comic. But something about this one—the action, the promise of a plot, the hot babe—made the readers vote it number one, allowing the creators to expand their story. Now that it’s up to 37 pages, the plot is a lot clearer and I'm enjoying it more.

The comic that I would have picked that month, though, was Shock Effect, by John Lang and Ian Daffern. That comic also started off with plenty of action, the but the creators took the time to put it into context. I knew right away that the girl I was looking at was a sympathetic character. I knew that society was breaking down in the face of an alien invasion. More details could be supplied later, but I had the tools I needed to follow the story.

Looking at a lot of eight-page comics helped crystallize this principle in my mind, but it applies elsewhere as well. Here's a non-Zuda example that I’m enjoying right now: the romantic comedy Dovecote Crest. In just seven pages, the creators give us the setting, introduce the main character and get us to like her a bit, and hint at what is to come. They do it cleverly, too. By page eight, I knew I wanted to keep reading.

A comic with a slow build can turn out to be pretty good in the end, but the Zuda test is a good constraint for a creator to keep in mind. Eight screens is about as much as any reader will devote to a story that makes him or her feel disoriented. As my editor used to say, “It doesn’t matter if you write the greatest story in the world. If they don’t know what it’s about, no one is going to read it.”