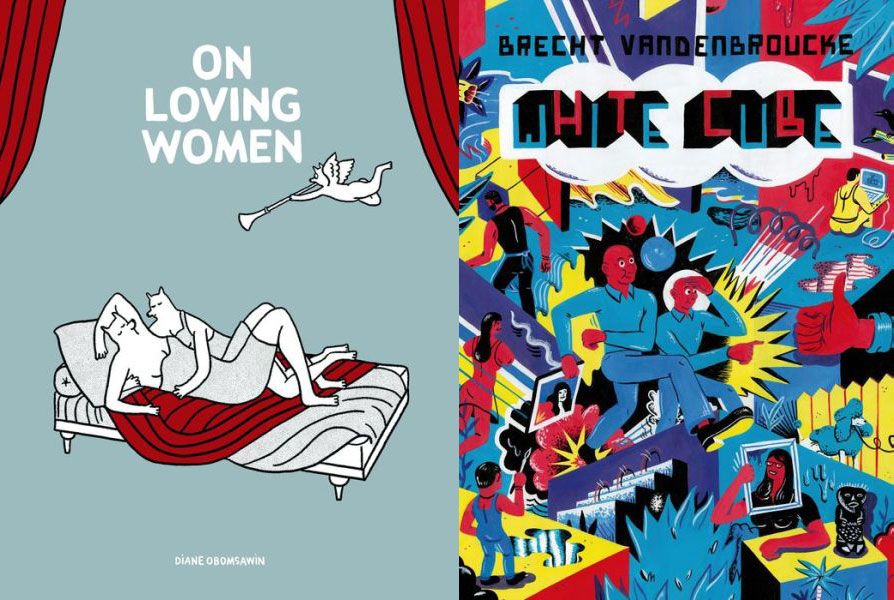

Diane Obomsawin's On Loving Women and Brecht Vandenbroucke's White Cube have two things in common: First, they're both published by Drawn and Quarterly; second, they're both collections of very short, individual comics stories riffing on a single theme that defines them as books -- little pieces contributing to a great, big whole.

Wait, did I say they have two things in common? I meant three -- they have three things in common: Both are excellent.

Beyond those commonalities, there's not a whole lot of overlap between the two works. On Loving Women is a series of six- to nine-page, black-and-white short stories about the real-life sexual awakenings of various women who love other women. White Cube is a bunch of one- or two-page, fully painted, full-color, silent strips about modern art and related subject matter. The former is pretty funny, but mostly by virtue of the way Obomsawin tells a joke, as the stories are more conversational anecdotes than gags. The latter is very funny because it's a collection of comic comic strips (although some of those jokes are pretty dark).

Each strip in On Loving Women has a similar title, assigning it to its source: "Sasha's Story," "Marie's Story," "Diane's Story." Who are these women? Friends and girlfriends of Obomsawin, the Canadian animator, filmmaker and comics creator probably best known among English-speaking North Americans for her 2009 Kaspar.

Each deals with the dawning of the women's sexual identity, and thus includes moments where they realize they like other women instead of men, when they come out, when they have their first dates and/or sexual experiences and when they try and fail to have first dates and/or sexual experiences.

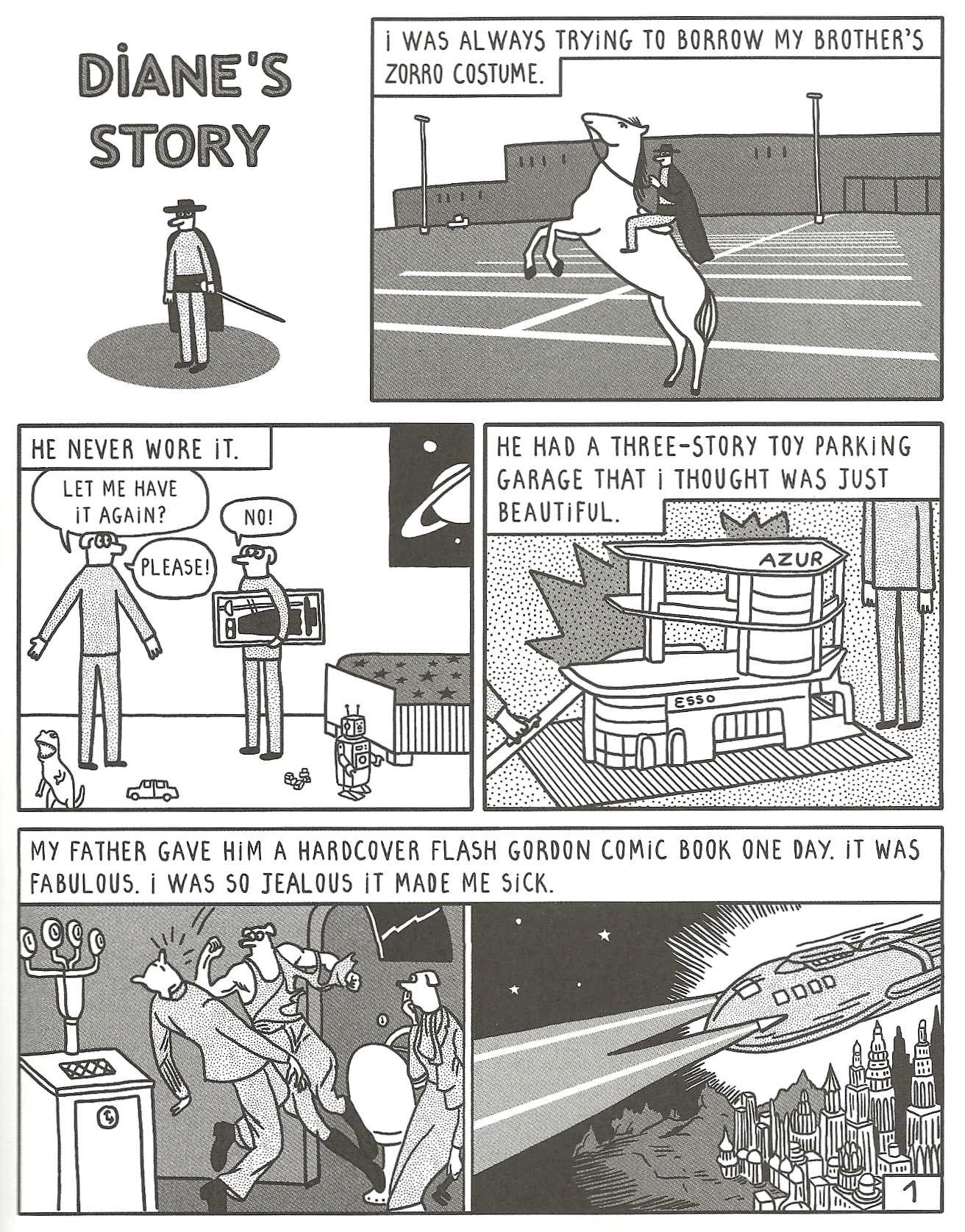

Obomsawin divides her pages into pretty standard comics grids, and her imagery is super-simple, of the deceptively simple, almost child-like sense style design. Though there's a lot of sex in the book, it's not exactly sexy. The women are curve-less and, in fact, not drawn as women — they have the heads of mice, rabbits, deer and birds. Notably, whichever animal Obomosawin chooses to anthropomorphize in a particular story, she's consistent throughout; just about everyone in the bird story is a bird, for example (one notable exception is the first story, in which Mathilde, a canine of some sort, begins by talking about how much she loved horses as a little girl, and then noting that the women she loved always have horse faces, and Obomsawin draws these women with the actually heads of horses).

On the occasions when they shed their clothes, their nipples, like their belly buttons, are just little dots.

Her art can be more detailed, of course, as she demonstrates by rather perfectly covering H.G. Peter's version of Wonder Woman (Mathilde found Wonder Woman somewhat horse-like, and her first girlfriend was "half horse, half Wonder Woman") or Alex Raymond's Flash Gordon (as a little girl Diane is jealous of the hardcover Flash Gordon comic her father gave her brother; she got a set of silver spoons).

The women's stories appear as narration in narration boxes above the panels, and she dramatizes them with images below, occasionally resorting to cartoon imagery ("I was electrified," a woman might say, while Obomsawin draws the woman's avatar as a skeleton, being struck by a bolt of lightning), but more often than not simply using super-sharp timing to break beats out of the story, and add some commentary from a character (in Marie's story, for example, she says that once her mother found out she was a lesbian, she took her to a gynecologist; "Honestly, Ma'am!" the doctor scolds her mother).

While the content is sexual enough — abstracted though the drawings may be — to make it an adults-only comic, if there's really anything all that subversive about the book, it's in how non-subversive the book is. Story after story is full of weird, funny, silly, embarrassing details about awkward women stumbling clumsily into coming to grips with their sexuality and learning how relations and relationships work. And though the specific details will vary from person to person and story to story, that's universal, whether you're a woman who loves women or men, or a man who loves men or women.

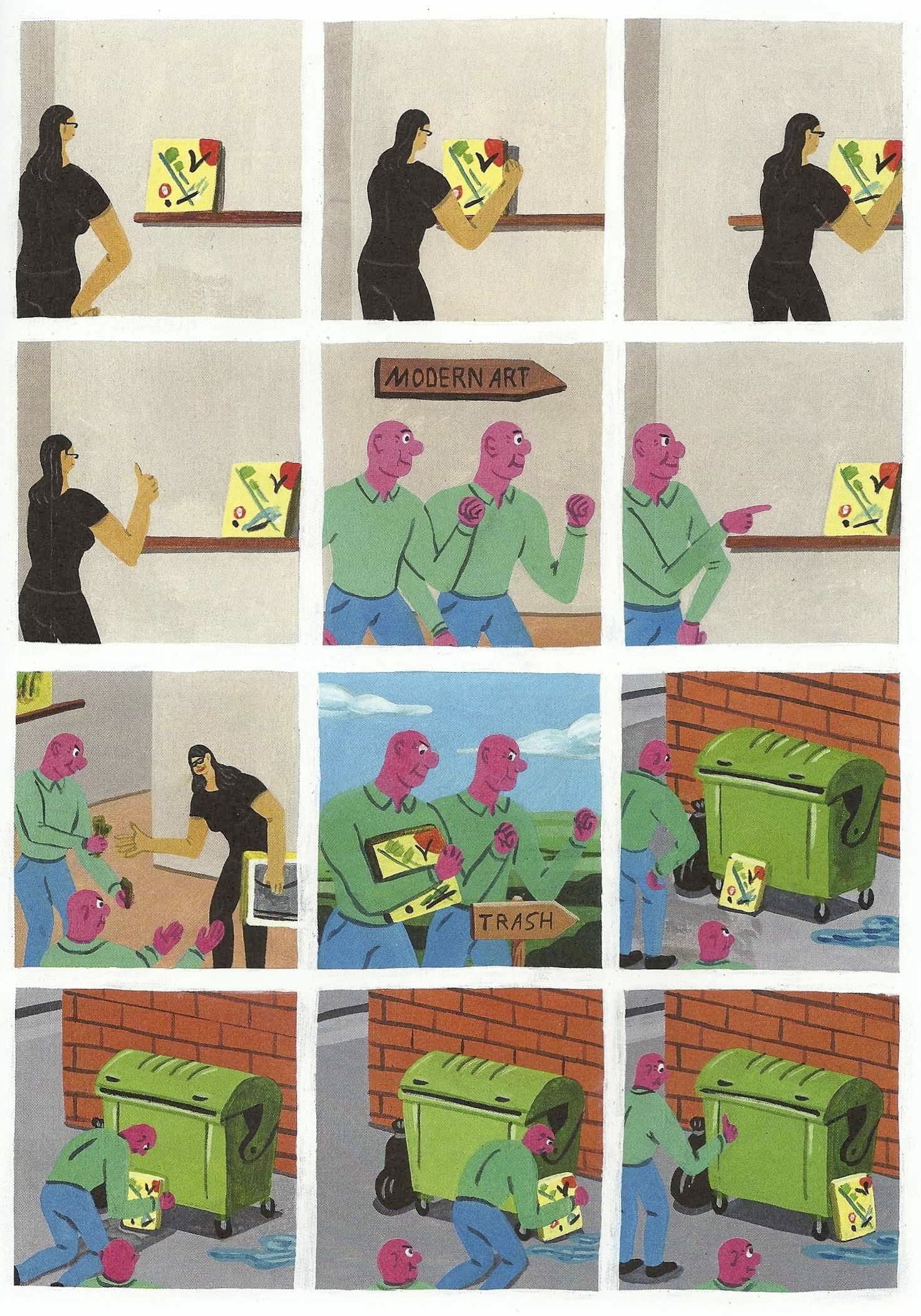

White Cube's subject matter, art, isn't quite so universal as sex and romance, but just because there are jokes that reference Gordon Matta-Clark , Damien Hirst and Marina Abramovic (who I had to Google in order to get the last panel of the strip featuring her) doesn't mean the comic is necessarily high-brow: There's also a one-page strip built around pooping and punching.

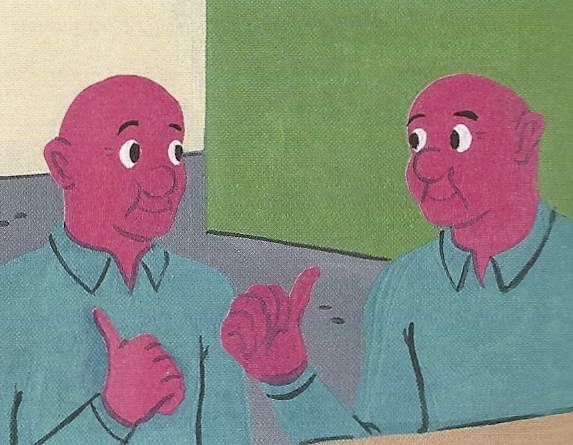

The stars of the strip are two identical bald, pink-skinned men in matching blue pullovers and blue pants (who reminded me of Life in Hell's Jeff and Akbar in their identicalness). They never speak — none of the characters does — but express their approval or disapproval via thumbs up or thumbs down. When they are truly moved, they may shed a single tear. Otherwise, Vandenbroucke relies on the shapes of their eyes, eyebrows and mouths to express their often complex emotions.

In the first strip, the pair are shown running down the street until they arrive at a modern-looking building, marked "White Cube." Inside, they follow signs labeled "modern art." From there, the rest of the strips are short gag strips, occasionally breaking for a piece of Vandenbroucke-produced not-comics artwork featuring the characters.

Vandenbroucke goes for a broad definition of art here. There are gags about classic pieces an the way people react and interact with them (Art 101 stuff like The Birth of Venus, Guernica, Andy Warhol, Roy Lichentenstein, The Venus De Milo, Michelangelo's David — always good for dick jokes), and riffs on the art produced by little kids, as well as fashion, tattoos, vacation photography, graffiti, home decor and so on.

That said, the jokes are mostly executed through playful visuals, and one need not know much about most of the things being discussed to appreciate the way Vandenbroucke manipulates they physics of a cartoon world for humorous effect, or to laugh at a swear word, slapstick or scatalogy. Featuring low-brow jokes about high-brow subjects, and high-brow jokes about low-brow subjects, White Cube achieves a sort of zen no-brow.

Words probably aren't apt to describe the overall quality of this wordless comic, so perhaps I should sum up my feelings for White Cube the way its protagonists might do so: