"Last Sons of America" #2 from BOOM! Studios was released on the final Wednesday of 2015. It's a book I'd be checking out regardless, because my friend Matthew Dow Smith is drawing it (and doing a lovely job). But I'm also interested in "Last Sons" because it's the first title written by Phillip Kennedy Johnson. I met Phillip a few years ago, when I helped him get an article published here on CBR that drew parallels between two American art forms, jazz and comics. The subject matter was a natural for Phillip, whose "other" job is playing trumpet in the U.S. Army Field Band.

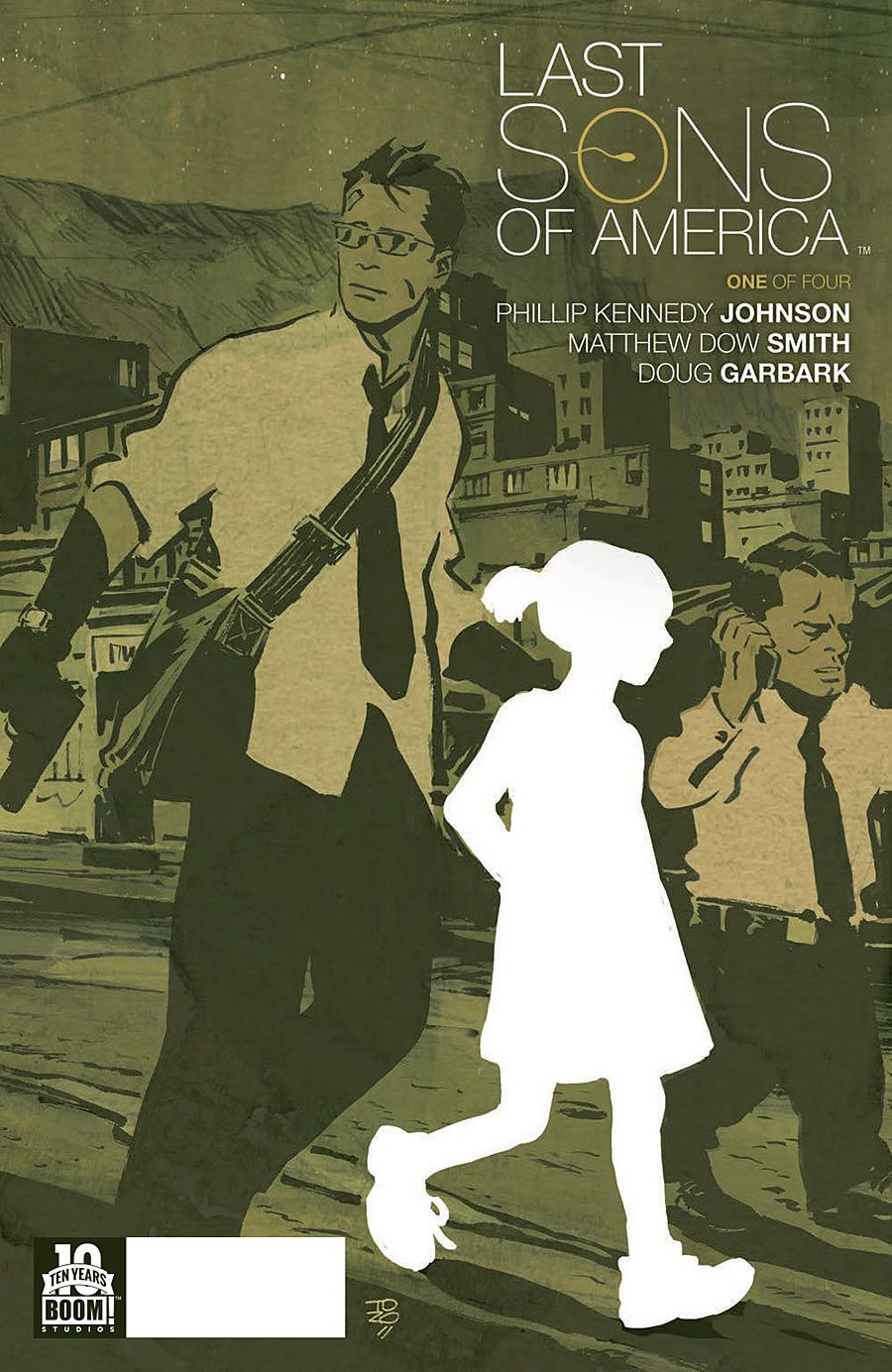

PREVIEW: Last Sons of America #1

In the time since, I've given Phillip some writing advice as he pursued a comics career. Now his first project, "Last Sons of America" is seeing the light of day, and garnering positive buzz. We talked about his comics background, the process of breaking in, and what it was like to have his first project hit shops.

Ron Marz: Background first. Tell me about comics, tell me about music.

Phillip Kennedy Johnson: I don't remember a time before I read comics. One thing there was a lot of in my house was stuff to read, much more so than toys. Dad would sometimes hit up garage sales and flea markets and buy cheap boxes full of old comics for me. There was a lot of DC, mostly Superman and Batman; a lot of Disney, some Spider-Man Team-Ups. I probably learned the basics of reading from my parents reading to me, but I learned to really read from those comics. And I loved the heroics of the superhero books.

I did a lot of drawing as a kid, and wanted to be a comic artist for a long time. In high school I started focusing more on music, and practically gave up art when I decided to pursue music as a career. I went to school for music, played with the Glenn Miller Orchestra for a while, and now I play trumpet with the U.S. Army Field Band, Washington, D.C. It's one of the Army's "premier bands," tasked with touring the continental United States and playing concerts for the American people. We tell people about the work their Army is doing, honor our veterans, and help them to get to know their Army better. I've been in the band about 10 years.

So now your first two issues are on the stands. What was that like, walking into the comic store and seeing something you had created on the shelf?

I'm extremely proud of that book, and the work we all did on it. Seeing it in print felt great, but it wasn't so much that it was finally on the shelf. I wish I could say I had this surreal, out-of-body experience seeing the physical books, but honestly, getting a book done was so many years in the making, I was ready for it. It was really rewarding seeing it for the first time, but I still get that feeling seeing it on my desk weeks later. It's a good story, I'm proud to have made it with everyone involved, and I'm excited to finally have the chance to share it with people.

Let's go back to when I first met you. Unless I'm mistaken, I think you reached out to me via email first, and showed me the essay you had written comparing comics to jazz, which ended up being printed here on CBR. And then we met in person out at Comic-Con International in San Diego, right? You were obviously taking this pretty seriously, to go to the expense and effort of San Diego.

Yeah, that's exactly how it happened. As many comics as I had read as a kid, I didn't know as many creators' names as I should have. I owned your "Green Lantern: Emerald Twilight" arc and loved it, but I didn't know who you were or everything you had done in comics when I emailed you about the jazz article. I just liked your Shelf Life column, thought the writing was like-minded enough to what I had written, and wanted your opinion on what I should do with it. When I realized who you were, it was a big head-on-desk moment.

By the time I got to San Diego, I was writing comics and taking it seriously. I had written a six-issue series I was proud of, was working on another one, and had been to a few conventions on the east coast. San Diego was something I wanted to see, partly as a bucket list thing, but mostly because so many people I wanted to meet were there, including you. Thanking you in person for your help with the article was a priority.

I broke my rule about reading other people's scripts, because I read one of your early stories, the one with art by Scott Hampton. Talk a bit about that. Was that your first attempt at a comic?

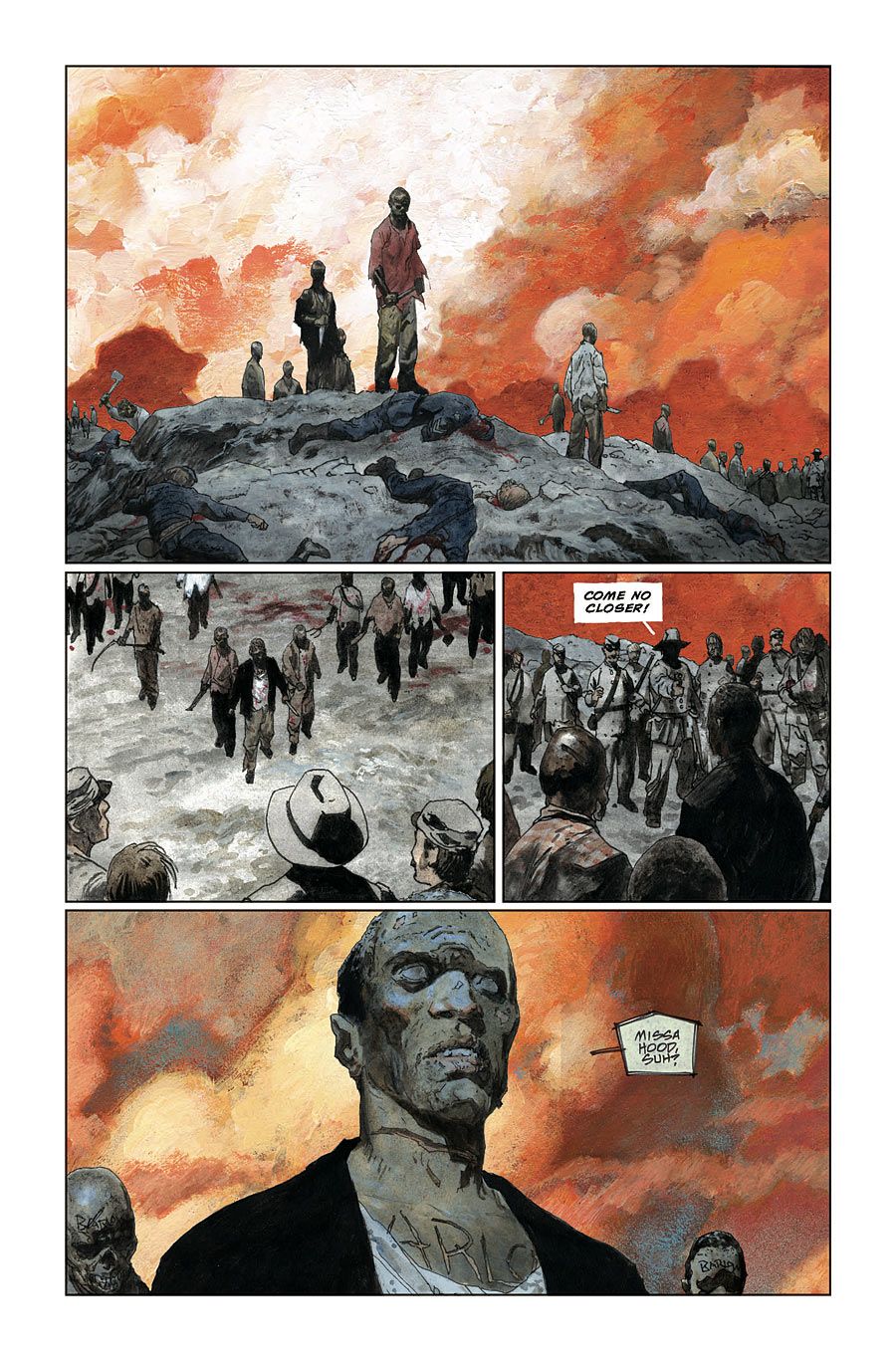

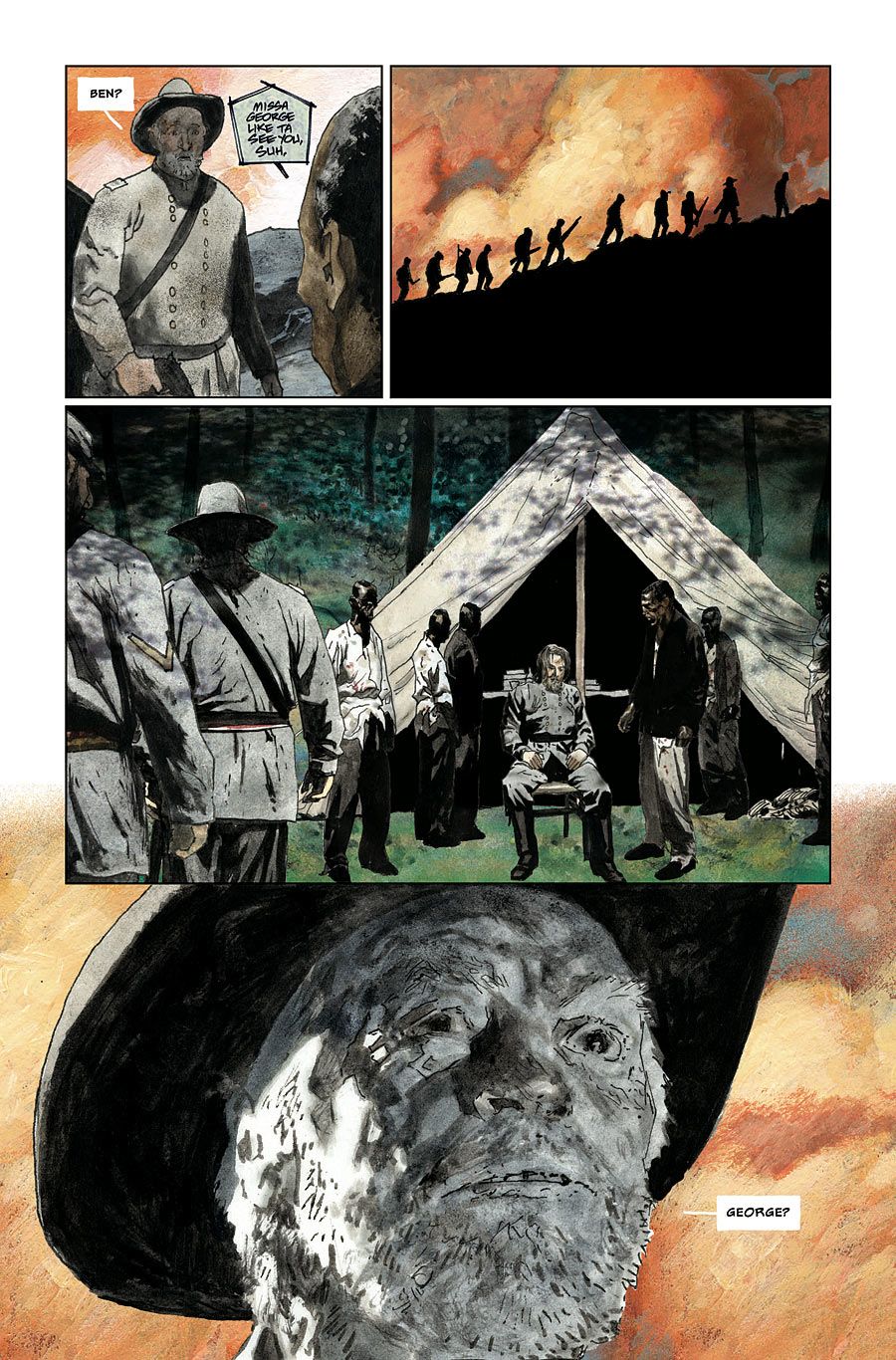

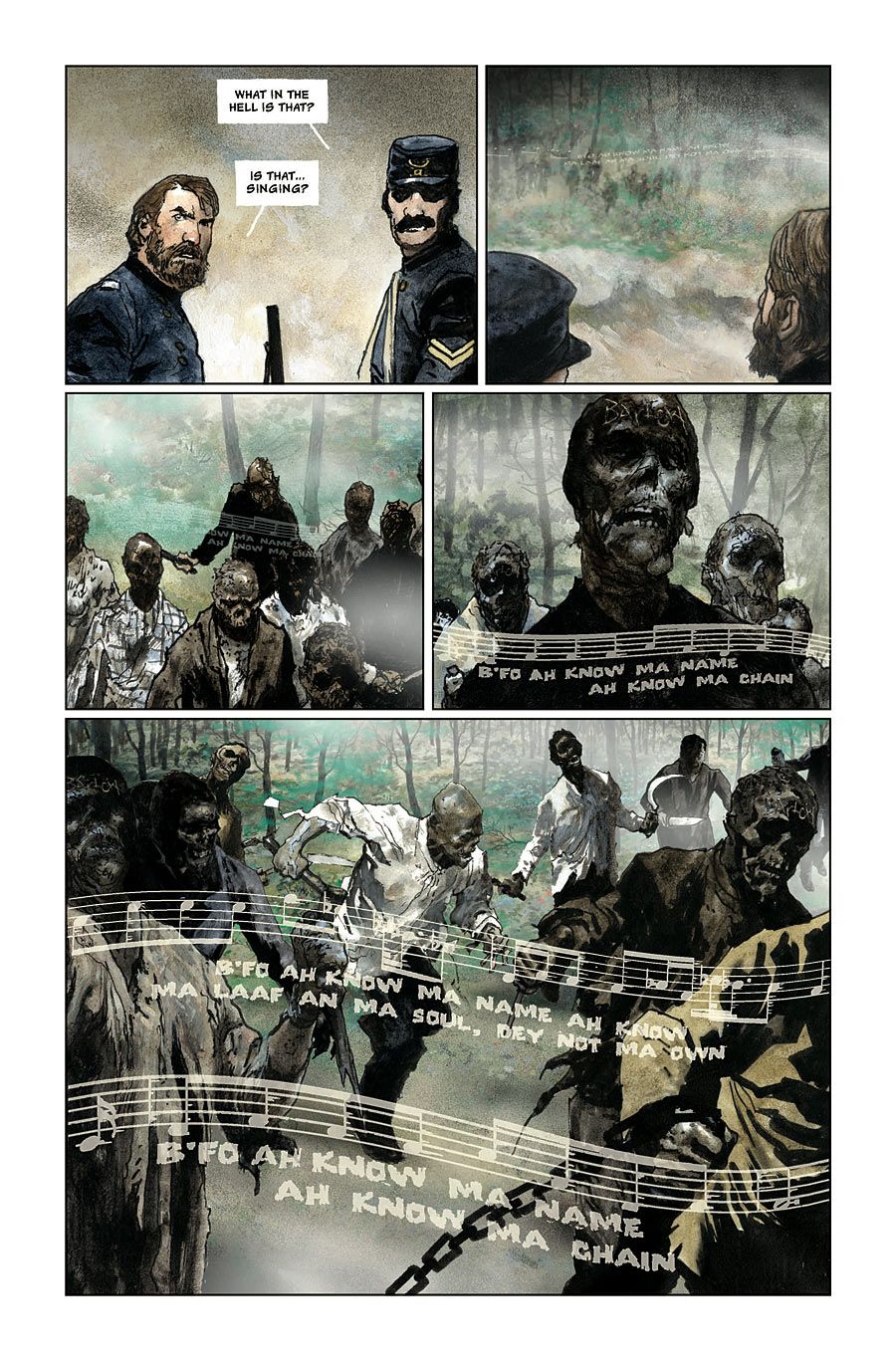

That one was called "The Lazarus Slaves, or The Damnation of George Washington Barlow." It was the first one I invested money in, but not my first comic, no. My first script was a gift to my sister Carrie, during the summer she graduated high school and turned 18. I wrote a story called "Vessel" that featured her as the hero, and our brother Bill, who's a professional illustrator now, drew a scene from it. Even before that, I think the three of us had worked on a little comic together when they were in middle school, as a way to encourage their interest in art. But "Vessel" was technically my first comic script, once I had educated myself a bit on how it was done. After that, I wrote another one for Bill called "The Well," a poem that worked out to 12 pages of black-and-white art. But "The Lazarus Slaves" with Scott Hampton was the first one I wrote for another artist, and that I invested in.

That story was a good calling card, because you had not just an outline or a script, but actual finished pages. I think having a comic, and not just text, gives someone a huge advantage when they pitch. But, of course, it also costs money. Was investing in a professional artist a tough decision?

No, it made sense. I know not everyone goes about it that way, but I believed in the story enough to invest in it, and Scott was a perfect fit to do the artwork. I love the pages he did, and I still hope to make that book.

Writing comics is a fairly specialized skill. Breaking down a script so that you're telling a visual story is not something everyone can do. A lot of my artist friends regularly complain about being handed scripts that can't be drawn as written, because the writers simply don't grasp the process. How did you go about educating yourself in the script process?

I don't claim to have ever been a great artist, but I imagine having some art background helps to "see" the script as a series of images. As far as educating myself on the nuts and bolts of a comic script, it started with that script I wrote for my sister's birthday. I was well out of the comics scene by then, hadn't opened a comic in years. When I decided we were going to make this thing, I walked into a comic store and picked up where I left off. I had no idea what the state of the art was anymore. I think the last books I had read month-to-month were the "Batman: Knightfall/KnightsEnd" books, your "Emerald Twilight" arc, some post-"Return" mullet Superman, and "X-Men: Age of Apocalypse." Twelve years go by, I walk into Third Eye Comics, and the owner shows me "The Boys," Whedon and Cassaday's "Astonishing X-Men," "Locke & Key" -- it was pretty amazing how far everything had come while I'd been away. And even back when I was reading more regularly, I had never been in a real comic shop before.

I also bought several how-to books that made it a lot easier. One was called "Panel One," and had several scripts by prominent writers. The McCloud [book "Understanding Comics"] is great, of course. The first how-to book I bought, and still the most helpful, was Andy Schmidt's "The Insider's Guide to Creating Comics and Graphic Novels." That had contributions by a ton of great people, and gave a terrific overview of the process of making comics. It was invaluable when my brother and I were getting started.

I feel like you got both ends of the "breaking in" memo. Obviously the work has to be good, but you also have to be a presence at conventions, and in particular, in the bars and gathering places after conventions. I feel like the social aspect of comics is hugely important. Do you feel like being part of that helped you?

Definitely. People talk about the comics "industry" and the comics "community," but that's really a difference of context or perspective. It's practically the same group of people. If you want to be a part of the industry, you have to put yourself in the community, both online and at conventions. Getting to know other writers, artists, editors, publishers, marketing pros, retailers, and especially other fans is a crucial part of the process for me.

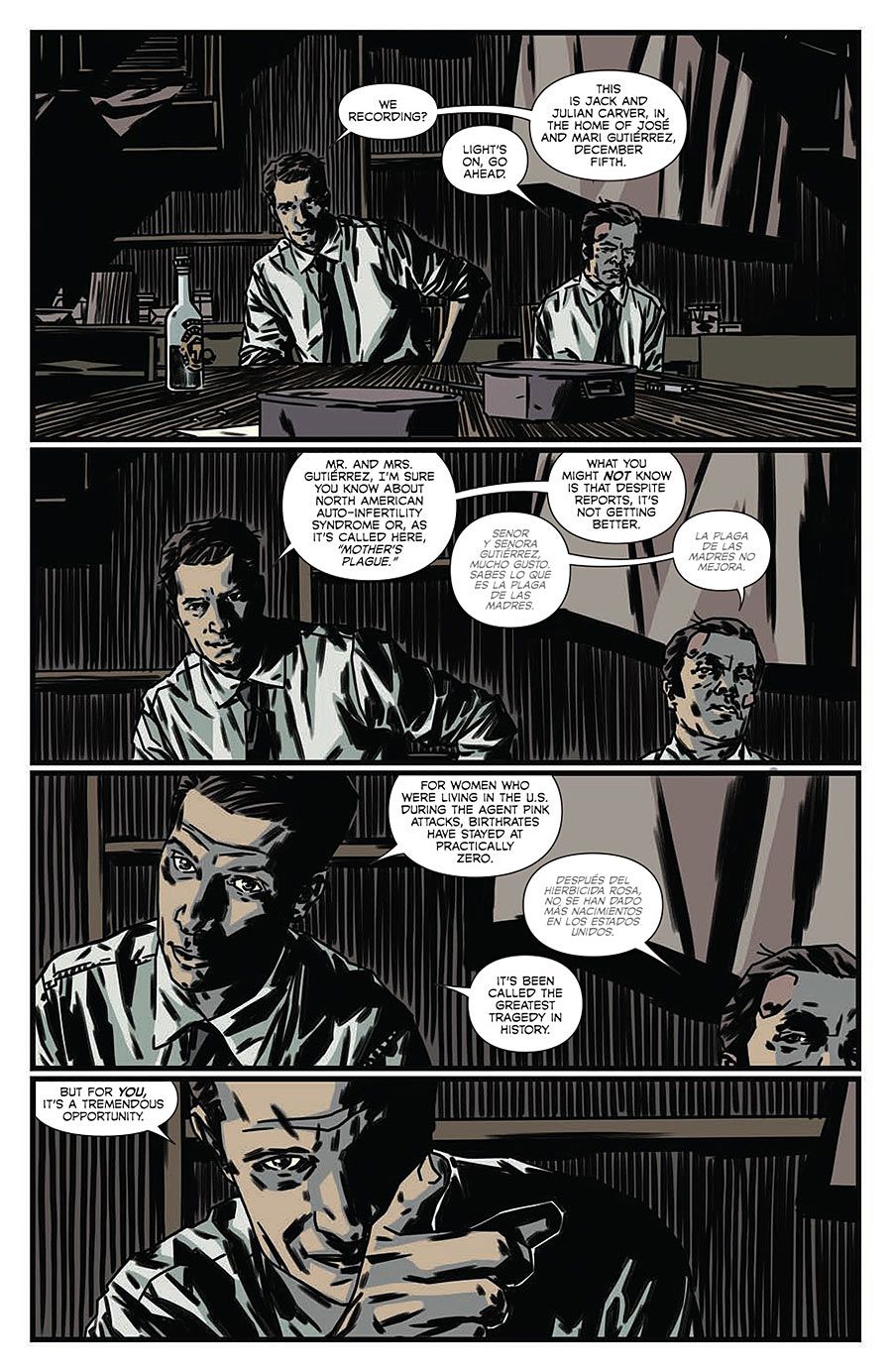

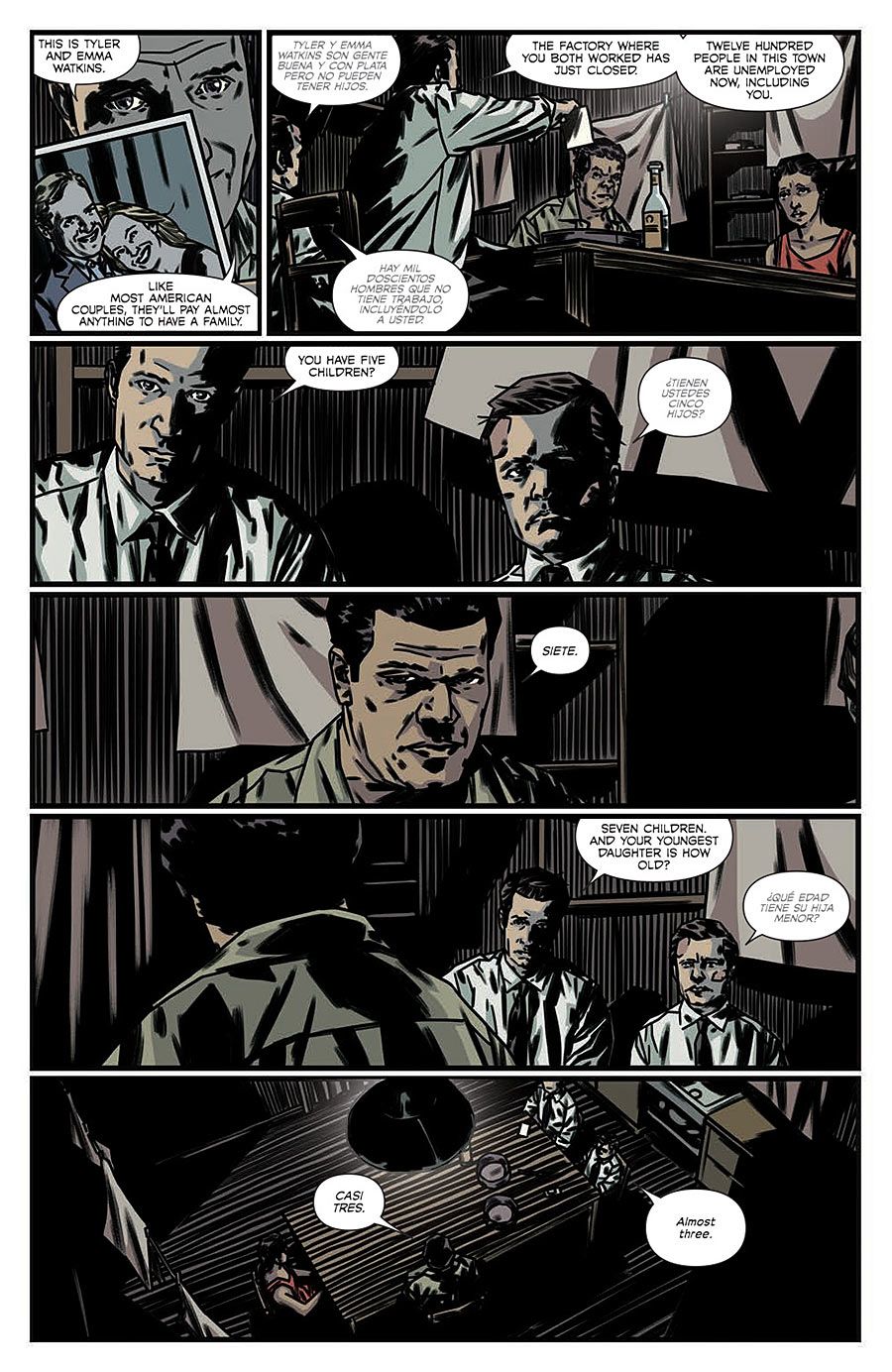

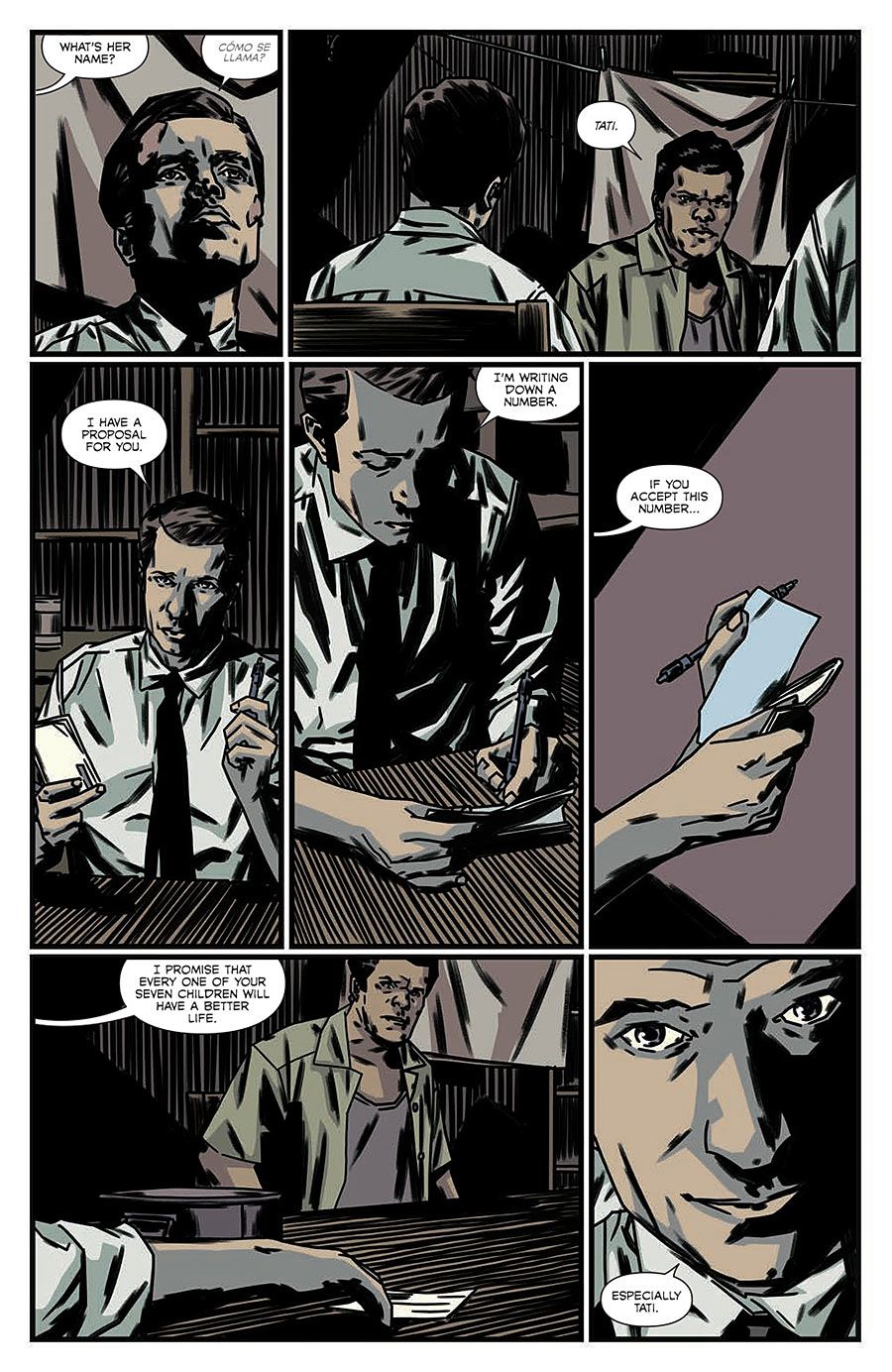

Let's get to "Last Sons of America" from BOOM! Studios. Was this project the same situation where you had an artist, my buddy Matthew Dow Smith, attached and drawing pages before the book was placed with any publisher?

Yes. I met Matthew through you at Baltimore Comic Con a few years ago, and we became friends. I loved his work, and I pitched him an idea for a book that ended up becoming "Last Sons." A few months later, I had a Kindle loaded with four different pitch packets for four wildly different books, each with finished artwork by a different artist. One of those was "Last Sons of America," and it became the first one to get printed. The "Last Sons" pitch had two covers, six pages of colored and lettered interiors, two character designs, and a one-page synopsis.

I know you have other concepts, other stories. Was "Last Sons" a project you specifically picked to be first, because it was the way you wanted to introduce yourself to the market? Or did "Last Sons" end up being the first one just through happenstance?

I was showing my other pitches with equal enthusiasm, and as a guy trying to break in, if one of my other books had been picked up first, I would certainly have gone with it. But in retrospect, it was good for "Last Sons of America" to be my first printed work. At this point, my primary concern is avoiding pigeonholes, being labeled as a specific kind of writer. That's something I think you have managed to navigate extremely well. Neil Gaiman's another great example. All his work feels like him, but he tells stories across many mediums for nearly all audiences, which I admire a lot.

Thanks for saying. I've always tried to do different things, more for the sake of keeping myself interested and fresh. Now, I always tell people one of the biggest jumps in the learning curve is seeing your first book finished. You see everything put together: the storytelling of the artwork, how the lettering marries up to the artwork. Did you find that to be true?

Yeah, I would agree. On your early books, when you see your writing come back with artwork, things don't always look the way you expected, especially if you're still getting to know your artist(s). When I first got Scott's "Lazarus Slaves" pages back, every word of the dialogue had been lovingly chosen and I was sure it was right, but after seeing it on the finished page, I changed a ton of stuff. That still happens sometimes, but that first time was pretty humbling. It completely changed how I approach layout and especially dialogue.

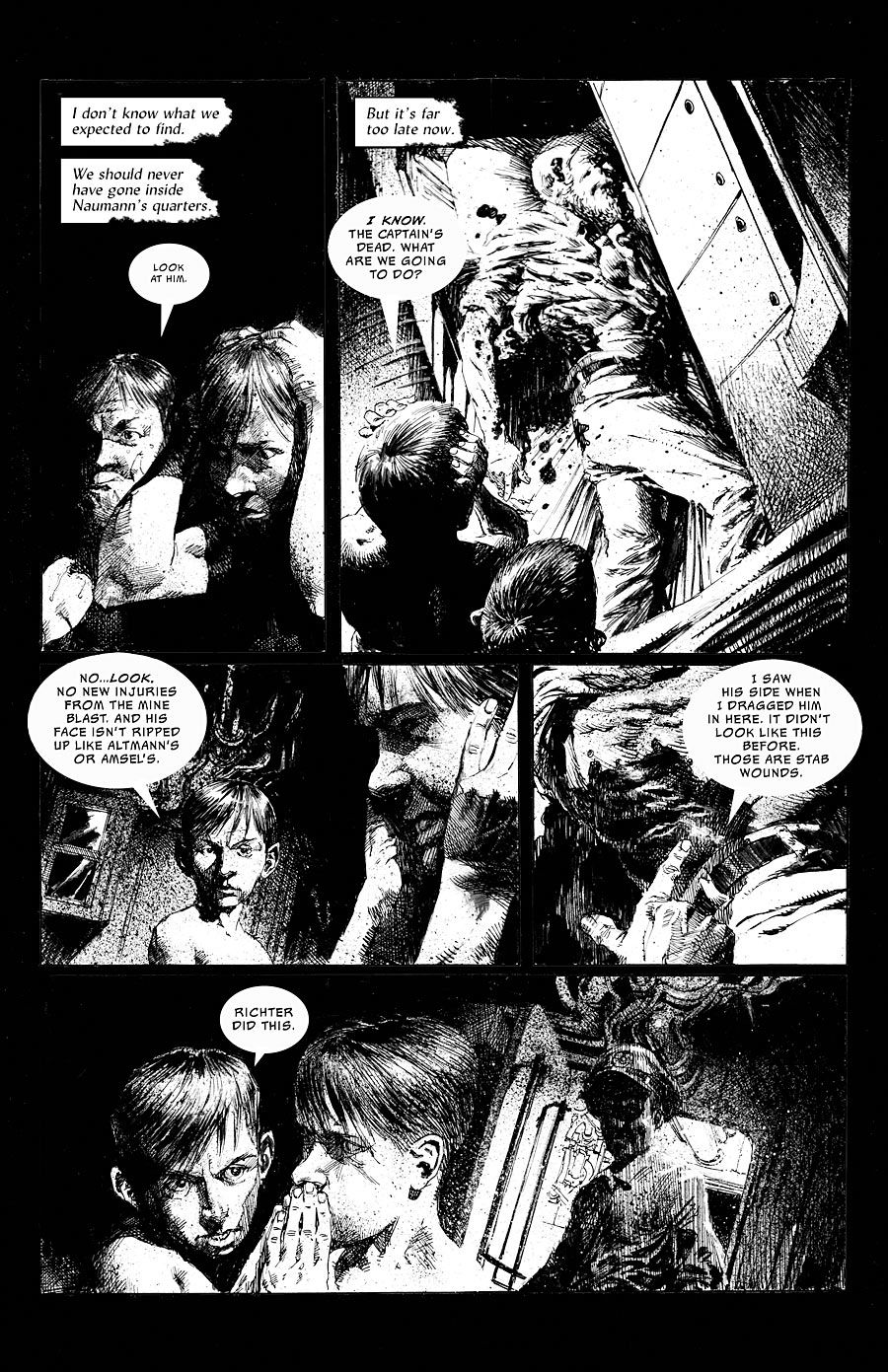

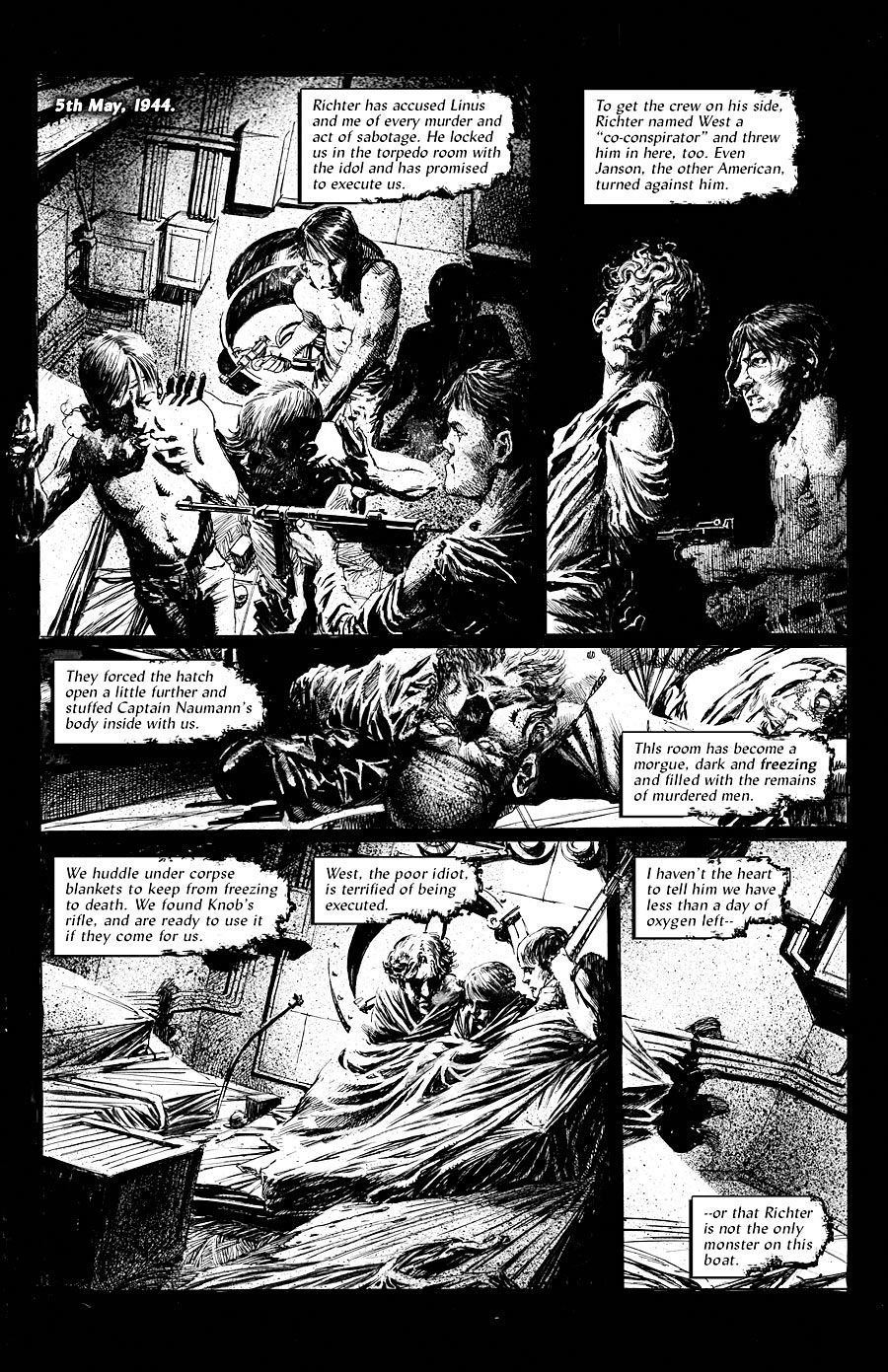

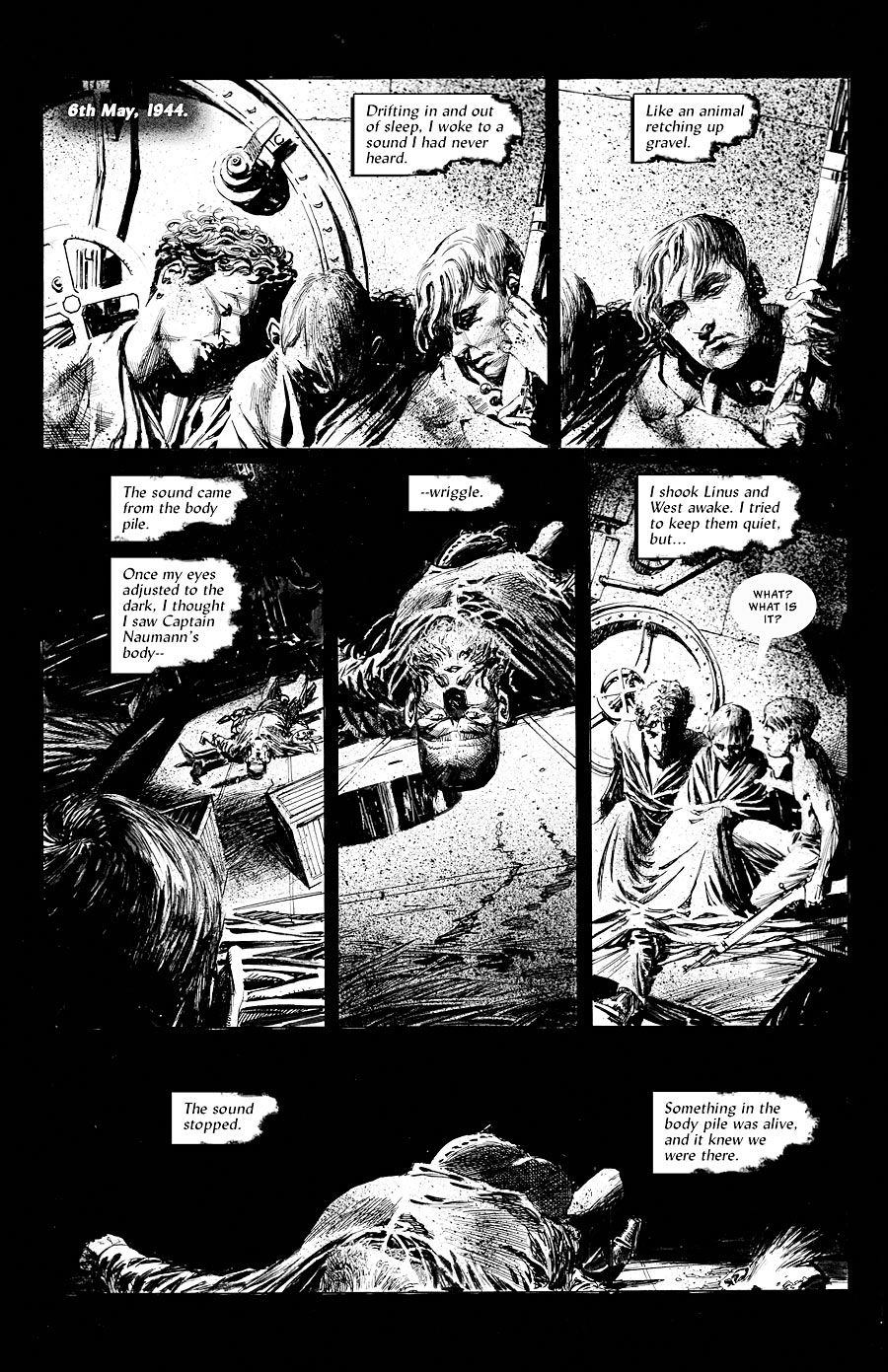

You have your webcomic, "The Lost Boys of U-Boat Bremen" updating weekly. Do you find that to be a different experience than creating a print comic?

Completely different. The weekly schedule is tricky, mostly because I still want to put it out in 22-page printed issues when it's finished. Every single page has to have a mini-ending or a cliffhanger, and also a clear purpose, something that pushes the story forward to next week. But we can't let it get too segmented or choppy, or it won't work as a monthly book. I still want longer scenes that compel the reader forward, and a huge "holy crap" moment every 22 pages to build towards. As far as pacing, "Last Sons" is a much easier book to write. You still want moments in the bottom right panel that make you turn the page, but you don't have to constantly balance the compelling page ending with overall flow. Not as much, at least.

There are other big differences, too: the tone of the books, the dialogue styles, working with or without editors. Doing both books at once has been a great education.

Comics is a part-time gig for you. How do you balance your work with the Army band, especially the travel, not to mention being a relatively new father.

Time management has been the most challenging part of it. I don't see comics as a part-time job, I see it as having two careers, one in music and one in writing. To get everything in, I have to constantly multi-task. Whenever I'm in line at the pharmacy, eating by myself, on the subway, or in the passenger seat of a car, I'm writing. When I work out for my Army obligations, I listen to comics podcasts, or music my band is performing. When I'm spending time with my son, sometimes I'll get in a little practice time by playing songs for him on my trumpet, or teaching him how to play. I either have my computer or a kindle with me pretty much always. It's a busy time, and I can't afford to waste a minute.

I know you have more stories you want to tell. What's next?

I'm finishing up a crime one-shot with a Washington, D.C.-based musician and artist named Scott Van Domelen, an old friend from my days with the Glenn Miller band. This is his first comic, which I'm excited to be a part of. It's called "Killing Marcus," and is inspired in part by David Lapham's "Stray Bullets" series. Depending on how we decide to distribute it, we might make it the first of a series of interconnected one-shots. My colleague Dustin Mollick and I will also be returning to the "BAND!" series on Musicomic.com soon, which I'm looking forward to.

Beyond those two and finishing "The Lost Boys of the U-Boat Bremen," some other books are starting to take shape that I cannot wait to talk about. It's too early to give details, but the thought of telling those stories already has me super stoked. I love this job.

Ron Marz has been writing comics for two decades, and thinks it's pretty much the best job ever. His current work includes "John Carter: Warlord of Mars" for Dynamite, "Skylanders" for IDW, "The Protectors" for Athlitacomics on Madefire, and Sunday-style strips "The Mucker" and "Korak" for Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. Follow him on Twitter (@ronmarz) and his website,www.ronmarz.com.