Tim Callahan (whose blog can be found here) just came out with a book about Grant Morrison. Here, then, is a guest piece by Tim. - BC

To promote the release of my new book, Grant Morrison: The Early Years, I am doing a bit of guest-blogging here at CSBG.

My book, in case you haven't heard, explores Morrison's early work from Zenith to Animal Man to Doom Patrol, and includes detailed analyses of those works as well as the much-maligned slice of genius known as Arkham Asylum and the generally overlooked "Gothic" storyline from Legends of the Dark Knight. But I didn't want to write about any of that stuff here. I wanted to do something a bit different.

So I decided to look at an even earlier Morrison work: his very first story for 2000AD. Written over a year before he launched Zenith, Morrison's first entry into the "Future Shocks"i series suggests the direction his career would take. In this early story, and the ones that follow, we see indications of the major themes and motifs which would dominate his work throughout the decades. These "Future Shocks" weren't his very first comic book stories,ii but they were the beginning of the first major phase of his career, and his initial attempt, in particular, is worth looking at in detail.

(Click on any image to enlarge)

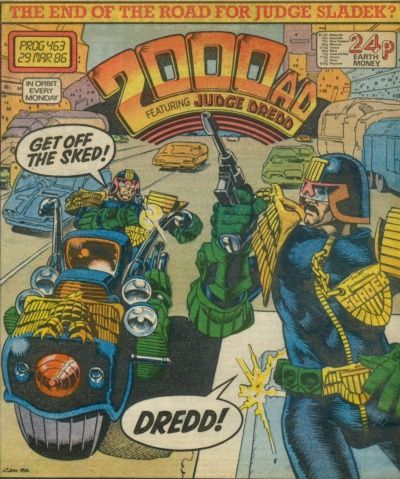

His first "Future Shocks" story appeared in 2000AD prog 463, cover dated March 29, 1986. The two-page story, "Hotel Harry Felix!" immediately establishes Grant Morrison as a writer concerned with the relationship between the mind and the body. As I argue in my book, many of Morrison's early works obsess over the mind/body connection. In Zenith, the "villains" of Phase Four achieve a state of pure consciousness, yet their attempt at transcendence is blocked by a physical prison. In Doom Patrol, Morrison gives us a hilariously literal battle between the mind and the body in the issue where Monsieur Mallah and the Brain invade Doom Patrol headquarters. (That story, from Doom Patrol #34, features one of my all-time favorite lines, as the Brain lands on the table next to Cliff Steele's currently disembodied brain and says, "At last we are face-to-face in open combat!"iii) In Arkham Asylum, Morrison gives us a story in which the physical boundaries of Arkham Asylum symbolize the fragmentation of Batman's mind. In that graphic novel, the mind is healed through the actions of the body within the mind (huh? But, yeah, that's what Arkham is all about.)

In Morrison's "Hotel Harry Felix!," drawn by Geoff Senior, we meet the down-and-out Harry Felix, once a wealthy composer, now a self-proclaimed "tramp." As Felix narrates, he was "looking forward to making [his] second million in creds... / And then the aliens arrived." But, since this is a Morrison story (even at this early stage in his career), it doesn't give us a conventional alien invasion. Felix says, "They didn't need spayships, not these suckers! No, sir, they just dropped outa nowhere, straight into my head." Morrison's use of the homophone spayship instead of the traditional spaceship, pokes fun at the anal-probing/sexual reproduction conventions of the alien abduction genre in a single word, and it provides the slight verbal twist that continues to make Morrison's dialogue surprising even today. And the idea that the aliens dropped "straight into [Felix's] head" fits perfectly into Morrison's mind/body obsession, a concept Morrison expands upon as the story continues:

Felix says that the alien leader, Ziggy (in tribute to glam icon David Bowie, aka Ziggy Stardust, no doubt), "told me my head was a five-star hotel and that as manager I had to do what he said!" Could this have been the germ of the idea that would become Arkham Asylum? Possibly, but it's more likely that the mind-as-house motif is simply a reflection of Morrison's philosophy, and such philosophy reveals itself through his stories. Nevertheless, the battle between the mind and the body continues in "Hotel Harry Felix!" as Felix reveals that the alien leader "could control [Felix's] body" when he forced Felix to destroy his musical instruments to keep the "hotel" quiet.

It's quite conventional to assert that the mind controls the body, but Morrison provides a twist to the story by demonstrating what Felix does to repel the alien invasion: he uses his body to battle the inhabitants of his mind. "My plan ," says Felix, "was simple: to lower the tone of the aliens' hotel...i.e. me. / So I hit the streets -- and the bottle. Within a month I was a walking slum..." His scheme works, and Ziggy tells Felix that the aliens are leaving Hotel Harry Felix because, as Ziggy says, "you can't expect us to live in this squalor." Yet Felix didn't count on the logical consequences of his action, for he is indeed a slum that cannot be renovated:

Thus Morrison gives us the final twist, the demolition of the run-down Hotel Harry Felix. In this final image, we see an emblem that could symbolize so much of Morrison's career: the exploding brain. It's a dark visual that reveals the absurdity of lifeiv, and the inevitable consequence of the battle between the mind and the body.

Throughout his years as a writer, Morrison has continually explored this idea. He repeatedly shows how the mind and the body are linked, and transcendence can only occur through a union of the two. In his outside-of-comics career, Morrison has delved into NLP, neuro-linguistic programming, which attempts to coordinate the relationship between the mind, the body, and the perception of reality. He's also become a chaos magician in his quest to understand these kinds of relationships. Within comics, he demonstrates these concepts again and again not just in the early work I examine in my book, but in later work like The Invisibles and The Filth (and Flex Mentallo and Vinamarama and Seven Soldiers, etc).

You can see that even in this very first 2000AD story, Morrison was a writer who used the comic book medium to explore his own philosophy of life. In a mere 2-page story, he established the mind/body theme that would drive his career for decades. And that, my friends, is why "Hotel Harry Felix!" is worth looking at closely.v

_________________________________________________

i "Future Shocks," staple strips in the 2000AD weekly, were very brief "Twilight Zone-esque" science fiction tales with twist endings. These 2 to 3 pages stories were used as training grounds for up-and-coming writers, and Morrison was just one of many all-star writers whose careers were launched from this platform (Peter Milligan and Neil Gaiman began with "Future Shocks," and Alan Moore wrote his fair share as well).

ii By 1986, Morrison had created Gideon Stargrave for Near Myths magazine, had written and drawn Captain Clyde, and contributed to Starblazer. I'm sure some of you may have read this work (or maybe not, since it's impossible to find in the U.S.), but it's pretty obscure stuff and it didn't launch him to prominence the way his work on 2000AD would.

iii Trust me, it's VERY funny.

iv I argue in my book that the major difference between the other great comic book writer, Alan Moore, and Grant Morrison, is that Moore is an ironist, and Morrison is an absurdist. That assertion was validated in a later interview I conducted with Morrison, and "Hotel Harry Felix!," as ironic as it might be, primarily presents an absurdist viewpoint.

v Morrison's later "Future Shocks"--and he wrote about a dozen before moving on to Zenith--explore additional themes and motifs which he would later expand upon in other works. "The Alteration," in 2000AD prog 466, for example, explores his ever-dominant theme of transformation, while Morrison's pop-culture and the apocalypse obsessions collide in "Alien Aid" from 2000AD prog 469. If you want to see more of my analysis on these early texts, let me know!