The conclusion of Kieron Gillen and Ryan Kelly's "Three" isn't as clean or cruel a statement as one might expect from a series about slavery, class oppression and Sparta, but that's chiefly because it avoids a neat, mythmaking narrative like those that its protagonists complicate and criticize. History in this series isn't just complicated by perspective, power and systems; it's also just plain stupid and unfair.

I don't want to get too spoiler-heavy, but it's tough to discuss the implications of a series' end without delving a bit into (you guessed it) the series' end. Like many readers of "Three," I really wanted the Helots to have some sort of epic victory -- and Gillen does give Klaros a terribly powerful opening. However, he tempers this success with some more realistic reactions from King Agesilaos.

Because when it's to their advantage, the Spartans are positively un-Spartan: retreating, scheming and refusing to engage. Terpander can insult them, and Klaros can challenge them, but the Spartans are always in control. The most the Helots can do is goad those in power to respond; the powerful still get to set the nature and timing of that response. And when they need to, they can choose to respond in open contempt of their own martial principles, because the principles weren't really the point anyways. The power that came from them was.

It's gut-churning to read. The past four issues have shown that it takes the Helots such courage to speak up against their masters -- and now, even when they've summoned that courage, it turns out that the masters don't have to listen.

Still, Gillen gives in a bit and provides a halfway happy ending. Rather than feeling like a cop-out, Damar's escape feels like a complication, because it gives the story two modes of victory. In some ways, victory here is about who gets to speak and be seen, but it's also about who gets to survive. Klaros and Terpander both get to make a statement, but they die. Damar hides, but she lives.

When writers mythologize oppressed people, they run the risk of suggesting that the real human beings who lived in that system were somehow lesser if they kept their heads down and stayed alive. In "Three," there is no shame or guilt in surviving. The last image the reader sees of Damar is happily tucked in bed, promising her children, "You're free"; the last image of the Spartans is a dying man on a foreign riverbank. It's beautiful without being cheap.

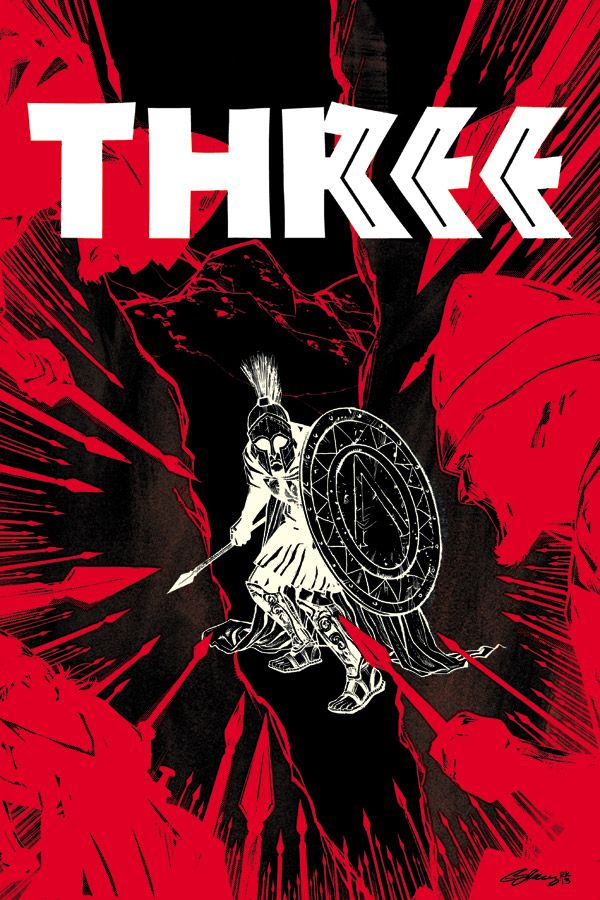

I could talk about the themes at hand for 10-12 days, but I'll stop because the execution deserves just as much space. I've read many series with a great sense of movement -- fluidity, drive, etc. -- but few that have "Three's" sense of moment. It moves like a drumbeat. Nothing flows quickly from one panel to the next; rather, each panel is a strong, distinct beat. It makes for heavy storytelling, amplifying the dread or importance of every action. When a series is only five issues long, it needs that to make an impact.

There's a joke in here somewhere about how you probably didn't cover the Helots during your sixth-grade unit on Sparta either, but I'll abstain. If you were unlucky enough to miss out on "Three" month-by-month, you should really pick it up in trade. It's been phenomenal.