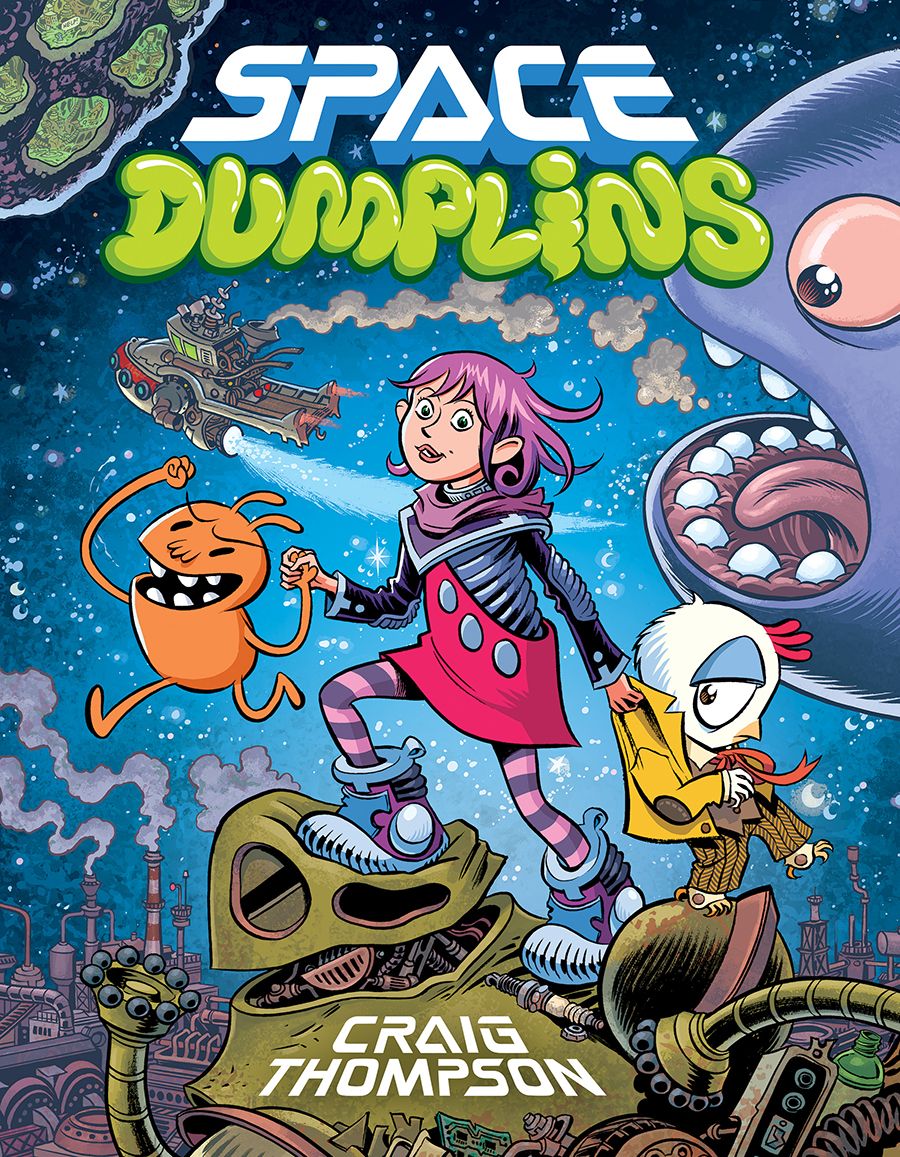

While he's best known for his emotionally mature and graphically complicated graphic novels "Blankets" and "Habibi," cartoonist Craig Thompson has a long history with all-ages comics as well. This August, Thompson joyfully dives back into that arena with his latest -- "Space Dumplins," from Graphix/Scholastic.

In "Space Dumplins," young Violet Marlocke's father -- a lumberjack in an outer space energy crisis -- goes missing while on a dangerous job. To get her father back, she bands together with similar outcast children and embarks on a high-flying, fast-paced rescue mission. It's classic all-ages adventure fiction stuff -- but this is Craig Thompson, so readers can expect more than one level of depth below that gossamer surface.

With his latest work, Thompson's ruminating on class divides, the energy crisis, environmental decay and the world we're leaving for our children. None of those themes will stop you from enjoying the excitement of the ride, but Thompson clearly hopes readers take more away from the experience. The cartoonist talked with CBR News about how everything -- from the characters' very names to the scatological nature of their fuel crisis -- make this outer space vision a reflection of the world outside our windows.

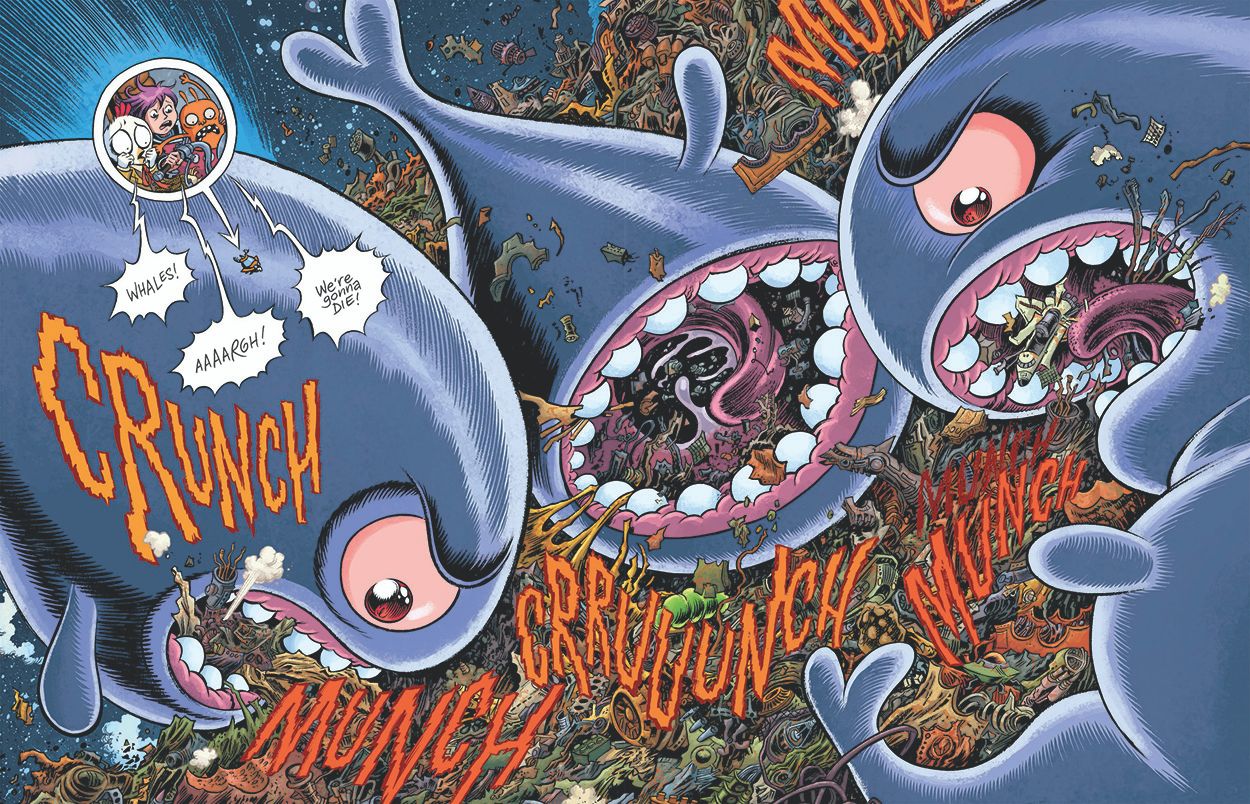

CBR News: "Space Dumplins" deals with an energy crisis, which is certainly a theme we can recognize from the world around us. But when did feces -- from space whales, but still -- become the major fuel source of the story's world and, besides the chance for logging puns, what made you run with that idea?

Craig Thompson: Space whale poop feels like a perfect embodiment of "dirty fuel" and the interconnectivity of energy usage and waste, issues that are becoming far more obvious domestically with the proliferation of shoal extraction, mountain top removal, offshore drilling and the Keystone Pipeline.

The fact that the excrement comes from space whales is a nod to [Herman] Melville's examination of the whaling industry. You mention logging puns, too, which was an element of Northwest history (I lived in Portland, Oregon, for twenty years) that I wanted to explore. But perhaps, most of all, kids -- of all ages -- love scatological humor.

While Violet has a good relationship with both her parents, she is clearly a daddy's girl. Can you give readers a sense of their bond?

The book opens with Violet's father secretly giving her spaceship driving lessons, which her mother would never approve of. Her mother, however, is instilling similar messages in her daughter. She wants Violet to know there's an entire galaxy of possibilities beyond the limited confines of their "trailer park" and the poor shantytown communities in the asteroid belts. Both parents represent hard work ethics, but through different approaches: physical labor vs. creative industry.

Craig Thompson Discusses "Habibi"

Violet's mother is named Cerulean, a hue of blue, and her father is named Garnett, a hue of red. Politically, they could represent "blue states" and "red states" and the half and half divide in our country. Violet, to me, is the perfect blend of both their energies. Her bond to her father is close, of course, so that it's desperately vital that she leaves on a mission to find him when he disappears in the line of duty.

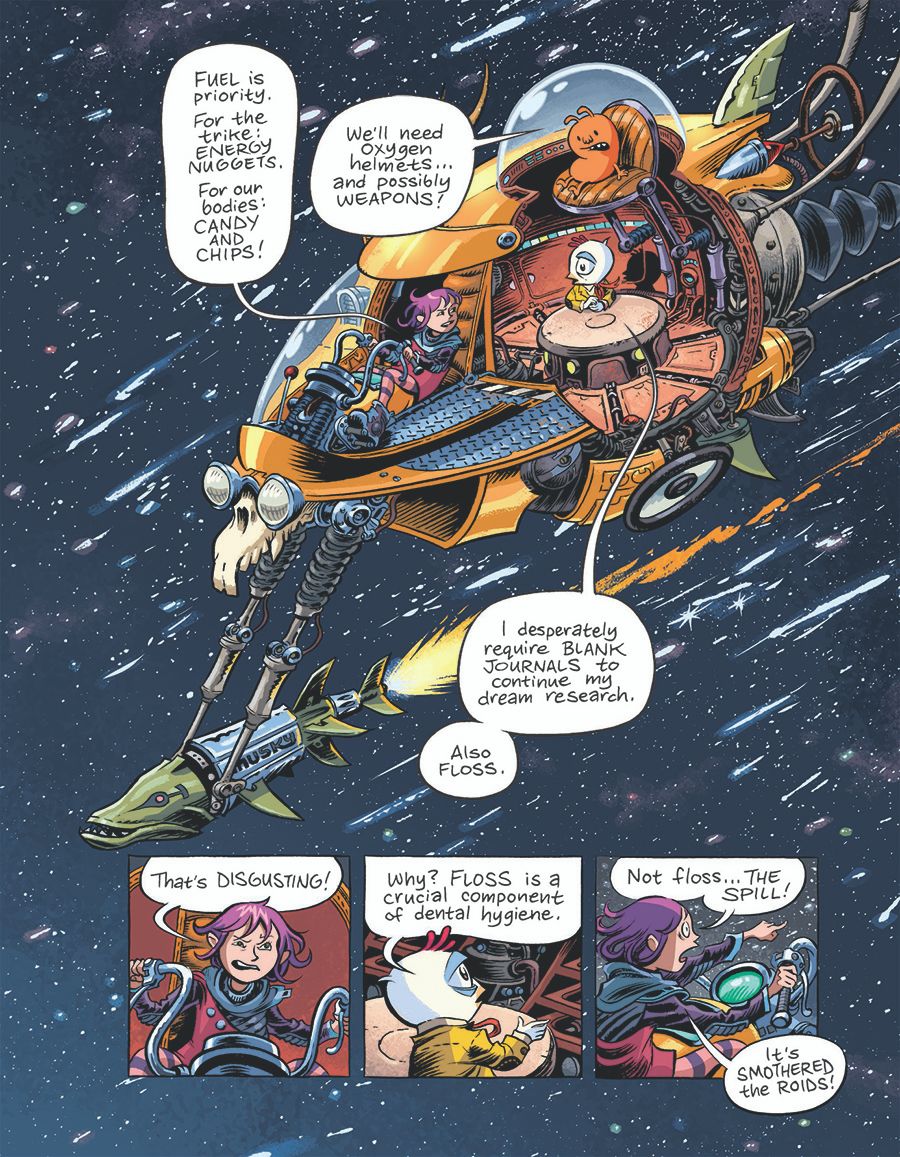

When her dad goes missing, Violet's rescue crew is rounded out by Elliot and Zacchaeus. Zacchaeus fills the diminutive rabble-rouser with deep-seated confidence issues role, while Elliot is a bookish chicken whose seizures give way to prophetic visions. What binds these three together?

Zacchaeus and Elliot mirror the social class dynamics of Violet's parents, which may be why she's drawn to them. Zacchaeus, impulsive and aggressive, is an orphan living on an interstellar garbage dump. Elliot, sensitive and esoteric, is a sort of a trust-fund kid raised on an elite space station. What binds all three kids is that they're lonely... and misfits, too -- but Violet is the only one optimistic and sociable enough (not to mention, heroic) to get these disparate personalities to cooperate.

Although "Space Dumplins" never loses sight of being a good-time, high adventure, you ground Violet's family in some socio-economic reality. Throughout the book, there are clear cases of the haves versus the have-nots, which manifests in a number of ways: the depiction of trailer park living as opposed to the high-tech space station lifestyle, the fancy schools and the dilapidated schools, Violet's snooty friends and her new, down-in-the-mouth gang. Was this a case of looking to add some subtle meat to the story, or were you simply trying to ground Violet and her friends in a believable ethos?

The class divide themes are the most personal elements of the story for me. I grew up poor working class, waited in government food lines, didn't graduate university or know people who had, saw those around me slipping through the cracks... Somehow, through my creative career, I've transcended those limitations and now live a privileged life of organic food and academic friends. Yet a frustration lingers of the vast social class divides in our country and around the world. I'm sure I have several more book projects ahead to examine this issue, but "Space Dumplins" touches on it in a subtle -- and strangely humorous -- way.

There's an interesting dynamic with Violet's parents -- her mother, a designer, is trying to get them into a more refined living situation, while her father is more blue collar and doesn't trust the shiny places. Violet is always a bit of an outcast because of her background. Is that part of the reason she prefers her father's physical lifestyle?

Violet is lured by the fancy technology and shiny sophistication of the space stations as much as anybody, but she's foremost an outdoor girl, and her outdoors just happens to be outer space. She's restless and wants to explore the galaxy and can't fathom why someone would want to shelter themselves from all those possibilities for adventure. It's the station children, in their name-brand uniforms, that reject Violet. But instead of crumbling or moping, she reaches out to other rejects and fosters a family.

Although your first graphic novel was an all-ages book, your last two efforts were decidedly more mature. What brought you back to all-ages?

My first book -- "Good-bye, Chunky Rice" -- was not deliberately all-ages, but it was written by a 21-year-old. While creating that book and "Blankets," my living was made drawing comics and illustrations for kids' magazines like "Nickelodeon," "Owl," and "National Geographic Kids." When Pantheon paid me a book advance for "Habibi," I no longer had to do illustration work to pay the bills, but I missed the side of my creative personality that created full-color cartoony work aimed at kids. "Space Dumplins" allowed me to get back on that wagon -- and to give back to the ten-year-old in me that first fell in love with comics. Those young readers are the future of this medium!

"Space Dumplins" is still a very different beast from "Good-bye, Chunky Rice," in that it's less melancholic and more sci-fi adventurous. How did this book come about?

"Space Dumplins" draws on all the things I loved as a ten-year old: Star Wars, "Goonies," "Ghostbusters," Dr. Seuss, "Calvin & Hobbes," Saturday morning cartoons. So there is a surface appeal to the book that's very accessible, a sci-fi, adventure comedy, but, really, that's just the framework. The meat is about environmental crisis, the class divide and forging a family that is global rather than insular.

Before sending Violet off on her quest, you spend a lot of pages establishing the dynamics of their world and her family situation. How did working on the action-packed "Space Dumplins" compare to more mature fare like "Blankets" or "Habibi"?

Each of my books is all-consuming, and I throw myself into them completely, so "Space Dumplins" is definitely on equal footing for me, creatively, as "Blankets" or "Habibi." After "Habibi," I'd hope to take a break from the intricate detail of arabesque designs, but "Space Dumplins" proved to be just as detailed -- only in spaceship mechanics and alien worlds, exactly the kind of detail I loved to get lost in as a child.

What are you working on next? And how epicly long will the next book be?

The next project is a collaboration with the 73-year-old French comics master Edmond Baudoin, working title "Drawing Brothers." It's equal parts "Blankets" and "Carnet de Voyage," a more improvisational project that allows me to loosen up my ink line again and paint a portrait of real life rather than craft fantasy worlds in my studio. It'll probably be about 300 pages, but thankfully Edmond is drawing half of them!

"Space Dumplins" is in stores now.