The comics business is a social one. Yes, a great many of us creators sit in a room alone all day, by ourselves, doing what we do. Maybe that's one of the reasons it's such a social industry; we're all starved for human interaction. So when creators do get together -- at restaurants, at bars, at conventions, even over social media -- talk turns to craft and credit and complaints.

I guess that's the same as almost any other business. But a constant thread running through comic conversations is how do we get better. How do we, as individual creators, improve our game? Those conversations, as well as recurring questions about writing I get at conventions and signings, prompted this list: seven DOs and seven DON'Ts for writing comics. These are, by no means, the only things you need to know. But it's not a bad place to start.

1) DO hit your deadlines. This seems an obvious one, right? It's really the biggest necessity of the job, especially on a monthly series. It's a deadline-driven business, and if you can't turn in your work on time, the editor will find someone who will.

DON'Ts

1) DON'T disappear. If you're going to miss a deadline, fess up. Better yet, let the people you work with know ahead of time that you're going to be late. Don't duck emails and texts and phone calls from increasingly irate editors. Avoiding a rough conversation is a recipe for disaster. It's the fastest way to gain a reputation as unreliable... which is the fastest way to make certain you're not hired again.

2) DON'T treat the lettering draft as a first script draft. This plays into turning in clean copy. When you turn in a script for lettering, it should be what you want printed. Yes, there are tweaks to be made here and there on a lettering proof, but it should be only tweaks. By far, the most common complaint I hear from letterers is writers and/or editors who use the lettering as a first pass, and substantially rewrite an issue once it's been lettered.

Letterers get paid once. If you're making a letterer re-letter the majority of the issue to suit your whims, you're stealing both time and money. if you as a writer can't envision your script lettered on the page without actually seeing it on the page, you're missing an important tool in your toolbox.

3) DON'T bleed in pages. One of the consistent gripes from artists is receiving script pages via drip feed. Delivering four pages of script at a time, sometimes even just one or two pages at a time, hamstrings the process. The artist cannot approach the story as a whole, and thus can't create a cohesive issue from a layout and design perspective. And, to be honest, bleeding in script pages is also kind of insulting, a backhanded way of saying the artist isn't important enough for you to buckle down and finish the script.

Now, to be fair, I've done it myself. Most writers have, at one point or another, when deadlines collide or extenuating real-life circumstance arise. It happens... but shouldn't it be a habit.

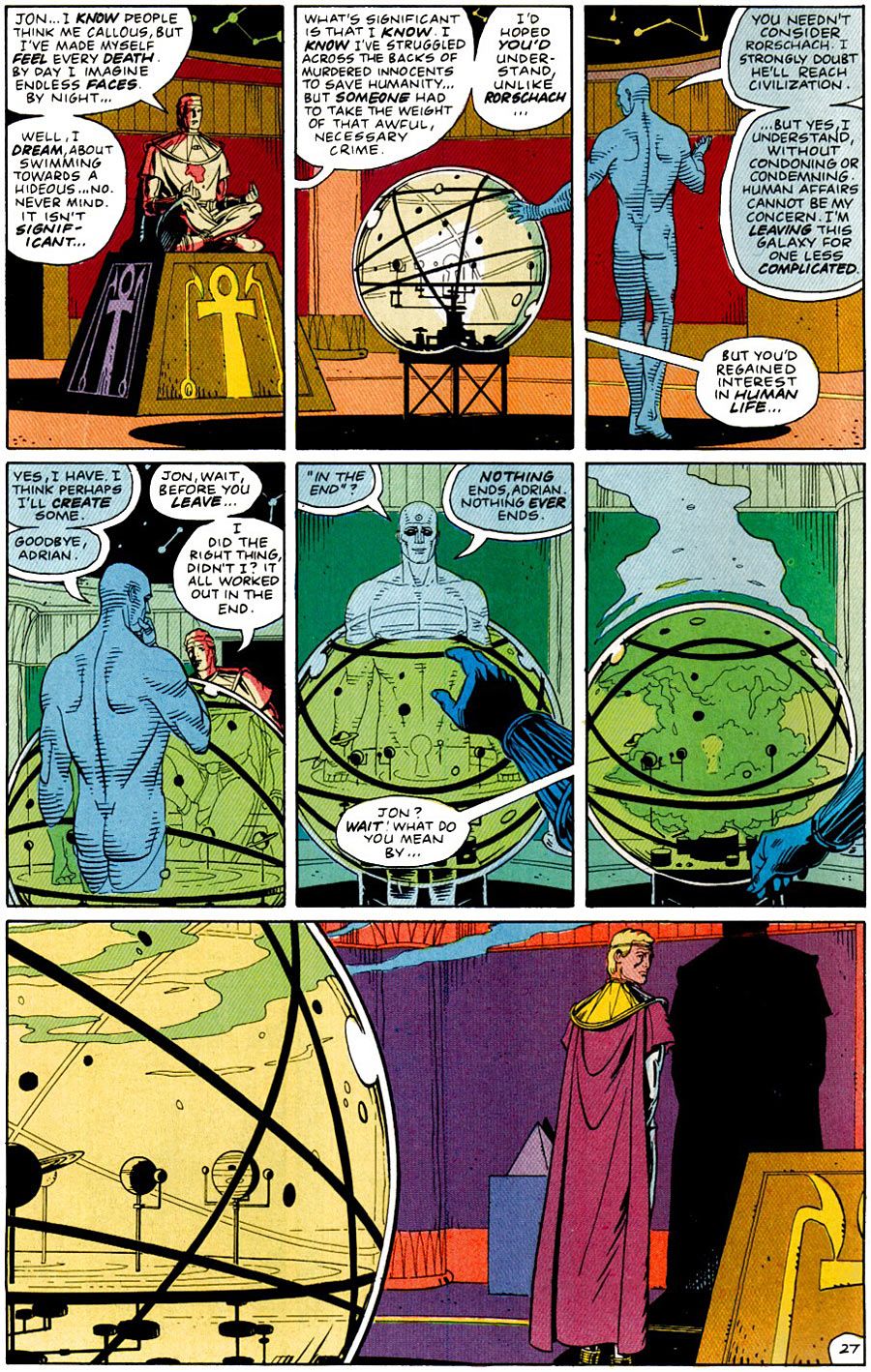

4) DON'T forget you're part of a team. This extends to being part of the creative team, as well as being part of the larger effort in a work-for-hire situation. A creative team in comics is like a jazz combo, or a basketball team; the individual players do their own thing, but riff off of each other to greater a greater whole. There's no true success if one player or piece is diminished. Part of doing your job is to help everyone else do their job.

When you're writing work-for-hire stories, you're playing with someone else's toys, in someone else's sandbox. The characters and concepts are not yours, you're simply being allowed to use someone else's property. That means you must come to grips with the fact that you're not in complete control. The editor, and by extension, the company, have the final say. You're more than a puppet on a string, certainly, but you're not autonomous. There's give and take, there's go along to get along. Pick your battles, but compromise is your friend.

5) DON'T think you're more important than anyone else on the team. You're not.

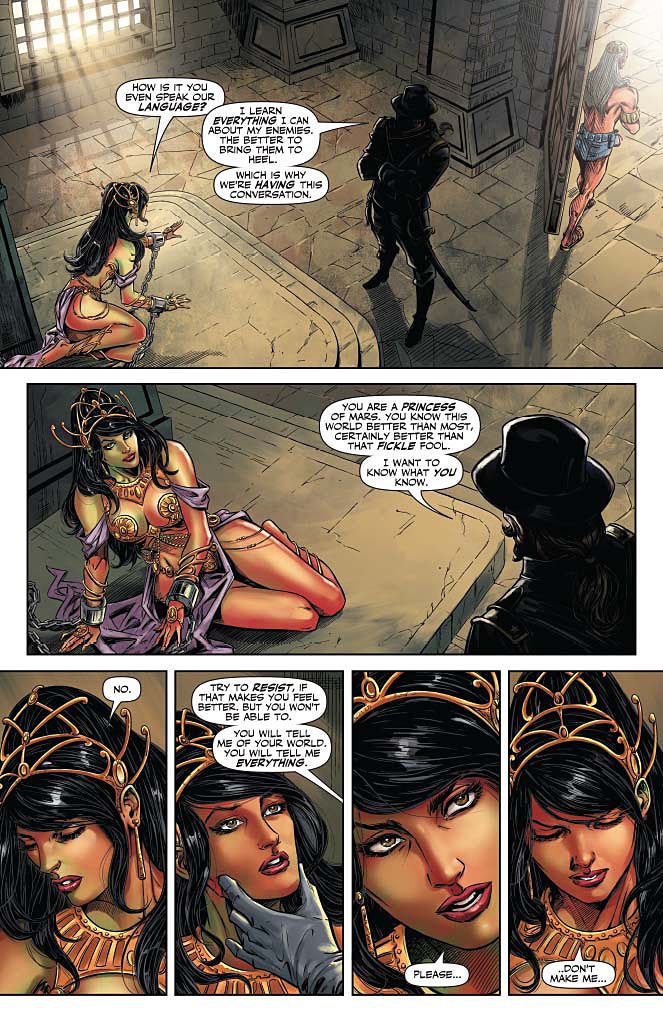

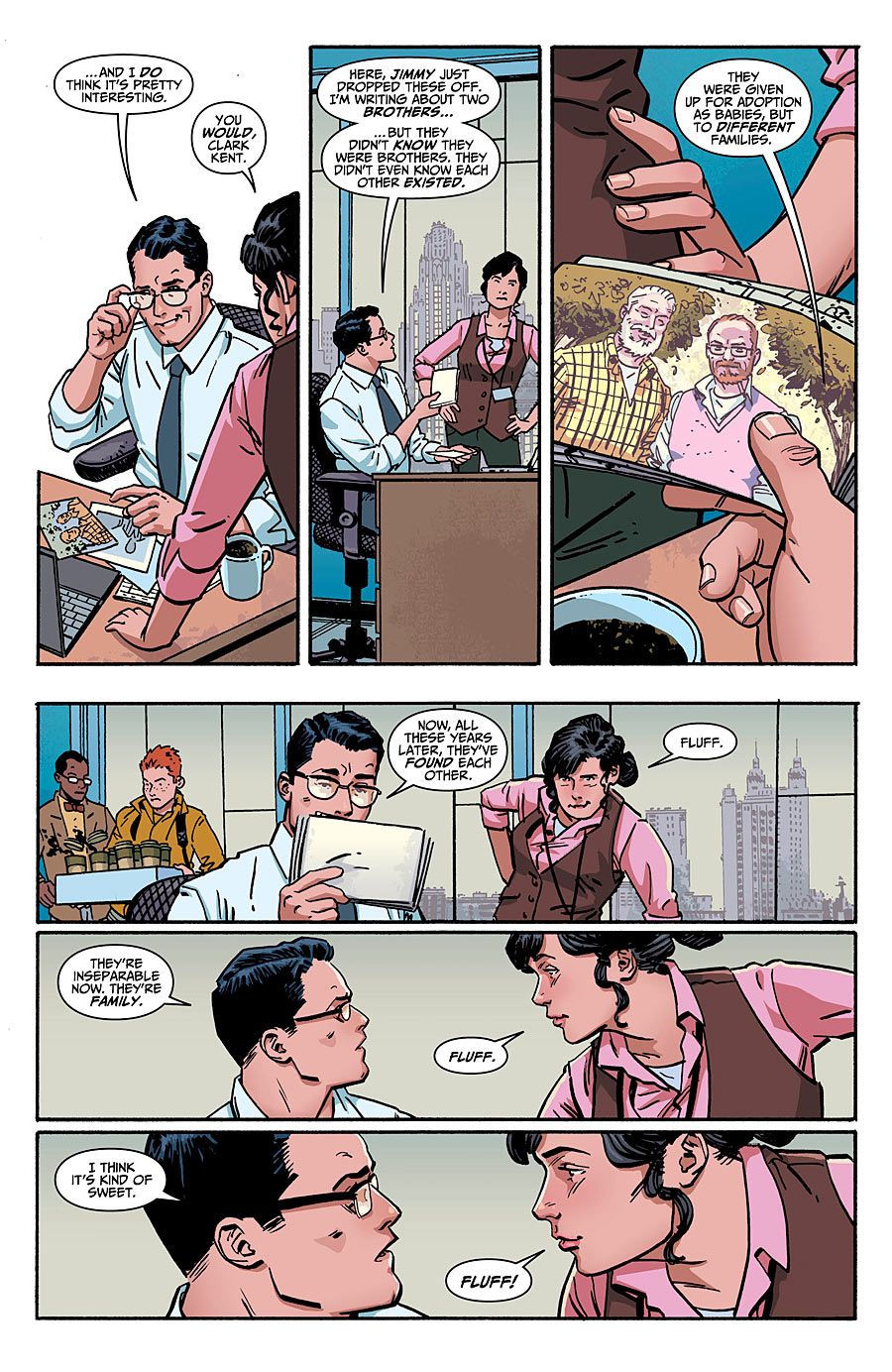

6) DON'T wallow in cliche, or drown in exposition. Short version: if you've heard it before or read it before, endeavor not to write it. How many times have you heard "Let's do this!" in a movie, or read it in a comic? Avoid cliche, come up with a new way for your character to say what needs to be said, a way that comes from that character, rather than a generic one.

On a related note, one of the most necessary aspects of writing craft is the ability to convey exposition seamlessly, how to weave background information into the fabric of your story. The worst line of dialogue you can write is "As you all know..." That means you're using one of your characters as a mouthpiece to explain to other characters what they already know. It's the hammiest of ham-fisted techniques.

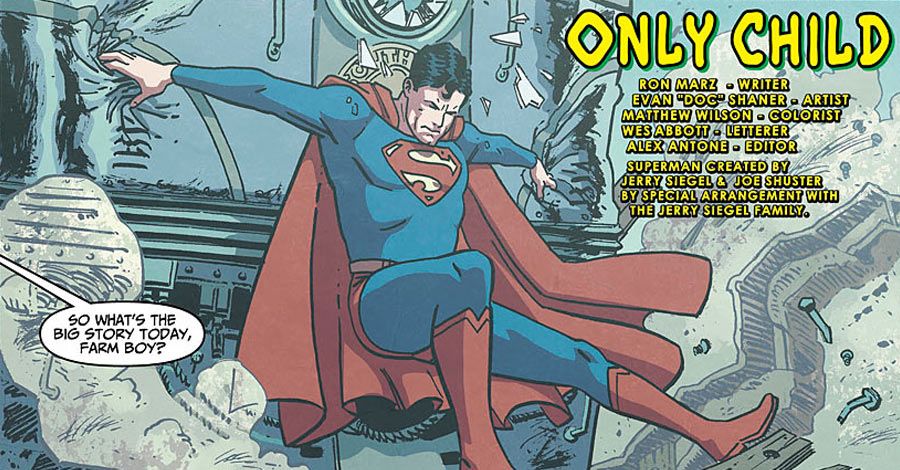

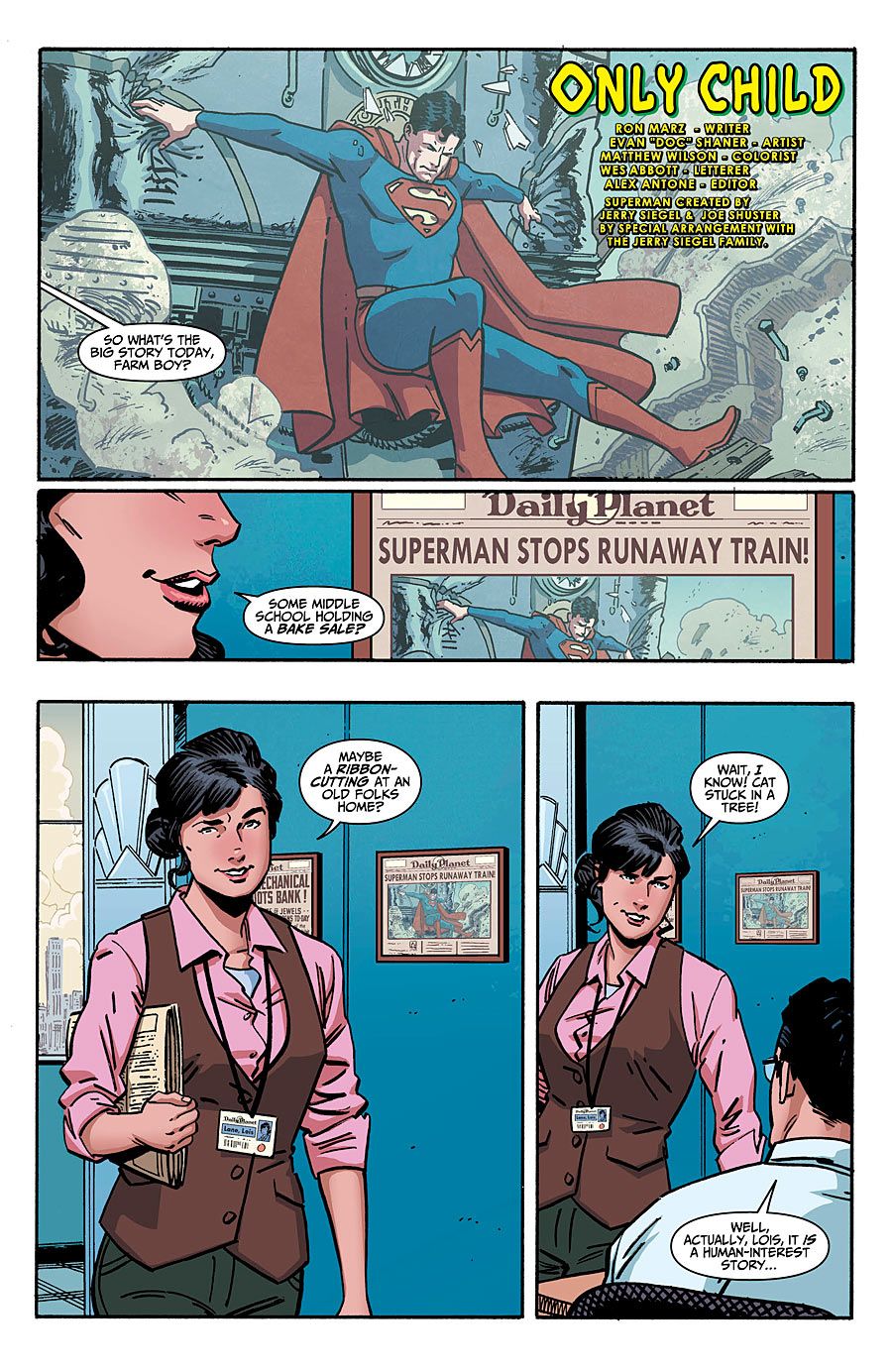

7) DON'T forget to mention your art team in every interview you do. Pretty self-explanatory. Also pretty simple from a common courtesy standpoint. But I see it all the time in interviews with writers -- not even a mention of the art team. Artist appreciation and credit lags far behind where they should be, in both reviews and features. The reasons for that, and how to fix it, is another column in itself. But at the very least, always mention the people you're working with, even if the interviewer doesn't ask. You're all in this together. Act like it.

Ron Marz has been writing comics for two decades, and thinks it's pretty much the best job ever. His current work includes "John Carter: Warlord of Mars" for Dynamite, "Skylanders" for IDW, "The Protectors" for Athlitacomics on Madefire, and Sunday-style strips "The Mucker" and "Korak" for Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. Follow him on Twitter (@ronmarz) and his website, www.ronmarz.com.