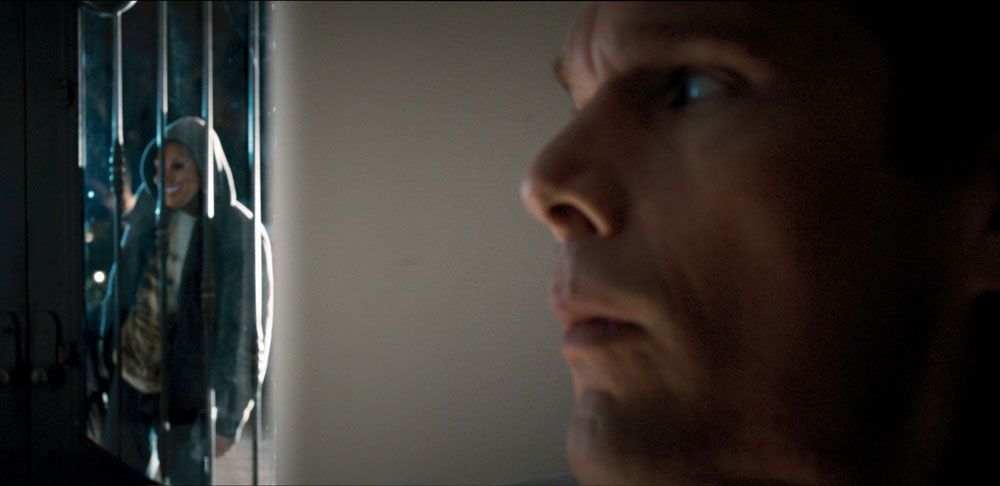

In director James DeMonaco’s The Purge, a wealthy husband and wife (played by Ethan Hawke and Lena Headey) fight to defend their family and their home when attackers descend upon them during an annual “purge” of violence that’s been sanctioned by a dystopian government. With Paranormal Activity and Sinister producer Jason Blum shepherding the film into theaters this weekend, its story guarantees stylish visuals and intense thrills. But what are the deeper ramifications of creating a society that allows the populace an annual 12-hour window to exorcise its rage?

Blum is willing to hint at the film’s philosophical foundations, but having already received feedback from across the political spectrum, he hesitates to draw any firm conclusions. “We made a really violent movie about violence in America,” he observes. “And the fact that people will talk about that after the movie in addition to being scared… was on the plus side in terms of deciding to go forward with the movie.”

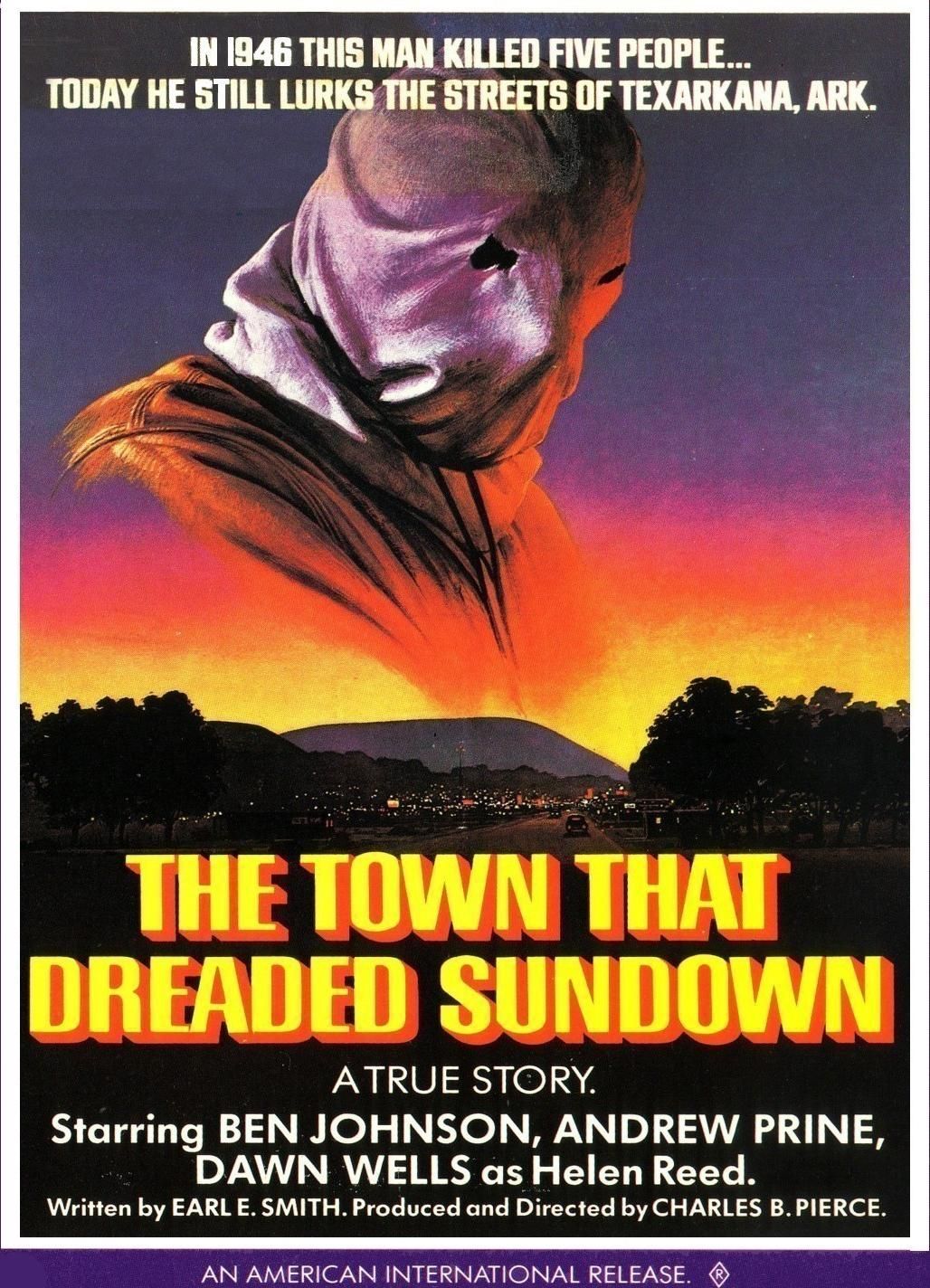

Spinoff Online joined a small group of journalists at the film’s recent Los Angeles press day, where Blum discussed the process of developing this creepy cautionary tale. In addition to examining some of its core ideas, he revealed his approach to creating compelling horror, and offered some updates about another future project, his forthcoming reimagining of the slasher-movie classic The Town That Dreaded Sundown.

A couple of your next films are Insidious 2 and Paranormal Activity 5. Why do you think putting families in danger makes for a good suspense or horror film?

I think good suspense or horror is really about creating situations that are relatable, throwing a wrench in it, and watching people respond to that. The most honest responses you get to watch are in houses, in people's private lives. The most private space is in the bedroom, which is Paranormal Activity, or in your own intimate space. I also think that's where you feel safest, so when you're threatened in the place where you're the safest, it makes for the scariest situations.

What was your first reaction when you read the story?

I didn't read it; I heard it. James told me the idea, and what I loved about the idea was that when you first hear it, you're like, “That's crazy, that could never happen.” A lot of people go into the movie like, “I'm so psyched to see it because that could never happen,” and then, when I watch the movie with audiences, in the middle people are into the Purge -- they're applauding, and you're like, “Gah!” And then at the end of the movie, people kind of catch themselves and are like, “Ew, I'm not so psyched about how I was feeling in the middle of the movie.” And so, just to answer your question, what grabbed me about the idea is that on one level, it's very crazy and abstract, and on another level, we're having conversations like the one we're having now, like, “Maybe this isn't so crazy.” Not to say that it's good to have a Purge, but that maybe a Purge might happen. The fact that we can have those kinds of conversations is nuts, but it's a tribute, I think, to James and his idea, which really works on both levels. You know, they tried to make this movie as a more expensive movie, which I am very against. As you all know, I don't like expensive movies. But before I was involved, they tried to make it a more expensive movie and no one wanted to make it, for a lot of the reasons we're talking about here. And I think the idea keys into what we do, which is making movies for low budgets that are strange and different and entertaining and fun.

Do you think if society was given permission to use violence for a day, we would all find our inner animal?

I don't know? I just hope it doesn't happen. I hope it remains a movie, is what I would say to that. I think it would not be pretty.

Between this and Before Midnight, Ethan Hawke has two films coming out in the next few weeks that couldn't be more different. What made him the right guy for this type of material?

He and I have known each other for a long time. We've been friends for 20 years. He was very resistant to doing a horror movie, and I spent a long time talking him into Sinister, which he finally agreed to do. And he liked it so much that he came back and said, “Yeah, let's do another one.” And that's how we did The Purge, which doesn't answer your question. I like to work with actors who are not normally in these kinds of movies. I really like to work with theater actors. Theater actors tend to do lots of independent movies, and those are the actors that I like. I don't always work with them on these movies, but I really tend to try -- you know, Patrick Wilson and Rose Byrne in the first Insidious -- I try to work with people who you're not used to seeing in scary movies. I think it makes for a more interesting mix when you're watching the movie.

One of the things that makes the film more intense is a lack of clarity in terms of the geography of the house, for example. When you’re conceiving something like this, or, say coming up with a reason why people are filming in the Paranormal Activity movies, how important is it to explain those things and at what point do you just go, it’s less important than scaring the crap out of audiences?

Well, those are two very different questions. Paranormal Activity is found footage, and the key of every found-footage movie is why are they filming? And it’s a nightmare question to answer. Although found-footage movies are much more production-friendly, storytelling-wise they’re way harder, because scary movies are all about building up situations where it’s life or death, and when there’s life or death, no one’s holding a camera. So that’s an incredible challenge, and when we work on making a Paranormal Activity every year, we work on that question harder than any other question – justifying the camera. I think a lot of the reason why people are annoyed at found-footage movies is because people look at them and go, oh, that’s easy, I could do that too. And production-wise, they’re super easy! Like you film, you don’t need lights, you just film! But storytelling-wise, they’re much harder than traditionally-shot movies.

The geography of the house in the movie, we did it on purpose so we thought it could make it scarier, but if your question is adhering to a certain logic, that is crucial for us. Like, every scene in The Purge, we said we want it to feel like, “What would you do in this situation?” We didn’t make it a future that seems like not tangible and so far away that they there are flying cars. We wanted a future that’s just a little far away so that it seemed very relatable to now, and that the people in it would do things that you or I would do. So as justifying the camera is to Paranormal Activity, I would say relatability is to The Purge in terms of the amount of storytelling energy that we put in those two things. Because I think that’s what makes the movie scary: the scares are the easier part of scary movies, but the hard part of scary movies is what leads up to the scares.

What kind of concern do you have as a producer about how audiences might interpret this material?

I was into that. I love a high concept. I loved that first of all, it was a great high concept scary movie. I loved that James chose to set the movie after the Purge had taken place seven times or eight times so there's nothing unusual about it. It's been an American tradition for many years. So I loved how the movie worked on that level, and then there are definitely social themes in the movie. I don't think there's a message in the movie, specifically, because everyone that I've shown the movie to -- some people rightwing, some people leftwing -- one interesting thing that happens is whatever political party you're in, you come out of the movie saying, “See, that affirms my beliefs.” I thought that was cool. People on the right would be like, “The Purge is a terrible thing and this is an example of big government invading our private lives when they should be smaller and get out of our private lives.” People on the left say, “There are too many guns, and this is what happens when there are too many guns.” For me, I guess the short answer to your question is we made a really violent movie about violence in America -- and the fact that people will talk about that after the movie in addition to being scared, I wouldn't say was a concern, but was on the plus side in terms of deciding to go forward with the movie.

Some of the journalists who saw the film with me noticed the film shows us the worst in us. Was that the goal of the film?

I don’t think we set out to do that, but I think that is a lot of what the movie does – what is the worst side of human nature? If there was a purge, would the worst side of human nature come out? Who knows? I have no idea. I mean, I think psychologists can answer that much better than I could. But yeah, definitely, this is a very negative interpretation of what could happen if there was a purge, with our species.

Could you boil down the moral -- especially the violence? In one sense, you get an anti-gun message, but on the other hand, the homeless guy stopped the violence --

– with a gun. Yeah. Again, my point of view is probably different than James, who wrote and directed the movie, but I wanted to get people talking just like you're saying. Are they good? Are they bad? Is this what happens when gun control gets less? Maybe this isn't such a bad thing? I personally think the Purge is not a good thing. Like, I'm not advocating for a Purge, and I hope that -- I should say, I'm 99 percent sure -- we'll never wind up with a Purge ourselves, and I think that's a good thing. But we weren't coming at it from a specific, political point of view. It's supposed to get people scared and to get people to have a good time for an hour and a half in the movie theater. And if it also gets people to talk about whether this is a good thing or a bad thing, that's great, too.

Over the weekend, I got to rewatch The Town That Dreaded Sundown, and I understand that it's a metatextual remake. Given the fact that it's so bizarrely uneven in terms of its tone, what prompted you to remake it in the first place, and what are the obstacles of making a horror movie in a world where horror movies exist, post Scream and Cabin in the Woods?

Ryan Murphy found the film and brought it to me and said, “I want to do it.” I think he is an amazing creative force, especially with American Horror Story. I think he thinks about horror in a really neat way. He pitched it to me and I really wanted to work with him -- I didn't know the movie. That was first, that's what got me interested in it and I have a really good working relationship with him. But secondly, the whole point of why my business exists and why I'm such a fanatic about making movies inexpensively is it gets you to different stuff. The same relationship I have with The Purge, I have with The Town That Dreaded Sundown. Every single thing you said, we've thought about. I'm like, “Let's try it.” That's the fun thing when you don't have a $20-million horror -- which is a typical horror, movie-studio budget -- or a $180 million tentpole budget looming down on you: You can try new stuff. And it might work, it might not work, but the fun is that we can try. It's a really weird movie to remake, and I really like doing weird things.

Is it safe to assume that you guys will be jettisoning all the Keystone Cops stuff?

Uhhhhh. I think Ryan would be very upset if I answered that question.

Talk about the differences between low-budget and high-budget filmmaking. What kind of creative decisions does that dichotomy facilitate?

A lot of different ways. When you have a limited amount of money, you can’t spend a lot of time on visual effects, on stunts, on all of the bells and whistles, but it’s like, if you have a choice when you’re prepping a movie and you have a choice of like, I can go to ILM and look at the tests of the spaceship or like sit in a room with my actors and talk about story and their character, it’s kind of more fun to go to ILM. And I think that happens a lot – I think that it’s more fun with the effects and the explosions, like I’m going to go look at a pre-vis of my hotel exploding. That’s fun. I would certainly rather do that. But if you take those things out of the equation, it forces the director and all filmmakers, and me too, by the way, I’m not pigeonholing directors, and a producer too, who loves to talk about how much blowing up a building is going to cost, to really focus on story and focus on character. And I think there are a lot of benefits to doing movies on a low budget. That’s one.

Another one is every single movie made is cast in reverse – the casting of movies is totally broken. So that when you’re a producer or director and you’re going to get your movie made, you’re not asking what actors would be good in these parts, but, okay, what actors get my movie made, regardless of the parts. And everyone says, “God, Jason, the acting in your movies is so good!” Well, I shouldn’t take credit for it because the directors pick the actors, I don’t. But secondly, your chances of getting good actors in movies are so much better when you’re picking actors that fit the part. When I first start working with a director, I always say, take the list that you got from your foreign sales agent, of the actors that make your movie go, rip it up, throw it out, don’t ever look at it again, and now pretend you’re in college and you’re directing a play, and think, what actors whose work you’ve either seen or haven’t seen would be great in this movie? So that’s another benefit. This is a whole another topic, but those are two big things that I think are tangential benefits of low-budget filmmaking.

Related: The Purge's Ethan Hawke on Our Fascination With Violence