Just as there's something romantic of the lone cartoonist hacking away, chasing a high, there's something fruitful of the collaborative writer/artist pair achieving unison.

Joe Casey, in his last interview with Tim Callahan, calls it "true alchemy," while Chris Claremont, for a forward of he and Frank Miller's Wolverine, describes it as "what all of us in comics strive for ... to create a whole which is much, much greater than the sum of the parts."

In essence, it's what Doug Moench and Bill Sienkiewicz found in Moon Knight, their 1980 Marvel Comics collaboration. Though it basically took 23 issues of growth to get there. Sienkiewicz had to work through his Neal Adams phase, as Moench recalls in this interview with Charlie Huston, and Moench, though I can't prove this necessarily, seemed to write, at first, like any other scribe in the Bullpen - throwing text over the visuals, overcompensating, ignorant of the visual caliber at hand.

Though those early issues still zing in a particular way. The stories are tight and colorful enough to propel a reader through the experience (Moon Knight fights a ghost story, for instance), and knowing two makers are up against the Jim Shooter-rhythm of super hero comics, working to achieve Art within those confines, while still performing for and feeding the monthly Marvel fiend, makes the entire Moon Knight run all the more endearing to read. Because it becomes, in hindsight, mind you, this passion project disguised as a job, and it revolves around a d-list villain published by a corporate outlet, where even the editors seemed in support (Ralph Macchio and Marv Wolfman were considered big fans, pushing for more stories of the character).

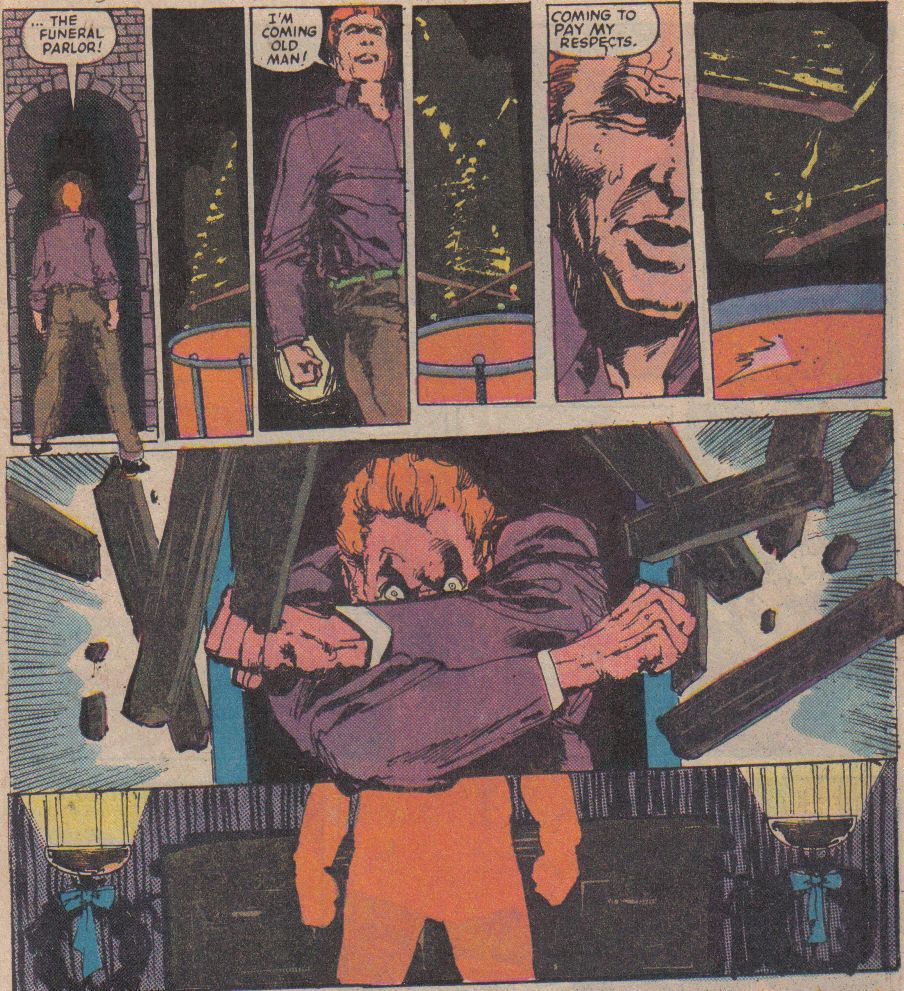

All of this reaches its peak between issues #23 and #26, where Sienkiewicz gained the confidence and brushed off the Adams impression, no longer giving any fucks as to what traditional super hero readers thought. And as that happened, Moench took notice and wrote his narration to work with rather than over the cartooning. Again, all in the confines of the monthly Marvel Comic, with a caper to solve. Though #26, the classic "Hit It" issue, transgresses against this, a bit, reading more like a modern day art comic, contemplating something.

It's a famous issue for a certain crowd, and as topical as it is (child abuse), it's easy to understand why. The book, released in December 1982, came out right in those budding years in which readers yearned for "darker, serious" narratives involving their favorite childhood icons, as if to somehow justify their significance. And "Hit It" 's critical success may have even argued a place for more of it.

Yet that's not why I enjoy the book. If anything, I find the subject matter, at times, overpowers the work, giving off this lecture instead of an observation or thought. I mean, considering Sienkiewicz's connection to it (he later admitted he'd been abused as a child), there's something of "Hit It" that feels urgent, but the dialogue tends to burrow the thing back, shifting the comic more towards parable than something we happen to see and make sense of. Lines like "There's been enough hitting tonight. I won't add to it." come to mind.

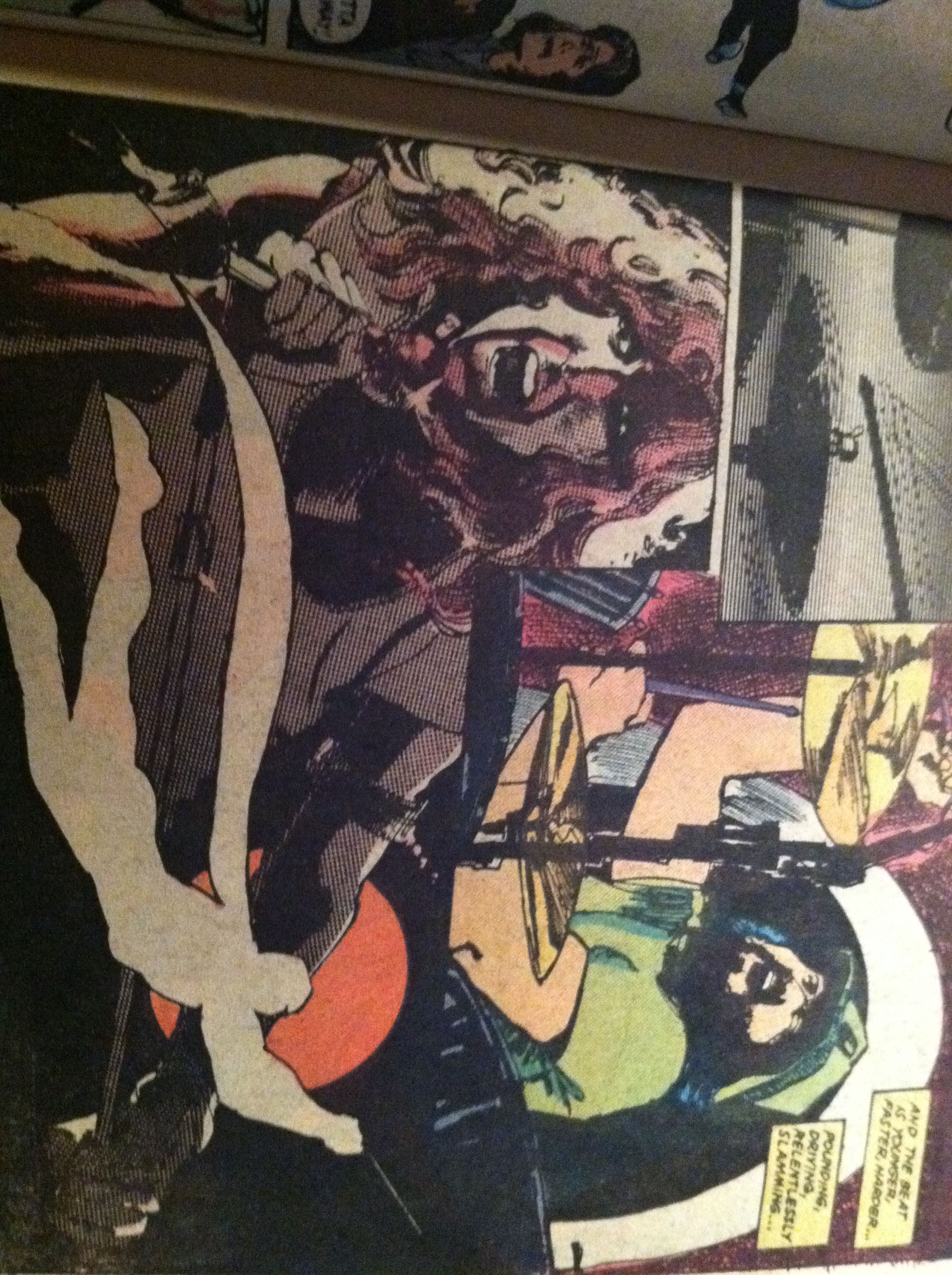

Though there's a music metaphor/motif floating through "Hit It" which offers the main idea without being so overt, as well as presenting, in the purest form, the Moench/Sienkiewicz collaborative act.

Moench always intended for the story to have this element (a way to show violence rolling on like a drum beat), but originally, in its 7-page form, it was less apparent, until Sienkiewicz, you know, "went nuts," taking the thing in his own direction. From it, comes this seamless mesh of dreamed rock 'n' roll imagery and depicted plot, sealing both a meditative tone and the marriage of the two makers.

Moench, in that Charlie Huston interview, recounts the making of "Hit It".

"That was supposed to be a seven-page backup story. So I did a plot that would fit in seven pages, and Bill went nuts. He went berserk. He blew up all these giant panels and extended the thing. They had me crammed into this tiny little room with a typewriter. I did it on the fly right there, right out of the typewriter. Thankfully it was a stream of consciousness style. I’d never written anything faster. And they were literally ripping pages out of the typewriter and taking them over to the bullpen to have it lettered right on the spot."

This account shows how "Hit It' went between Moench and Sienkiewicz, starting as a question, spurring something complex and forcing the one who asked to respond accordingly. It's two-way, answering something outside the egos, beyond the figures, and forcing those in the discussion to meld their perspectives in order to find it. Though oddly enough, they come completely around, and show their own finest efforts here, realized after two-dozen issues of Marvel formula. Seinkiewicz in his own style; Moench writing with, not against his compatriot.

The comic's loose, free-verse narration, which reads more from the POV of the book itself than any particular person or character, creates an entirely different effect. The bits swing with the drawings of Moon Knight rifting across Manhattan rooftops, offering colorful asides and etching further detail into the visual depictions, yet they address Moon Knight, as well. Jabbing him at first (Now, don't be late, Moon Knight), and later begging him not to attack his attacker, the ravaged victim ("No, Moon Knight. No!"), as the issue concludes. It echos like the last, desperate plea of a betrayed parent, who at one time believed more was capable of their child.

One could argue Moench as the real culprit of these narrative bits, because let's be honest, he did write them, and as the character's co-creator, he could be seen as the protagonist's "parent." Though the way in which the narrator bounces with Sienkiewicz, in this eerie unison, as well as sounds - like this lively, omnipresent force - doesn't support the claim. It spills from its source in real time rather than appear orderly like a prepared statement given by some speaker, and it feels intended as to not give the storytellers any possession of the piece, but the piece possession of itself, as if sentient. Because if they wanted possession, I would think there'd be more authority in the tone, yet instead the narration reads neutered, like the force behind it cannot intercept.

The character's transgression and split from the text (No, Moon Knight. No!) suggests a certain independence as well as powerlessness at the hands of Sienkiewicz and Moench. Even Sienkiewicz's drawings only seem to follow and slip between events in the comic's reality instead of present what he chooses to see.

It all ties back, I think, to the comic's central theme of nature repeating itself, no matter how desperate you may want to shift the curve another way.

Which sort of says something of comics, right? No matter how much one party may wish to make it about either art or story, it's ultimately a marriage of the two.

A balance.

It all comes back to fucking balance.

Alec Berry hates this piece. Follow him on Twitter @Alec_Berry.