The Open

Mardou produced one of my favorite comics of 2013, The Sky in Stereo #2 (which you can read about in this column). I'd describe it as warmly tactical, servicing the story at every angle, with a inevitable sense of damage guiding its tone. This interview should shed a little more light on this cartoonist, who's been producing work since the early 00's. We begin out conversation, by phone, on the subject of Manchester, her place of origin.

The Feature

Alec: So let’s just start at the beginning. Tell me about Manchester because I know nothing about it.

Mardou: Well, I can tell you about Manchester like 10 years ago, which was the last time I lived there.

A: That’s fine.

M: What’s it like? It rains a lot. It’s like 30 miles from these hills, so that means it’s constantly raining a lot and overcast. It’s kinda like Portland, Oregon, you know? People go to the pub a lot, so people drink a lot there. I don’t know, you just have to stay cheerful. People are really ... quite friendly, for the most part, and ... hmmm ... it’s kinda hard to say. It’s a funny question. People are friendly in this like northern way that you have in England. It’s much more friendlier than the south, like London.

It’s a good place to be a young person. It had a really great music scene. When I was still in school there were so many great things going on. Like the Happy Mondays and Stone Roses were really big, and you felt that you were living in a place that was culturally important. And before that, there were other bands that I was starting to become familiar with, like Joy Division and The Fall. I’m a big fan of The Fall. And soccer is a big thing here; we have two really good soccer teams. So I always felt that Manchester was kind of an important place even though it’s kinda ... it’s not London, you know? It has this underdog status. We know we’re the crap-like, underdog city, but we have, like, loads of things to brag about. It’s this good place to be from.

A: When did you start drawing?

M: Well, I drew as a kid, like all kids do, and then I stopped, like most people do (laughs). But when I was 16, I got really into Deadline [a comics magazine created by Steve Dillion and Brett Ewins].I’m not sure if you’ve heard of it. It’s where Tank Girl got its start. People like Jamie Hewlett and Nick Abadzis, who’s actually now a friend of mine, but he was doing Hugo Tate at the time. It had a lot of music bits in it, as well. It had a nice crossover appeal, and it was really appealing to me because I was just getting into indie music and stuff. It exposed me to a lot of artists, and I was taken by that. I was like, “I really want to do this,” you know?

So I started drawing comics when I was 17, but didn’t get very far. I discovered how difficult it was. It was fun to do the drawing, but writing a story, and making it work, was so difficult, so I gave it up until I was about 22, at my last year of university. I started then putting together another comic, seriously. I worked with a friend and we did a comic called Stiro. He wrote it, and I drew. I’m kinda embarrassed to look at it now, but it was a good way for me to learn how to make comics. I mean, it was so derivative – like so many other comics. I was into Eightball and Hate at that point. They were like my two favorite comics, so what I was doing was like derivative of Peter Bagge stuff, or trying to be like Dan Clowes. But, you know, that’s how I was learning.

A: What’d you study in college?

M: English Literature.

A: So when you graduated, did you just look past the degree and decide on comics?

M: I decided to just really do comics. I mean, that was always a really present thing. I left college and didn’t really have much direction. I ended up working in a bookstore and then a library. But it was always, you know ... I didn’t really have any career aspirations other than writing. At that point, writing had really started to become the thing I wanted to do and realizing that I had some stories to tell.

But yeah, I put out a bunch of mini comics. Three issues of Stiro. We only printed like 100 of them, 200 of them. I’d sell them. I used to work in a liquor store (chuckles), and I’d sell them to customers who came in there. So we had no idea of how to get our comics out there. The internet was around, but I didn’t really use it at that point.

Around 2004, I applied for an arts grant to pay for a comic called Manhole. They just gave me some money, like £500 – what’s that, like $800? – and I could print my first, solo comic book. That got more attention. In England.

A: Let’s go back for a second to when you were deciding on comics as what you wanted to do. Was there fear in that decision at all? You know, like trudging into the unknown?

M: No. Not really. It seemed like a wide open thing. I would go to comic stores and try to find stuff that appealed to me, which was like literary comics. I liked a lot of first person stuff or stuff that felt like novels. Like at the time, Daniel Clowes was serializing Ghost World and then David Boring, and I was so wowed by that. I was like, “this is exactly what I want to read.” It felt like not that many people were doing that kind of thing. I felt like I could write and draw well enough to tell the kinds of stories I wanted to tell, so it felt like this was something I could actually use my talents for. So it wasn't really scary at all. It just felt like something I could do with the talents I have, you know? It just fit.

A: Riffing on Clowes earlier, do you still feel like he's in your work? What did you take away from him?

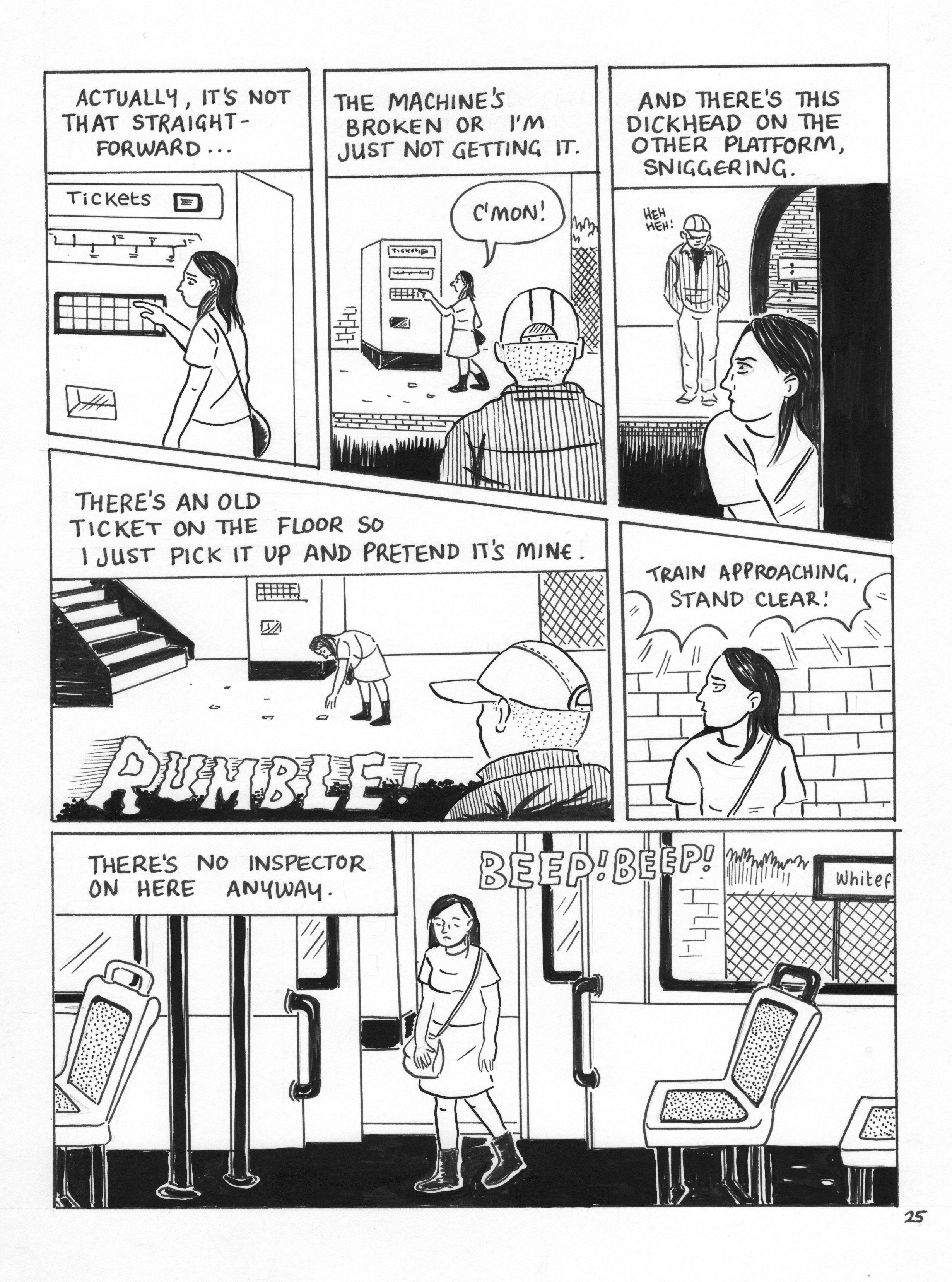

M: I realized early on that I'll never be able to draw like him, so I don't really even try anymore. I draw as well as I can and concisely as I can, but, you know, it's people like Gabrielle Bell and Laura Weinstein - who are actually in my generation, the same age as me - and discovering what they're doing ... they aren't really trying to be anyone else. They're comfortable with their own styles. That was really influential to me, and really kind of freeing, in a way.

When I first read Gabrielle's first book [When I'm Old and Other Stories] - you know the one I mean?

A: Yeah, I think I do. [He doesn't].

M: It's not polished at all, compared to like her current stuff, you know? But just seeing that, it's just like these stories are so great and have so much energy. They're just like her. That made me feel it's OK to stop drawing like other people. I mean, I'm a pretty wonky artist, I think, but there's certain things I feel I can do well. I can make characters act via their faces and show expressions.

You know, I'm still trying to get stronger and hone that craft, but yeah.

A: I feel like that's definitely a standout aspect of your work. Your characters are pretty well-defined, and if there's anything to latch onto, it's that. So, to ask you, making a character - like Iris [from The Sky in Stereo] or any other, what's something that character has to have?

M: I feel like you have to know their story, you know? Even if it ends up not matching. But just knowing the details of that person and their motivation. I mean, with Iris, she doesn't really know what she wants.

A: She seems to want to find the meaning in things.

M: Yeah, I mean Iris just wants to be loved. She's actually really lonely. I mean, she likes Glen, but it's kind of an awkward ... it's not even a relationship. I don't even know how to describe it, but ...

A: There's also that notion of transition, like she's in between things, whether it be youth and adulthood, or what not. Those sort of feelings ... is that something you're riffing on?

M: Totally, yeah. What happens to Iris kind of happened to me. You know, that search for meaning you mention - I'm currently penciling issue #3 right now - is kind of a huge motif in the book. She's like drifting into mental illness in that search for meaning, when there isn't actually meaning there.

A: It's anchored well, though, because you're very concise in your storytelling.

M: Well, I spend a lot of time writing. I over write, it seems, so that I can end up editing, so maybe it comes in the editing. I'm glad you think it came together because I work really hard on that aspect of it. But like I said, I studied literature in college; I read a lot of fiction. A good story totally is what makes me interested in a piece of work. That has to be there. Stylistic experiments are fine, if you have a lot of talent in a certain way, but for me, story is what I'm into. It's what I do best.

A: Do you feel there's a lot of the opposite going on right now in alternative comics?

M: Yeah, kind of. I mean, Fort Thunder was a big influence. We're talking like 9,10 years ago, and that influence has really had a strong hold. You see people come out of these comics courses and they're all very art-driven. Which is great. There are some very talented people out there. But, I don't know, that's just not me. A lot of my favorite writers aren't even in comics. People like John Updike. I'm way more into literary comics than I am art comics, let's just say that.

A: You don't seem very active on the "Comics Internet ™". Is that safe to assume?

M: Yeah (laughs). I've tweeted like once, which was a retweet, and I have a Facebook, but I'd rather spend time drawing comics or writing rather than spending time I don't have on the internet.

A: But if you had the time, would you want to?

M: Computers are boring, aren't they? (laughs). Yeah .. uh .. eh. Maybe I'll try to update my blog more in the next year, but it just seems like a chore, you know? It's a time drain. I'm kind of lucky, you know, to have grown up before the internet. Who knows what kind of mess there could have been if all my dark moments had been public. That would have been awful.

But yeah, I feel like I have to focus my time doing the actual work. Plus like, having a kid ... do you have kids, Alec?

A: I'm 21 years old, so no.

M: OK, OK, well you'll find out. You're free time shrinks to nothing and when you do have it, all you'll want to do is drink a beer and watch something.

So, I don't know, it's just priorities at this point.

A: To wrap this up, in the grand scheme of alternative comics, how has the work itself changed from the time you got in to now?

M: Like in a general sense?

A: Yeah.

M: It's way better than it used to be, I think. There's just so many more people interested in publishing comics despite the conversation of publishing being a dying industry. There's stuff that didn't exist 15 years ago that does now. I mean, you can study comics in college. That's amazing to me. When I was trying to figure out how to make a comic book, I searched for anything I could lay my hands on ... like Will Eisner's Comics and Sequential Art book, or whatever it's called. Just to get tips from it. Now it seems there's classes you can go to.

I mean, there still seems to be a big lo-fi bent. I like Chuck Forsman's The End of the Fucking World, and I love his girlfriend's, Melissa Mendes', book Lou. It feels like people are being more deliberately lo-fi now, which I always liked that stuff., so I guess I can just indulge more in what I like, since there seems to be so much of it.

The Exit

Go buy The Sky in Stereo from Yam Books. Here

Alec Berry will become a better interviewer one day. Follow him on Twitter @Alec_Berry.