In THE LIGHTBOX, a four-part series running all week, CBR speaks with some of comics' biggest, most distinctive artists about their process and how they approach art and design in their work.

John Romita, Jr. has had a long run as one of Marvel Comics' major modern creative talents with an expansive resume, including Marvel mainstays like "Iron Man," "Daredevil," "Amazing Spider-Man," "Daredevil," "Avengers," "Captain America" and many more. Romita is also known for co-creating "Kick-Ass" with Mark Millar, the third volume of which concludes this year, and will debut a new "Superman" ongoing series with Geoff Johns at DC Comics this summer.

RELATED: THE LIGHTBOX: Brian Stelfreeze on the Uniqueness of "Day Men," Timelessness of Batman's Design

In his LIGHTBOX interview, Romita spoke about artistic lessons learned from his father (legendary comics artist and longtime Marvel art director John Romita), shares stories about the design of Dazzler and recalls advice from his first years as a Marvel artist that he still uses today. Plus, he discusses creative process with writers and some of the most well-designed comic book characters.

CBR News: How has your perspective on comics evolved over the years you've been in the industry?

John Romita, Jr.: When I first started, it was all about making a living. I was just trying to work as hard as I could to pay my bills, which led to a good work ethic. That altered as I realized I had to be more in control of it. Suddenly it wasn't just page rate, it was sales on the work you did. That made me a little more earnest in my attempts and more ambitious. On any job, you're in it to make a good living. So that's changed with me over the years. I've been able to see what can be done to control success. I haven't always been successful with that.

As far as designing characters or coming up with stories, it's a little bit difficult to gauge that unless you include the writers. Whenever I design something, regardless of its success, there's been a writer that comes up with the name. I've created my own characters -- Shotgun, Blackheart, Jimmy Six and a couple other minor characters because I added them. I get a name from a writer and some information of what they have in mind but generally they don't necessarily have something in mind, per se. They have a name and say we're going to do this with the story and I can design it as I see fit, which is fun.

Typhoid Mary with Ann Nocenti was pretty self-explanatory. The Hobgoblin was just a complete rip-off of the Green Goblin. I have no shame in saying that. But when character names have been dropped on me, for a visual I go right to fashion magazines and clothing designs because I want to see what's in vogue fashion wise. I'll go to an extreme fashion magazine called "W," which is a real cutting edge fashion magazine within the industry. There's some really wild fashions in that. I look at some outrageous fashions and see if I can come up with something that would be fashion-centric, relatively popular and then try to go with something relatively superhero-ish.

I get the feeling that whenever female characters are created, it's boobs and butts and a lot of revealing costumes that aren't necessarily flattering. Not every female character has to be a pin-up body and so on. I'm more conscious of reality as far as that goes, but for costumes I go to fashion and then I go to function. It's pretty much the same thing with the male characters. I don't want to do a lock-step skintight costume unless it's called for with the writer specifically saying, do this. The most recent design I had which was a skintight costume was Jet in the "Captain America" series with Rick Remender. He said, "Knock yourself out with the character designs," so I played with it a little bit. There were shoulder pads that were along the lines of armor. I fashioned it a little bit after Sif, a Jack Kirby character from "Thor." I also rummaged through some Kirby, Romita and Buscema characters from way back when that I really enjoyed.

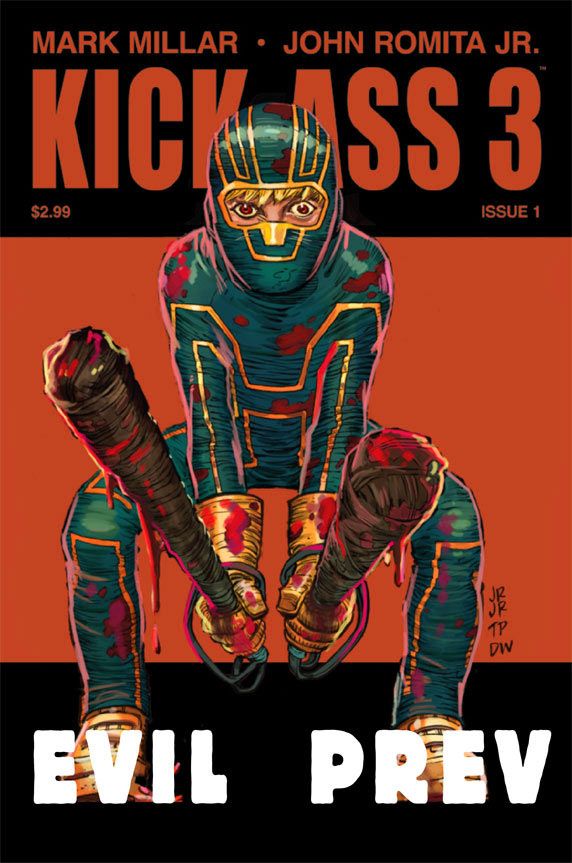

Nothing I do is so amazingly original. It's derivative in some respect, either from fashion or previous characters as far as the flavor goes. With "Kick-Ass," I had to be reminded in my own mind that these are amateurs and their costumes should look it -- so, no muscles, no tight costumes. I remember the first issue came out and somebody wrote in, "Romita draws too many wrinkled costumes." That was one of the first critiques. I wanted to scream at the top of my lungs, do you know any amateurish costumes that are perfectly skin tight? There would be a lot of wrinkles in them. With "Kick-Ass" I was constantly being reminded with a big sign over my desk, "These are real people who have amateur taste in costumes." That's where that look comes from. The names of the characters come from Mark Millar's twisted imagination. Then we just combined our twisted imaginations and e-mailed back and forth. That's it. There isn't any great master plan. I kind of wing it and go as my mind reacts to the first name or the first discussion with the writer. There's usually something that will pop into my head as soon I have a discussion with the writer.

RELATED: Johns & Romita "Really Want To Create Something Big" With Superman

In "Kick-Ass," you were designing non-superpowered people with a handmade look and those characters make an attempt to imitate the designs you might create in a Marvel series.

Right. Or, in the case of Big Daddy, for the film he had this Batman fetish, so to speak. If you're a twisted individual the first thing that might come to mind is a Batman costume. I threw a lock on Hit Girl's cape because I wanted that lock to mean a couple things. One is so the cape couldn't get pulled off -- which is silly because she could get choked by it. But the lock meant strength to me and for a little girl, that's what I was thinking of. Interestingly, that was not in the film but I just remember thinking to myself, "What would she do to keep the cape on her? A padlock for strength to give you security." That's along the lines of a "Kick-Ass" character. That's a functionality that may or not be in superheroes but was in "Kick-Ass."

In a strictly practical sense, the lock doesn't work, but it's a good design, it works symbolically. Is that kind of symbolism and design important when designing a character of any sort of at some point stepping back and saying, this isn't strictly practical but it works symbolically and on other levels?

Absolutely.

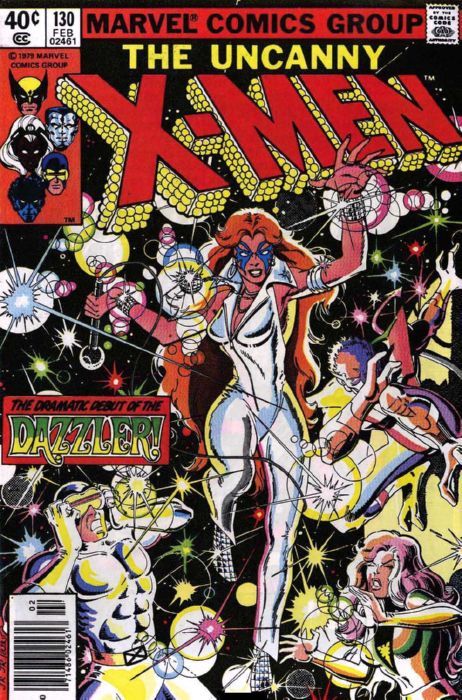

I know you helped design Dazzler --

What a segue. [Laughs] They asked me to pick something that would be fashionable. There's a perfect example of what I was talking about, something fashionable that could also be a superhero costume. Back at the time, going to nightclubs, women were wearing clothes that left nothing to the imagination. Skintight outfits -- it was easy enough to draw and design a costume or a character like that ... roller skates and skin tight outfits and makeup.

So while for people my age her costume may just seem like another fantastic superhero outfit, you're saying that's not true.

It is now, but back then it was taken from an outfit I'd seen a couple of times. There was nothing about that character and the design that was otherworldly at all -- except maybe the face painting, but face painting was done all the time. You have to remember this was nightclubs 24/7. They were called discotheques. Women were dressed in skintight everything and body suits and people were roller skating everywhere. I remember making notes in my head when I would go to clubs and see women in costumes. There was nothing about that character's design that was out of the imagination.

In your recent "Captain America" run with Rick Remender, you got to design new characters, but in your more recent bigger projects -- like "World War Hulk" or "Avengers" -- there aren't as many possibilities to design, make new characters, and experiment.

When you have that many characters, the propensity is not to come up with a new group of characters. You already have a group. You generally don't create anything. That was difficult just for the amount of work, but in a design sense when you have that many characters for functionality it supersedes design. Let's get everybody in this panel. That's part of the job. You're less involved in coming up with a new villain when that villain is based on the conflict between new groups. You have villains involved like Magneto and Ultron, but you're more involved in designing mass battles because there were so many conflicts.

It sounds like group books aren't just more work and require drawing more lines, but they require you to think differently.

Absolutely. You have no choice but to think differently. If it's a single character with a couple of bad guys and even if it's Fantastic Four, there're four characters and if there's one villain, that's five characters -- as opposed to having 45 characters. There were pin-ups and double page spreads in "X-Men"/"Avengers" that took me days to do. I was attempting designs, but it was nearly impossible. It looked more like a thousand piece jigsaw puzzle which will function occasionally to get everybody in for that purpose only, but design is out the window. George Perez will say the same thing. Sometimes you lose your design sense because you're trying to get it all in. More than a few times, I've been asked to draw casts of thousands and it's not easy. It's fun, but it's not easy.

What do you look for in a writer or in a collaborator?

I'll leave the creator-owned stuff aside for a moment. If I'm doing superhero comics, I want to do something I haven't done before and come up with something I haven't done before. That's difficult. It's the same mindset I have when I'm designing a cover or drawing the interiors, I'm trying to do something that's different -- which is nearly impossible. I've been doing it long enough that I'm sure I've repeated shots a million times. Not only that, but I started after the greats had already existed for generations. Nothing I've done is so amazing it hasn't been done before. You're intimidated by that -- trying to do something different. I want to do a story that's different. Writers are probably struggling with the same thing, coming up with something different. It's like writing a song or writing a book or coming up with a new magazine design. It's been done a trillion times before. Coming up with something new is difficult, but it doesn't mean it shouldn't be on your mind first and foremost. The first thing I want to do is something different -- not necessarily a brand new character but a new take on an old character. I will do Spider-Man under any circumstances. I have this leaning towards Spider-Man that just supersedes anything else. I think he's the best character ever created. So I'll do it even if it's not different but setting him aside, I try to do something with a character that I've never done before. I haven't done Doctor Strange before monthly. I haven't done Fantastic Four monthly, although I've done the characters a couple of times in large super books.

Which leads me to creator-owned: the four or five projects I've come up with myself I came up with ideas that were based on instances that I've been through in my life or witnessed or had read about that affected my life and I came up with something super or supernatural to attach to it. My father had me watch movies with him. There was no such thing as DVR or cable when I was a kid. If it rained during the summer, we were stuck inside watching movies and my father's taste in movies was legend. He would force us -- although eventually we didn't have to be forced -- to watch movies with him. The greatest movies ever made: "On the Waterfront," "12 Angry Men," "Inherit the Wind"; fantasy films like "The Devil and Daniel Webster."

I always want to combine reality with fantasy and the right balance between the two of them. It goes back to Stan Lee's way of looking at things. Neil Gaiman is brilliant at that where he combines reality and fantasy just the right amount of each. Stan Lee said if you don't have Peter Parker as Spider-Man you're going to have a boring twenty-two pages of a guy in a costume so you have to balance the two.

You mentioned your father, who was a great artist but he was also the art director at Marvel and designed many characters. What did you learn from him about design?

The design advice I got from my father was more by example -- like storytelling. I would watch, listen and learn. He never wanted me to feel as though I had to do what he was doing. He didn't want me to feel compelled because of him. If I had questions, he would answer my questions. If I asked him for advice on something, he would answer, but he never volunteered anything. Especially after I had a chance to work at Marvel when I was very young. He went out of his way to say to them, do not give him any breaks just because he's my son -- as a matter of fact, be tougher on him because I want there to be no doubt that he can handle it. If he can't handle it, so be it. If can handle it, he will get through it and be better for it. I was forced to be a better artist because I had to work harder at it. Marie Severin was very tough on me, but she was great at the same time. The same way my father would have been -- though maybe not as tough as my father would have been, probably. Do it and if it's good enough, we'll take it. If it's not, sorry, kid.

The design and storytelling sense came from just hanging out with my father, watching movies with him, discussing things with him, watching him draw Spider-Man and Daredevil while working with Stan. The storytelling, that way of doing things got reinforced as I started working on it because I wasn't that good an artist. I was lousy, but I could tell a story. Jim Shooter added his two cents in by saying to everyone who worked at Marvel at the time, "I want you to over-tell stories. I want you to be over-deliberate."

It ended up being a blessing in disguise because it taught every one of us how to tell a story -- although not everybody stuck with deliberate storytelling. The storytelling developed first. A lot of guys say that's more difficult than the art, but to me it was not. I was a better storyteller than an artist. To this day I probably still am that way. To me, my art is average; my storytelling is better than average. My storytelling makes my artwork look better. I call it sleight of hand. The prestidigitator wiggles his fingers in front of your eyes while at the same time picking your pocket with the right hand. That to me is what storytelling does for my lack of quality in art skills. Again, that's all subjective, though I do think the storytelling makes my art look better. It allows me to design things that most people wouldn't and it makes me a better artist for it.

RELATED: "Kick-Ass" Co-Creator John Romita Jr. Faces Undecided Future

What do you mean exactly by "over-tell the story?"

That means establish, establish, establish. Every couple of pages, you should establish where you are. The tendency towards doing a fight scene is you have five pages and you don't know who's where. His point was -- and this is an excellent point -- every couple of pages, if not every couple of panels, you should re-establish where you are. Even as far as pull back on the fight and show where they are. ... My way of looking at it is always make sure the panels are connected in some form even if you're choreographing a fight. I connect them in some way or form. The storytelling "must" from Jim Shooter was "establish." That doesn't mean I have to pull back and show tiny little figures on this map, but I can connect it to the previous establishing shot. There might be some landmark and I can use that. I have all these different tools in my kit, so to speak, that go back to Jim Shooter. He said, "Establish, establish, establish, I want to know where everything is."

All it did was combine it with what I learned from my father, but didn't quite understand. When I was working on the job and I had to be told establish more, it finally happened. The design sense I got from watching my father draw and then going to school. The dynamic anatomy and design of superhero books all coalesced because it played into the visual design I had learned -- it was just a matter of combining them. Design sense applies to superhero books just like it would a photograph of a still life.

When you're working with writers -- whether it's Mark Millar on "Kick-Ass" or Rick Remender on "Captain America" -- what's your approach to the collaborative process?

The way it's worked out really well is a hybrid of a plot and a script. Fortunately -- or unfortunately -- I've become older than all the writers I work with. [Laughs] I don't know how that happened. My experience with storytelling allows the writer to feel more comfortable. They don't have to explain everything in detail. I tell the writer, "If there's anything I intend to do that's going to change in any way what you've given me, I will call you and discuss it with you." I generally will not take anything out. I'll add something like a panel or two or move things around so I can pace it different than the writer. I don't think I've ever made a writer add dialogue to explain anything. What I've done more than a few times is change the pacing a little bit, but I'm not going to take away from the editorial content of the writer. That's insane. I'm working with these guys because they're brilliant and I want the best they have to make the product the best. I tell them from the beginning, if I do anything different from what you had in mind, we're going to discuss it. It works out really nice. It worked with Millar, worked with Rick, worked with John Byrne. All of these brilliant writers who accepted it and when they sent me a script/plot, it worked out nicely. I could tell the story well enough that they don't have to explain things so deliberately or precisely as they would to a younger artist where they're not familiar with their style. Which is a great compliment. When Neil Gaiman told me, "You do what you do best and I'll adjust on the fly," that was the greatest compliment I think I've ever gotten.

When you started out, Marvel-style scripts were more common, but now pretty much everyone is using full script.

Yes, but even with the scripts, there are moments where the writer needs help and that's where the artist comes in. The majority of the work comes from the art. That's where the design and pacing comes from. If you're working with a young artist who's inexperienced then write in more detail, but the writers I work with know going in that I don't need that. They can feel a little more comfortable to say, okay, this battle will happen here, you have three pages. That, to me, is the ultimate pleasure as an artist. I remember John Byrne's first plot on "Iron Man" back in the '90s. I think it was two pages. He was so open to letting me to do whatever I wanted. I smiled at the compliment of it and because it was so much fun to work on. And then he put my name first in the credits. That's why I'll always be a fan of John Byrne. John Byrne was an artist first and working with him was a true pleasure. He's a great guy, a friend, a brilliant talent, but that was the most fun I'd had. When he sent me that plot and at the end said, "Knock yourself out." Some form of that process has played out over the years. That's a compliment when the writer will allow me to do what they want and they'll change on the fly, but I won't make them change anything.

Name a comic or a character that you think is well designed.

Great design visually? I love Daredevil. I love Punisher. There's something simplistic about it, but it's the same effect that Batman has on artists. That silhouette that looks so cool. Punisher and the skull design is iconic. Daredevil with the horns. Batman with the cowl and cape. Those kind of things make it fun. They're established characters, they're iconic characters, you can play with silhouettes and shadows and design. The all have facial expressions -- Daredevil's half face, Batman's half face. When characters' faces are covered by masks it hard to get emotion out of them.

I love the visuals of Daredevil. The best character I've ever done is Spider-Man, but my favorite character to draw is probably Daredevil.

You're working on a big superhero project -- "Superman" -- but you're also working on a creator-owned project with Howard Chaykin, "Shmuggy and Bimbo."

I'm hoping it's going to come out in 2015. I'll be working on it in 2014. Howard's gotten me the first script. It's fantastic. I came up with a treatment, pitched it to Howard over coffee in Manhattan, gave him all the notes and he came up with a beautiful version of his own. It's wonderful. I have a lawyer named Harris Miller who has represented and does represent Howard Chaykin and I told him I had this great idea and he said, "Well, Howard Chaykin would love this." It was as simple as that. The combination of the two of us should be interesting. I'm proud of the idea but I am so proud of the end result that Howard has thrown his more than two cents into.

So, you had a sense of the characters and the approach from the beginning?

They're based on these two real characters. I had done some model sheets of them and some other characters. They're based on characters I know and see. The way I'm going to draw is something different than I've done before. "Kick-Ass" was pencilled differently than I had done superhero books and now I'm going to do something different with "Shmuggy and Bimbo." It's going to be all in pencils, charcoal pencils and soft leads. It's going to be in black and white. I'm very excited about it.

John Romita Jr.'s next big superhero project, "Superman" with Geoff Johns, hits stores this summer.