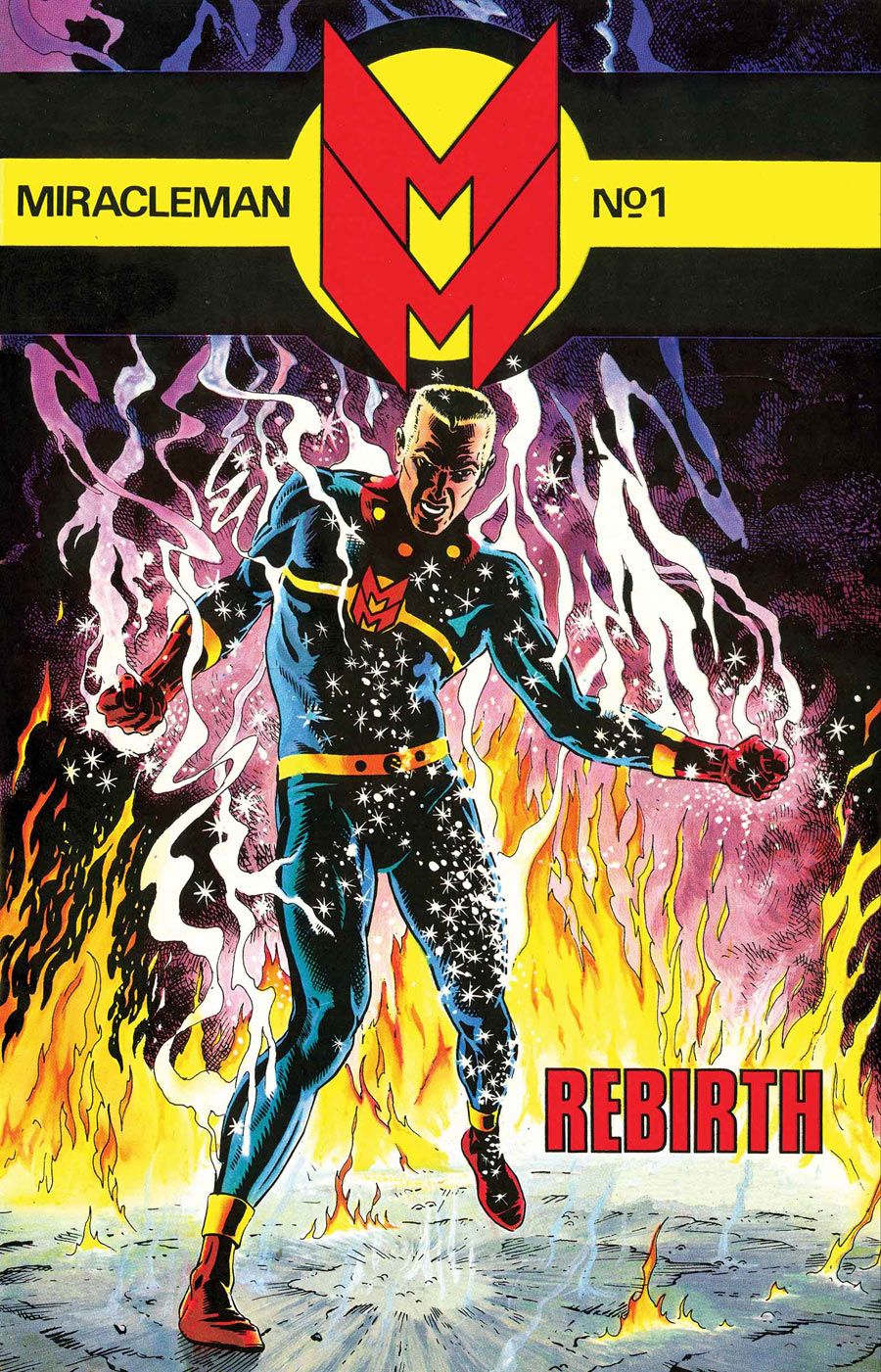

Marvel on Tuesday released the first preview of its remastered Miracleman #1, dividing fans with its modern coloring. Some of the comments come from newer comics readers still wondering what the big deal is about this series; surely, the "mehs" are already being prepared for the issue's Jan. 15. debut.

Despite the updated coloring, it probably isn't fair or even realistic to hold the series up against contemporary comics, despite Miracleman's significant influence on a good deal of them. Instead, it's best to view these stories in the context of the times, which makes it easier to see why Miracleman (or Marvelman, if you prefer) is the natural stepping stone to Watchmen, and established many of the themes Alan Moore and many creators that followed him would explore in subsequent works up through the present day.

Among the relatively few fans who have read these stories, Miracleman is often held in the same regard as seminal works like Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns. Both of those revered miniseries debuted in 1986 and caused a seismic shift in how superhero comics, and mainstream comics in general, were created and received. It's worth noting then that a good amount of what Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns later touched upon and accomplished had been done four years earlier with Marvelman. If it weren't for the legendary rights quagmire that prevented those stories from being reprinted, Miracleman would almost surely be just as celebrated and commercially successful as its successors.

The character, then called Marvelman, was created in 1953 by Mick Anglo to replace the original Captain Marvel, whose title was discontinued because of DC Comics' famous lawsuit against Fawcett Comics. The U.K. reprints were popular, so to try to hold on to that readership, L. Miller & Son asked Anglo to come up with a replacement for the superhero. For about 10 years, Anglo successfully riffed on the classic Captain Marvel style with his own fun Marvelman stories and created his own universe.

Flash forward about 20 years, when publisher Dez Skinn wished to reprint the classic Marvelman stories. To build interest, he decided to release new stories for then-modern audiences. As a former Marvel UK editor, Skinn went through his contacts to find the right creators for his new publishing company Quality Communications, and its indie comics anthology Warrior. Enter artist Garry Leach, art director at Quality, who recommended newcomer Alan Moore, who had mostly worked on standalone stories for Doctor Who Magazine and 2000AD. Moore and Leach's version of Marvelman debuted in 1982 in the black-and-white Warrior #1, which also included the first installment of Moore and David Lloyd's V for Vendetta. The magazine had limited distribution outside of the United Kingdom, which helped add to the mystique of Marvelman for North American superhero fans right from the start, building anticipation when Eclipse published a colorized version renamed Miracleman starting in 1985.

Moore's radical reworking of the character's origin and the world in which he existed was a surprising disconnect from the character's sunshiny Golden Age past. We soon discover there's a reason only Marvelman remembers his comic book origins, as Moore's stories zoom out and reveal a new reality. Although the term "retcon" often has a negative connotation, in Moore's adept hands, it becomes a revelation, opening up the character to new stories (American readers first experienced that with Moore's classic Saga of the Swamp Thing #21 in 1984).

Transforming a character is something Moore excels in. Like a blues or folk musician from the 1930s, he borrows and mixes lyrics and melodies, which evolve to create something new. From taking an historical-fiction version of Jack the Ripper for his and Eddie Campbell's From Hell to the Charlton Comics heroes becoming the cast of Watchmen to the pulp and literary sources that informed The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen with Kevin O'Neill, Moore loves to take familiar diamonds and shift them in the light, revealing new surfaces. Few find as many nuances, but his success in doing this indirectly freed up a lot of creators to inject new life into tired properties. Frank Miller brought forward the pulp noir aspects of Batman in The Dark Knight Returns and Batman: Year One. Green Lantern was saved from his villain legacy by Geoff Johns and Ethan van Sciver in Green Lantern: Rebirth. Spider-Man returned to basics in "Brand New Day." There are countless others. He wasn't the first to bring a character back, but the way he handled it was much more progressive than any before, demonstrating that readers could handle big changes to the core of the character if the story was good enough.

These Miracleman stories also initiated the deconstruction of the superhero genre. Miracleman's wife continually calls out the absurdity of superhero conventions. She's the voice of the real world, and the story teeters on whether the real world will give in to the fantasy or if fantasy will give in to the real world. How many promotional blurbs for superhero comics have you read that start with some variation on "What if superheroes were real?" -- usually followed with an explanation that this one will really blow your mind. From Mark Millar's Kick Ass to Mark Millar's Wanted to every other new superhero property over the past few decades, they've tried to find a new angle on Moore's theme. Miracleman's powers are explained as some version of telekinesis instead of super-strength and flight, something that would be used again by John Byrne for his 1986 reboot of Superman.

The real world also intrudes with the result of property damage, injury and death caused by fantastic superhero battles. That really was a massive shift in 1982. Superheroes always saved everyone; even if there was property damage, buildings were empty, everyone gets out of the way in time, and all is OK at the end of the day. More times than not, bystanders were played for comedic effect or to provide exposition. Miracleman's attempts to save people were resulting in broken bones. The laws of physics from his comic book origins weren't working in the"'real world": London was burned to the ground; an epic superhero slugfest was actually a disaster. Future stories picked up on this concept, probably most significantly in Warren Ellis and Bryan Hitch's The Authority, and last year's Man of Steel film, but instead of Moore's ironic ineffectiveness of superheroes, they usually got caught up in the spectacle and bombast of the action. Moore's use of superheroes to point out the silliness and ineffectiveness of superheroes is probably one of the themes most frequently missed by those influenced by his work. From creating more damage to botched attempts at controlling the world to save it, this motif most famously appears again in Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen. Between those two works, Mark Gruenwald's Squadron Supreme mini-series also explored this, as did Mark Waid and Alex Ross' Kingdom Come and, again, The Authority.

Despite Moore's cynical message about superheroes, he and artists Leach and, later, Alan Davis, choreographed some amazing fight scenes, despite the startling violence. While there had been some classic battles in the past, this raised the bar considerably. I can't help but think that the climactic battle in the famous "Death of Superman" story was inspired by some of the fight scenes in Miracleman. Once the Eclipse series reached the end of Moore's run, Neil Gaiman took over the series. In the final issue published, the fight scene illustrated by Mark Buckingham was later heavily referenced in The Matrix Revolutions.

Miracleman was also known for containing controversial elements. Most frequently this was in the form of brutal violence, but this was also the first use of rape in a Moore comic; there's also an explicit depiction of birth. These kinds of no-holds-barred visualizations were mostly unheard of in mainstream comics of the time, and Moore's use suggested it could be done to serve the story. Legions of comics have tried to use increasingly explicit depictions of sex, violence and gore throughout the '90s to now for better or worse.

Most comics in the early '80s were still pretty bright, happy and somewhat simplistic. Miracleman quickly showed they could be different. As with Watchmen, the example proved to be a template that produced flawed duplicates but that doesn't take away how different it really was for the time. Come January, we'll see if it holds up to a modern reading after 30 years. But even if it doesn't, it deserves its place alongside the major superhero canon.